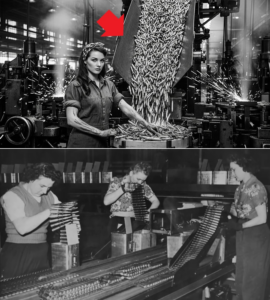

The Factory Girl Who Rewired a War in One Quiet Shift: Her Small Process Fix Tripled Ammunition Output and Kept Entire Offensives From Stalling

The idea arrived the way most important ideas do: not with a speech, but with a problem that refused to go away.

Evelyn Hart was nineteen—too young, she sometimes thought, to be trusted with anything that could change the shape of a war. But the war did not ask permission from birthdays. It simply took what it needed and gave you a uniform made of grease-stained overalls.

Her factory badge said E. HART in black letters that had begun to rub away, as if even ink was exhausted. The badge hung from her collarbone like a small claim to identity, though inside the plant people weren’t really names. They were stations. They were quotas. They were hands moving in rhythm.

The plant sat on the edge of a river city that still tried to pretend it was ordinary. Outside its gates, you could buy bread if you arrived early. You could hear music if you stood near the right window. You could see boys in uniforms on leave pretending they weren’t afraid.

Inside the gates, the factory breathed in metal and breathed out numbers.

Thousands of shells. Thousands of casings. Thousands of primer cups and fuses and stamped parts that looked meaningless until you remembered each one could become a day of survival for someone you would never meet.

Evelyn worked on Line 3, finishing and inspection—an awkward corner of the process where speed and accuracy fought each other every hour. Her job was to check cartridge cases for defects, toss the bad ones, stamp the good ones, and feed them onward like a link in a chain that never stopped moving.

She didn’t mind the repetition. Repetition had a strange comfort to it. It made time pass in predictable pieces. It made the war feel… containable.

What she minded was waste.

Waste was a sound. It was the clatter of a case dropped wrong. It was the hiss of compressed air used to clear a jam. It was the shouted curse when a bin overflowed because upstream ran faster than downstream. Waste was the look on the foreman’s face when the numbers came in and the numbers were not enough.

The first time Evelyn heard the word offensive inside a factory, it felt wrong, like hearing battlefield language in a place that smelled of oil and soap.

But it happened often.

The supervisors didn’t talk about politics. They talked about schedules. They talked about supply trains. They talked about how “the push” in some distant place depended on what came off their floor.

When the plant missed its quota, the blame moved downhill like water. It landed on foremen, on shift bosses, on line workers. It landed on girls like Evelyn, who came home with metal dust in their hair and slept with their hands still curled as if holding a tool.

On a Tuesday morning that felt like every other Tuesday, the line jammed at 09:17.

It wasn’t dramatic. A conveyor slowed. A bin filled too quickly. A batch of cases arrived with slightly warped rims, just enough that the feeder mechanism caught them wrong. The entire station’s rhythm broke, and once rhythm broke, everything became noise.

Foreman Draper appeared behind Evelyn like a weather change. Draper was in his forties, hair slicked back, jaw always tight. He wore a tie even on the floor, as if formality could intimidate the machines into behaving.

“What happened?” Draper barked.

A mechanic knelt near the feeder, fingers black with grease. “Bad batch. We’ll clear it.”

“How long?” Draper snapped.

“Ten minutes,” the mechanic said. “Maybe more.”

Draper’s face tightened like a fist. “We don’t have ten minutes.”

Evelyn watched the jam with narrowed eyes. She didn’t say anything. Girls didn’t interrupt foremen. Girls didn’t offer opinions on machinery. Girls did what they were told and tried not to slow the line.

But Evelyn had been watching the line for months. She had learned its little moods. She had learned that jams weren’t random—they were predictable, if you cared enough to notice.

And she had noticed.

The warped rims came from the press station upstream, where a new operator had been moved in last week. The press dies were wearing unevenly. The inspector before Evelyn had been missing the early warning signs because the cases still “looked fine” until they hit the feeder at speed.

Evelyn felt something tighten in her chest—the same feeling she got when she saw a pot about to boil over and nobody was watching it.

Draper stormed away to shout at someone else.

The mechanic kept working.

The conveyor sat idle, a silent insult to quota.

Evelyn turned to the girl beside her—Martha, older, with tired eyes and a habit of humming quietly when she worked.

“Watch my station,” Evelyn whispered.

Martha frowned. “Evelyn, don’t—”

Evelyn was already moving.

She walked upstream, past the inspection table, past the stamping station, toward the press area where the noise was louder and the men were more concentrated.

The press was a beast: a tall steel frame that slammed down with the steady anger of a giant’s fist. The operator—a young man named Cole—worked it with the tense focus of someone still learning.

Evelyn stood just outside his space, waiting until the press cycle ended.

Cole looked up, surprised. “You lost?”

Evelyn kept her voice calm. “Your rims are drifting.”

Cole blinked. “My what?”

“The lip,” Evelyn said. “They’re warping. Not all of them. But enough.”

Cole frowned, defensive. “They passed check.”

Evelyn pointed to the output tray. “At this speed, they look fine. But the feeder downstream catches them. It jams.”

Cole’s cheeks reddened. “So what, you’re blaming me?”

Evelyn shook her head. “No. I’m blaming the die. The wear is uneven. If you adjust the guide and change the inspection point, we catch it earlier.”

Cole stared at her like she’d spoken a foreign language.

A senior mechanic wandered over, drawn by the conversation. His name tag read S. LEWIS. He was older, hands scarred in the way only machinists’ hands became.

“What’s this?” Lewis asked.

Evelyn pointed again, more confidently now that an adult with authority had arrived.

“The die’s wearing on one side,” she said. “The cases wobble on exit. The inspector downstream only checks random samples, and the random ones aren’t catching it. Then we get a jam where it hurts most.”

Lewis picked up a case, ran a thumb around its rim. His eyes narrowed.

“Huh,” he said.

Cole opened his mouth to protest, but Lewis raised a hand.

Lewis walked to the die housing, crouched, inspected the alignment marks. Then he exhaled.

“She’s not wrong,” Lewis said.

Cole’s face went pale. “I— I didn’t—”

Lewis shook his head. “Not your fault. The die should’ve been rotated yesterday. And we should’ve had a gauge check at the exit.”

Evelyn felt a flicker of relief. Not pride. Relief. Because she hadn’t just imagined it.

Lewis stood and looked at Evelyn. “You notice this often?”

Evelyn hesitated. “I notice jams before they happen,” she admitted. “Usually.”

Lewis grunted. “We all should.”

He called for a die rotation and a quick alignment adjustment. It took six minutes, not ten. When the press restarted, the output looked steadier.

But Evelyn knew that fixing one die wasn’t the real solution.

The real problem was the system that let the drift travel downstream until it became a crisis.

She went back to her station and found Draper waiting, face stormy.

“What do you think you’re doing?” Draper hissed.

Evelyn’s throat tightened, but she held his gaze.

“Preventing the next jam,” she said.

Draper’s eyes widened slightly—more surprise than anger now. “You don’t have authority—”

“I know,” Evelyn said quickly. “But the jam was from the press drift. If we add a simple rim gauge check right at the press exit, we catch it there. And if we change the bin flow so the feeder never floods, the line won’t choke when one batch is slightly off.”

Draper stared at her like she’d grown a second head.

Martha, listening nearby, stopped humming.

Draper’s voice was tight. “You want to redesign the line?”

Evelyn shook her head. “Not redesign. Just… move the check and change the handoff.”

Draper exhaled through his nose. “You know what happens when we slow the press for checks?”

Evelyn answered before fear could stop her. “We lose seconds there and save minutes here. Minutes every day. Hours every week.”

Draper’s jaw worked. He looked at the stalled conveyor, at the accumulating bins, at the men pushing to restart.

Then, unexpectedly, he said, “Show me.”

Evelyn’s heart jumped.

She didn’t smile. Smiling felt dangerous. She simply nodded and began explaining what she’d been thinking for weeks but had never dared to say aloud.

The feeder jam happened because cases arrived in uneven pulses—floods and gaps. The inspection downstream was too late. The press output needed a simple go/no-go gauge at the point where the drift began, not where it became visible. The bins needed a controlled buffer, not an open pile. They needed a “flow limiter” and a visual signal that told operators upstream when the downstream station was nearing overload.

Simple changes.

Cheap changes.

The kind of changes that didn’t require new machines—only a new habit.

Draper listened, skeptical but not dismissive now. He asked questions. Evelyn answered, using the language she’d learned on the floor rather than the language she’d learned in school.

By lunchtime, Lewis and another mechanic were building a crude rim gauge out of scrap and a micrometer setting. They installed it at the press exit. Cole was taught to test every tenth case at speed, and to halt for a quick adjustment when the gauge began to fail.

They also changed the bin handoff. Instead of dumping cases into an open overflow that flooded the feeder, they added a simple gated chute—gravity-fed, narrow enough to limit surges—so the flow stayed steady.

It looked almost silly. A piece of metal and a hinged flap. Nothing glamorous. Nothing “strategic.”

But when the line restarted, it ran differently.

It ran like it could breathe.

By the end of the shift, Line 3 had exceeded quota for the first time in two weeks.

Draper didn’t congratulate Evelyn. Foremen didn’t do that. He simply stared at the numbers on the clipboard as if they were suspicious.

“Do it again tomorrow,” he said.

Evelyn nodded. “We will.”

The next day, they did do it again.

And the next.

The jam count dropped sharply. The rework pile shrank. The mechanics spent less time sprinting to crises and more time preventing them. The operators began trusting the gauge like a weather sign—when it drifted, they corrected before the storm.

Word spread the way useful gossip always did: quietly, from station to station, carried by tired mouths in break rooms.

“Line 3’s running clean.”

“Draper finally fixed his bottleneck.”

“You hear it was one of the girls who saw it?”

Evelyn pretended not to hear. Pretending was safer.

But the plant manager heard.

Two weeks later, Evelyn was called to the office upstairs—an office that smelled of paper and polished wood, far from the honest stink of oil.

The manager, Mr. Whitaker, was a careful man with careful glasses. He gestured for her to sit, then slid a folder toward her.

“I’ve been reading reports,” Whitaker said.

Evelyn’s stomach tightened. Reports could mean praise or punishment. Both were dangerous in wartime, because attention was a kind of spotlight.

Whitaker tapped the folder. “Line 3 output is up,” he said. “Scrap is down. Mechanical downtime is down. Explain.”

Evelyn swallowed. “We moved the inspection point,” she said. “And we regulated the bin flow so the feeder doesn’t choke.”

Whitaker blinked, as if expecting a more complicated answer. “That’s it?”

Evelyn nodded. “That’s it.”

Whitaker leaned back. “Do you understand what that means?”

Evelyn hesitated. “It means fewer jams.”

Whitaker’s mouth twitched. “It means more than that.”

He opened a sheet of paper and turned it so Evelyn could see. It showed numbers, tallies, comparisons. Output per shift. Output per week.

“Your line’s output is nearly triple what it was during the worst days,” he said quietly. “Not because we bought new machines. Because we changed where we caught the error and how we moved the work.”

Evelyn stared at the numbers, feeling something strange and weighty rise in her chest.

Triple.

Whitaker continued, voice low. “There are men overseas who will never know your name,” he said. “But they will feel the difference. When their units don’t pause because ammo didn’t arrive. When their commanders don’t delay because supplies are thin.”

Evelyn’s throat tightened. “I… I just didn’t like the waste.”

Whitaker nodded slowly. “Waste is the enemy we can actually reach.”

He slid another paper toward her. “We want to replicate your changes on Lines 1 and 2,” he said. “And possibly at the sister plant downriver.”

Evelyn’s heart thudded. “Me?”

Whitaker’s eyes were sharp. “Yes,” he said. “You know what the problem looks like before it becomes a disaster.”

Evelyn felt suddenly dizzy. Not from pride, but from the terrifying thought of being responsible at scale.

“I’m not an engineer,” she whispered.

Whitaker’s tone softened. “No,” he agreed. “You’re something more dangerous: you’re someone who watches the system.”

The real test came a month later, when the factory received an urgent order stamped with red ink.

An upcoming operation—a “push,” as the supervisors called it—required increased ammunition shipments on a schedule that didn’t care about excuses.

The plant shifted into a higher gear. Overtime became normal. Meals were eaten in corners. People learned to sleep in fragments. The city’s lights were dimmed at night to reduce visibility, and the factory windows were blacked out like eyelids.

The pressure should have broken them.

Instead, the lines held.

Not perfectly—nothing did—but better than anyone expected.

Evelyn moved between stations like a quiet supervisor without a title. She didn’t bark orders. She pointed at small things before they grew sharp teeth: a bin filling unevenly, a gauge drifting, a lubricant cycle missed, an operator rushing and making mistakes because fear made hands clumsy.

She was not heroic. She was simply stubborn about waste.

On the night the plant met the red-ink order, the entire floor seemed to exhale at once.

Men and women stood near the loading dock and watched crates being sealed, labeled, and carried onto trucks that idled like impatient animals. The crates were stenciled with numbers and destination codes. They looked ordinary.

But Evelyn knew what they were.

They were time.

They were momentum.

They were the difference between a planned advance and a stalled one.

Draper walked up beside Evelyn, hands in his pockets. His tie was gone. He looked more like a man and less like a foreman statue.

“You did good,” he said grudgingly.

Evelyn blinked. “We did,” she corrected, uncomfortable with singular credit.

Draper snorted. “Fine. You started it.”

Evelyn watched the trucks roll away into the dark street, their headlights hooded, their engines low.

“Do you think it matters?” she asked quietly.

Draper looked at her, and for a moment his face softened in a way she hadn’t seen before.

“In a war,” he said, “everything that keeps the machine running matters.”

Evelyn nodded slowly.

Months later, long after the red-ink rush had become another line in a ledger, Evelyn received a letter with no return address and an official stamp that made her hands shake.

It wasn’t from someone she knew. It wasn’t personal. It was short, almost painfully plain:

“To the workers of the ammunition plant: increased shipments arrived on schedule. The operation proceeded without delay. Your work contributed materially to success.”

No names. No stories. No dramatic thanks.

But Evelyn read it three times anyway.

She carried it folded in her pocket for days, not to show anyone, but because the paper felt like proof that her life in a loud factory hadn’t been swallowed by anonymity.

On a quiet Sunday, she walked along the river and watched it move under gray sky. The world looked almost normal, as if war were just a distant thunder.

Evelyn thought about the day she’d walked upstream to the press, the day she’d dared to speak to a man who didn’t expect to be corrected by a girl in overalls.

She thought about how small the fix had been: a gauge, a gate, a change in where you looked.

A small idea.

Dirt cheap.

And yet it had multiplied output the way a lever multiplies force—not by magic, but by changing where effort mattered.

She smiled faintly, not with pride, but with a quiet relief that felt almost like peace.

Because the war would be remembered with headlines and generals and maps with thick arrows.

But somewhere inside those arrows, inside those offensives, inside that relentless momentum, there would be the invisible work of people like her—people who didn’t carry rifles, but carried the war’s heartbeat in the form of steady production.

And sometimes, Evelyn realized, saving an offensive wasn’t about one dramatic act.

Sometimes it was about preventing the jam before it happened.

Sometimes it was about catching a flaw where it began, not where it hurt.

Sometimes it was a nineteen-year-old factory girl, tired of waste, who decided the machines would not steal minutes anymore.

And that decision—quiet, practical, stubborn—could save far more than anyone would ever know.

News

“Dad, She’s Freezing!” the Single-Dad CEO Said as He Wrapped His Coat Around a Homeless Stranger—Years Later the Woman He Saved Walked Into His Boardroom and Ended Up Rescuing His Company, His Daughter, and His Heart

“Dad, She’s Freezing!” the Single-Dad CEO Said as He Wrapped His Coat Around a Homeless Stranger—Years Later the Woman He…

They Set Up the “Grease Monkey” on a Blind Date as a Cruel Office Prank—But When the CEO’s Smart, Beautiful Daughter Sat Down, Took His Hand, and Said “I Like Him,” the Joke Backfired on Everyone Watching

They Set Up the “Grease Monkey” on a Blind Date as a Cruel Office Prank—But When the CEO’s Smart, Beautiful…

How a Quiet Homeless Woman Risked Everything to Save a Child from a Burning Apartment—and Why a Determined CEO Searched the City for the Mysterious Hero Who Disappeared Into the Smoke

How a Quiet Homeless Woman Risked Everything to Save a Child from a Burning Apartment—and Why a Determined CEO Searched…

For Eight Dollars You Can Have My Wife,” the Drunk Gambler Laughed in the Saloon — The Quiet Rancher Slapped Coins on the Table, Took Her Hand, and Turned a Cruel Joke into a Deal Nobody Expected Him to Honor

For Eight Dollars You Can Have My Wife,” the Drunk Gambler Laughed in the Saloon — The Quiet Rancher Slapped…

How a Lonely Rancher’s Grasp on a Stranger’s Wrist Stopped a Silent Standoff on the Plains and Led to an Unlikely Bond That Changed Two Destinies Beneath the Endless Western Sky

How a Lonely Rancher’s Grasp on a Stranger’s Wrist Stopped a Silent Standoff on the Plains and Led to an…

When a Lone Rancher Walked into Court and Told the Truth About the Judge’s Wife, the Whole Town Gasped—Because What He Forced Her to Remember Was Worse Than Any Bullet or Branding Iron

When a Lone Rancher Walked into Court and Told the Truth About the Judge’s Wife, the Whole Town Gasped—Because What…

End of content

No more pages to load