“Married at 17 Against Her Will, Locked Away, Separated From Her Daughters, Teresa Wilms Montt Escaped to Write Explosive Books and Wander the World’s Cities — From Buenos Aires to Paris — Defying Church, Family, and Men in a Scandalous Life That Shocked Her Era and Still Fascinates Today.”

Teresa Wilms Montt: The Woman Who Refused to Ask Permission to Exist

“I am Teresa Wilms Montt… and I’m not fit for no ladies.”

It was more than an introduction. It was a declaration of war against the rigid molds of early 20th-century Chilean society. Born in 1893 into an aristocratic family, Teresa Wilms Montt was expected to live a life already written: marry young, obey quietly, pray dutifully, fade gracefully.

She refused every line of that script.

A Childhood in a Cage

Teresa was born into privilege, but privilege came with chains. The Wilms family was strict, traditional, and obsessed with appearances. Women were expected to smile politely, never contradict men, and accept decisions made for them.

Even as a child, Teresa rebelled. She questioned priests. She ignored etiquette. She devoured books in Spanish, French, and English, languages she would later use to craft her own voice. Her intelligence dazzled, but it also frightened a society unprepared for women who thought too freely.

Forced Marriage, Forbidden Love

At 17, she was married off to Gustavo Balmaceda, a union arranged by her family. It was not love.

The young Teresa loved another — a scandal that was unforgivable in a conservative society. When her family and husband discovered her secret, punishment was swift and merciless.

She was locked away in a convent. Stripped of freedom. Separated from her two daughters. Surrounded by silence meant to break her spirit.

But Teresa was not a woman who bent easily.

The Escape

Against every expectation, she escaped.

She fled the convent and the suffocating grasp of her family. In the years that followed, she would live as few women of her time dared: on her own terms, wandering the great capitals of the world — Buenos Aires, Madrid, New York, Paris.

Her companion during part of this journey was the avant-garde poet Vicente Huidobro. With him, she was introduced to literary circles, anarchist thinkers, and artists who saw in her not scandal, but brilliance.

Writing With Blood and Rage

Teresa wrote as if her veins were open on the page.

Her prose and poetry were searing, confessional, filled with fury and longing. She turned her diaries into literature. Her verses were not polished with academic detachment; they were raw, visceral, and alive.

In her short life, she published five books. Each one was celebrated by intellectuals, admired for its originality and depth. Her voice stood out in a literary landscape dominated by men.

She wrote like someone leaping from an abyss with her eyes open — not to be saved, but to experience the fall fully.

Always in Motion

She never stayed still. Teresa lived between continents, constantly moving, always chasing both freedom and exile.

In Buenos Aires, she dazzled literary salons with her elegance and sharp wit. In Madrid, she debated anarchist philosophers. In New York and Paris, she absorbed the cultural revolutions of modernity.

But no matter where she went, she carried both admiration and condemnation. Admirers saw her as a muse, a genius, a rebel ahead of her time. Critics — especially those from her homeland — saw her as a scandal, a disgrace, a woman who refused to know her place.

Family Denial, World Recognition

Her family never forgave her. For them, she had crossed every forbidden line. She had shamed their name, broken tradition, abandoned “duty.”

But the intellectual world could not ignore her. Writers, artists, and thinkers celebrated her. They saw in her not only talent but courage. She embodied the radical possibility of a woman refusing to be silent in an age when silence was mandatory.

She was, as one critic later said, “a flame too bright for her century.”

The Woman Society Couldn’t Define

What unsettled people most about Teresa was not just her rebellion, but her refusal to fit any category.

She was elegant, yet she lived on the margins. She was aristocratic, yet she sympathized with anarchists. She was a devoted mother in longing, yet branded as unfit and kept from her daughters. She was both victim and rebel, fragile and fierce.

And above all, she was free — even when that freedom cost her everything.

Why Her Story Matters

Teresa Wilms Montt’s story is not just a tale of one rebellious woman in early 20th-century Chile. It is a mirror for every generation of women who have been told how to live, what to love, when to speak, and when to remain silent.

Her life reminds us that:

Conformity is not survival. Teresa chose authenticity, even when it meant exile.

Writing is resistance. Her books turned pain into art that outlived those who condemned her.

Freedom carries a cost. She lost her daughters, her family’s acceptance, and her place in polite society. But she gained something rarer: the right to define herself.

A Legacy Reclaimed

For decades, Teresa’s story was whispered more than studied, wrapped in scandal rather than celebrated. But in recent years, scholars and readers have returned to her work with fresh eyes.

Her diaries, poems, and prose reveal not just rebellion but vision — a woman who foresaw the battles of feminism, the struggles for identity, the cry for authenticity.

Today, she is remembered not as a scandal but as a pioneer. A woman who refused to ask permission to exist.

Final Reflection

“I am Teresa Wilms Montt… and I’m not fit for no ladies.”

That sentence was both a confession and a manifesto.

Teresa was a woman who lived in motion, who burned brighter than her society could tolerate, who turned pain into literature and exile into freedom.

Her family denied her. The world misunderstood her. But history, slowly, is beginning to recognize her: not as a cautionary tale, but as a figure of defiance, beauty, and brilliance.

She lived as she wanted — and for that, she paid the highest price.

Yet her words remain, carrying the truth she fought for: that no one, not even society itself, has the right to define who a woman should be.

News

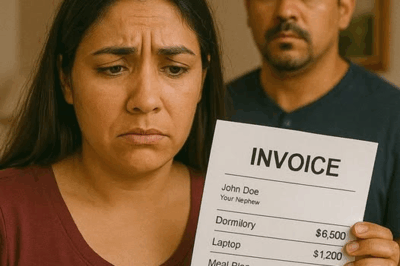

When My Brother Walked Into My Office With a $15,000 Bill and Said “Pay for My Son’s Education

When My Brother Walked Into My Office With a $15,000 Bill and Said “Pay for My Son’s Education,” I Didn’t…

☕ Story: “The Bracelet She Never Took Off”

“A Struggling Single Dad Was Just Trying to Buy His Daughter a Cupcake When He Saw His First Love Sitting…

🌅 Story: “The Birthday They’ll Never Forget”

“My Family Forgot My Birthday for the Fifth Year in a Row — So I Cashed Out My Savings, Drove…

🌙 Story: “The Sweater I Never Finished”

“‘You’re Just a Burden Now,’ My Granddaughter Whispered as She Slammed the Door — But a Week Later, She Found…

🏍️ Story: “The Table That Changed Everything”

“A Rude Manager Threw Out a Hungry Kid for ‘Ruining the Image’ — Ten Minutes Later, a Group of Bikers…

🌷 Story: “The Language of Silence”

“A Shy Waitress Thought No One Noticed Her Until a Billionaire’s Deaf Mother Walked Into the Café — When She…

End of content

No more pages to load