Six Minutes Over Midway: When One Missed Chance Gave Japan the Pacific, Shattered an American Pilot’s Faith, and Forced a Generation to Live with the Question of What Victory Really Meant

The first time Lieutenant Jack Hayes thought the ocean could burn, it was just after 10:30 a.m. on June 4, 1942.

The sky above Midway was a hot, brilliant blue. The clouds below were scattered cotton, drifting lazily over a Pacific that didn’t care which flag flew above it. Somewhere under that blue, men were already dying.

Jack’s SBD Dauntless dove-bomber roared at ten thousand feet, engine a steady, comforting growl beneath him. Sweat rolled down his spine, soaking the back of his flight suit, but his hands stayed steady on the stick. He’d practiced this run a hundred times in his head.

Find the enemy carriers. Dive out of the sun. Drop at fifteen hundred feet. Pull up. Watch the bomb hit where the deck met the island. Sailors called it the “golden run.”

He glanced left. His wingman, Barker, waggled his wings once—you good?—and Jack answered with a quick waggle back. He could just make out Barker’s grin through the canopy. Barker always grinned. It was annoying and reassuring at the same time.

“Scorpion Lead, this is Scorpion Two,” came the crackle in his headset. Barker’s Texas drawl sounded thin through the static. “I’m not seeing anything but blue as far as the eye can see.”

“Stay sharp, Two,” Jack said. “They’re out here. They didn’t sail the whole Imperial Navy home just because we asked nice.”

Up ahead, at the front of their small formation, Lieutenant Commander Wade, their group commander, banked his plane slightly, scanning.

They’d been in the air for hours. The world had turned into a hazy watercolor of sky and sea, with Midway somewhere behind them and history somewhere ahead.

Jack thought of the briefings, the maps with red arrows, the calm voice of Admiral Spruance explaining how this would work—how it had to work.

“Intelligence says they’ll be here,” the Admiral had said, tapping a point on the map with his finger. “If we catch them with their decks full of planes refueling and rearming, we can cripple them in one stroke. Our carriers are outnumbered. This is our chance to even the odds.”

Six minutes. One window. They didn’t call it that yet. It was just a concept in a strategist’s head.

“Scorpion Lead to all Scorpion aircraft,” Wade’s voice came through, cutting through Jack’s thoughts. “Climb to thirteen thousand. Let’s get above the clouds, maybe we’ll spot something.”

The formation began to pull up, engines straining.

Jack scanned the horizon again, eyes stinging.

Nothing.

No carriers. No escorting cruisers. No destroyers carving white scars through the blue. Just empty ocean.

A tickle of worry crept under his collar.

“Maybe the intel boys were wrong,” Barker muttered. “Wouldn’t be the first time.”

“Zip it, Two,” Jack said, though he was thinking the same thing.

They climbed.

At thirteen thousand, the air got thinner, colder. The clouds lay below them like dirty cotton, broken into drifting islands.

Jack swept his gaze left to right, slow and methodical, the way they’d taught him.

Then he saw it.

A thin pencil line of smoke on the horizon. Another. Another. Like someone had taken a charcoal stick to the blue.

“Scorpion Lead, this is Three,” Jack said, heart rate kicking up. “Bearing two-eight-five. Multiple smoke trails. Ships.”

“Copy, Three,” Wade replied. “All Scorpion aircraft, come right to bearing two-eight-five. We’ve got them.”

Finally, Jack thought.

They banked as one, turning toward the distant lines.

The next few minutes were a blur of motion and altitude adjustments. As they closed, the smoke became shapes. The shapes became ships. Carriers, their decks flat and brown, flanked by smaller vessels trailing white wake.

Jack squinted.

Something was off.

“Why aren’t they burning?” Barker asked, echoing Jack’s thought. “We were supposed to catch them after the torpedo boys hit.”

The plan—such as it had been—relied on timing. Torpedo bombers, slow and low, were to go in first, drawing fighter cover down and forcing the Japanese to maneuver. Then the dive-bombers would roll in from altitude, hitting carriers with their decks crowded and defenses scrambled.

But from up here, the Japanese fleet looked orderly. No smoke from burning fuel. No wild, weaving wakes. No chaos.

Just movement.

Calm.

Directed.

“Scorpion Lead, I’m not seeing any damage,” Jack said carefully.

“Neither am I,” Wade said. He sounded tight. “Maybe the Devastators are still inbound.”

“Or maybe…” Barker began.

“Don’t finish that sentence,” Wade snapped. “We’re here now. We make this count. Arm your bombs. Set dive flaps.”

Jack swallowed, fingers moving automatically to flip switches. The Dauntless shuddered slightly as the dive brakes extended.

“Enemy fighters!” someone yelled over the radio. “Zeroes, twelve o’clock high!”

Jack jerked his head up.

Tiny dots streaked down out of the sun—sleek, fast, beautiful in a way that made his stomach drop.

“Scorpion flight, break! Break!” Wade shouted.

The formation shattered. Jack rolled hard right, his stomach lurching as the horizon spun. Tracer rounds ripped through the space he’d occupied a heartbeat before.

Six minutes.

If they’d been just six minutes earlier, they would’ve found decks cluttered with planes, fuel lines strung like veins, crews exposed.

Instead, they’d found a sky full of Zeroes.

And below, a very calm, very ready Japanese fleet.

Jack shoved his stick forward, sending the Dauntless into its dive.

If death was coming anyway, he’d at least give it something to chew on.

2. Six Minutes Late

For a few seconds, the world narrowed to the scream of wind past the canopy and the black crosshairs of Jack’s bombsight.

The target carrier grew in the glass, its deck a neat brown rectangle striped with white lines. Men in tiny uniforms scrambled, pointing, running. A Zero flashed past, so close Jack saw the pilot’s goggles.

Tracer fire stitched the air around him. His plane jolted. A warning light blinked red on the panel.

“Come on, sweetheart,” he muttered to the Dauntless. “Hold together.”

At fifteen hundred feet, he punched the bomb release and pulled back hard. The Gs slammed him into his seat. His vision went gray at the edges.

He craned his neck as the plane clawed for altitude.

The bomb arced down toward the carrier.

For a moment, it looked perfect.

Then the carrier turned.

The ship heeled over, screws churning white. The bomb splashed into the sea just off her stern, sending up a useless plume.

“No,” Jack whispered.

Another Dauntless, Barker’s, dove in a second behind him. Tracers found it. The plane shuddered, trailing smoke. Barker held the dive anyway, released, tried to pull up.

He didn’t make it.

The Dauntless hit the water in a spray of white and fire. The bomb detonated a moment later, a boiling eruption that swallowed the aircraft whole.

“Barker!” Jack yelled, as if shouting the name could undo the last two seconds.

Static answered.

A Zero cut across his nose. Jack yanked the stick, trying to keep out of the gunsights behind him. His rear gunner, McKinney, opened up, the twin .30s chattering.

“Got one following us!” McKinney shouted. “He’s right on us, Lieutenant!”

“Hang on,” Jack said.

They twisted, dove, climbed, but the Dauntless wasn’t built to play with Zeroes. It was a workhorse, not a ballerina.

Something punched through the fuselage behind Jack. Another round starred the glass of his canopy. McKinney swore.

“Hit, but I’m okay!” the gunner yelled. “Just mad!”

Ahead, beyond the dance of death immediately around them, Jack saw something that made the bottom drop out of his stomach.

Columns of water erupted around one of the American carriers, far in the distance. Tiny black specks—dive bombers?—approached, then peeled away. Flames licked up from the carrier’s flight deck.

“Jesus,” Jack whispered.

In every briefing, every map, Midway had been presented as their chance to strike back. A trap. A bold move. If they caught the Japanese carriers, they’d cripple them.

Intelligence had done its job, they’d been told. They knew when and where the strike force would be.

But out here, in the burnt sugar smell of cordite and engine oil, it felt like the trap had snapped in the wrong direction.

“Scorpion Lead to all Scorpion aircraft,” Wade’s voice came over the radio, ragged. “If you’ve still got your bomb and can make another run, do it. Otherwise, get out of here. We can’t do anything floating.”

Jack glanced at his panel. No bomb. Fuel gauge dropping faster than felt comfortable. The sky crawling with Zeroes.

He made a choice.

“Scorpion Three to Lead,” he said. “I’m bugging out. McKinney took a hit. We’re not much good up here anymore.”

“Copy, Three,” Wade said. “Head east. Find the Big E if you can.”

Jack turned the Dauntless toward the vague direction of his own fleet. A Zero tried to cut across his path, but McKinney let loose another burst, driving the fighter off.

“Thought you said we were bugging out,” McKinney said.

“We are,” Jack said. “I just don’t feel like dying on the way.”

They limped away from the battle.

Behind them, the sky over the Japanese fleet flickered with explosions—not nearly enough of them. Flames crawled across the deck of an American carrier. Men leaped into the water, tiny specks in the vast blue.

Jack kept his mouth shut. If he tried to speak, he was afraid he’d start screaming and not stop.

Six minutes.

That’s all it took for one version of the future to burn and another to crawl out of the smoke.

3. Carrier Graveyard

They didn’t find the Big E—Enterprise—in the air.

They found her in pieces.

Jack and McKinney put the Dauntless down on the water because it beat the alternative of dropping out of the sky when the fuel finally ran dry. The landing was rough, the ocean a lot harder than it looked from above, but the plane stayed mostly intact.

They clambered out onto the wing, inflated the raft, and watched as their faithful SBD sank, bubbles gurgling up like laughter.

“Sorry, girl,” Jack murmured, patting the wet metal once before letting her go.

A few hours later, a destroyer scooped them out of the water. The deck of the Farragut felt weirdly alien under Jack’s boots—solid, noisy, crowded.

“Get them below,” a corpsman said, eyeing their torn flight suits. “Check for injuries.”

“I’m fine,” McKinney said. “Just angry.”

“Join the club,” Jack muttered.

They were handed dry clothes that didn’t fit quite right and strong coffee that tasted like boiled rope. Men moved around them with the brittle energy of people who’d just seen something they didn’t have words for yet.

“What happened?” Jack asked a sailor at the next table.

The man stared into his mug.

“Yorktown took it bad,” he said at last. “Hit by bombs, then torpedoes. She’s listing. They’re trying to save her, but…”

He didn’t finish.

“And Enterprise?” Jack’s voice felt too high in his own ears.

“Hit,” the sailor said. “Deck chewed up. She can still make steam, but she’s not launching much. We lost a lot of birds. And… and Hornet…”

He didn’t have to finish that sentence either. Jack saw it in his eyes.

Later, in the cramped briefing room, the truth came in pieces.

The torpedo squadrons—those slow, brave TBFs—had gone in first, as planned. They’d flown low and straight into a wall of flak and fighters. Few had made it to release point. Fewer had made it home.

Their sacrifice should have drawn the Zeroes down, opened a hole in the sky for the dive bombers.

But the timing had been off. Cloud cover had delayed one group. A misread bearing had sent another too far north. A handful of minutes here, a few there, and suddenly the dive bombers weren’t rolling in on a fleet caught off guard.

They were arriving late to a sky already full of sharks.

By the time the smoke cleared enough to see, three American carriers were crippled or sinking. The Japanese, battered but far from broken, still had enough flight deck left to launch follow-up strikes.

The reports were a blur—ships hit, units lost, a litany of steel and blood.

Jack sat through it all, the words washing over him.

When Admiral Nimitz’s message came through later, terse and weighed down with more than ink, the tone of the room shifted further.

MIDWAY LOST. CARRIERS HEAVILY DAMAGED. PRIORITY NOW DEFENSE OF HAWAII AND WEST COAST. FURTHER OFFENSIVE ACTION SUSPENDED UNTIL CARRIER FORCE RECONSTITUTED.

“We didn’t just lose ships out there,” Miller said quietly, later, when he cornered Jack in a passageway. “We lost the initiative.”

Jack stared at him. “We were supposed to turn the tide here,” he said, hearing how hollow it sounded.

Miller shrugged, but his eyes were tired. “Tides go both ways.”

4. The Argument

Pearl Harbor looked different the second time Jack arrived.

The first time, in late 1941, it had been all brass bands and bustle, the docks crowded with men in pressed whites and ships gleaming in the sun.

Now, in mid-1942, it was damaged steel and hard stares. The scars from the December attack were still there—twisted metal, oil stains on the water, the ghostly outline of the Arizona. Now they would have to make room for the battered survivors of Midway.

Jack found himself in a makeshift briefing hall—a converted warehouse—along with other pilots, gunners, officers. Maps of the Pacific were pinned to the walls, covered in pins and lines.

A commander from intelligence—a lean man with sharp features and glasses that never seemed to stay clean—stood at the front, pointer in hand.

“The key thing to understand,” he said, “is that Midway was a near-run thing. We had their plans. We had their timing. We were within a hair’s breadth of pulling off a decisive victory.”

“A hair we missed,” someone muttered.

The intel officer ignored it. “A variety of factors affected the outcome—weather, timing of launches, enemy reactions. Our torpedo squadrons—God bless them—went in as ordered but were decimated. Our dive-bomber groups were unable to coordinate their attacks effectively.”

He tapped the map where the Japanese carrier force had been.

“Had our dive-bombers arrived six minutes earlier,” he said, “they would likely have caught two, possibly three enemy carriers with aircraft on deck, fuel lines exposed. Instead, they found decks cleared and CAP—combat air patrol—reconstituted. Our timing cost us dearly.”

“Timing,” Jack heard himself say, before his brain could catch up to his mouth. “Is that what we’re calling it now?”

Heads turned. The intel officer frowned.

“I’m sorry, Lieutenant…?”

“Hayes,” Jack said. “Scorpion Three, SBD squadron. We didn’t ‘arrive late’ like we overslept. We got jumped. We were outnumbered and outflown. We went in anyway.”

“Lieutenant Hayes,” the officer said, a certain patience flattening his tone, “no one is questioning your bravery or your actions under fire.”

“Sounds like you’re questioning something,” Jack shot back. “We were up there alone. No torpedo planes to coordinate with because they were already at the bottom. No clear picture because the weather decided not to cooperate. But sure, let’s call it a timing issue.”

Murmurs rippled through the room. Some pilots nodded, others shifted uncomfortably.

The officer’s jaw tightened. “War is, in part, a matter of timing,” he said. “Of opportunities seized or missed. Our job now is to understand why this one was missed so we don’t repeat it.”

“Oh, I can tell you why,” Jack said, anger loosening his tongue. “Because we keep pretending we can choreograph chaos like it’s a parade. Because men with pens and maps think six minutes is a thing you can order up like coffee. Out there, sir, six minutes is everything. Or nothing. Sometimes it just… happens.”

The intel officer’s eyes flashed. “With respect, Lieutenant, intelligence gave you the enemy’s position, composition, and probable time of attack. We broke their codes. We listened to their traffic. We gave you the where and when. What we can’t do is fly the planes for you.”

A few of the officers in the room winced.

Jack’s vision narrowed. “You think we don’t know that?” he said. “You think Barker didn’t know that when his plane took three hits and he stayed in the dive because maybe, just maybe, he could put a bomb where it counted? He didn’t miss because his watch was off. He missed because the ship moved.”

“Lieutenant, that’s enough,” another voice cut in. Jack turned to see his squadron commander, Wade, standing near the back, expression unreadable.

Jack swallowed, realized his hands were clenched into fists.

“Sorry, sir,” he muttered, not sure who he was apologizing to.

The intel officer’s expression cooled by a few degrees. “We’re all angry,” he said after a beat. “We all lost friends out there. My brother was on the Yorktown. I’m not standing here because I enjoy dissecting failure. I’m doing it because the next time we get a six-minute window, I’d like us to be the ones who make it count.”

The room went quiet.

Wade stepped forward. “We’re not going to solve this by eating our own,” he said. “Intelligence did its job. We did ours as best we could in the situation. The enemy had a say, too. They get a vote in this war.”

He looked at Jack. “But Hayes is right about one thing. We can’t pretend this was just a scheduling glitch. Men died because we were outnumbered and outgunned at the point of contact. We need more carriers. More planes. More practice. Not just better clocks.”

“Agreed,” the intel officer said.

Jack sank back into his seat, heat still in his face.

The argument hadn’t fixed anything. The carriers were still on the bottom. Midway was still lost. But at least, for a moment, he’d said what was boiling in his chest.

Later, as the room emptied, Wade caught up with him.

“Walk with me,” the commander said.

They stepped out into the Hawaiian evening. The air smelled of salt and diesel and the faint sweetness of flowers trying their best to grow around the war.

“You want to know what I was thinking up there?” Wade asked, hands in his pockets.

“Sir?” Jack said.

“When we rolled in and saw those decks clear,” Wade said. “When the Zeroes came down on us like hawks on rabbits. You want to know what went through my head?”

Jack glanced at him. “Yes, sir.”

“I thought,” Wade said quietly, “‘We’re late.’ Not because we were lazy or stupid. Because up there, the difference between ‘just in time’ and ‘too late’ is a handful of heartbeats. That’s all the intel officer was trying to say. He just doesn’t know how to say it without sounding like a slide rule.”

Jack let out a breath. “Maybe,” he admitted. “I just… Every time someone says ‘if only you’d been six minutes earlier,’ it feels like they’re saying Barker died on the wrong side of a stopwatch.”

Wade nodded slowly. “I get it,” he said. “But here’s the thing, Hayes. The brass is right about one thing. Six minutes did change everything. Just not the way they like to frame it.”

“How’s that?” Jack asked.

“We thought we’d come out here, land a punch, and send them reeling,” Wade said. “Instead, Midway woke us up. Showed us they’re not going to just fumble their way into losing this war. We’re going to have to earn every inch.”

He looked out at the harbor, at the silhouettes of damaged ships against the darkening sky.

“We lost Midway,” he said. “We lost carriers we couldn’t afford to lose. That’s real. But as long as we’re still floating, still flying, the story’s not finished.”

Jack nodded, though the knot in his chest remained.

“Get some sleep, Hayes,” Wade said. “You’re no good to anyone if you burn out before the next round starts.”

“Yes, sir,” Jack said.

He tried.

Sleep didn’t come easy.

Every time he closed his eyes, he saw Barker’s plane hit the water and vanish.

5. Midway Falls

The Japanese flag went up over Midway two weeks later.

Jack didn’t see it in person. He saw the grainy reconnaissance photos in a briefing, the white coral sand of the atoll now adorned with rising sun banners and new construction.

“Enemy forces have occupied Midway and begun fortifying the airfield,” the intel officer—now a familiar face—said, pointing to the pictures. “They’ve brought in engineers, heavy equipment. They intend to use it as a forward base.”

A murmur went through the room.

“Can we take it back?” someone asked.

“Not right now,” the officer said. “Our carrier force is severely diminished. The Enterprise is heading back to the West Coast for repairs. The Yorktown is gone. Hornet is gone. The Japanese still have at least three operational fleet carriers in this sector, possibly four. Without parity at sea, any attempt to retake Midway by force would be… unwise.”

“So we just let them sit on our doorstep?” the same voice challenged.

“For the moment,” the officer said.

The new orders reflected the new reality.

No more audacious islands-hopping dreams. No talk of “offensive spirit.” Not yet.

Instead: defense.

Shore up Hawaii. Patrol the sea lanes. Build new carriers as fast as American factories could churn them out. Use submarines to harass Japanese supply lines, buy time with steel tubes and silent torpedoes.

Jack was assigned to a stateside training squadron for a while, teaching fresh-faced kids how to dive without blacking out and how to keep a level head when the sea rushed up toward them.

He hated it.

Every day he spent over American soil felt like a betrayal of the boys still out there, fighting over someone else’s island or clinging to a life raft.

But he did it. Because those kids needed someone who’d been there, someone who knew that “slight flak expected” meant “it will feel like flying through a steel storm.”

In the evenings, he read newspaper headlines in the mess hall.

MIDWAY BASE LOST—NEW DEFENSE LINE DRAWN AROUND HAWAII

JAPANESE FLEET MASSES IN CENTRAL PACIFIC

CARRIERS BEING BUILT IN RECORD TIME, ADMIRALTY SAYS

Stateside, people tried to carry on. There were ration lines and victory gardens and posters urging citizens to do their part. There were also whispers that the war in the Pacific might drag on for years.

“Six minutes,” Jack muttered one night, tossing the paper aside. “Feels like four more years.”

McKinney, seated across from him, looked up from his coffee. “What’s that?”

“Nothing,” Jack said.

But it wasn’t nothing.

In Tokyo, in a room half a world away, Commander Haru Sato ran his fingers over a different set of maps.

He’d been the air operations officer on the carrier Akagi during the Midway operation. When American dive bombers had failed to sink his ship in that crucial window, some had called it luck. Sato called it timing, training, and a healthy respect for coincidence.

Luck, he believed, was just what people called the parts of reality they didn’t understand.

Now, months later, he looked at the map of the Central Pacific with a strategist’s eye.

Midway, once a tiny dot on charts he’d barely glanced at, now sat inside a circle of ink.

A forward base. An outpost. A stepping stone.

“From here, our reconnaissance planes can reach much farther east,” his superior said, indicating arcs of range. “We can threaten Hawaii more directly. Perhaps even bombard it again. Their people will grow tired of this. Their politicians will look for a way out.”

Sato nodded, but he wasn’t entirely convinced.

He’d seen American pilots at Coral Sea and now at Midway—reckless, brave, sometimes foolish, but rarely cowardly. He doubted they’d be easily intimidated.

“What about their construction?” Sato asked. “The reports say they are building carriers rapidly.”

His superior, Vice Admiral Nagumo, waved a hand. “Even if they launch new hulls, their crews will be green. Their pilots untested. The Empire’s flyers are the finest in the world. We have proven this.”

Sato thought about the last Midway attack. How even under heavy fire, damaged American planes had pressed home their attacks. How some had broken up in the dive and still dropped their bombs as if by pure will.

He did not voice his doubt. Not yet.

“Of course, sir,” he said.

6. Long Shadows

By 1944, the shadows of those six minutes at Midway stretched across the world.

The war in Europe carved its own bloody path, but in the Pacific, everything that had seemed so inevitable in our timeline shifted.

Without the hammer blow of a decisive American victory at Midway, Japanese naval power remained formidable for longer. Their carriers, bloodied but afloat, continued to contest the seas around the Central Pacific.

The United States still had industrial muscle. Carriers rolled off the slips at Newport News and Brooklyn and San Francisco. Planes filled the decks, engines humming, pilots in crisp new flight jackets.

But every time a new task force pushed west, Midway loomed on the map like a raised fist.

Its airfield launched patrols that stretched Japanese eyes farther east. Its harbor sheltered submarines that prowled the shipping lanes.

There were battles—there were always battles. The Enterprise, patched and bitter, led strikes against island airfields. American submarines sank tankers and freighters, slowly choking Japanese supply lines. The Solomons campaign still happened, but it was harder, bloodier, the enemy receiving more support from a Midway that refused to be neutral.

Jack spent 1943 and 1944 bouncing between carriers and island bases. He flew in strikes against Tarawa, against the Marshalls, against places whose names blurred together in his memory—just more specks of sand bought with blood.

Sometimes, in the ready room before a mission, someone would bring up Midway.

“If we’d won there,” a young pilot named Carter said once, “we’d already be knocking on Tokyo’s door.”

Jack said nothing.

McKinney, now a grizzled presence in the back of the room despite being only a few years older than most, spoke instead.

“If we’d won there,” he said, “some of us wouldn’t be here to complain about not winning fast enough.”

The room went quiet.

“Midway messed everything up,” Carter said later, when it was just him and Jack and a shared cigarette on the fantail. “We could’ve saved so many.”

“Maybe,” Jack said. “Or maybe we just would’ve died somewhere else, a little sooner.”

Carter scowled. “You don’t know that.”

“You don’t either,” Jack said gently. “That’s the point. ‘What if’ is a dangerous game. It only plays nice with people who weren’t there.”

Carter flicked ash over the side. “So you don’t think about it? Not ever?”

Jack looked out at the black Pacific, dotted with phosphorescent glows.

“Every day,” he said. “But not the way you think.”

7. Different Wars, Same Question

In 1962, twenty years after Midway, Jack Hayes sat in a college classroom in California and watched a new generation try to turn war into essays.

He’d taken a teaching job after the war, some combination of guilt and restlessness pushing him into history instead of engineering. He figured if people were going to talk about battles, someone who’d actually been in them ought to have a say.

On the blackboard behind him, in neat chalk script, he’d written:

MIDWAY: TURNING POINT OR MISSED OPPORTUNITY?

Beneath it, three bullet points:

Intelligence vs. Execution

Material vs. Morale

The Weight of “What If”

A young man in the front row raised his hand. His name was Dean. He wore his hair a little longer than Jack liked and a serious expression that reminded Jack of Barker sometimes.

“Yes, Dean,” Jack said.

“I was reading this article,” Dean said, flipping through a notebook. “About how Midway, if we’d won decisively, could’ve shortened the war by a year or more. Saved tens of thousands of lives. Do you think that’s true?”

The words landed like an old song.

“Which article?” Jack asked, more to buy time than anything else.

Dean showed him a magazine. The cover headline shouted:

WHAT IF JAPAN HAD WON MIDWAY? HOW SIX MINUTES ALMOST CHANGED EVERYTHING

Jack didn’t bother hiding his flinch.

“It says here,” Dean continued, “that because we didn’t get that decisive win, we had to slog across the Pacific, island by island. Which meant more casualties. More atomic bombs later. All because of six minutes. Do you think that’s fair?”

The classroom buzzed with interest. Alternate history was in vogue lately. Students liked imagining clean forks in the road where reality had been messy.

Jack tapped the chalk against the board, thinking.

“Fair,” he said slowly, “is not a word I’d use a lot when talking about war.”

Dean frowned. “But is it accurate, then? To say those six minutes ‘almost changed everything’?”

Jack’s mind flashed back to the briefing room, to the argument with the intel officer, to the headline years later that had twisted his story into something he barely recognized.

“I think,” Jack said carefully, “that six minutes did change everything. Just not in the tidy way articles like to lay out.”

“How so?” Dean pressed.

Jack set the chalk down.

“In one version of the world,” he said, “our timing is different at Midway. Our dive bombers roll in just as the Japanese are refueling and rearming. We hit three carriers. Their offensive capacity is gutted. Maybe the war shortens. Maybe it doesn’t. But a lot of naval historians call that the ‘turning point.’”

He gestured at the blackboard.

“In our version,” he continued, “we arrived late. They were ready. We lost ships we couldn’t easily replace. They consolidated at Midway. The war stretched on. We still won, eventually, because we had factories and resources they didn’t. But the road was longer. Bloodier. Different men died.”

“So that proves the point,” Dean said. “Those six minutes mattered.”

“They did,” Jack agreed. “But not because of some neat equation where ‘six minutes’ equals ‘one year of war.’ They mattered because they changed who got to feel like they were on the front foot at a critical moment. They gave the Japanese confidence and us a hard lesson.”

He looked around at the faces watching him.

“The problem,” he said, “is that when we say ‘If only we’d had those six minutes,’ it can sound like we’re blaming the men on the sharp end for not being in the right place at the right time. As if Barker died because he didn’t set his alarm clock right.”

A girl in the back raised her hand. “But isn’t that kind of how strategy works?” she asked. “You look at places where things could’ve gone differently.”

“It is,” Jack said. “And it has value. I’m not saying we shouldn’t analyze. But we need to remember that ‘what if’ is a luxury for people who get to look back. For the people who were there, it can feel like erasing the reality that they did the best they could in the chaos they had.”

Dean frowned, flipping through his notes. “So you don’t like these kinds of articles,” he said. “Alternate history stuff.”

“I don’t like it when they turn battles into board games,” Jack said. “Or when they treat those six minutes like a dial you can just twist without everything else squirming and changing with it.”

A hand went up near the window. “But Professor Hayes,” another student said, “if we don’t ask ‘what if,’ how do we learn?”

Jack smiled, despite himself.

“We should ask it,” he said. “But we should ask it honestly. Not like this—” he tapped the magazine “—with big numbers in the title and a neat conclusion about how one moment would’ve ‘saved’ this many and ‘cost’ that many. We should ask it knowing that any answer we give is built on a thousand assumptions we can’t really prove.”

He paused.

“You want a real ‘what if’?” he asked.

The class leaned forward.

“What if,” Jack said, “instead of just asking how six minutes at Midway could’ve shortened the war, we ask how six minutes of listening to each other now might keep us from needing another Midway at all?”

A groan rose from the back. “That sounds like something from a civics textbook,” one of the boys muttered.

“And yet,” Jack said, “here we are, still building bigger weapons and writing articles about how close we came to using them differently.”

Dean looked down at the magazine, then back at Jack.

“Were you there?” he asked suddenly. “At Midway?”

Whispers rippled. Jack had always been cagey about his personal war stories. He talked about battles in the abstract, about doctrine and decisions, not about what he had done.

“Yeah,” Jack said quietly. “I was there.”

“What was it like?” another student asked.

“Noisy,” Jack said. “Bright. Then very dark. And very, very fast.”

“Do you regret it?” Dean asked. “Like… how it went? Do you wish you’d had those six minutes back?”

Jack hesitated.

He thought about Barker’s grin before the dive. About the argument in the briefing room. About the Japanese flag over Midway. About the men who’d died in 1943 and 1944, men he’d flown with and joked with and written letters home for.

“I regret a lot of things about that day,” he said at last. “I regret that our torpedo boys flew into a meat grinder with hardly any cover. I regret that we didn’t coordinate better. I regret that we weren’t lucky in precisely the way we wanted to be.”

He met Dean’s gaze.

“But do I regret being there?” he asked. “No. Because someone had to be. And do I regret that we didn’t get to live in the neat version of history your magazine laid out? The one where we win big in June and everybody gets home sooner?”

He sighed.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Because I don’t know what version of me comes out of that war. Or if any version does.”

The room was silent.

Jack picked up the magazine and weighed it in his hand.

“You keep reading these,” he told Dean. “You keep asking questions. That’s good. Just… remember that behind every ‘what if’ are people who had to live with the ‘what is.’”

He dropped the magazine on the desk, where it landed with a soft thump.

“Alright,” he said, clapping his hands once. “For next week, I want you to read the primary documents from both sides. Admiral Nimitz’s reports. Admiral Nagumo’s records, what’s left of them. We’re going to talk about the decision-making process, not just the outcome.”

As the students packed up, Dean lingered.

“Professor?” he said.

“Yeah?” Jack asked, stacking his own papers.

“That article,” Dean said, jerking a thumb at the cover. “They quoted a pilot named ‘J.H.’ Who talked about timing and metal and… sounding angry at the way people framed it. Was that you?”

Jack smiled, a little sadly.

“Once upon a time,” he said. “Before I learned that yelling at headlines mostly just gives you a sore throat.”

Dean grinned. “You yelled at the journalist? That’s awesome.”

“It wasn’t my finest moment,” Jack admitted. “But he listened. Eventually. Wrote a better piece later.”

He folded the magazine and slid it into his bag.

“Tell you what,” he said. “If you want to write about Midway, come by office hours. I’ll show you his second article. The one fewer people read, but more people needed.”

Dean nodded. “I’d like that,” he said.

He headed for the door, then turned back.

“Professor?” he said.

“Yeah?”

“I still think six minutes can change everything,” Dean said. “Just… maybe not the way I thought.”

Jack chuckled.

“Me too, kid,” he said. “Me too.”

11. Epilogue: Six Minutes, Everywhere

Years later, long after the last Midway reunion had dwindled from hundreds of veterans to a handful of frail men in wheelchairs, Jack sat alone on a bench overlooking the sea.

The water glittered in the sun, just as it had in 1942. Gulls wheeled overhead, complaining about nothing in particular.

In his lap, he held a small, worn stopwatch.

It wasn’t from the war. It was a retirement gift from his colleagues at the college, an inside joke about his obsession with timing the dive portions of his flying lectures.

But over the years, it had become something else—a physical reminder of those six minutes everyone liked to talk about.

He pressed the crown. The second hand began to sweep.

Tick, tick, tick.

He imagined a different world, one where those ticks had lined up just so on June 4, 1942. Where the clouds parted a little earlier. Where the dive-bombers had found their marks and the carriers had burned.

Would Barker still be alive in that world? Or would fate have found him somewhere else—over Guadalcanal, over Leyte Gulf?

Would the Japanese have surrendered sooner? Later? Differently?

Would someone else be sitting on this bench now, wondering about a different “what if”?

Jack let the stopwatch run for exactly six minutes.

When it hit that mark, he pressed the crown again.

The hand froze.

Six minutes, trapped in brass and glass.

Out on the water, a child laughed. A dog barked. Somewhere behind him, someone dropped a tray, and dishes clattered.

Life went on.

Jack slipped the stopwatch back into his pocket.

“What if Japan had won Midway?” people would keep asking, long after he was gone. “What if those six minutes had gone the other way?”

He’d spent a lifetime with the mirror of that question.

“What if we had won it decisively?” he thought. “What if those six minutes had gone our way?”

In the end, he’d come to understand something he wished he could have explained to that younger version of himself, the angry lieutenant shouting at an intel officer in a hot, crowded briefing room.

The six minutes had mattered.

But not because they’d carried the entire weight of the war on their thin metal shoulders.

They had mattered because they had revealed something about everyone involved—about how they planned, how they reacted, how they learned. About what they valued when the calm cracked open and the world turned to noise.

He patted his pocket, feeling the solid reassurance of the watch.

Maybe that was the real “metal trick” of Midway—not the scrap hung on wires, not the bombs dropped from screaming planes, but the way those minutes had turned cold steel and warm flesh into lessons that would echo for decades.

“Six minutes,” he murmured. “Enough to change everything. Enough to change nothing. Depends on what you do with the rest of your life.”

He stood, joints protesting, and turned away from the sea.

The horizon stayed where it was, indifferent, waiting for the next generation to decide what kind of stories they wanted to pull out of it.

Jack walked back toward the noise and mess and beauty of a world that, for all its flaws, had somehow survived its own worst ideas.

He figured that, in the grand ledger of “what ifs,” that was a pretty good place to end.

THE END

News

How Italian Prisoners of War in Distant American Camps Turned Pennies Into Lifelines, Outsmarted Red Tape, and Kept Their Families Alive Back Home While Officers Argued Over Whether It Was Treason or Mercy

How Italian Prisoners of War in Distant American Camps Turned Pennies Into Lifelines, Outsmarted Red Tape, and Kept Their Families…

How a Battle-Hardened American Sergeant Stunned Surrendered Japanese Soldiers by Handing Them Cigarettes and Chocolate, Sparking a Fierce Argument About Mercy, Revenge, and What It Really Means to Win a War

How a Battle-Hardened American Sergeant Stunned Surrendered Japanese Soldiers by Handing Them Cigarettes and Chocolate, Sparking a Fierce Argument About…

How One Obscure Scout Ship Sent a Single Coded Message That Set the Pearl Harbor Attack in Motion, Was Wiped Out by One Precise Strike, and Left Survivors Arguing for Decades About Who Really Started the Pacific War

How One Obscure Scout Ship Sent a Single Coded Message That Set the Pearl Harbor Attack in Motion, Was Wiped…

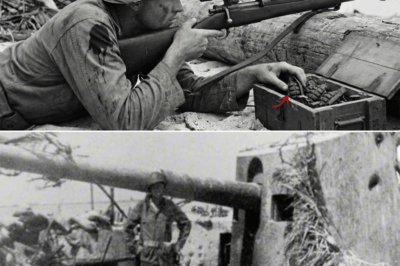

How a Battle-Weary U.S. Sniper Turned a Dead Car Battery into a Week-Long Lifeline, Outsmarted Relentless Enemy Attacks, and Brought His Surrounded Brothers in Arms Home Alive from a Forgotten Island in the Pacific

How a Battle-Weary U.S. Sniper Turned a Dead Car Battery into a Week-Long Lifeline, Outsmarted Relentless Enemy Attacks, and Brought…

The Broken-Sighted Sniper Who Timed a Two-Second Fuse, Silenced Five Jungle Bunkers, and Then Survived Two Days With Shrapnel in His Chest While His Own Side Argued Over What He’d Done

The Broken-Sighted Sniper Who Timed a Two-Second Fuse, Silenced Five Jungle Bunkers, and Then Survived Two Days With Shrapnel in…

How One Exhausted US Infantryman’s Quiet “Reload Trick” Turned a Hopeless Nighttime Ambush Around, Stopped Forty Charging Enemy Soldiers, and Saved More Than One Hundred Ninety Terrified Brothers in Arms on a Jungle Ridge

How One Exhausted US Infantryman’s Quiet “Reload Trick” Turned a Hopeless Nighttime Ambush Around, Stopped Forty Charging Enemy Soldiers, and…

End of content

No more pages to load