The Afternoon General George S. Patton’s Temper Ignited a Private War in Eisenhower’s Headquarters, Forcing the Supreme Commander to Choose Between Victory, Discipline, and a Friend Who Refused to Back Down

By the summer of 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower had seen just about every kind of problem a war could throw at a man.

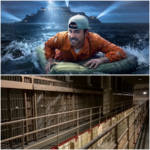

He’d dealt with storms that scattered a massive invasion fleet, rival commanders who thought their front was the only one that mattered, and endless telegrams from leaders back home asking why things weren’t moving faster. He’d learned that command, at his level, wasn’t about winning one big battle—it was about keeping an entire, fragile machine moving forward without tearing itself apart.

But there were days when the real storm walked into his headquarters on two legs, wearing polished boots and ivory-handled pistols.

On this particular afternoon, that storm was named George S. Patton.

The headquarters was an old French manor house, its walls thick and weathered, its windows open to let in warm air that smelled like dust and distant fields. Jeeps came and went in the driveway. Typewriters clicked inside. Radios crackled, phones rang, aides hurried through corridors with arms full of maps and folders.

In one of the bigger rooms, now stripped of paintings and crowded with tables, a handful of senior officers bent over a large map spread across a wooden surface. Colored pins marked divisions. Thin strings traced supply routes. Circles showed enemy positions—estimated, adjusted daily, always naggingly uncertain.

Eisenhower stood at the head of the table, sleeves rolled up, tie slightly loosened, a pencil in his hand.

“Bradley’s pushing here,” Ike said, tapping a point on the map. “Montgomery wants more trucks up north, as usual. And down here—”

The door opened without a knock.

George Patton filled the doorway, his presence like a sudden gust of wind. He wore his helmet under one arm, the other hand gloved and resting on the butt of one of his holstered pistols. His uniform was immaculate. His eyes were sharp, bright with an energy that never seemed to dim.

“Ike,” Patton said, not bothering with rank.

Conversation in the room snapped off like a radio switched to OFF. Aides exchanged quick glances. Eisenhower didn’t look surprised. He’d been expecting this.

“All right, gentlemen,” Ike said evenly. “Give us the room.”

Chairs scraped. Papers were gathered. Officers filed out, some doing their best not to stare too openly at Patton. In the hallway, a murmur started immediately: What’s he doing here? Did they call him in? Is it about the latest incident?

They all knew something had happened—something that had started as a rumor and turned, as those things did, into a story told in low voices over late-night coffee.

When the door shut, it left Eisenhower and Patton alone with the map, the quiet, and a tension you could almost feel in the air.

Eisenhower set his pencil down.

“You’re early,” he said.

“Couldn’t wait,” Patton replied. His voice was steady, almost casual, but his jaw had that familiar tightness. “I hear you’ve got concerns about my conduct again.”

“Sit down, George,” Ike said.

“I prefer to stand.”

Eisenhower held his gaze for a moment, then shrugged and stayed standing too.

“Fine,” he said. “Let’s talk as we are.”

Patton walked closer to the table, studying the map as if it were an old adversary. He traced the line of his own army’s advance with his eyes. Where others saw colored pins, he saw fields, rivers, exhausted men, broken vehicles, and opportunities.

“We’re moving fast,” Patton said. “Faster than anyone thought we could. My boys have taken towns that were supposed to hold for weeks. We’re breaking their spine.”

“Your speed isn’t the issue,” Eisenhower replied. “Nobody’s arguing with your results on the ground, George.”

“Then what is the issue?” Patton snapped.

Ike picked up a folder sitting near the edge of the table. It was worn at the corners, the top sheet covered in typed lines and hand-scribbled notes. He’d been staring at it for two days now, weighing every word.

He opened it and pulled out a single sheet.

“This is a statement from your own medical staff,” Eisenhower said. “They’re upset. They say your remarks are undermining their work. Making it harder for them to treat men who are already struggling.”

“Struggling,” Patton said, almost tasting the word. “You mean men who’ve lost their nerve.”

Eisenhower felt a flash of temper, but kept his voice steady. “You know better than that. You’ve seen combat yourself. You know what it does to people.”

“And I’ve seen what happens when you let fear spread,” Patton said. “One man folds, then another, then a whole unit starts looking for excuses instead of targets. We’re not training a club out there, Ike. We’re fighting a war.”

He took a step closer, planting his gloved hand on the map, right over the thin line of his advance.

“You want fast progress?” he continued. “You want bold moves? That doesn’t come from feeding every doubt and soft feeling. It comes from demanding more than a man thought he had, and then one ounce more after that.”

“And what about the men who don’t have one ounce more?” Eisenhower asked quietly. “What about the ones who are spent in ways we can’t see?”

Patton’s expression hardened. “War doesn’t care about invisible wounds.”

“I do,” Ike shot back. “And so does every doctor trying to keep those men from shattering completely.”

Outside the room, in a narrow hallway lined with cracked plaster, a young captain named Harris pretended to study a bulletin board while keeping an ear tilted toward the door. He couldn’t hear words, just tones—Eisenhower’s firm, controlled baritone, Patton’s sharper, more forceful cadence.

Beside him, a major shook his head.

“This is going to blow up,” the major said under his breath. “You can’t keep two men like that in the same room with something like this between them.”

Harris swallowed. “You think they’ll…?”

“Who knows,” the major replied. “I just know you don’t get called to headquarters to talk about good news.”

He glanced down the corridor, where other staff officers hovered, trying to look casual and failing. Word had traveled faster than any official memo: Patton had gone too far—again. This time, the story went, his harsh words about “nerves” and “courage” had cut into more than one soldier, and more than one doctor.

This time, even some of his own officers were uneasy.

Back inside, Eisenhower laid the paper flat on the table between them.

“George,” he said, dropping the rank now, “I have to be able to stand in front of every commander and every government back home and say that we’re doing this war the right way. Not a perfect way—we both know there’s no such thing—but a way that respects the men we’re asking to do the impossible.”

Patton crossed his arms. “And you think I don’t respect them?”

“I think,” Eisenhower said carefully, “you respect a certain kind of man. The ones who remind you of yourself.”

Patton blinked, caught off guard for a fraction of a second.

“You admire the ones who push past everything,” Ike continued. “Pain, fear, doubt. You see yourself in them—your best self. The warrior who never yields. But this war isn’t fought just by that kind of man. It’s fought by farm boys, clerks, mechanics… some of whom reach their limit and need help, not condemnation.”

Patton’s eyes flashed. “You’re saying I’m unfit to command them?”

“I’m saying,” Eisenhower replied, “that your words carry further than you think. They don’t just harden spines. Sometimes they break them.”

For a long moment, neither man spoke.

The afternoon light slanted in through the window, falling across the map. Distantly, a truck backfired. A telephone rang in some other room. The war went on, indifferent to two generals facing each other in a borrowed French manor.

“You know what the real problem is, Ike?” Patton said finally. His voice was lower now, not quite so sharp. “You’re afraid of what people will say back home.”

Eisenhower’s jaw tightened. “I’m responsible to the people back home.”

“You’re responsible for winning,” Patton shot back. “That’s why they gave you this job. That’s why men like me follow your orders instead of chasing our own glory. You start worrying about headlines more than victory, and we’re in trouble.”

“Don’t you dare tell me what I’m worried about,” Ike said, and this time the steel in his voice made Patton’s eyes narrow. “You think I don’t wake up every night counting casualties? You think I don’t see names and faces when I sign orders?”

He took a breath, then another, steadying himself.

“You and I want the same thing,” he went on, more controlled. “A swift victory. Fewer graves. A world put back together. But if we lose ourselves along the way—if we trample every principle we claim to be fighting for—then what did we actually win?”

Patton stared at him, and for a heartbeat, something like sadness passed behind his eyes.

“I’ve never had the luxury of thinking about principles when bullets start flying,” he said. “All I know is that hesitation gets men killed.”

“And cruelty also gets men killed,” Eisenhower replied. “Sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly, as the weight of it spreads.”

The argument rose and fell, like a tide coming in too fast.

At times, it sounded almost like two old friends sparring, each pushing the other, trying to knock loose some stubborn belief. At other moments, it felt like a crack in the very structure of the command—a fracture between two different visions of what it meant to fight and lead.

Patton argued that fear had to be crushed, not accommodated. That the enemy wouldn’t show mercy, so neither could they—not even with their own weakness.

Eisenhower argued that the strength of their side lay precisely in the way they treated their own. That they couldn’t preach courage and decency while humiliating the very men who bore the cost of each advance.

Patton spoke of urgency, of precious momentum that could be lost if people started treating exhaustion like an excuse.

Eisenhower spoke of endurance, of a war that wasn’t going to be decided in one bold charge, but in months and months of sustained effort by men whose minds and hearts needed care as much as their bodies.

The more they talked, the more the air between them thickened.

For the first time since this campaign had begun, Eisenhower felt something he’d always managed to keep at bay with Patton: the sense that the man in front of him might be more liability than asset.

For the first time, Patton felt something he’d rarely experienced with Ike: the fear that his commander was drifting toward a kind of leadership that he, George Patton, simply could not follow.

“Let me ask you something,” Eisenhower said at last. His voice was tired now, but still steady. “If every doctor in this theater walked out of their tents tomorrow and told me, ‘Sir, we can’t do our jobs because your generals are undoing everything we stand for,’ what should I do?”

Patton frowned. “You’d replace the doctors,” he said, as if it were obvious. “Find some who understand that their duty is to get men back on their feet, not hold their hands.”

“I’d lose the war,” Ike said flatly. “That’s what I’d do.”

He shook his head.

“I need those doctors as much as I need your tanks,” he continued. “I need the chaplains, the engineers, the cooks, the clerks. I need the quiet men who keep the supply lines moving just as much as the loud ones who rally an attack. This whole machine falls apart if I tell one part, ‘You don’t matter as much as the other.’”

Patton’s voice turned sharper. “You start treating everyone the same, you drag the strong down to comfort the weak.”

“And if I start dividing men into ‘strong’ and ‘weak,’” Eisenhower countered, “I forget that any man can be both at different times—and that a leader’s job is to bring him back from the edge when he’s slipping, not kick him off the cliff.”

There it was—the heart of it.

Two philosophies. Two kinds of faith in human nature.

Patton’s: that a man becomes his best only under unrelenting pressure.

Eisenhower’s: that pressure needed to be balanced with understanding, or it would turn men into something less than what they were.

The room felt smaller now.

Patton turned away, staring out the window at the courtyard below. A vehicle pulled in, dust swirling around its tires. A driver jumped out, saluted a guard, began unloading crates.

“You know why they listen to me out there?” Patton asked without turning around.

“Because you win,” Ike said. “Because you inspire them. Because you’re relentless.”

“That’s part of it,” Patton said. “But the real reason is simpler. They know I won’t ask them to do anything I wouldn’t do myself. They know that if I call them cowards, it’s because I’d rather die than be what I’m calling them.”

He finally turned back, eyes bright.

“I’m not standing above them, judging from a distance,” he said. “I’m right there in the mud with them—in spirit if not in body. When I tell them to push, they know it’s coming from a man who’s burned his own nerves raw for the same cause.”

Eisenhower studied him for a long moment.

“I don’t doubt your courage, George,” he said quietly. “I never have. But courage doesn’t give you the right to wound men whose injuries you can’t see. That’s the part you never quite accept.”

For the first time, Patton faltered. Just a little.

“I’m trying to win this thing,” he said. “That’s all.”

“So am I,” Eisenhower replied. “And I have to think about the day after we win, too. The day these men go home and have to live with what they’ve been through—and how we treated them.”

Silence settled, heavy and thick.

Eisenhower knew he had reached the point he’d been dreading. The point where this could no longer be a private disagreement between two strong personalities. The point where he had to decide if Patton’s way of being a general still fit inside the kind of war Eisenhower was trying to run.

He picked up a paper from the folder—an order he’d drafted, revised, set aside, and picked up again so many times the edges were starting to curl.

“George,” he said, “this can’t just end with ‘we disagree.’ There has to be a line. And this time, you crossed it.”

Patton’s eyes dropped to the paper.

“You’re going to relieve me,” he said. Not a question, but a simple, flat statement.

Eisenhower felt the weight of the moment settle on his shoulders. He thought of all the times Patton had come through for him. The daring moves. The rapid advances. The way Patton’s presence alone could electrify a tired unit.

He also thought of the angry letters from worried families. The quiet testimony of medical officers. The frightened, ashamed look on a young soldier’s face as he described being treated like a failure for something he couldn’t explain.

“No,” Ike said. “I’m not going to relieve you.”

Patton blinked.

“I’m going to suspend you,” Eisenhower continued. “You’re stepping back from front-line command for a period. Officially, it will be explained as a rotation, a reassignment while we ‘review’ certain concerns. Unofficially, you and I both know what it is: a warning, and an opportunity.”

“An opportunity for what?” Patton asked, voice stiff.

“To decide whether you can keep being who you are and be the kind of commander this war needs,” Eisenhower said. “To let the dust settle. To let people remember your victories without your temper being the first thing that comes to mind.”

Patton’s face flushed.

“You’re bowing to politics,” he said. “To doctors, reporters, nervous staff—”

“I’m bowing to the reality that this army is bigger than either of us,” Ike interrupted firmly. “Bigger than your legend. Bigger than my reputation. Bigger than the version of war any one man carries in his head.”

The words landed like blows.

Patton straightened, shoulders rigid.

“How long?” he asked.

“I don’t know yet,” Eisenhower admitted. “Long enough for the men you hurt with your words to see that there are consequences. Long enough for the people watching from the outside to know that we take this seriously. But not so long that we forget that, when you’re at your best, you’re one of the most effective commanders we have.”

He stepped closer.

“I’m not throwing you away, George,” he said quietly. “I’m giving you a chance to come back. But if you do, it has to be with a different understanding of the men under you.”

Patton’s throat moved as he swallowed.

“And if I don’t come back?” he asked.

“Then that will be your choice,” Ike replied. “But the war will go on. It has to.”

Outside the door, Captain Harris heard footsteps and jerked away from the wall, suddenly fascinated by a totally unimportant memo. The door opened.

Patton strode out first, his face a mask carved in stone. He didn’t look at anyone. Boots striking hard against the floor, he moved down the hallway with the same iron posture he always carried, but there was something different in the air around him. Something heavier.

Eisenhower emerged a moment later, the folder in his hand.

The staff officers didn’t ask questions. They didn’t have to. Word would come down soon enough.

But as the day wore on, the story began to take shape anyway:

Patton had gone too far.

Eisenhower had finally drawn a line.

And somewhere between those two facts, an argument had taken place that left both men changed.

In the months and years that followed, people would argue about that day.

Some would say Eisenhower had been too cautious, that he had muzzled his most aggressive commander at a time when boldness was the sharpest weapon they had. Others would say he’d done exactly what a leader should do: remind everyone that greatness on the battlefield didn’t put a man above basic decency.

Some would insist Patton never truly changed—that he remained the same fierce, uncompromising spirit to the end. Others would point to more measured words in later speeches, small gestures of respect toward men who had bent but not broken.

Historians would comb through letters and diaries, trying to reconstruct every detail of that meeting. Nobody ever got it quite right, because paper couldn’t capture the way the air felt in that room, the way old loyalty and new reality collided, the way two strong men struggled to stay on the same side of a war that was testing more than just armies.

But a few things were clear.

On that afternoon, in a borrowed French manor, George S. Patton finally pushed past a line Dwight D. Eisenhower could not ignore.

The resulting confrontation was not a simple rebuke, nor a simple defense.

It was a hard, painful negotiation over what kind of victory they were trying to win—and what kind of men they were willing to be to get there.

Eisenhower walked away carrying the weight of a decision that would follow him for the rest of his life.

Patton walked away with his pride wounded deeper than any shrapnel could reach, but with a door still open—if he chose to walk back through it on different terms.

And the war rolled on, carried forward not just by tanks and planes and strategies, but by millions of human hearts, each one fragile, each one shaped by the choices of leaders who argued behind closed doors over where courage ended and cruelty began.

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load