Ten Years They Called Me a Whore, Until Three Black Cars Arrived and an Old Man Fell to His Knees Outside My Broken Porch

The summer I turned thirty-two, the town finally ran out of new names to call me.

They’d tried them all over the last ten years—whore, homewrecker, trash, “that Miller girl who spread her legs and doesn’t even know who the father is.” Somewhere along the way, I stopped flinching. You get called a thing enough times, it starts to sound less like an insult and more like a job title.

Maple Ridge was one of those little Midwestern towns you pass on the highway without noticing. Two stoplights, one Dairy Queen, a faded Walmart a few exits away. Folks there believed in Jesus, high school football, and the fact that everyone’s business was a communal sport.

I was everybody’s favorite sport.

They whispered it in the church parking lot.

They hissed it in the aisles at Dollar General.

They said it to their kids under their breath—“Don’t stare at her, honey, she made bad choices”—like irresponsibility was contagious.

What hurt more than any of that wasn’t the names they called me.

It was the name they gave my boy.

“Orphan.”

They didn’t mean it in the technical sense. I was right there. But when your father is a question mark and your mother is a scandal, I guess in their minds you’re halfway to being nobody’s.

Only, my son, Noah, was very much somebody’s.

He was mine.

And on the afternoon everything changed, he was sitting at our wobbly kitchen table, chewing the eraser on his pencil and squinting at a sheet of math homework.

“Mom,” he groaned, “what’s the point of fractions? Nobody uses fractions in real life. When have you ever needed to know three-fourths of something?”

I snorted, rinsing out the coffee pot in the sink.

“I need to know three-fourths of my paycheck goes to bills,” I said. “And the other one-fourth tries to keep you in shoes that fit those clown feet.”

He looked down at his sneakers, the toes worn thin.

“They’re not that big,” he muttered.

“They’re enormous,” I said fondly. “You’re going to be six-two like your—”

I stopped myself.

Like your father.

Noah noticed. He always did.

His pencil stilled. “Like who?”

“Like a mailman,” I said quickly. “They do a lot of walking.”

He rolled his eyes. “Smooth save, Mom.”

“Just do your fractions,” I said.

He bent back over the page, tongue peeking out of the corner of his mouth the way it always did when he was concentrating. His hair—a wavy, stubborn brown—fell into his eyes. I made a mental note to cut it that weekend. Add it to the list with “oil change” and “fix the leak under the sink” and “find a new second job that doesn’t require standing on your feet ten hours.”

The kitchen clock ticked.

The fridge hummed.

Outside, the August heat pressed against the thin walls of the house like a hand.

Our place sat at the far edge of town, where the potholes got bigger and the streetlights got farther apart. Peeling paint, a porch with a sag in the middle, a yard more weeds than grass. I’d inherited it when my parents died—the only thing they’d had to leave—and it was both our refuge and our prison.

I had just set the coffee pot back on its base when the sound of engines rolled up the road.

Not a pickup.

Not the growl of somebody’s muffler about to fall off.

Something…cleaner. Thicker. A low, expensive purr.

Noah’s pencil stopped again.

“You hear that?” he asked.

I did.

And then I saw it.

From the kitchen window, I watched three black cars glide slowly up our cracked street—sleek, shiny sedans that looked like they’d gotten lost on their way to a senator’s fundraiser.

They stopped in front of our house.

Directly in front.

My first thought was that somebody important had died and the funeral procession had gotten very, very off course.

My second was that maybe this was some kind of scam. Jehovah’s Witnesses really leveling up.

My third was that it didn’t matter who it was; if they were here, it meant neighbors would be peeking through blinds, seeing my address associated with something fancy, and by morning there’d be fifty new theories at the diner.

“Mom,” Noah whispered, “are we in trouble?”

The impulse to say always was strong.

Instead, I wiped my hands on a dish towel and squared my shoulders.

“Stay here,” I told him. “And if they look like they’re selling timeshares, hide.”

He snorted a little, but his eyes were wide.

I stepped out onto the porch.

Immediately, I wished I’d at least been wearing something other than my oldest jean shorts and a tank top with a salsa stain.

The August air hit me like a hair dryer. The smell of hot asphalt and magnolia and cut grass all jumbled together.

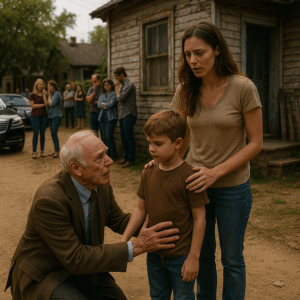

The first car’s back door opened.

The man who stepped out looked like he’d been born in a boardroom and never once set foot on a street like ours.

Tailored gray suit. White hair combed back from a face deeply lined, but not in the soft, plump way of old men who spent their last decades in recliners. These lines looked carved by wind and worry.

He put one hand on the edge of the door, like he needed a second to gather himself before standing fully.

The drivers from the other cars got out too, big guys in black, scanning the street like my neighbor’s yapping Chihuahua was a threat.

For a brief, surreal moment, I wondered if I was dreaming.

Then the old man’s eyes lifted.

Our gazes met across the patchy yard.

Whatever composure he’d had shattered.

His hand flew to his mouth.

“Oh my God,” he whispered, voice cracking. “You…you have his eyes.”

I blinked.

I’d been called plenty of things in my life. Beautiful wasn’t usually one of them. But the way he was looking at me wasn’t about me. It was like he was looking through me, at something only he could see.

“Can I help you?” I called, cheeks flushing.

He took a halting step forward.

“You’re Grace?” he asked. “Grace Miller?”

On any other day, I would’ve lied. Said no. Said I was just the housekeeper. Said I was whoever I needed to be to avoid whatever mess this was.

But something in his voice—a trembling urgency—made me nod.

“Yeah,” I said slowly. “That’s me.”

He exhaled like he’d been holding his breath for years.

And then, right there on my dirt patch of a front yard, he dropped to his knees.

The drivers moved, alarmed, but he waved them off.

“I’ve finally found him,” the old man said, looking up at me, eyes luminous with something like…hope? Grief? Both? “I’ve finally found my grandson.”

Behind me, the screen door creaked.

Noah’s shadow appeared at my elbow.

“Mom?” he said. “What’s going on?”

The old man’s head jerked toward him as if yanked by a string.

His mouth fell open.

I watched as his eyes traveled from Noah’s messy hair to his freckled nose to the stubborn angle of his jaw.

I knew what he was seeing.

He was seeing a ghost.

Because I saw him too sometimes, when Noah’s asleep face relaxed in just that way.

The old man’s hand lifted, shaking, then dropped.

“He looks just like Ethan,” he whispered.

Every nerve in my body lit up.

The yard, the cars, the heat, the whole world narrowed down to that one name, spoken in that voice.

“Say that again,” I said, my voice very, very calm.

Please let me have misheard. Please let this not be real.

“Ethan,” the old man repeated. “My son. Ethan Hale. You…you knew him, didn’t you?”

The dish towel slipped from my fingers.

I hadn’t heard that name spoken out loud in ten years.

Not by anyone but me.

Not since the night he’d driven out of town with my heart in his trunk.

The summer I turned twenty-two, Maple Ridge finally felt too small to hold my dreams and my loneliness at the same time.

It was the year the factory closed and took half the town’s paychecks with it. People drove farther for work. Foreclosures popped up like dandelions on every street.

I worked days at the elementary school office and nights waiting tables at Deacon’s Diner, where the neon sign buzzed whether it was on or not and the coffee was older than most of the waitstaff.

That was where I met him.

Ethan came in one Saturday afternoon, dust on his boots, a map crumpled in his hand. His pickup had Texas plates, his eyes were this impossible shade of green, and his smile…his smile was the first thing in years that made my lungs forget how to breathe.

“Y’all got pie?” he’d asked, sliding into a booth like he’d been sitting in Deacon’s his whole life.

“We have substance flavored like pie,” I’d said. “Cherry or apple. Apple’s fresher.”

He’d laughed, the sound warm and surprised.

“Apple it is,” he said. “Surprise me with the rest.”

I’d brought him coffee and meatloaf and listened as he told me he was just passing through, chasing jobs building wind farms, laying pipelines, whatever paid.

I told him about my town. My parents. My half-finished associate’s degree I couldn’t afford to finish.

He came back the next day.

And the next.

For a month, he was as regular as the sunrise.

We drove out to the lake, drank cheap beer in the bed of his truck, talked about the places we wanted to see. He told me stories about Dallas highways and Austin bars and parents who loved him but loved their money more.

He never said “I love you.”

But he held me like he might.

When I found out I was pregnant, he was already gone.

He’d gotten a call, said there was a job in Oklahoma that paid double.

“I’ll send for you,” he’d said, kissing my forehead. “Soon as I’m settled. You won’t be stuck in this place forever, Grace. I promise.”

He’d loaded up his pickup and driven away, dust swirling in his wake.

He never sent for me.

He never sent anything.

No calls.

No letters.

No trace.

I waited three months.

I wrote to the P.O. box address on the crumpled card he’d left in my glove compartment.

The letter came back: Undeliverable.

I tried his cell. Disconnected.

I told myself he’d lost my number. That he’d written and I’d missed it. That something had happened.

And then my belly grew. And the town noticed.

By the time Noah was kicking my ribs, the story had taken shape.

I was a whore.

He was “some drifter.”

And because I didn’t have a ring or a husband or a believable lie, that was that.

The night I went into labor, it was just me and a nurse named Stephanie who held my hand and said, “You can do this, girl. You don’t need anybody.”

I had done it.

For a decade.

And now an old man in a suit was kneeling in my yard, saying Ethan’s name like it was the only word he remembered.

My heart hammered.

“You knew Ethan?” I said, forcing my voice to stay low. “What are you, his lawyer?”

The old man flinched as if I’d slapped him.

“I’m his father,” he said.

The world tilted.

Noah took a step closer to me, his shoulder pressing against my arm.

I could feel the neighbors watching from behind their curtains, their eyes burning holes in my front door.

“Ethan’s father,” I repeated numbly.

“Yes,” he said. “My name is Walter Hale. I’ve been looking for you for a very long time.”

His gaze shifted to Noah again.

“For both of you,” he added softly.

Noah’s fingers curled into the hem of my tank top.

“Mom,” he whispered, “who is this?”

I swallowed.

“He says he’s your grandfather,” I said.

The word felt foreign in my mouth. Heavy.

Noah’s eyes widened.

“You mean like…Grandpa?” he asked. “Like in cartoons?”

He’d never had one. My parents had both died before he was born. His father’s side of the family was a blank space. I’d always told myself I didn’t want them. That they hadn’t exactly come looking.

Now, one of them was on his knees in my dirt.

I folded my arms, feeling the sun beat on the back of my neck.

“I think you ought to stand up,” I told Walter. “You’re going to ruin those fancy pants.”

He let out a breathy laugh, pushed himself shakily to his feet with the help of one of his guys.

Up close, he looked even more tired. There were dark circles under his eyes, like he hadn’t slept in years.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to…startle you. I just—seeing him…” His voice broke. “It was like seeing my son again. The night before—”

He cut himself off.

I latched onto that.

“The night before what?” I demanded.

He looked me in the eye.

“The night before Ethan died,” he said.

Something inside me snapped.

“Died,” I repeated. “Ethan is…dead.”

“Yes,” Walter said quietly. “He died in a car accident nine years ago. He never came home. Not to Dallas, not to anywhere. We looked for him for months. When we found the truck…there wasn’t much left.”

The yard blurred around the edges.

I heard Noah’s sharp inhale.

“So all this time…” I said slowly, “you thought he was dead, and I thought he’d left us.”

“We didn’t know about you,” Walter said. “We didn’t know about—” He gestured helplessly toward Noah. “Him.”

“Funny,” I said, my voice going cold. “Because I wrote to you.”

He frowned. “You…what?”

“In Dallas,” I said. “To Hale Construction. To Hale Enterprises. Whatever name was on the card in his wallet that night at the lake. I wrote that I was pregnant. That I needed to talk to him. The letters came back. Address unknown.”

For the first time, Walter looked…unsure.

He glanced back at one of his men, a younger guy with a sharp haircut and a tablet tucked under his arm.

“Is that possible?” Walter asked him. “Could something sent to the office have been returned?”

“If it was addressed wrong,” the younger man said, shrugging. “Or if somebody…intercepted it.”

“Intercepted,” I repeated. “That a thing rich people do?”

Walter winced.

“I believe you,” he said. “I believe you wrote. I believe my son never got those letters. He—he always said if he ever messed up bad enough to get a woman pregnant and not marry her, I’d never see him again.” He swallowed. “I told him I’d disown him. He thought I meant it. Maybe that’s why he never told me about you. But when he died, I…” His voice broke again. “I would have taken any piece of him I could get.”

I’d spent ten years building anger around the hole Ethan left.

This wasn’t how I’d pictured it shattering.

“Why now?” I asked. “If you didn’t know, and then he died, and it’s been nine years…why show up today with your parade of cars?”

He straightened a little, like he was bracing himself.

“Because I found this,” he said.

He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a worn photograph.

He held it out with shaking fingers.

My own face stared back at me.

Younger. Hair down. Grinning at the camera over the hood of Ethan’s truck. The night at the lake.

On the back, in Ethan’s messy scrawl: Grace – Maple Ridge. Don’t lose her, idiot.

My knees almost gave.

“I found it last month,” Walter said softly. “In a box in the back of our storage unit. It must’ve gotten mixed in with his things when we…put away what was left. I turned it over, saw the name of the town. For the first time, I had something more than just ‘somewhere up north.’”

His eyes met mine.

“I got on a plane,” he said. “And I’ve been knocking on doors for three weeks, asking if anyone knew a ‘Grace from ten years ago.’”

“People know me,” I said, bitter. “They just don’t use my name.”

A flash of anger crossed his face.

“Yes,” he said. “I gathered that.”

Of course he had.

Maple Ridge gossip traveled faster than the internet.

“You show up in a line of black cars on the wrong side of town,” I said. “You bet they’re talking.”

Walter took a breath.

“I know this is…a lot,” he said. “I didn’t come here to drag him away from you, Ms. Miller. I came to ask if I could know him. If he could know he has family. That the things they say about you are lies.”

The word hung between us.

Lies.

Nobody had said that word about me in a long time, at least not in my defense.

From behind his leg, Noah whispered, “Mom?”

I looked down.

His eyes were huge.

“You knew my dad,” he said to Walter. “For real.”

“Yes,” Walter said. “He was my son. My only child.”

“You’re rich,” Noah said bluntly, eyeing the cars.

“Noah,” I muttered.

Walter actually smiled.

“I’ve done…well,” he admitted. “I started a construction company when I was nineteen. Built it into something bigger than I ever dreamed. But that doesn’t matter right now.”

“If it doesn’t matter,” I said, “why’d you bring the entourage?”

He glanced back at the cars.

“This is…how I travel,” he said. “Habits.” He turned back to me. “I can send them away.”

He snapped his fingers.

The drivers got back in the cars, pulled down the street a bit, giving us space.

It was just the three of us in the yard now.

Four, if you counted the ghost between us.

I ran my hands through my hair.

“Okay,” I said. “Say I believe you. Say you’re really who you say you are. What next? You think you can just walk up, say ‘grandson,’ and everyone lives happily ever after?”

“Grace,” he said gently, “I’m not naïve. I know I can’t make up for ten years with one visit. But I can start. I can—”

“Buy him things?” I snapped. “Pay off the years you weren’t here? Write a check and make the town forget they called me a whore?”

His jaw clenched.

“No,” he said. “I can’t make them forget. But I can make them regret it.”

Our eyes locked.

My heart pounded.

Behind me, the screen door creaked again.

My neighbor, Mrs. Cline, stood on her porch in her housecoat, pretending to water her dead petunias while blatantly staring.

Her gaze met mine.

Once, that would’ve made me shrink.

Now, with the old man’s photograph burning my fingertips and my son pressed to my side, something in me flared.

“Get inside, Noah,” I murmured. “I need a minute with…with your grandfather.”

Noah’s hand tightened.

“I wanna stay,” he whispered.

“You’ll be in the window,” I said. “You’ll see everything. I promise.”

He studied my face, then nodded slowly.

“Okay,” he said. “But if he tries to kidnap you, I’m calling 911.”

Walter choked on what sounded like a laugh and a sob.

“I’ll be right here,” I said.

Noah slipped back inside.

The old man watched him go like a man starving watches someone take away his last bite of food.

When the door closed, he turned back to me.

“Grace,” he said, “I know you have every reason to hate me. My son left. My family didn’t come looking. Your town made you their villain. I can’t change the past. But I can offer you something now.”

“Offer,” I echoed. “There it is. The pitch.”

He didn’t deny it.

“I want to bring you both to Dallas,” he said. “To meet his grandmother—my wife, Catherine. To meet your son’s cousins, aunts, uncles. To give him opportunities I know you’ve been breaking your back trying to give on your own.”

I barked a humorless laugh.

“You don’t know anything about what I’ve been trying,” I said.

He looked at my hands. Callused from typing, from lifting, from scrubbing. At the worn flip-flops. The chipped paint on the porch.

“I know enough,” he said quietly.

I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “You know nothing. You say you’ve been here three weeks? In this town? Then you’ve heard the stories. You know what they say about me and about him. You waited ten years. You can wait a bit longer.”

His shoulders sagged.

“What are you saying?” he asked.

“I’m saying,” I said, “if you want to know my son, you start here. Not in your big fancy house. You come back tomorrow. Alone. No cars that cost more than my mortgage. We talk. We figure out…what this even is. And you do not go behind my back to the school or the pastor or anybody else until I say so. Got it?”

To my surprise, the corner of his mouth lifted.

“You remind me of my mother,” he said. “Mean as a snake when she had to be.”

“Good,” I said. “I grew up with enough men who thought they could bulldoze women with money. I don’t need another.”

He nodded.

“I’ll come back tomorrow,” he said. “Alone. Noon?”

“After school,” I said. “Noon is lunch duty.”

He blinked.

“You work at the school?” he asked.

“Front office,” I said. “Somebody has to buzz in the weirdos and copy worksheets.”

He smiled faintly.

“I’ll see you at three,” he said.

He turned to go, then hesitated.

“Grace?”

“What.”

“Thank you,” he said softly. “For taking such good care of my grandson.”

I didn’t answer.

I watched him walk back to the car, my chest tight, my mind spinning, my past and present colliding like cars on ice.

The people in town had finally gotten what they wanted.

Something big was happening at the Miller house.

Only, this time, I wasn’t going to let them tell the story for me.

By sundown, Maple Ridge was on fire.

Not literally. We weren’t that dramatic.

But the phones were.

Sylvia called first, of course.

She’d been my best friend since we were thirteen and had simultaneously gotten braces and broken hearts.

“Okay,” she said without preamble, “you get three questions to guess what people are saying at Deacon’s right now, and none of them can be ‘aliens.’”

“Is one of them ‘you got a sugar daddy’?” I asked, rubbing my temples.

“That’s number one, yes,” she said. “Number two is ‘drug lord looking for his money,’ and number three is ‘FBI witness relocation gone wrong.’ We also have a side bet on ‘secret husband.’”

“Can confirm it’s not FBI or drugs,” I said. “The rest is TBD.”

She was quiet for a beat.

“You okay?” she asked more softly.

I exhaled.

“I don’t know yet,” I admitted.

She listened as I told her everything—the cars, the old man, the photograph, Ethan, the word dead.

“Oh, Grace,” she said when I finished. “I’m so sorry.”

“I don’t know what I expected,” I said, pacing the kitchen while Noah took his shower. “I mean, what did I think he’d been doing for ten years? Backpacking in Europe? Working at some gas station in Tulsa? That maybe one day he’d just show back up with a sheepish grin and a ‘my bad’? Hearing he’s dead and has been this whole time makes me feel like an idiot and a widow at the same time.”

“You’re neither,” she said. “You’re a woman who loved a man who didn’t stick around and then died before he could fix it. That’s not on you.”

“And the old man?” I asked. “What do I even do with that?”

“What does Noah want?” she asked.

I glanced down the hall.

He’d been quiet all afternoon. After Walter left, he’d peppered me with questions until his mouth outran his brain and he’d crashed on the couch. When he woke up, he’d gone straight to his room with his workbook, muttering something about “Googling DNA tests.”

“I don’t know yet,” I said. “I’m trying not to overload him.”

“Too late,” she said. “You’ll figure it out. Just—don’t let anyone make you feel small in this. Not him. Not Old Man Moneybags. Not this town.”

“I won’t,” I said.

“You always say that,” she replied. “Then you shrink so the rest of us don’t get uncomfortable. Not this time, Grace.”

She hung up.

I stared at the phone.

Not this time.

In the morning, the stares at the school were worse than usual.

“Grace,” Principal Weller said as I walked into the office, “anything you want to tell me about the…fleet of vehicles in front of your house yesterday?”

His tone was light, but his eyes were sharp.

“Halloween decorations,” I said, dropping my bag. “Going for a Mafia theme this year.”

He cracked a smile.

“Well, if you ever decide to add a third job as a mob boss, we could use the funding for new computers,” he said.

He walked away whistling.

The whispers followed.

By the time the last bell rang, half the staff knew the phrase “rich grandfather,” and the other half had invented their own soap opera plots.

I drove home with my stomach in a knot.

Noah climbed in the passenger seat, backpack slung over one shoulder.

“How many people asked you about it?” I said.

“Three teachers, eight kids, and the nurse,” he said, buckling his seatbelt. “That old lady from church said she knew it, you were ‘one of those girls’ who’d luck into money eventually.”

My grip on the steering wheel tightened.

“What’d you say?” I asked.

“I said if ‘those girls’ meant ‘the ones who work three jobs and never miss a parent-teacher conference,’ then yeah, you’re one of those girls,” he said.

My throat tightened.

“That’s my boy,” I managed.

At 3:02, Walter’s car pulled up.

Just one this time.

A glossy black sedan that still looked like it cost more than our block.

Walter stepped out alone.

He wore jeans and a button-down today, no tie, his hair a little messier, like he’d had a fight with the wind and lost.

He carried a bakery box.

“I brought bribes,” he said. “Peach cobbler. I heard from…someone that you like it.”

“Who’d you hear that from?” I asked.

He shrugged. “A waitress at Deacon’s. She was happy to talk once I tipped her.”

“Sylvia,” I muttered. “Traitor.”

Noah hovered behind me, half in, half out of the doorway.

“You can come out,” Walter said gently. “I don’t bite.”

“Stranger danger,” Noah said.

Walter blinked.

“Stranger…?”

“Rule number one,” Noah said. “Strangers don’t get to tell you they’re your grandpa and then just take you somewhere.”

Walter looked at me, almost impressed.

“He’s smart,” he said.

“Annoyingly so,” I replied. “Come on in. But shoes off. I don’t care how rich you are, no one tracks dirt on my floors.”

To his credit, Walter toed off his expensive loafers without argument.

He set the cobbler on the counter, looked around our little kitchen like it was a museum.

There was no judgment in his eyes.

Only…curiosity.

“This is where you’ve been raising him,” he said.

“This is where we’ve been living,” I corrected. “I raise him everywhere. In the car. At the grocery store. In the school parking lot. Geography is flexible when you’re poor.”

He huffed a little laugh.

Noah slid into a chair at the table, eyes never leaving Walter’s face.

“So,” Noah said. “You’re really my grandpa.”

Walter swallowed.

“If a DNA test says so, yes,” he said. “And if your mother agrees.”

Noah’s gaze swung to me.

“DNA test?” he echoed.

I shot Walter a look.

He held up his hands.

“I’m not assuming,” he said quickly. “I believe he’s my grandson. But I also know memory plays tricks. Photos can be faked. I don’t want to show up in your lives and say ‘this is truth’ without giving you a way to verify it. I can arrange it. Quietly. Privately. Or not at all. It’s up to you.”

Noah leaned forward, eyes shining.

“Can we do it?” he asked me. “A DNA test? Like on those ancestry commercials?”

“Buddy, this isn’t about finding out if you’re fourteen percent Viking,” I said.

He shrugged. “Yeah, but…don’t you want to know? For sure?”

I did.

And I didn’t.

“Yes,” I admitted. “I do.”

“Then let’s do it,” he said. “Unless you’re…scared it’s not true.”

There was no accusation in his tone.

Just a kid calling it like he saw it.

I sat down heavily.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll do it. But only if I’m in the room. No weird backroom swabbing.”

Walter nodded.

“Of course,” he said. “I’ll have my assistant set it up at a clinic in the city. We’ll go together.”

Noah grinned.

“Cool,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to spit in a tube for science.”

Walter laughed, his shoulders loosening a little.

“Now,” he said, “may I ask you some questions, Noah? Only if you feel comfortable.”

Noah glanced at me.

I nodded.

“Okay,” he said.

Walter’s questions weren’t what I expected.

No talk of grades or sports or whether he wanted to go to some fancy private school.

He asked about Noah’s favorite subject (“science, because experiments are just magic you can explain”), his favorite meal (“Mom’s chili, but don’t tell the cafeteria”), his favorite superhero (“Spider-Man, obviously”).

“Why obviously?” Walter asked.

“Because he’s just some kid and then he lucks into powers,” Noah said matter-of-factly. “He’s not rich like Batman or an alien like Superman. He’s just…regular. Like me. Like Mom.”

Walter’s gaze flicked to me.

Something softened in his eyes.

“Spider-Man is my favorite too,” he said quietly.

Noah’s face lit up.

“Really?” he said.

“Really,” Walter said. “Especially the part where he learns that having power doesn’t mean much if you don’t use it to help people.”

Ouch, I thought.

Subtle.

After an hour, Noah had extracted from Walter the names of every state he’d been to, the number of times he’d been on a plane (“more than I can count”), and whether he’d ever met anyone famous.

“George Strait once,” Walter said. “At a charity dinner. Nice guy. Shorter in person.”

Noah’s jaw dropped.

“Mom loves George Strait!” he exclaimed. “She sings ‘Carrying Your Love With Me’ off-key in the kitchen.”

Walter smiled.

“Does she now?” he said.

“Traitor,” I muttered again.

By the time Walter left, the air between us had shifted.

It wasn’t trust.

Not yet.

But the edges were less sharp.

When the DNA results came back two weeks later, they confirmed what our hearts had noticed the second their eyes met.

Noah was his grandson.

Eighty-nine point something percent match on the paternal side.

Noah memorized the number, reciting it like a secret code.

“It’s science,” he told me. “You can’t argue with science.”

Turns out, you can argue about what to do with it.

And that argument got very, very serious.

It started with an envelope.

Thick. Cream-colored. Our address written in precise black ink.

I found it wedged in the screen door after work one day.

Inside was a letter on Hale Enterprises letterhead.

Dear Ms. Miller,

It was a pleasure meeting you and Noah these last weeks. I cannot express how grateful I am that you have allowed me into his life.

I would like to formally invite you both to Dallas for a visit over Thanksgiving break, at my home. We will, of course, cover all travel expenses. I would also like to discuss setting up a trust in Noah’s name to provide for his education and future needs.

I understand this is a lot. Please know that none of this is meant to take anything away from the life you’ve built. My hope is to add to it.

Warmly,

Walter James Hale

Below that, in smaller type, was a note:

P.S. Noah – I’ve got tickets to a Mavericks game with your name on them if your mom agrees.

I stared at the letter.

I thought of the kids in Noah’s class who’d never seen a real NBA game, who worshipped from cheap seats in front of TVs.

I picture Noah in an arena, lights blazing, chest about to burst with excitement.

Then I pictured him a thousand miles away, in a mansion I’d never seen, with people I didn’t know.

“You’re frowning, which usually means bills or boys,” Noah said, dropping his backpack on the counter. “Which is it?”

“Both, in a way,” I said, handing him the letter.

He scanned it quickly.

His eyes grew big.

“A Mavericks game,” he breathed. “Mom. The Mavs.”

“I know,” I said.

“And a plane,” he said. “I’ve never even been to the airport. Do they really have moving sidewalks?”

“That’s what they say.”

He looked up, hope and wariness mixed in his eyes.

“Can we go?” he asked. “Please?”

I opened my mouth to say no.

To say it was too much, too fast.

To say I didn’t want my child dazzled by a life I couldn’t give him, only to have it ripped away if some rich old man changed his mind.

Instead, I heard myself say, “We can…think about it.”

He exhaled, grinning.

“That’s not a no,” he said. “I’ll take ‘think about it.’”

We did.

We talked.

We argued.

Sometimes quietly, sometimes not.

“You’re not listening to me,” I said one night, after he’d brought it up for the tenth time in a week. “This isn’t just a vacation. This is a whole other family. A whole other world. Once you step into it, you can’t un-know it exists. That complicates things.”

“So I’m supposed to pretend I don’t have a grandpa?” he shot back. “That I don’t have cousins and a big house and—and maybe college money?”

“You do have college money,” I said. “In a coffee can in the pantry.”

He rolled his eyes.

“Mom,” he said. “I’m not stupid. I know things are tight. I hear you on the phone with the power company. I see the bills on the table. You work all the time. You’re tired. You think I don’t notice?”

“I don’t want you to have to notice,” I said, my voice cracking.

“Well, I do,” he said. “And now there’s this guy who says he can help. Who wants to help. And you’re…what? Saying no out of pride?”

“It’s not pride,” I snapped. “It’s caution. Rich people don’t do things out of the goodness of their hearts, Noah. They always want something. They always expect something. They treat everything like a transaction.”

He looked at me with a kind of impatience I’d never seen on his face before.

“You’re doing that thing,” he said.

“What thing,” I demanded.

“The thing where you assume you know, because that’s how it’s always been for you,” he said. “But I’m not you. I get to make my own mistakes.”

That stung.

“I’m not trying to control you,” I said. “I’m trying to protect you.”

“Sometimes those are the same thing,” he said softly.

Silence fell between us.

He broke it first.

“I love you,” he said. “I’m always going to love you. Nothing about this changes that. But if you make me choose between you and him, or you and Dallas, or you and college…I’m going to be mad at you. For a long time.”

I felt like someone had punched me in the throat.

“You think I’m making you choose?” I whispered.

“You’re making yourself the only safe choice,” he said. “That’s not the same.”

He turned and walked to his room, shoulders stiff.

The argument didn’t end that night.

It simmered.

It boiled.

It spilled over in the most public way possible two weeks later, when the town’s worst gossip decided to get involved.

We were at Deacon’s, because old habits die hard and sometimes you need fries more than you need privacy.

Noah sat across from me in a booth, stabbing at his burger.

“Do you even know what kind of food they have in Dallas?” he asked. “Probably barbecue every day. And tacos.”

“We have tacos here,” I said. “Taco Bell counts.”

He gave me a look that said he didn’t think that was funny.

The bell over the door jingled.

The noise in the diner dipped.

I didn’t have to turn to know someone interesting had walked in. You can feel it in your bones when group attention shifts like that.

“Grace!”

The voice was syrupy sweet and sharp as a knife.

I clenched my jaw before I turned.

There, in all her oversized-sunglasses, perfect-hair glory, stood Vanessa Cline. PTA president, church choir soloist, woman who’d once told her daughter within earshot of me, “Some women just don’t value themselves.”

She made her way to our booth like she owned the place.

“I heard you’ve been keeping secrets,” she said, sliding into the seat next to Noah uninvited. “Mind if I join you?”

“Yes,” I said.

She ignored me.

“So,” she said to Noah, “I hear you’ve got yourself a rich granddaddy now.”

Noah stiffened.

“How’d you hear that?” he asked.

She waved a hand.

“Small town, sweetheart,” she said. “People talk. Plus, it’s hard to miss three shiny black cars on your street. Bit of a step up from your mom’s little Honda, huh?”

Noah’s cheeks flushed.

“So?” he said cautiously.

“So,” she drawled, leaning in, “are you going to forget about us little people when you move to your mansion? Or are you still going to come back and grace us with your presence?”

“We’re not moving,” I cut in.

She glanced at me, eyebrows arched.

“Aren’t you?” she said. “Because if some billionaire came knocking on my door and said ‘let me take you away from all this,’ “ – she gestured around at the cracked vinyl and cheap coffee – “I’d be on a plane so fast my flip-flops would catch fire.”

“That’s because you’d leave your kids behind,” I said.

Her smile tightened.

“I never got myself in that situation,” she said. “Smart girls don’t.”

Heat flared in my chest.

Noah shifted uncomfortably.

“Leave us alone, Mrs. Cline,” he muttered.

She patted his hand.

“I’m just concerned, is all,” she said. “About what this will do to our community. Folks already feel like you think you’re better than them, Grace. Always so…defensive.”

“I wonder why,” I said. “Could it be because people like you have been calling me a whore to my face since I was twenty-two?”

A hush fell over the nearby tables.

Vanessa’s eyes flashed.

“I never said that word,” she said primly. “I said ‘reckless.’”

“You said ‘whore’,” I shot back. “At the laundromat. In front of my son. He was six. He asked me what it meant.”

Several heads turned our way.

Sylvia appeared at the counter, arms crossed, watching.

“Well,” Vanessa said, “if the shoe fits—”

“Don’t,” Noah said suddenly, loud enough that heads snapped in his direction. “Don’t talk about my mom like that.”

Vanessa blinked.

“Oh, honey,” she said. “I’m just being honest—”

“You’re being mean,” he said. “My mom worked two jobs and never missed a game. She goes to all the parent nights even when you and your friends pretend not to see her. She does more for this town than most of the people who talk about her. If she was a whore, people would pay her. They don’t. They just take.”

Laughter broke out at a back table.

Even Sylvia snorted.

Vanessa’s face went scarlet.

“How dare you—” she began.

“How dare you,” I cut in. “Talk about my kid. Talk about my life. You don’t know anything about what I’ve been through. You’ve had the same husband since you were nineteen. You had parents who paid for your first house. You’ve never been hungry. You’ve never had to decide between rent and medicine. You think if you sit in the front pew and put a casserole in every grieving family’s oven, that makes you better than me.”

“I know it does,” she said. “Because I have standards.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Double ones.”

She opened her mouth.

I held up a hand.

“Don’t,” I said. “I’m done. You don’t get to say another word about me or my son. Not now, not at church, not in the school parking lot. If I hear you so much as breathe my name in a grocery aisle, I will turn this town upside down with what I know about you.”

Her eyes widened.

“You don’t know anything,” she said weakly.

“Try me,” I said.

It was a bluff.

Mostly.

I didn’t have dirt on Vanessa.

But I had ten years of rage.

It must’ve showed.

She sniffed, stood.

“This is exactly what I mean,” she said. “You’re combative. Rude. You think just because some rich man fell out of the sky and decided to claim your mistake, that changes who you are.”

“No,” I said. “It changes who you are. Because when he comes back to town, and he will, he’ll see who stood by me and who kicked dirt in my face. And when he wants to invest in schools or parks or the church…” I leaned in. “I will tell him exactly whose team you were on.”

She faltered.

The thing about people like Vanessa?

They didn’t fear God as much as they feared losing their place at the fundraising table.

“Enjoy your fries,” she said stiffly, and walked out.

The diner buzzed with whispers.

Sylvia made her way to our booth, two milkshakes in her hands.

“On the house,” she said, sliding them toward us. “For the best show I’ve seen in ten years.”

I managed a shaky smile.

My hands trembled.

Noah looked at me like I’d grown a second head.

“Mom,” he said. “You just…stood up to her.”

“I should’ve done it years ago,” I said.

He nodded slowly.

“Yeah,” he said. “You should have.”

There was no accusation in his voice this time.

Just…respect.

Maybe a little awe.

The argument about Dallas didn’t stop.

But that day, something shifted.

He stopped seeing me only as the woman standing between him and opportunity.

He started seeing me as someone fighting for him, not against him.

Walter called that night.

“I heard there was a…scene,” he said drily. “My assistant’s cousin’s wife works at Deacon’s.”

“Of course she does,” I said. “Is your money in the wallpaper too?”

He chuckled.

“I wish I’d seen it,” he said. “Catherine would’ve loved it. She’s been praying somebody would take that woman down a peg for years.”

I blinked.

“You know Vanessa?” I asked.

“We’ve been quietly donating to your school district for a long time,” he said. “My wife keeps track of the…characters.”

Of course.

Of course the Hales’ fingerprints were on Maple Ridge money.

The irony made my head spin.

“Have you thought any more about Thanksgiving?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“And?”

“And we’ll come,” I said. “For a visit. Not a relocation. A visit. We fly in Wednesday. We fly back Sunday. We stay in a hotel, not your house.”

“Ms. Miller,” he began.

“That’s the deal,” I said. “Take it or leave it.”

He was silent for a moment.

“Okay,” he said finally. “Deal.”

Noah whooped in the background when I told him.

His joy smoothed some of the jagged edges inside me.

Thanksgiving loomed like a storm on the horizon.

Before we could get to the turkey, though, another bomb dropped.

Walter’s lawyers filed for partial custody.

It came in another envelope.

Thicker.

Heavier.

This time delivered by a man in a suit who said my name like he’d been practicing.

“Ms. Miller?” he asked. “You’ve been served.”

I watched him walk back to his car, numb.

Inside: legal language. Best interest of the child. Paternal grandfather. Joint conservatorship. Words circled in red, highlighted.

I called Walter, fury boiling.

“What the hell is this?” I demanded without hello.

A pause.

“Grace,” he said. “I told them to hold off—”

“So you knew,” I said. “You knew they were doing this.”

“I didn’t authorize it,” he said quickly. “I mentioned to my attorney that I wanted to be legally recognized as Noah’s family, so there would be no issues with medical decisions or travel. He…took it too far.”

“Too far?” I spat. “He filed to take my son.”

“That is not what this says,” he insisted. “Read it again. We’re asking the court to recognize me as a joint conservator. It doesn’t strip you of anything. It just—”

“Just gives you rights you can use against me,” I said. “If you decide I’m not doing a good enough job. If you decide Maple Ridge is dragging him down. If you decide the school isn’t fancy enough or my car isn’t safe enough or my house isn’t big enough—”

“Grace,” he cut in, “my son died without ever letting me help him. I am not going to stand by and let my grandson grow up without legal protection.”

“He has legal protection,” I said. “Mine.”

“And what if something happens to you?” he asked, his voice rising. “What then? He ends up in foster care? Bounced around? You think I’m going to let that happen when I have the means to give him stability?”

“You don’t get to use my death as a hypothetical club,” I snapped.

“I’m trying to make sure it stays hypothetical,” he said. “I’m old, Grace. I don’t have another ten years to waste. I need to know that if I die, Noah is taken care of. That I have the legal right to do that.”

“And you couldn’t just ask?” I said. “You had to send lawyers?”

“I…was trying to do it right,” he said weakly.

“You did it wrong,” I said. “So very wrong.”

“We can fight it,” he said. “We can modify it. Withdraw it. I’ll talk to him—”

“Don’t bother,” I said. “I’ll see you in court.”

I hung up.

My hands were shaking.

The protective rage in my chest felt like a wild animal.

I called Ruth, the public defender who’d helped Sylvia with her divorce.

“You’re going to need more than my discounted rate for this,” she said after reading the paperwork. “But I’ll find you someone. Someone good.”

“You think he can win?” I asked.

She sighed.

“He’s rich,” she said. “He’s respected. He’s got a story about wanting to be involved in his grandson’s life. Judges eat that up. But you’re his mother. Unless you’re neglectful or abusive, he’s not going to take Noah away from you. Joint conservatorship is not the same as custody. It’s messy. But it’s not hopeless.”

“Messy,” I repeated. “My specialty.”

Noah overheard the tail end of the call.

He stood in the doorway.

“They’re going to make us go to court?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, sitting heavily. “To decide what your life looks like.”

He chewed his lip.

“Does this mean…” he hesitated. “Does it mean I have to choose? Like, pick a side?”

The desperation in his voice sliced me open.

“No,” I said immediately. “You don’t have to choose between us. I won’t let them make you do that.”

He nodded slowly.

“I want both,” he said. “You and him. This town and Dallas. Is that greedy?”

“It’s human,” I said. “And if anybody tries to tell you it’s greedy, I’ll punch them. Even if it’s a judge.”

He cracked a small smile.

“You’d probably go to jail,” he said.

“Worth it,” I said.

The day of the hearing, Maple Ridge turned out like the circus was in town.

Everybody suddenly had errands at the county courthouse.

Sylvia was there, of course, sitting behind me, a hand on my shoulder.

Vanessa hovered near the back, lips pursed, eyes bright.

Walter sat at the other table, flanked by two attorneys in crisp suits.

He looked smaller than I’d ever seen him.

Older.

His hands trembled slightly as he smoothed his tie.

Our eyes met.

For a moment, his expression was naked.

Regret.

Fear.

Love.

Then he looked away.

The judge, a woman in her fifties with sharp eyes and a soft mouth, called us to order.

She’d grown up in the next county over.

She knew the rhythm of small towns, the way gossip could warp truth.

As the attorneys made their arguments, I felt like I was watching someone else’s life.

“Ms. Miller has worked tirelessly to provide for her son,” my lawyer, a woman named Denise, said. “She has no criminal record. No history of substance abuse. Her son is thriving in school. The only question before the court is whether Mr. Hale’s involvement—legal and otherwise—is in the child’s best interest.”

Walter’s attorney talked about legacy, about family, about opportunity.

He did not say the word “whore.”

He didn’t have to.

Vanessa’s presence whispered it loudly enough.

At one point, Walter stood to speak.

“Your honor,” he said, voice rough, “I am not trying to take Noah away from his mother. I lost my son. It nearly ruined me. If I tried to repeat that mistake—to cut a boy off from his parent—I’d deserve whatever hell you and God could cook up for me. I just want the law to recognize what science already did. That he is my blood. That I have a responsibility to him. That I am here. That I’m not going anywhere.”

He glanced at me.

“And that I will do that on his mother’s terms,” he added. “Because she’s the one who’s been here. When he had nightmares. When he was sick. When the kids at school repeated their parents’ gossip. She didn’t have to let me in. She did anyway. I’m the one asking for more. If you grant it, I promise I will earn it.”

My throat burned.

When it was my turn, my legs shook as I walked up.

The judge watched me like she’d seen a thousand women like me and still cared about what each one said.

“Ms. Miller,” she said. “What do you want?”

I looked at Noah.

He sat on the bench, hands clasped, eyes huge.

“I want my son to be safe,” I said. “I want him to know where he comes from, but not be swallowed by it. I want him to have opportunities, but not at the cost of his soul. I want him to be able to go to a Mavericks game with his grandpa and still come home to me. I want…both.”

Emotion thickened my voice.

“I’ve done everything I can for ten years with what I had,” I went on. “Sometimes that wasn’t much. We ate ramen. We wore thrift store clothes. We didn’t go on vacations. But he was loved. He is loved. That’s not nothing. I’m proud of what we’ve built in our little house with the saggy porch. I’m not ashamed.”

I turned to look at the courtroom.

“At what I am ashamed,” I said, letting my gaze land on Vanessa, “is how this town treated us. How they treated me for daring to be a woman who made a mistake and admitted it. How they treated him for being born. They called him an orphan when he had a mother. They whispered ‘whore’ loud enough for a six-year-old to hear. They judged us for being poor, then resent us when a rich man shows up and cares. That shame does not belong to me. It belongs to them.”

A murmur rose.

The judge banged her gavel.

“Order,” she said.

I turned back to her.

“I don’t want to keep Noah from his grandfather,” I said. “I want to protect him from this town. From people who only like success when it’s theirs. I’m asking you to give me that chance. To let me remain the primary decision-maker in his life, with input from Mr. Hale, not the other way around. To trust that a woman can make good decisions for her child even if she doesn’t have a last name that’s on a building.”

When I finished, my knees felt like jelly.

I managed to get back to my seat without collapsing.

The judge called a brief recess.

People buzzed.

In the hallway, Walter approached me.

“Grace,” he said.

I held up a hand.

“Don’t,” I said. “If you say ‘I’m sorry,’ I might actually hit you, and I don’t think that’ll help your case.”

He actually smiled.

“I wasn’t going to apologize,” he said. “Not because I don’t need to. Because I realized something. I’ve been fighting for rights I assumed I deserved because of blood and money. But you’ve been doing the work for ten years without either. Rights are just paper. Work is real.”

He took a breath.

“I told my attorney to withdraw the petition,” he said.

I blinked.

“What?”

“I don’t need the court to tell me I’m his grandpa,” he said. “It doesn’t change how I feel. It doesn’t change DNA. It only changes your life in ways you didn’t ask for. I can set up a trust with or without a piece of paper. I can love him with or without legal jargon.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, stunned.

He nodded.

“I watched him look between us during your speech,” he said. “I saw the panic on his face. I swore I’d never be the reason a child of mine had to choose between love and stability. I don’t want to win this in a courtroom. I want to win it in daily life.”

Before I could answer, Noah barreled into the hall.

“Mom,” he said, breathless. “Is it over? Did we lose?”

“We didn’t lose,” Walter said. “We…called a truce.”

The judge confirmed it a few minutes later.

“Mr. Hale has withdrawn his petition,” she said. “The court recognizes Noah’s relationship with both his mother and grandfather as beneficial. Any formal agreements regarding travel, visitation, and trust funds can be handled privately. This hearing is concluded.”

Gavel.

Done.

The town filed out, buzzing like flies.

Vanessa brushed past me.

For the first time in ten years, she looked…uncertain.

“Grace,” she began.

I walked right by her.

Noah grabbed my hand on one side.

Walter, hesitating only a moment, reached for it on the other.

I let him.

We walked down the courthouse steps together.

Three generations of a family that had taken the long way around to find each other.

Outside, a few reporters from the city hovered with cameras.

“Ms. Miller!” one called. “Any comment?”

I thought of all the years my story had been told without me.

Not this time.

“Yeah,” I said. “Tell them the whore won.”

The reporter’s eyes went wide.

Noah snorted.

Walter barked out a laugh.

Later, when the article ran, that line became the headline.

It was dramatic.

A little crude.

Very American.

People in Maple Ridge tutted.

People online cheered.

It didn’t fix everything.

Gossip didn’t evaporate.

Bills didn’t disappear.

Walter didn’t magically become the perfect grandfather.

But it did something.

It told the story my way.

Two years later, on a bright May afternoon, I sat in the bleachers of the Maple Ridge High football field, the sun on my face, a program in my lap.

At the 50-yard line, rows of folding chairs held the graduating class.

Somewhere in the middle—cap crooked, gown too long, sneakers peeking out from underneath—sat my son.

He was taller now.

Six-one, just like I’d predicted. Maybe he’d get the extra inch.

Beside me, Walter adjusted his sunglasses.

“This thing always take this long?” he grumbled.

“Calm down, Spider-Man,” I said. “You survived board meetings. You can survive a high school commencement.”

He grunted.

On my other side, Sylvia waved a homemade sign that said YOU DID IT, NOAH! with a badly drawn spider.

“I should’ve gone into graphic design,” she said.

“Stick to waitressing,” I replied.

We watched as the valedictorian droned on about journeys and horizons and the future.

Noah had been accepted to a state school two hours away, on a partial scholarship. The rest would be covered by a combination of financial aid, a single-mom-stubbornness fund, and a trust account Walter had set up in both our names, with my signature required for withdrawals.

“Checks and balances,” he’d said. “Like the government, except ours might actually work.”

Noah had spent Thanksgiving in Dallas that first year.

Christmas at home.

Spring break somewhere in the middle, at a halfway point in Oklahoma where Walter rented a cabin and we all nearly killed each other trying to assemble an IKEA bunk bed.

It wasn’t perfect.

We argued.

We made up.

We learned.

The town adjusted too.

Some people never changed.

They still whispered.

But other people—people I hadn’t expected—stepped up.

Principal Weller started calling out bullying when he saw it.

The pastor preached a sermon about grace that made Vanessa squirm.

The school board accepted a Hale Foundation grant to rebuild the playground.

They didn’t put Walter’s name on it.

At his request.

“I don’t need my name on a swing set,” he said. “I’ll take it on a certificate that says your kid is the first in your family to go to college.”

On the field, Noah’s row stood.

My chest tightened.

He walked across the stage.

They called his name: “Noah James Miller-Hale.”

He’d added the hyphen without asking.

“I want both,” he’d said. “You and him. Always both.”

The principal handed him his diploma.

He shook the superintendent’s hand.

He turned, searching the stands.

Our eyes met.

In that moment, I saw a thousand versions of him.

The baby whose father never came home.

The six-year-old who asked what “whore” meant.

The twelve-year-old who Googled DNA tests.

The fourteen-year-old who stood up for me in a diner.

The eighteen-year-old walking into a future none of us could’ve imagined the day those black cars rolled onto our street.

He grinned.

He lifted his hand.

For a second, just to mess with him, I pretended not to see.

Then I shot both arms in the air and screamed his name like a lunatic.

Walter winced at the volume.

Sylvia whooped.

People turned.

Some smiled.

Some rolled their eyes.

I didn’t care.

After the ceremony, in the chaos of hugs and photos and teenagers throwing caps, Vanessa approached me.

Her hair was perfect.

Her smile brittle.

“Grace,” she said.

“Vanessa,” I replied.

She looked at Noah laughing with his friends, Walter snapping a picture on his phone like any other grandpa.

“You did good,” she said quietly.

I studied her face, looking for sarcasm.

There was none.

“Thanks,” I said. “Took a village. And a very stubborn old man with too much money.”

She nodded.

“Maybe I judged you too harshly,” she said. “Back then.”

“You did,” I said.

She flinched.

“I’m…sorry,” she said, the word sounding foreign on her tongue.

I let it hang there.

For years, I’d dreamed of this moment.

Of a groveling apology.

Of vindication.

Now that it was here, it felt…small.

“I appreciate that,” I said. “I hope you teach your kids to apologize faster than you did.”

A flush crept up her neck.

“I will,” she said. “Congratulations, Grace. Really.”

She walked away.

I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I’d been holding.

“What’d she want?” Sylvia demanded.

“To feel better about herself,” I said. “Too bad.”

Noah walked over.

His cap hung from his hand.

“Mom,” he said, “Grandpa wants a picture of the three of us.”

He rolled his eyes affectionately.

“He’s got, like, a thousand on his phone already.”

“They’re all blurry,” Walter grumbled, joining us. “People keep moving. We’ll get one nice one if it kills me.”

We leaned in.

The sun was too bright.

I squinted.

Noah slung an arm around each of our shoulders.

Walter held the phone, his hands steadier than I’d seen them in years.

“Say ‘whore won,’” Sylvia called from behind the lens.

“Don’t you dare,” I warned.

“Say ‘we did it,’” Noah said.

“We did it,” I said.

Flash.

Click.

Capture.

Later that night, after the folding chairs were stacked and the field was empty, I sat on my sagging porch step, the cicadas singing in the dark.

My phone buzzed.

A text from Walter.

The photo.

Me, mid-laugh, head thrown back.

Noah, eyes bright, cheeks flushed.

Walter, smiling in a way that made him look ten years younger.

Below it, a message:

Not bad for a whore and an old fool, huh?

I snorted.

Typed back:

Not bad for a kid they called an orphan, either.

He replied with a spider emoji.

I rolled my eyes.

Inside, Noah packed a duffel for college orientation.

On the coffee table sat a stack of acceptance letters, scholarship offers, and a Hale Foundation check made out to both of us.

Ten years ago, the town whispered that I’d ruined my life.

That I’d ruined his.

They called me a whore.

They called him an orphan.

They were wrong about both.

I’d made mistakes.

I’d fallen for the wrong man.

I’d raised my voice too late.

I’d shrunk for too long.

But I’d also done something else.

I’d stood in a cracked yard, faced down money and gossip and fear, and said, This is my son. This is my story. You don’t get to write it without me.

I didn’t know what the next ten years would bring.

Maybe more fights.

More tears.

More courtrooms.

More arenas.

More graduations.

But I knew this:

When the next three black cars drove onto my street, or the next old man with a confession knocked on my door, I wouldn’t be that scared twenty-two-year-old anymore.

I’d be the woman who watched her grandson’s eyes light up when his grandfather showed him the view from an airplane.

The woman whose son knew he came from both cracked porches and glass skyscrapers.

The woman who’d finally realized she didn’t have to pick between shame and survival.

She could have both survival and pride.

And maybe—just maybe—love, too.

For herself.

For her son.

For the broken town that had tried to break her.

For the ghost of a man she’d loved once, in the back of a truck by the lake, who’d left her with the best and hardest thing in her life.

That was my story.

And no one whispered it behind my back anymore.

They had to say it to my face.

THE END

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load