When My Grown Daughter Said I Wasn’t Worthy of Her New Family, I Finally Let Go of the Parent Shame Built

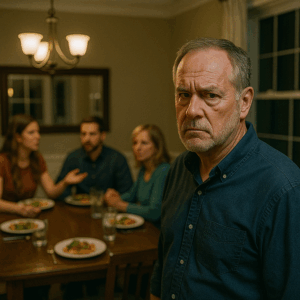

I noticed the knives first.

They were lined up perfectly along the polished oak table—heavy silver, reflecting the low light of the Whitmans’ dining room chandelier. Everything in that house was like that: a little too perfect, like a showroom where no one actually lived.

I sat alone at the far end of the table, in a chair that felt like it had decided I didn’t belong before I even sat down.

At the other end, my daughter laughed at something her new husband whispered in her ear. The sound was light and easy and so unfamiliar that for a second I wondered if I’d gotten the wrong girl.

That couldn’t be my Hannah.

My Hannah had laughed with her whole body, shoulders shaking, hands clapping. This Hannah—this polished, married Hannah in the cream silk blouse and diamonds at her ears—laughed with one hand resting softly on her new husband’s wrist, like she was posing for a photo no one was taking.

His name was Andrew Whitman. Of course it was. The Whitmans were old money in Nashville—country-club rich, lake-house rich, the kind of rich I only saw on TV when the bar in my old neighborhood got stuck on HGTV.

I was the opposite of that.

“Wine, Mr. Cole?” the server asked at my shoulder.

“Just water, thanks,” I said.

My name is Jacob Cole. I’m fifty-four years old, a mechanic in a tire shop, and until three years ago, I was a drunk.

I’ve been sober for 1,126 days.

I counted as the crystal glasses clinked around me, as the Whitmans talked stock options and renovations and which private preschool had the “best pipeline” to some academy whose name I’d never heard before.

I counted because it kept me from counting all the other things:

Days I’d missed school plays.

Nights Hannah had waited for me to show up and I hadn’t.

Times I’d sworn to her I was done drinking and then showed up drunk anyway.

Three years is a long time when you’re measuring sobriety.

It’s also no time at all when you’re measuring damage.

“Jacob.”

I looked up.

Across from me, Margaret Whitman watched me over the rim of her glass. Perfect hair, perfect lipstick, pearls at her throat. She had the vaguely preserved look of wealthy women in their late fifties who’ve made peace with Botox faster than with aging.

“Yes, ma’am?” I said.

I hated that “ma’am” slipped out of my mouth automatically, but there it was. Some habits never leave, even when the booze does.

She smiled. It didn’t reach her eyes. “How’s the chicken?” she asked.

I looked down at the plate I’d barely touched. “It’s good,” I said. “Thank you.”

“That’s Chef Alain’s special,” she said. “He studied in Lyon. I keep telling Hannah that once she and Andrew move into the new house, we’ll loan him out for a few weekends so she doesn’t starve the poor man.”

The table chuckled.

Hannah laughed too, a beat too late.

“I can cook,” she said lightly. “You just never stayed home long enough to taste much, Mom—” She stopped herself, cheeks flushing. “Sorry. Jacob.”

The correction was like a slap I’d paid for.

It wasn’t new. She’d told me three months ago that she wanted to call me by my name. That “Dad” didn’t feel honest.

“I don’t get to rewrite what you remember,” I’d told her then. “You call me whatever feels true.”

I’d meant it.

I just hadn’t realized how much it would sting to hear “Mom” half-said in front of her new family like I was some embarrassing secret.

Margaret’s gaze lingered on me. “So, Jacob,” she said, spearing a piece of roasted potato, “Hannah tells us you’re… in automotive work?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “I’m a mechanic. Cole’s Tire & Auto, over on Murfreesboro Pike. Well. Technically it’s not ‘Cole’s’ anymore. I sold the name when I—” burned my life down “—had some issues. But I still work there.”

I’d planned that sentence better in my head.

Margaret made an understanding face that wasn’t understanding at all. “How nice,” she said. “Good, honest labor.”

Andrew’s father, Richard, cleared his throat. He was a tall man with white hair and the kind of tan people get from golf and boat decks instead of actual labor.

“You said you… sold the business?” he asked. “That must have been hard. I’ve always said, once your name’s on the door, it ought to stay there.”

“It should have,” I said. “I didn’t give it much choice.”

The alcohol had taken care of that. Late invoices, close calls in the shop, the night I’d passed out in the office with the space heater running too hot. My partner—bless him—had bought me out instead of calling the cops, the bank, or my daughter.

Andrew jumped in. “We’re actually thinking about a line of auto-service investments,” he said. “A few franchise opportunities. Dad’s friend is on the board of—”

“Andy,” I said before I could stop myself, “it’s probably not the same as my place.”

He blinked at me. “I’m sorry?”

“The ones you’re talking about,” I said, “you’ve got corporate sending you a manual, training, capital, tech. I had a leased building, a fried coffee maker, and a lift that groaned every time we looked at it.”

A few people chuckled, politely but uncertain.

“It was a good shop,” I added. I didn’t know why I felt the need to say that. Maybe because I’d never really been allowed to say it before without a beer in my hand. “We took care of our neighbors. Made sure no one drove off the lot with brakes that didn’t feel right. That sort of thing.”

“That’s very… salt of the earth,” Margaret said.

She made it sound like “mold under the sink.”

“Mom,” Hannah said sharply.

“What?” Margaret replied, wounded. “It is. We all have our… place in the ecosystem. Not everyone needs an MBA.”

“At least two people at this table sure think everyone does,” their younger son, Brandon, muttered into his wine.

“Brandon,” Richard warned.

Brandon rolled his eyes and went back to his phone.

I wanted to like him on principle.

I glanced back at Hannah.

She caught my eye and looked away quickly, as if my gaze was something that could stain her dress.

My chest tightened.

I’d sat through a lot since she got engaged. Comments about “rough backgrounds” and “different social circles.” Her gently telling me she’d prefer I didn’t give a toast at the wedding because she wanted to “avoid any… unpredictability.”

“I’m not drinking anymore,” I’d said.

“I know,” she said. “But still. You can just… be there. That’ll be enough.”

I’d told myself I was grateful just to be invited.

That had been a year ago.

Now, here I was, at a long table in a house so big it probably had closets bigger than my entire duplex, pretending silverware insulted me less than it did.

I took a sip of water. The condensation dripped down my fingers.

Margaret dabbed her napkin and smiled again. “So,” she said. “Hannah tells us you’ve been very involved in… recovery?”

My fork froze halfway to my mouth.

Hannah’s eyes went wide.

“I didn’t—” she started.

Margaret waved it off. “She didn’t say anything inappropriate,” she said. “We’re not scandalized by addiction in this house, Jacob. We’re past the days of shoving such things in the closet. We’ve had our own… experiences.”

She said “addiction” the way she’d say “termite infestation.”

“That so?” I asked carefully.

Margaret took a sip of wine. “My brother struggled,” she said. “Pills, mostly. He went to rehab in Arizona. Twice. It was… extremely difficult, emotionally and financially. For everyone.”

Richard cleared his throat, clearly not loving this line of conversation. “We prefer to focus on the fact that he’s stable now,” he said. “Gainfully employed. Taking his medication as prescribed.”

I nodded. “Good,” I said. “I’m glad.”

“We believe in support,” Margaret said. “And accountability. The right facilities, the right doctors. Not just… twelve men in folding chairs in a church basement, telling each other war stories.”

The table chuckled again.

I didn’t.

“That’s one way to do it,” I said. “Didn’t work for me. I had to start at the church basement before I believed I deserved anything fancier.”

Hannah inhaled sharply.

Margaret tilted her head. “My understanding is,” she said carefully, “you didn’t actually go to… rehab? That it was more of a… self-directed program?”

I smiled without humor. “That what she told you?”

All eyes slid back to Hannah.

She looked like she wanted to sink under the table. “I said you did AA,” she muttered. “That you go every week.”

“Ah,” Margaret said. “Yes. Well. If that works for you, I suppose that’s… something.”

“It worked well enough that I remember all the last three Christmases’ gifts,” I said. “That’s more than I can say for some years before that.”

Richard forced a laugh. “We all overindulge now and then,” he said. “College was wild for me. Wouldn’t want to be judged on that forever, eh?”

There was an opening there. I could’ve slid into it, made a self-deprecating joke, gone along.

Instead, words came out of my mouth that I hadn’t planned.

“I drove drunk with my kid in the backseat once,” I said quietly. “She fell asleep before we got home. I hit a trash can and told her it was nothing. She was seven. She believed me.”

The table went dead silent.

Hannah stared at me, eyes huge.

“Dad—” she whispered, the word slipping out before she caught it.

I went on anyway. I’d started, and I wasn’t sure I could stop unless I finished.

“I blacked out with a cigarette in my hand twice,” I said. “Once on the couch. Once at the kitchen table. Woke up with a burn on my wrist and a hole in the tablecloth. Could’ve burned the house down. Could’ve killed us both. Didn’t. Pure dumb luck. That’s the ‘war story.’”

I set my fork down carefully.

“You want to talk about ‘overindulging in college,’” I said to Richard, “that’s one thing. What I did was another. You want to judge that forever? Fine. I’ll go first.”

I’d learned in meetings that shame loses some of its hold when you say the worst thing out loud in a fluorescent-lit room.

Apparently, it also shocked wealthy people into silence at dinner.

Margaret blinked rapidly. “Well,” she said slowly, “that’s… very candid.”

Richard coughed. Andrew stared at his plate like it had answers.

Hannah’s hands shook in her lap.

I’d scared her. That wasn’t new. What was new was seeing it from the other side of the monster.

“I’m sober now,” I said. “Not because anyone dragged me to rehab or because a judge threatened me with jail. Because one day I looked at my kid and realized if I didn’t stop, I was going to lose her. Or her life. Or mine. Or all of the above.”

I picked up my water glass. My heart was hammering against my ribs.

“That’s the thing about recovery in church basements,” I added. “No one there believes they’re better than the disease that almost killed them. We all just sit together and try not to die today.”

No one had a snappy reply to that.

Margaret recovered first.

“Well,” she said briskly, “it’s admirable that you’ve… taken responsibility. Truly. Hannah mentioned you’re… stable now. Employed. That’s all we can ask.”

She said “stable” like I was a table they’d tested by leaning gently on.

“I’m trying,” I said. “Every day.”

Silence again.

Then Andrew laughed. Too loud. “So,” he said brightly, fork raised, “how about those Titans, huh?”

Conversation stumbled back to safer topics—football, real estate, next year’s ski trip. I retreated into myself, my words still hanging in the air like smoke.

Maybe I’d said too much.

Maybe I’d said exactly what needed to be said.

I couldn’t tell anymore.

I was debating whether to excuse myself—pretend I had an early shift, claim my stomach hurt—when Margaret set down her dessert fork with a little clink.

“I suppose,” she said, “this is as good a moment as any to discuss what we invited you here to talk about.”

I blinked. “Excuse me?”

Hannah sat up straighter. “Mom, maybe we should—”

“It’s important,” Margaret said, overriding her. “Better to say things clearly so no one misinterprets anything. Don’t you agree, Jacob?”

My stomach dropped.

I knew that tone. I’d heard versions of it from judges, landlords, my ex-wife.

People about to evict you always spoke softly at first.

“Sure,” I said. “Clear is good.”

Margaret folded her hands. The diamonds on her ring flashed.

“As you know,” she said, “Andrew and Hannah just closed on their new home. We’re very proud. It’s a historic property. Made possible by some of the Whitman family resources, and of course by their own hard work.”

“Of course,” I said. “Congrats again.”

Hannah’s eyes begged her mother to stop, but Margaret was in her element now.

“We’re also in the process of updating some… estate arrangements,” she went on. “We’re establishing a family trust for any future grandchildren. Ensuring stability. Generational continuity.”

There it was. The money.

I’d barely gotten used to the idea that my grandchild might grow up sleeping in a nursery with a chandelier. I hadn’t thought much about trusts or college funds or the fact that generational wealth was an entire language I didn’t speak.

“I wanted to be transparent with you, Jacob,” she said, “because Hannah values transparency.”

I almost laughed at that.

“Okay,” I said cautiously. “Transparent about what?”

Margaret glanced at Hannah, then back at me. “We’re establishing certain… expectations for proximity and involvement,” she said. “Physical, emotional, financial. We want to make sure everyone around the children is… aligned.”

“Aligned,” I repeated. “Like tires?”

Brandon snorted into his wine. Andrew kicked him under the table.

Margaret’s smile thinned. “We want to be sure there are no… destabilizing influences,” she clarified. “Especially in the early years. You understand.”

I did. I understood perfectly.

“You mean you want to make sure the drunk doesn’t ruin your grandkids’ play dates,” I said.

“Jacob,” Hannah whispered.

Margaret held up a hand. “I’m not saying that,” she said smoothly. “I’m merely saying that we’d prefer to keep things… consistent. Predictable. As you yourself said, addiction is a chronic condition. Relapses happen.”

“True,” I said. “And wealthy families get DUIs and bury them. Your point?”

“Mom,” Hannah said, voice low, urgent. “Stop. Please.”

“Hannah,” Margaret replied without looking at her, “if you won’t say it, I will. It’s not fair to let him operate under misconceptions.”

Misconceptions about what?

Something heavy settled in my gut.

I turned to my daughter.

“Hannah,” I said, “what is she talking about?”

Her face was pale. Her fingers twisted the napkin in her lap.

“Tell him,” Margaret said.

Hannah swallowed. She looked at Andrew, then at me.

Andrew reached for her hand. She pulled it away.

“Dad,” she began softly, then caught herself. “Jacob. I…”

Her eyes filled with tears.

I felt my pulse pounding in my ears.

“Hannah,” I said gently. “Whatever it is, just say it. I can take it.”

She took a breath.

“At dinner a few months ago,” she said, voice barely above a whisper, “after we left your house, Andrew’s parents asked some questions. About… your history. About when I was a kid.”

I nodded slowly. I could imagine how that went.

“I told them some things,” she said. “About the drinking. About the… the driving. About the time you missed my eighth grade graduation because you were in jail overnight.”

A white-hot flush crawled up my neck. “Okay,” I said. “That’s all… true.”

“I said I forgave you,” she rushed on. “I do forgive you. I do. But when they asked about… about their home, and the baby, and what kind of… influences we wanted around, I… I told them I wasn’t sure.”

Silence pressed around us.

“I told them,” she said, tears spilling over now, “that if it came down to a choice between having you in my life every week and knowing my kids would never see what I saw as a kid, I’d choose them.”

The words hit harder than any punch I’d ever taken.

I sat very still.

My hands felt far away from me.

“Okay,” I said again, but the word sounded wrong in my mouth.

Margaret jumped in, sensing weakness.

“It’s not that we want to cut you out entirely,” she said. “We’re simply… reconfiguring what access looks like. Holidays, perhaps. Larger gatherings. Supervised visits when the children are young.”

“Supervised,” I repeated, my voice dry. “Like the zoo?”

Hannah flinched.

“It’s not like that,” she said quickly. “We just… we think it would be better if… if we created a little bit of… space. For a while.”

“How much space?” I asked. I kept my voice steady by sheer force.

“Enough that the children see you as a… special-occasion person,” Margaret said. “Not a regular, daily presence. Someone they love, but don’t… rely on.”

Someone not at their table.

Someone outside the circle.

There it was.

“It’s not forever,” Hannah said, reaching for me across the table with her eyes, if not her hands. “Just… until they’re older. Until we see… how things go.”

“See if I stay sober long enough to earn my seat,” I said.

No one answered.

My throat burned.

I turned to Andrew. “You good with this?” I asked.

He looked stricken. “It’s not—” he began, then stopped. “We just… want to protect our kids, Mr. Cole. You understand that.”

“I do,” I said. “I understand wanting to protect your kids more than anything in the world.”

My voice shook on the last word.

“Which is why,” Margaret continued briskly, “we thought it would be… helpful to set expectations now. For everyone. So there are no… messy scenes later.”

She glanced at me pointedly.

She meant: no drunken outbursts at birthday parties. No slurred speeches. No broken promises.

The problem was, she was arguing with a ghost.

The man who’d done those things wasn’t at this table.

But his shadow was.

Hannah’s hand crept across the table, stopping halfway.

“Jacob,” she whispered, “please understand. I… I can’t go through that again. I can’t. And I won’t let my kids go through it. I love you, but I—”

She swallowed.

“I need a family that feels… safe,” she finished. “Stable. Worthy of them. Worthy of the life we’re trying to build.”

There.

There was the line.

The one I’d feel for the rest of my life like a scar.

I stared at her.

“At dinner,” I said slowly, hearing my own voice as if from far away, “my daughter tells me I’m not worthy of sitting at the table with her new family.”

She winced. “That’s not—”

“Oh, I heard you,” I said. “I heard every word.”

My hands were steady now.

Too steady.

“Let me say this as clearly as I can, sweetheart,” I said. “I love you. More than I love breathing. More than I ever loved a drink. More than I have loved anything or anyone. That’s the truth.”

Tears spilled down her cheeks.

“But if you honestly believe,” I went on, “that the safest, healthiest thing for you is to keep me at arm’s length to protect your kids from the man I used to be, I’m not going to argue with you at a table full of strangers.”

“Jacob—” she whispered.

“You want space?” I said. “You got it. You’re an adult. You’re allowed to decide who sits at your table.”

I pushed my chair back.

The sound it made on the polished hardwood floor felt louder than it should have.

“Where are you going?” Margaret asked sharply.

“Home,” I said. “You don’t want ‘messy scenes.’ Leaving before dessert is the least messy I know how to be.”

“You’re overreacting,” she said. “This is a calm, rational conversation—”

“It’s a calm, rational rejection,” I said. “Which is somehow worse.”

I looked at Hannah one last time.

She looked broken. Like the little girl who watched me pack a garbage bag with clothes the night her mother kicked me out and asked if it was her fault.

“It was never your fault,” I said, because I needed to say it every chance I got. “None of it. I did those things. I own them. I’ll live with them until I die.”

“I know,” she choked. “That’s why this is—”

“I know why you’re doing it,” I said gently. “You think if you build your new family as far away from where you came from as possible, nothing can hurt it.”

A humorless smile tugged at my mouth.

“But here’s the secret no one tells you,” I said. “Shame eats families from the inside out. Doesn’t matter how pretty the plates are.”

I turned to Richard and Margaret.

“Thank you for dinner,” I said. “The chicken was great. The character assessment, less so.”

Margaret’s lips thinned. Richard looked like a man who’d just realized the wrong guy walked into his meeting.

I walked out of that dining room with every muscle in my body screaming at me to turn back.

To apologize. To beg. To promise things I couldn’t guarantee, like “I will never relapse, ever, not even once, not even if the worst happens.”

Instead, I walked slowly down the long hall lined with family portraits that didn’t have my kid in them, past the foyer where I’d been handed my coat by a man who probably made in tips what I cleared in a week.

My legs carried me down the steps, across the gravel drive, to my twelve-year-old Chevy that coughed when it started.

I put my hands on the wheel and realized I was shaking.

I sat there in the dark, inhaling, exhaling, counting the days since I’d had a drink.

One thousand one hundred twenty-six.

I whispered it out loud like a prayer.

Then I drove home.

Alone.

It would’ve been easy to relapse that night.

Or the next.

Emotionally, the script was there: pushed out, rejected, old wounds ripped open. I could almost feel the muscle memory of turning into the liquor store on the corner, buying the cheapest bottle, that first burn.

But recovery had taught me that we don’t drink at people.

If I drank, it wouldn’t punish Margaret Whitman, or my daughter, or my past.

It would just erase every day I’d crawled and clawed my way through since the last time.

So I didn’t.

I went to my Thursday night meeting instead.

The church basement smelled like coffee and damp carpet and old secrets. The folding chairs were mismatched. The donuts on the table were stale. It was home.

I sat in my usual spot, third from the left, and listened as a new guy named Mike talked about losing his job.

“I thought if I got sober, people would… trust me again,” he said, voice cracking. “Turns out they remember every mistake I made, and I’m stuck walking around in the wreckage, trying not to trip on it.”

Heads nodded around the circle.

I raised my hand.

“Hi, I’m Jacob,” I said. “I’m an alcoholic.”

“Hi, Jacob,” they replied.

“I went to dinner with my daughter’s in-laws last night,” I said. “They’re rich. Like, their silverware has a more impressive résumé than I do.”

A few guys laughed.

“Long story short,” I went on, “she told me that for the sake of her future kids, she wants to… keep some distance. That I’m… not exactly… table material yet.”

I forced a smile.

“It hurt,” I said. “A lot. But I didn’t stop at a bar on the way home. I came here instead.”

“Damn right you did,” Gus grunted. He’d been sober for twenty years and still swore like a sailor.

“What’s messing with me,” I admitted, “is this feeling that no matter what I do, I’ll always be the guy from ten years ago. I can go to every meeting, make every amends, pay every late bill. But in some people’s eyes, I’ll always be the drunk who missed the school play.”

I rubbed my face.

“I don’t know how to live with that,” I said. “And not want to blow it all up.”

An old-timer named Frank leaned forward.

“You don’t live with that alone,” he said. “That’s why we’re here. You come in, you say ‘I’m having a thought that makes the bottle look good again,’ and we say, ‘Cool, pull up a chair.’”

A ripple of agreement went around the circle.

“You can’t force your daughter to trust you,” Frank said. “You can’t AA your way into her heart. That ain’t how it works. But you can keep showing up as the man you are now, not the man she remembers.”

“And if that’s not enough?” I asked.

“Sometimes it ain’t,” he said, blunt. “Sometimes we do all the right things and still lose people. That’s the hardest part. But let me tell you something, kid.”

I was fifty-four; Frank was seventy-eight. He called everyone “kid.”

“The worst day you ever have sober is still better than the best day you had drunk,” he said. “Because at least now, when people hurt you, you actually feel it. You don’t drown it. You feel it, you walk through it, and you come out the other side knowing you didn’t abandon yourself this time.”

The words lodged in my chest.

I didn’t abandon myself.

For most of my life, that had been my default setting.

I went home that night to my tiny duplex with sagging floors and a couch that had seen better years, and I sat at the kitchen table with a legal pad.

I started writing.

Not a letter to Hannah—I’d written those before, in rehab journals and AA step work. Apologies, explanations, promises. This was different.

I wrote:

What I can control:

Whether I go to meetings.

Whether I drink.

Whether I call my sponsor.

Whether I show up when invited.

Whether I show up as the man I am, not the man I was.

Under that, I wrote:

What I can’t control:

Whether my daughter forgives me.

Whether her new family ever accepts me.

Whether I meet my grandkids.

What people think when they hear “alcoholic.”

The past.

The second list was longer. It always was.

I underlined it anyway.

Then, almost without thinking, I flipped to a fresh page and wrote:

What if this isn’t the end of the story?

I didn’t have an answer.

But the question, for the first time, felt worth staying sober to find out.

Six months went by.

I didn’t hear from Hannah.

At first, there were a few texts. Polite, carefully worded.

We need some time.

It’s not about you, it’s about what I can handle.

I love you, I just… need space.

Then, silence.

I saw her life through other people’s screens. Mutual friends posted photos of her baby shower: her hands on her belly, her hair perfect, surrounded by women in pastel dresses. There were balloons and cookies shaped like tiny onesies. Margaret was in the center of every shot.

I wasn’t in any of them.

I went to work. I went to my meetings. I went to sleep. I woke up. I repeated.

Some nights, I sat in my living room and stared at the empty space where a crib could go, where a toy box could sit, where a high chair could stand next to the table.

I imagined a baby with Hannah’s eyes and my stubborn chin.

And I told myself I might never meet them.

And then, one Tuesday afternoon, my phone buzzed while I was up to my elbows in a Toyota engine.

It was a message from an unknown number.

Unknown: Hi. You don’t know me, but I’m Hannah’s friend. My name is Liz. Can we talk?

I wiped my hands on a rag and stared at the screen.

My first thought was, She’s in labor.

My second thought was worse: Something’s wrong.

I stepped outside the bay into the parking lot, the Tennessee sun beating down on the cracked asphalt, and called the number.

A woman answered on the first ring. Her voice was tight.

“Jacob?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “This is Jacob.”

“This is Liz,” she said. “We met once, briefly, at Hannah’s graduation? I brought the banner. You probably don’t remember.”

I did, actually. She’d been the one with the loud laugh and the tattoos her parents pretended not to see.

“What’s going on?” I asked, skipping the small talk. “Is Hannah okay?”

She exhaled shakily. “Physically? Yes. Sort of. Emotionally? No.”

My heart dropped. “What happened?”

“First,” she said, “I need you to promise you’re not going to show up at her house drunk or anything. She’s… fragile. But she needs someone who’s on her side.”

“I haven’t had a drink in three years,” I said sharply. “And I’m not going to break that streak on my kid’s doorstep.”

“Okay,” she said quickly. “Okay. Good. Sorry. I just… I don’t know you. I know… what she’s told me. And most of that is… rough.”

“It is,” I admitted. “And I earned it. Just tell me what’s going on.”

Liz took a breath.

“She had the baby,” she said. “Three weeks ago. A little boy. His name is Noah.”

The name hit me like a physical thing.

“Okay,” I said, because my vocabulary had apparently shrunk to one word. “Is he…?”

“He’s fine,” she said. “He’s perfect. But things in that house are… not.”

She hesitated.

“Andrew’s not handling the baby thing well,” she said finally. “He’s… controlling. He’s always been controlling, but now it’s… worse. Everything has to be his way. The nanny’s way. His parents’ way. There’s a schedule. And if Noah cries off-schedule, he… flips.”

“Flips how?” I asked, my voice low.

“Yells,” she said. “Slams doors. Throws things. Not at the baby. Not yet. But… close. Hannah’s exhausted. She’s recovering from the C-section. She’s not allowed to drive for a few more weeks. And her mother-in-law is there all the time, telling her she’s doing everything wrong.”

I pictured Margaret in someone else’s kitchen, rearranging the bottles on the counter, criticizing the burping technique like she’d invented babies.

“Where’s Margaret now?” I asked.

“Out of town,” Liz said. “Charity gala in Atlanta. She left yesterday. Said she’d ‘given Hannah enough of a head start.’”

There was acid in her voice.

“So Hannah’s alone with Andrew and the baby,” I said.

“And the nanny,” Liz added. “Who reports back to Margaret like she’s the CIA.”

My stomach twisted.

“Why are you calling me?” I asked. The question sounded harsher out loud than in my head. “She doesn’t… want me there.”

“She told you that?” Liz asked.

“She told me she wanted space,” I said. “That she didn’t want me around the kids much. That I wasn’t… table-worthy.”

Liz was quiet for a second. “Yeah,” she said softly. “She told me some of that. But she also told me that when she thinks of ‘safe,’ she thinks of you sober. So.”

The air went out of my lungs.

“She what?” I asked.

“Look,” Liz said. “I’m not going behind her back for fun. I’m doing it because she called me at two this morning sobbing in the bathroom while the baby screamed in the nursery and Andrew stood outside the door yelling that she was ‘making a scene.’ And I realized she had no one in that house who actually thinks of her first.”

I closed my eyes.

“She chose them over me,” I said quietly.

“She chose the life she thought she needed to feel safe,” Liz said. “That’s not the same as choosing them over you. And I think she’s starting to figure that out.”

I swallowed.

“What do you need me to do?” I asked.

“Just… show up,” she said. “Not drunk. Not yelling. Just… be there. You you, not the Before you. I can’t get there until tonight. I live an hour away. You’re closer. I know she said she didn’t want you around but… right now, she needs someone who isn’t on the Whitman payroll.”

My heart pounded.

“Text me the address,” I said. “I’ll be there in twenty minutes.”

The Whitmans’ new house was somehow even bigger than the old one.

It sat on a hill on the outskirts of town, white and symmetrical, with a porch that looked like it had been designed for magazine spreads.

I parked my beat-up Chevy behind a black Escalade and a nanny’s Prius, feeling like a coffee stain on an otherwise perfect tablecloth.

I climbed the steps and rang the bell.

The chime echoed through the house.

No answer.

I shifted my weight, rang again.

After a long moment, the door cracked open.

A young woman in scrubs stood there, hair pulled back, dark circles under her eyes. She looked me up and down.

“Can I help you?” she asked.

“I’m Jacob,” I said. “Hannah’s father.”

Her brows flew up. “Oh. Uh. She’s… resting right now. And Mr. Whitman is—”

She glanced over her shoulder.

I heard shouting, muffled but unmistakable, from somewhere upstairs.

“…I don’t care if he’s hungry, he JUST ate, do you even listen when the pediatrician—”

A baby cried, high and desperate.

My stomach clenched.

The nanny winced.

“I don’t want to cause trouble,” I said. “I just want to make sure my daughter’s okay.”

She hesitated another second, then stepped aside.

“I’ve got five minutes before I’m supposed to start his ‘developmental tummy-time routine,’” she murmured. “Be quick. If Mr. Whitman asks, I didn’t let you in.”

I nodded and slipped past her.

The house was sterile and beautiful. White walls, dark wood floors, tasteful art. It smelled like lemon cleaner and baby powder and something else—stress, maybe.

The shouting got clearer as I climbed the stairs.

“…tired? You’re tired? You’ve been home all day, Hannah, how do you think I feel?”

My chest burned.

The hallway upstairs was lined with framed photos from their wedding: golden-hour light, white dress, smiles so wide they almost looked real.

The door to the nursery was half open.

Andrew stood in the middle of the room, shirt rumpled, face red, rocking a squirming bundle in his arms. He spoke through gritted teeth.

“He’s three weeks old,” he said. “He weighs eight pounds. How are you already failing at this?”

Hannah sat in the glider, tears streaking her face, wearing an oversized T-shirt and leggings. Her hair was in a messy bun, her feet swollen. A bottle sat half-full on the side table.

“I’m not failing,” she said weakly. “He’s just… he’s cluster-feeding. The doctor said—”

“Doctor said, doctor said,” Andrew mimicked. “Doctor also said you should sleep when the baby sleeps, but I see you on your phone all day, crying to your friends about how hard this is. You think my mom cried this much when she had me?”

“Probably,” I said from the doorway. “She just didn’t have Instagram to document it.”

They both froze.

The baby wailed louder.

Andrew turned slowly, eyes blazing. “What the hell are you doing here?” he snapped.

Hannah’s head whipped around.

When she saw me, she burst into fresh sobs.

“Dad,” she whispered, the word ripped out of her like it hurt.

She clapped a hand over her mouth, as if she’d said something forbidden.

Andrew’s face twisted. “The hell did you invite him for?” he demanded. “Is this another one of your little pity parties—”

“I invited myself,” I said calmly. My heart was pounding, but I kept my voice even. “Don’t worry, I didn’t come for the trust fund. I came because someone called me and said my daughter was drowning.”

Andrew scoffed. “She’s not ‘drowning,’ she’s being dramatic,” he said. “She decided she wanted a baby, she got a baby. This is what it looks like. Noise. Work. She doesn’t get to just… tap out.”

“I haven’t tapped out,” Hannah whispered. “I’m right here.”

He ignored her.

“You need to leave,” Andrew said to me, jostling the baby as he jabbed a finger toward the door. “We had an agreement. You get holidays and supervised visits when we say so. This is our home. Our family. You’re not part of this.”

The words should’ve knocked me flat.

Instead, weirdly, they cleared my head.

“I know this is your home,” I said. “I’m not here to move in. I’m here to make sure my daughter and grandson are safe.”

“We’re fine,” he snapped. “Go drink in your truck or something.”

I felt the insult like a slap.

I also heard my sponsor’s voice in my head: You don’t have to pick up everything people throw at you.

“I’m not drinking,” I said. “Haven’t in three years. And I’m not yelling either, even though I really, really want to. That’s growth.”

Andrew laughed, harsh. “You think you get some kind of medal for doing the bare minimum?” he sneered. “Not drinking, not yelling? That’s what normal people do.”

“Normal people don’t scream at exhausted new mothers like they’re employees who missed a deadline,” I said. “Normal people don’t match their voices to the pitch of a crying baby.”

The baby wailed again, almost in agreement.

“Give him to me,” I said.

Andrew blinked. “Excuse me?”

“Give me Noah,” I repeated, holding out my arms. “You’re agitated. He feels that. It’s making it worse. Let me take him for a minute.”

“You’re not touching my son,” Andrew snapped. “You’re a drunk.”

“Recovering alcoholic,” I corrected. “But sure, put that on my nametag.”

I took a step forward.

“Andrew,” Hannah said weakly. “Please. Just let him… help. Just for a minute. My arms hurt. I haven’t slept and—”

“Oh, now you want his help?” Andrew shot back. “The man who missed half your life wants to swoop in and play hero for five minutes and we’re all supposed to clap?”

“I’m not here to play hero,” I said. “I’m here to be a set of steady hands in a room full of shaking ones.”

My own hands trembled a little, but not from withdrawal. From rage.

I stepped closer.

“Look at him,” I said, nodding at the baby. “He’s not a spreadsheet. He’s not a project. He’s a three-week-old human who has no idea what time it is or what the pediatrician said about his eating schedule. He just knows he needs something.”

“And you think you know what that is?” Andrew sneered.

“No,” I said. “But I know what it isn’t. It isn’t you yelling over him.”

Andrew’s jaw clenched.

“You’re not welcome here,” he said, each word clipped. “Hannah, tell him.”

He turned to her.

She sat curled in the glider, arms around herself, eyes huge.

“Hannah,” he repeated, voice low and dangerous. “Tell him he needs to leave. Now.”

Silence stretched.

My heart thudded.

This was it.

This was the moment.

Three years of sobriety. One dinner. A lifetime of damage. All condensed into the space of a breath.

Hannah looked at her husband.

At the red in his cheeks. The tension in his shoulders. The way he gripped the baby a little too tight.

Then she looked at me.

At my calloused hands. My thrift-store jacket. The lines in my face.

“Please,” Andrew hissed. “Tell him. We already talked about this. He’s not—”

“Worthy?” I finished softly.

Hannah flinched.

She closed her eyes.

When she opened them again, something had shifted.

“I told you,” she whispered to Andrew, “that I wanted a family that felt safe.”

“We are safe,” he said. “We have cameras, alarms, a nanny—”

“I don’t feel safe,” she said. Louder this time. “Not when you yell like that. Not when you throw things in the bedroom because the baby puked on your shirt. Not when you walk out in the middle of the night slamming doors while I’m holding him.”

Andrew’s face went pale. Then red.

“You ungrateful—” he started.

“Give me my son,” she said.

Her voice cut through the room like a blade.

Andrew blinked. “What?”

“Give me Noah,” she repeated. “Now.”

He held the baby tighter. “You’re hysterical,” he said. “You’re not thinking straight. This is the hormones talking. My mom said—”

“Your mom’s not here,” Hannah snapped. “I am. Give me my son.”

Her hands shook as she stood. She wobbled a little. I stepped as if to catch her, then forced myself to stop. This was hers.

Andrew hesitated one second too long.

“Andrew,” I said quietly. “If you don’t hand him to her, I’m calling 911 and telling them we’ve got a domestic dispute involving an infant. Then we can all explain ourselves to professionals. In writing.”

He glared at me.

“You don’t get to come in here and threaten me,” he snarled.

“I’m not threatening,” I said. “I’m setting boundaries. There’s a difference. You like those, remember? You used them to keep me away from your table.”

His jaw worked.

For a second, I thought he might actually take a swing at me. Or worse—at the wall. At the crib. At anything near him.

Then, muttering curses under his breath, he thrust the baby toward Hannah.

“Fine,” he spat. “Take him. See how far that gets you when he screams all night and you cry on the floor.”

Hannah took Noah like he was made of glass and miracle.

He calmed almost instantly, like he knew whose arms he was supposed to be in.

She kissed his forehead, tears dripping into his dark hair.

“It gets me further than screaming at him would,” she said quietly.

Andrew laughed once, harsh.

“You called him, didn’t you?” he said. “That’s what this is. You called your pathetic little drunk dad to come save you from the big bad husband. You think that’s going to look good in court if we ever—”

I stepped forward.

“That’s enough,” I said.

He sneered. “Or what? You’ll out-emote me?”

“No,” I said. “I’ll leave. But not before I say this: you don’t get to talk about me like I’m not in the room. Not anymore. I earned that right. Three years. Every day. Every damn meeting.”

I took a breath.

“And you don’t get to talk to my daughter like she’s an employee who failed a performance review,” I added. “She’s not your subordinate. She’s your wife. She just had major surgery and a tiny human ripped out of her. You show some respect.”

Andrew’s eyes flashed. “You ruined her childhood,” he snapped. “You don’t get to lecture me on how to treat her.”

“I ruined a lot,” I said. “I know that. You think I don’t know that? You think I don’t wake up every night with a slideshow of my failures playing in my head? The difference between me and you is, I’m trying to make sure the worst thing Hannah remembers about this family isn’t something that happened last week.”

He opened his mouth.

I held up a hand.

“I’m not staying,” I said. “I’m not moving in. I’m not campaigning for Grandpa of the Year. I’m leaving. Right now. I just needed to see with my own eyes that my daughter wasn’t bleeding on the floor.”

I turned to Hannah.

She clutched Noah close, her whole body curved around him.

Her eyes were huge, wet, and clear.

“I’m going to say this once,” I said, keeping my voice steady. “Then I’m going to walk out, so no one can accuse me of ‘causing a scene.’”

I met her gaze.

“If you want me in your life,” I said, “I will be there. Sober, boring, on time, with snacks. If all you want is a text on your birthday once a year, I’ll do that too. If you decide I’m too much, or not enough, and you need to cut me off for good, I’ll respect it. Not because I think I deserve banishment forever, but because boundaries are important, and I refuse to be the man who tramples yours again.”

Tears spilled down her cheeks.

“But don’t you ever again,” I added gently, “say that I’m not worthy of sitting at your table like I’m a dog under it. Not after the work I’ve done. Not after the work I’m still doing. You can choose distance without turning me into a monster to make it easier.”

She nodded, sobbing.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry. I was… scared. And ashamed. And I thought if I made you the villain, I wouldn’t have to look at how I’m letting them control me.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s not okay,” I corrected, “but it’s understandable. And it’s fixable. If you want it to be.”

Andrew scoffed. “This is insane,” he said. “You’re all insane. You want to run back to Daddy the Drunk, go ahead. See how far that gets you when the checks stop coming—”

“Checks,” I murmured. “Right.”

I looked at Hannah.

“Whose checks are paying for this house?” I asked. “You two? Or his parents?”

Hannah swallowed. “Mostly… theirs,” she admitted. “They… co-signed.”

“And the baby expenses?” I asked.

“The Whitman Family Trust,” Andrew said proudly. “Smart planning. You wouldn’t understand.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine using money as a leash and calling it love.”

He glared at me.

I sighed.

“I’m leaving now,” I said. “I’m going to go downstairs, thank the nanny, and drive back to my life. I’m not going to drink about this. I’m going to call my sponsor and probably cry in my car for a while. That’s my plan.”

I nodded at Hannah.

“If you want out of here,” I added quietly, “you call me. I won’t judge. I won’t say ‘I told you so.’ I’ll just show up with my crappy Chevy and some cardboard boxes. Or I’ll pay for a Lyft if I have to. You won’t be alone.”

She clutched Noah tighter and nodded.

“Okay,” she whispered. “Okay.”

Andrew laughed. “You think she’s going to leave me?” he scoffed. “And go where? Your place? You think Margaret’s going to stand for that? She’ll cut her off. She’ll cut the baby off. You’ll lose everything, Hannah. The house, the money, the—”

“We,” Hannah interrupted softly.

“What?” Andrew snapped.

“We’ll lose everything,” she said. “You keep saying ‘she,’ like I’m the only one tied to your parents’ money. But if your mom cuts me off, she cuts you off too. That’s what she threatened, remember? ‘You marry beneath you, you live beneath you.’ Those were her words.”

His face drained of color.

“So maybe,” Hannah went on, voice gaining strength, “we both need to figure out who we are without her checkbook. Because I’m starting to think the only way my son is going to know what ‘safe family’ feels like is if we stop letting them buy the right to treat us like children.”

Silence filled the room.

Noah hiccupped.

Andrew stared at her like he’d never seen her before.

“You’re tired,” he said finally. “You’re not thinking clearly.”

“I’m exhausted,” she agreed. “Which is when the truth usually slips out.”

He looked between us, jaw tight.

“This isn’t over,” he said.

He stormed out, slamming the nursery door so hard that a framed print of woodland animals shook on the wall.

Noah startled but didn’t cry.

Hannah sagged into the glider, clutching him.

I stood there, hands at my sides, heart pounding.

“You okay?” I asked her.

She laughed weakly through her tears. “Define ‘okay.’”

“Not actively bleeding, not actively drunk, not actively incarcerated,” I said. “That’s the bar we use in my meetings.”

She huffed a laugh that turned into a sob.

“I’m so sorry,” she whispered. “For that dinner. For saying you weren’t worthy. For letting them talk about you like you were… some charity case. I was just so ashamed.”

“Ashamed of what?” I asked. “Me?”

Her shoulders shook.

“Ashamed of where I came from,” she admitted. “Of having a dad who… who missed things, and went to jail, and sold his business. I thought if I didn’t talk about it, it would… go away. And when I did talk about it, I made it sound worse so I wouldn’t have to admit I still loved you.”

The confession gutted me.

“You don’t have to apologize for wanting distance from the man I was,” I said softly. “He was a piece of work. I wouldn’t invite him to my table either.”

She looked up at me, eyes red-rimmed.

“But I do think you owe the man I am now a… second look,” I added, trying to keep my voice light. “Maybe a cup of coffee. Eventually.”

She laughed, a wet, broken sound.

“I’d like that,” she said. “I don’t know what… any of this will look like. With Andrew. With his parents. With… the trust. But I know I don’t want my son growing up thinking money is what makes people worthy of love.”

“Good,” I said. “Because I don’t have much.”

She rolled her eyes, sniffling. “You have more than you think.”

I reached out, slowly.

“May I?” I asked, nodding at Noah.

She hesitated only a second, then nodded.

I took him in my arms.

He was so small.

Warm and wriggling and perfect.

He blinked up at me with unfocused eyes, his tiny mouth working on the air.

“Hey, little man,” I whispered. “I’m your grandpa. I’m kind of a mess, but I’m working on it.”

He curled his fingers around my pinky. The grip was surprisingly strong.

Hannah watched us, tears streaming down her face.

“Do you think,” she said softly, “we could… start over? Not from scratch. That’s impossible. But from here. From this room. This version of you. This version of me.”

I looked at her.

At the exhausted, fierce woman she’d become. At the little girl who still lived behind her eyes.

“We can start from every day we both wake up and decide we’re willing to try again,” I said. “That’s how I do it with the bottle. Might as well use it everywhere else.”

She nodded.

“I can’t promise I won’t mess up,” she said. “Say the wrong thing. Pull back when I’m scared.”

“I can’t promise I won’t do the same,” I said. “But I can promise you this: I won’t hide in a bar when it happens. I’ll be right here. At whatever table you’ll have me.”

She smiled through her tears.

“Then,” she said, “I guess we need a new table.”

It didn’t happen overnight.

Nothing worth keeping ever does.

Hannah didn’t leave Andrew that day. Or that week. She did, however, insist he go to therapy. She went with him, then alone.

She started coming to Al-Anon, sitting quietly in the back at first, then speaking up.

“I thought ‘addict’ meant ‘bad person,’” she said one night. “Now I know it means ‘sick person who hurt me.’ The hurt is still real. The sickness doesn’t excuse it. But it explains a lot.”

She didn’t move out when Margaret threatened to cut them off. Not yet. But she stopped letting her mother-in-law dictate every feeding, every nap, every outfit.

“No, Mom, we’re not doing the nanny cam in the nursery,” she said on the phone one afternoon with me sitting at the kitchen island in my duplex, Noah in a portable crib next to me. “If you want to see him, you can come over like a normal grandma.”

She and Andrew fought. A lot.

Sometimes he stormed out.

Sometimes she did.

One particularly bad night, she called me from her car, sobbing.

“I’m parked outside a Walgreens,” she choked. “I don’t even know how I got here. I just… drove. I feel like I’m thirteen again, hiding in my room with my headphones on while you and Mom screamed.”

The guilt hit me like a wave.

“It’s not the same,” I said quickly. “It’s not. But if your body thinks it is, that’s real. That’s trauma. Not drama.”

“What do I do?” she whispered.

“Drive here,” I said. “I’ll make coffee. You can cry on my couch. Or not. You can sit in silence and watch whatever dumb show is on. You don’t have to decide anything tonight.”

She came.

She fell asleep on my couch with Noah on her chest, both of them breathing in sync.

I sat in the armchair and watched them like they were the last two people on Earth.

I didn’t pick up my phone.

I didn’t pace.

I didn’t drink.

I just… stayed.

Over time, Andrew changed too.

Slowly.

He went to counseling. He took a hard look at his own parents’ brand of “love.” He started saying things like, “I don’t know how to handle this; can we figure it out together?” instead of barked orders.

He apologized to me. Not in a grand, cinematic way. In the awkward, grudging way of a man who’d never had to admit he was wrong in his life.

“I still don’t… get it,” he said one afternoon, watching Hannah hand Noah to me at a park. “The whole… meeting thing. God thing. Whatever. But she’s… different. You’re… different. I’d rather have this version of you around than the ghost she used to talk about.”

“That ghost was a lot thinner and had more hair,” I said. “But yeah. Me too.”

We laughed.

Margaret never really warmed to me.

She showed up when she felt like it. She made comments. She wrinkled her nose at my truck.

But she stopped calling me “pity.” Stopped saying “that man” like I was an infection.

Once, when she thought no one was listening, I heard her say to a friend on the phone, “Well, at least he’s sober. It’s more than I can say for my brother.”

It wasn’t much.

But it was something.

The real changes happened at smaller tables.

A breakfast nook in my duplex, where Hannah and I spread out Noah’s toys and drank coffee while he pounded Cheerios into the high chair tray.

A sticky diner table where I met her halfway between my place and hers so we could talk without anyone hovering.

The folding table in the church basement, where she once brought Noah to a holiday potluck and watched a bunch of old drunks coo over him like he was the first baby they’d ever seen.

“This is my daughter, Hannah,” I told them. “And this is my grandson, whose college fund will be funded entirely by baked goods and guilt tripping.”

They laughed.

Hannah blushed, but she smiled.

“Hi,” she said. “Thanks for… taking care of my dad.”

Frank waved a hand. “He takes care of us as much as we take care of him,” he said. “That’s how it works. Everyone’s broken. Everyone sweeps.”

On Noah’s first birthday, we had two parties.

One at the Whitmans’ house—catered, themed, with a smash cake and a professional photographer.

One at my duplex—homemade cupcakes, mismatched plates, Noah sitting on the floor in a dinosaur onesie while my neighbors passed him around like a sack of precious flour.

At the Whitmans’, Margaret presented him with a monogrammed train set and a college fund certificate.

At mine, I gave him a small stuffed bear wearing a T-shirt that said “Papa’s Buddy” in crooked letters I’d ironed on myself.

He ignored both and chewed on a wooden spoon.

After everyone left, Hannah stayed.

She sat at my tiny kitchen table, knees bumping against mine, Noah asleep in the pack ’n play in the living room.

She looked around at the peeling linoleum, the thrift-store chairs, the plant I kept forgetting to water.

“Do you ever wish you’d had something like… what Andrew had?” she asked. “Growing up. Big houses. Nannies. Trusts.”

I thought about it.

About what that kind of money could’ve done for us. For me. For my mother. For my liver.

“For a long time, yeah,” I admitted. “I thought if I’d grown up with that, maybe I wouldn’t have ended up at the bottom of a bottle. But then I look at Andrew, and Margaret, and the way they love each other with contracts and conditions, and I’m not so sure.”

She smiled faintly.

“I think every family has their own… disease,” I said. “Ours was booze and silence. Yours and Andrew’s was control and money. Noah’s doesn’t have to be either of those.”

She nodded slowly.

“He’s going to grow up at a lot of tables,” I said. “Yours, mine, theirs. He’s going to hear a lot of stories about where he comes from. Some will make him proud. Some will make him flinch. That’s life.”

I took a breath.

“All I want,” I said, “is for him to know that wherever he is, whatever he’s done, there’s at least one table he can always pull up a chair to without asking if he’s worthy first.”

She reached across the table and took my hand.

“There’ll be two,” she said.

We sat there, hands clasped, listening to Noah’s soft snores through the doorway.

I thought about that night at the Whitmans’ long table, when my daughter had told me I wasn’t worthy of sitting with her new family.

I realized then that I’d spent half my life begging for a seat at other people’s tables—my ex-wife’s, my boss’s, the world’s.

I’d spent the other half flipping those tables when they didn’t give me what I wanted.

Now, for the first time, I was building my own.

It wasn’t as shiny.

The chairs wobbled sometimes.

The plates were chipped.

But the people at it didn’t have to meet a quota of perfection or a net worth minimum to sit.

They just had to be willing to show up as who they were that day.

Messy.

In progress.

Trying.

“Dad?” Hannah said.

I looked up.

The word hung in the air between us, fragile and miraculous.

She flushed. “Sorry,” she said quickly. “I mean. Jacob. I know we said—”

My throat tightened.

“You can call me whatever feels true,” I said, like I had that first time. “If that changes day to day, I’ll roll with it.”

She smiled.

“Okay,” she said. “Dad.”

Something in my chest loosened.

I exhaled.

“Okay,” I echoed. “Kiddo.”

We sat there in our mismatched chairs, in a little kitchen that smelled like coffee and cheap takeout and redemption, and I realized something simple and enormous:

Worthiness isn’t something other people hand you with a side of judgment and crystal stemware.

It’s something you claim for yourself, quietly, every day you choose not to abandon who you’re becoming.

The rest—who invites you to brunch, who writes you into a will, who decides you’re “family material”—that’s just noise.

The real work is staying sober enough, present enough, stubborn enough to be ready when the people who matter finally look up and say, “Can we start again?”

And to say, with your feet planted on the ground and your hands steady on the table you built:

“Yeah. Pull up a chair.”

THE END

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load