Pregnant at Sixteen, Kicked Out in Shame — Twenty Years Later, My Parents Begged to Meet a Grandson Who Didn’t Deserve Them

When the doorbell rang that Saturday, I was standing at the stove stirring a pot of boxed mac and cheese, trying to convince my ten-year-old that the orange powder counted as “real cheese.”

“Mom,” Tyler called from the couch, eyes glued to his video game, “the controller’s lagging again, that’s why I keep dying.”

“It’s never your fault, is it?” I said, smiling as I tapped the lid of the pot. “Dinner in five.”

The doorbell rang again. Harder. Someone leaning on it like they were owed something.

I frowned. I wasn’t expecting anyone. All my friends knew to text first. The only people who just showed up were Girl Scouts and the neighbor who liked to complain about recycling bins.

“Pause your game,” I told Tyler. “Someone’s at the door.”

He groaned theatrically but hit pause and followed me into the small entryway, socks sliding on the hardwood. I wiped my hands on a dish towel and pulled the door open with the kind of casual, distracted politeness you give strangers.

It wasn’t a stranger.

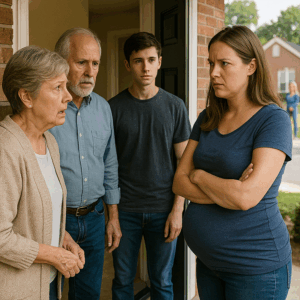

It was my parents.

For a second, my brain genuinely couldn’t make the pieces fit. Like someone had cut them out of an old photograph and pasted them onto my front porch.

My mom, Peggy, in her church-nice cardigan and that same stiff perm she’d had since the late ‘90s, gone more silver than blonde. My dad, Richard, in a pressed button-down tucked into jeans, one hand on the porch rail like he needed it to stay upright.

Behind them, the cul-de-sac of my Indianapolis suburb glowed normal and harmless, kids’ bikes on lawns, a golden retriever two doors down barking at a squirrel.

Inside me, seventeen-year-old me was suddenly wide awake and screaming.

“Hi, Jenna,” my mother said.

She said my name like it tasted strange.

“Hey, kiddo,” my father added, voice rough.

“Mom?” Tyler whispered behind me, his hand brushing my elbow.

They both looked at him.

And that was when I understood why they were here.

My stomach dropped.

My mother’s eyes filled, her hand flying to her chest.

“Oh my Lord,” she breathed. “Is that… is that him?”

My dad swallowed. “He looks just like you,” he said. “We… we were hoping that—”

“Tyler,” I cut in, my voice sharper than I meant. “Go finish your game, okay? Mac and cheese is almost done.”

He squinted up at my parents, curiosity all over his face. “Who are they?” he asked, not moving.

“They’re nobody you need to worry about,” I said, eyes still on my parents. “Go on.”

He must’ve heard something in my tone, because he obeyed without argument, backing down the hall, still staring.

My mother’s lips trembled. “Jenna, honey—”

“Don’t call me honey,” I said.

She flinched.

The last time my parents had stood in front of me like this, I’d had a backpack on, morning-sick and terrified, the front door to their house slamming behind me.

That had been two decades and a lifetime ago.

“Can we come in?” my father asked, glancing past me into my little rental house like it was a museum exhibit.

“No,” I said. “You can’t.”

He drew back slightly, like he’d expected that but hoped he was wrong.

“Jenna,” my mom tried again, voice wobbling. “We drove all this way. We just want to talk. To see our grandson.”

“Our grandson,” my dad echoed. “Please.”

The word burned.

For twenty years, I’d built a life around the hole they’d left. For twenty years, I’d told myself they were as gone as if they’d died.

Now they were on my doorstep, suddenly full of “please.”

I could’ve slammed the door.

I thought about it.

Instead, I pulled it a few inches closer, just enough to make it clear they weren’t welcome, but not enough to make my neighbors call the HOA.

“You have two minutes,” I said. “On the porch. Then you leave. Got it?”

My father nodded quickly. My mother sniffled and dug a tissue out of her purse, like she’d rehearsed this scene in the car.

“We heard you moved back,” she said, dabbing her eyes. “Tammy’s daughter saw you at the Kroger in Avon and told her mama, and, well, word gets around. We— We’ve been praying for you.”

I huffed a humorless laugh. “Have you.”

“We have,” Dad said. “Every night. We’ve asked for a chance to make things right.”

“I didn’t realize you and God were still on speaking terms,” I said. “Figured He might’ve stopped answering your calls after you threw your pregnant daughter out on the street.”

My mother flinched like I’d slapped her.

“We made mistakes,” she said. “We were scared. We didn’t know how to handle—”

“You knew how to handle it well enough to drag me in front of Pastor Dan and the whole church council,” I said. “You knew how to tell every woman in the congregation to ‘pray’ for me while they whispered about what a little tramp your daughter turned out to be. You knew how to take my key and tell me not to come back until I’d repented.”

The words came out sharper than I’d planned. They’d been sitting under my tongue for twenty years.

My father’s jaw tightened. “We thought we were doing the right thing,” he said.

“Well, congrats,” I said. “You did it so right I still have nightmares about your face when I told you I was pregnant.”

Dad’s nostrils flared. “You were sixteen,” he said. “We raised you better than that. You were supposed to be an example. Head of the youth group, straight-A student, first chair clarinet. And then suddenly you were… pregnant.”

“Yep,” I said. “That’s how it works when a sperm meets an egg. Sometimes even in Bible Belt suburbs. You should’ve gotten the abstinence-only curriculum a better PR team.”

“Don’t be crude,” my mother whispered, glancing nervously at my neighbors’ houses.

“Don’t be a hypocrite,” I shot back.

The air on the porch buzzed with summer heat and old anger.

My father exhaled slowly. “We didn’t come here to fight,” he said. “We came because… we’re getting older, Jenna. Your mom’s blood pressure’s not great. I’ve had a scare or two. We realized… time is short.”

“And?” I asked.

“And we want to see him,” Mom said, gesturing vaguely toward the hallway where Tyler had disappeared. Her voice cracked. “Your boy. Our grandson. We’ve missed so much already, we know, but… but we’d like to be part of his life now. If you’ll let us.”

It was almost funny, how quickly the conversation had skipped over twenty ruined years to “we’d like to be part of his life now.”

“His name is Tyler,” I said. “And you don’t get to want anything where he’s concerned.”

“We’re his grandparents,” my mother said, a hint of steel under the wobble.

“No,” I said. “You’re not.”

My father frowned. “You just said—”

“I said you don’t get to want anything where he’s concerned,” I repeated. “Because he’s not your grandson. He’s mine. Period.”

My dad’s face went red. “Biology says otherwise,” he snapped. “We might’ve made mistakes, but we can’t change the fact that he’s blood.”

I stared at him.

“Oh, you want to talk about biology?” I asked softly. “Fine. Let’s talk about biology.”

The argument had turned serious, the way a summer storm turns from threatening to real in a snap of thunder.

I could feel the old me, the scared teenage girl who’d vomited on the bathroom floor and then stared at the pink plus sign with shaking hands, watching from somewhere deep inside.

She’d wanted her parents to hold her hand.

They’d told her to pack a bag.

“You asked for this,” I said. “You drove all this way. You said you wanted the truth. The truth about your ‘grandson.’”

My mother nodded, eyes wide and wet.

“Okay then,” I said. “Here it is.”

1. Before the Door Slammed

If you want to understand why it felt like the universe was folding in on itself on my front porch that day, you have to go back to the first door that closed on me.

The front door of 904 Maple Street.

I grew up in a small town off I-70 in Indiana, the kind of place with one high school, three churches, and two stoplights that everyone pretended was “quaint” and not “claustrophobic.”

My parents were fixtures. Dad was a deacon at Hope Baptist. Mom ran the nursery and organized the meal trains whenever someone had a baby, a surgery, or a mildly inconvenient cold.

We were the Harts. Church people. Clean people. My mom ironed my socks when I was little.

From the outside, we looked like a postcard: Dad in his suit, Mom in one of her floral dresses, me and my little brother, Luke, in matching Easter outfits, all smiling into the sun as we stood in front of the brick church.

Inside, it was tighter. Rules wrapped around us like plastic.

No dating until sixteen.

No R-rated movies.

Skirts to the knee.

No “alone time” with boys.

No talking back.

No bringing shame on the family.

I was good at rules.

Until I wasn’t.

His name was Adam Miller. Quarterback, of course. Brown eyes that crinkled when he smiled. The kind of boy mothers warned their daughters about kindly while secretly hoping he’d pick theirs.

Mom liked Adam.

“He’s a church boy,” she said when he first started coming around, hands tucked into his letterman jacket pockets like he didn’t know what to do with them. “Comes from a good family. His mama sings in the choir.”

Dad had been more cautious, but even he eventually relented.

“You can ride with him to youth group,” he’d said. “But no parking. You hear me, Jenna? Straight there, straight back.”

“Yes, sir,” I’d said.

For six months, that’s mostly what we did. Homework, youth group, movies with our friends, the occasional stolen kiss in the parking lot of the Dairy Queen.

The night everything changed, it was raining.

“Just stay and watch a movie,” Adam said, wiping droplets off his forehead as he stood in our foyer. “The roads are slick. I’ll drive you home after.”

Mom was in the kitchen, cooking spaghetti for the youth group leaders meeting she was hosting. She overheard.

“I don’t know…” she said, wiping her hands on a dish towel. “Richard?”

Dad glanced up from the bills at the table. “They can watch a movie,” he said. “Door stays open. Jenna, you’re home by ten.”

“Thanks, Dad,” I said.

I wish he’d said no.

I wish a lot of things.

Adam and I sat on the couch. We put on some superhero movie we’d already seen. The rain drummed against the windows.

Halfway through, Mom called me into the kitchen to help carry trays.

“Front door stays open,” she reminded us. “And no blankets.”

The youth leaders were late. The sauce simmered. Dad disappeared into the garage to look for an extra folding chair.

“You’re doing great,” Mom murmured, patting my cheek. “Pastor Dan says the Lord has big plans for you, Jenna. You’re a leader. A light.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

Back in the living room, Adam rolled his eyes.

“Door stays open,” he mimicked in a high voice.

I shushed him, half laughing, half nervous.

He kissed me. We’d kissed plenty of times before. This one lasted longer. His hand slid under my hair. Mine crept up his chest.

The movie played on.

The front door creaked in the wind and then, slowly, quietly, drifted shut.

I didn’t notice.

I should have.

I know what you’re thinking: This is where it happened. The big moment. The act.

But it wasn’t that simple. It never is.

It wasn’t like we threw ourselves at each other without thought. It was a slow, terrifying, thrilling series of small choices. My hand on his wrist. His breath hot on my neck. The whispered “We should stop.” The quieter “Do you want to?”

We’d both gotten the abstinence talk a dozen times. True Love Waits pledge cards signed in youth group. Purity rings that were really just cheap silver bands that turned your finger green.

All of that felt very far away when he looked at me like I was the only person in the world.

“I love you,” he whispered.

“I love you too,” I said.

I did.

We made a choice.

I made a choice.

Those ten minutes in the dark living room changed everything.

Two weeks later, I threw up in the school bathroom between second and third period.

I told myself it was bad cafeteria pizza.

I told myself a lot of things.

When my period didn’t come, I bought a test at the CVS two towns over, heart pounding, hood up, sunglasses on like I was some kind of undercover celebrity. I took it in their bathroom, perched on the cold seat, hands shaking.

Two lines.

Pink.

The world narrowed to that tiny strip of plastic.

I sat there for ten minutes, underwear around my ankles, staring at it.

Then I flushed it, washed my face, and walked out into the fluorescent light.

I told Adam first.

He was in the parking lot after football practice, shoving his helmet into his bag.

I pulled him aside, my heart beating so hard I thought it might be visible.

“I’m late,” I said.

He frowned. “For what? We’re not meeting your parents until—”

“Not that kind of late,” I said. “Late-late. I took a test.”

His face drained. “Oh,” he said.

“Oh,” I echoed.

He stared at the asphalt for a long time.

“Maybe it’s wrong,” he said.

“It wasn’t,” I replied. “I checked. Like, four times.”

He swallowed. “Okay,” he said. “Okay. Okay.”

He said “okay” like if he said it enough, it would fix something.

“We’ll figure it out,” he said eventually, looking up. “We’ll talk to our parents. We’ll… I don’t know. We’ll do something.”

He hugged me.

I felt a little less alone.

That wouldn’t last.

2. The Night They Chose Their Reputation

My parents found out at the worst possible time.

I’d planned to tell them after dinner, when Dad was full and Mom was still humming from her second cup of sweet tea. I’d rehearsed the speech in my head.

Instead, they heard it from someone else.

Tammy’s boy, Cody, overheard Adam spilling to his best friend in the locker room. Cody told his mother at the beauty salon. Tammy called my mom before I’d even finished lunch.

By the time I got home from school, the house was silent and tense, like the air before a tornado.

“Jenna, living room. Now,” Dad said from the doorway, his voice clipped.

My stomach dropped.

Mom was sitting on the edge of the couch, hands folded so tight her knuckles were white. The family Bible was open on the coffee table like they were about to stage an exorcism.

“Is it true?” she asked without preamble.

I didn’t bother pretending I didn’t know what she meant.

“Yes,” I said. My voice sounded small.

Dad stood by the window, jaw clenched. “How far along?” he asked.

“Eight weeks,” I said. “Maybe nine.”

“How long have you known?” Mom demanded.

“Couple of weeks,” I said.

“You didn’t tell us,” she whispered. “You told the whole town before you told your parents?”

“I told Adam,” I said. “And Tammy heard from—”

“Adam,” Dad spat. “That boy. I knew he’d be trouble.”

“You said he was a good influence,” I said quietly.

“I said he came from a good family,” Dad shot back. “Apparently I was wrong.”

Mom wiped her eyes. “What were you thinking?” she demanded. “We raised you better than this.”

I stared at the carpet.

“I was thinking I loved him,” I said. “I still do.”

“Love,” she snorted. “You don’t know what love is. Love doesn’t do this.”

“This” hung in the air.

“This is a baby,” I said, hand involuntarily dropping to my still-flat stomach. “Your grandbaby.”

“Don’t you dare,” Dad snarled. “Don’t you dare try to spin your sin into some blessing.”

I flinched.

“I made a mistake,” I said. “We both did. But I’m not… I’m not getting rid of it.”

Mom gasped like I’d slapped her.

“We didn’t say that,” she said.

She hadn’t. Yet.

“We’re going to fix this,” Dad said. “We’ll talk to the pastor. We’ll see what our options are.”

“Our options,” I repeated. “It’s my body.”

“That body is under my roof,” he snapped. “Eating my food, sleeping in my house, bearing my name. That makes it my business.”

We argued for an hour.

About sin.

About shame.

About the church.

About what people would say.

They called Pastor Dan. He came over in his navy blazer, Bible in hand, eyes full of disappointed concern.

“I thought you were going to be my youth leader next year,” he said, sitting in our living room like it was his own.

“I still can be,” I said. “Pregnant people can love Jesus.”

He sighed. “It’s about the example you set, Jenna. The girls look up to you. You’re supposed to show them how to resist temptation, not how to give in to it.”

“I’m not a sermon illustration,” I said.

Dad raised his eyebrows. “Could’ve fooled me.”

They talked about adoption like I wasn’t in the room.

“They’ll take good care of it,” Mom said. “There are families waiting. You’ll have your life back. You can go to college. No one ever has to know.”

“No,” I said. The word felt heavy and solid in my chest. “I’m keeping it.”

They stared at me like I’d grown horns.

“Don’t be selfish,” Mom said. “Think of the baby. Think of your future husband. No good Christian man will want used goods.”

I laughed. I couldn’t help it. It came out ragged and incredulous.

“Used goods,” I repeated. “Wow. That’s what I am. Good to know.”

“That’s not what she meant,” Pastor Dan said.

“Yes, it is,” I said.

Dad’s face was red. “You brought this on yourself,” he said. “And now you’re bringing it on us. On your brother. On our church family.”

“I’m sorry I embarrassed you,” I said. “I’m not sorry about this baby.”

“It’s not a baby yet,” Mom muttered.

“It is to me,” I said.

Dad stood up, pacing.

“If you insist on keeping it,” he said, “there will be consequences.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I asked.

“You will stand before the congregation and confess,” he said. “You will tell them you have sinned. You will repent. You will step down from every leadership position. No more choir, no more youth group council. You will show that you regret what you’ve done.”

“I’m not standing up in front of everyone like some criminal,” I said.

Mom’s eyes flashed. “You already did the crime,” she said. “This is how you pay.”

“I’m not ashamed of my baby,” I said. “I’m ashamed of you.”

The room went still.

Dad’s jaw worked. “Get out,” he said.

I blinked. “What?”

“You heard me,” he said. “If you’re so grown, if you think you know better than your mother and me and Pastor Dan and the Word of God, then pack a bag and get out of my house.”

My stomach lurched.

“You don’t mean that,” I said.

He looked me dead in the eye.

“You made your choice,” he said. “Make arrangements with one of your… friends. You leave tomorrow. You are not welcome here if you insist on bringing this disgrace into our home.”

“Richard,” Mom whispered, “she’s—”

“She’s sixteen,” he said. “Old enough to lay down with a boy, old enough to live with the consequences.”

“Where am I supposed to go?” I asked, my voice breaking.

He shrugged. “If you’re so sure about this baby, I suggest you start figuring that out.”

Mom cried, but she didn’t argue.

Pastor Dan said something about tough love and prodigal children.

I went to my room and shut the door.

I packed a bag.

3. Two Weeks and a Lifetime

If you’d asked me, that night, how long it would be before I spoke to my parents again, I would’ve said a few days.

A week, tops.

I thought they’d cool down. That Mom would sneak into my room, tearfully apologize, beg me to reconsider adoption. That Dad would soften when he saw my swollen belly months down the line.

I was naïve.

I left the next morning with a backpack, a duffel bag, and a knot of fear that sat under my ribs like a stone.

Mom watched from the kitchen window as Dad walked me to the curb. He didn’t offer to drive me anywhere. He just stood there, arms crossed, as I hoisted my bag onto my shoulder.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

I’d spent half the night texting my best friend, Haley, who lived on the other side of town with a mom who worked nights and a stepdad who mostly watched TV and grunted.

“She said I can stay with them,” I said. “On the couch. For a little while.”

Dad snorted. “That place is a mess,” he said.

I nearly laughed. “Not compared to this,” I said, gesturing between us.

He shifted.

“You’re making a mistake,” he said. “You’ll realize that soon enough.”

“I’ve already made my mistake,” I said, hand drifting to my stomach. “This is me trying to do right by it.”

He shook his head.

“If you change your mind,” he said, “if you choose adoption, we’ll help you. We’ll bring you home. We’ll figure it out. But if you insist on being a single mother at sixteen…” He trailed off.

“What?” I asked. “I’m dead to you?”

He didn’t answer.

“Goodbye, Dad,” I said.

I walked away.

No one ran after me.

Haley’s couch was lumpy and her stepdad was vaguely creepy, but it was a roof.

I lasted there two weeks.

In that time, I learned just how expensive everything was when you didn’t have parents paying the bills. Haley’s mom tried, but she was barely keeping the lights on herself. I could feel the strain of one extra mouth.

“I love you, girl,” she said one night, leaning in the doorway. “But I can’t have your folks showing up here trying to cause trouble.”

“They won’t,” I said. “We’re… not talking.”

She gave me a look. “Honey, even when you’re not talking, people talk about you,” she said. “And this town? They’re talking.”

She wasn’t wrong.

I heard the whispers everywhere.

At school, in the hallways.

“She used to be so perfect.”

“I heard she did it on purpose to trap him.”

“At least it’s not me.”

Adam lasted one week after I left home.

I don’t say that to be cruel. It’s just what happened.

At first, he sent sweet texts.

We’ll get through this. I promise.

I love you.

I’m not going anywhere.

Then his parents found out.

They called my parents, of course. No one called me.

Suddenly, Adam’s texts were less frequent. Shorter.

My mom’s freaking out.

My dad says he can get a lawyer.

We need to be smart.

Then:

My parents think adoption is best.

Then:

We’re just kids, Jenna.

Then:

I can’t throw away my future.

Then, finally:

I’m sorry.

He didn’t break up with me in one message. It was a slow fade. A gradual retreat.

By the time I missed my period the second month, I was single, homeless, and very, very scared.

I started skipping lunches to save money.

I got a few shifts at the Sonic on the highway, lying about my age on the application. I worked until my back ached and my feet throbbed, smelling like fries and desperation.

I fell asleep in English class and got detention.

The school counselor, Mrs. Ramirez, called me in one Thursday.

“How are you doing, Jenna?” she asked, folding her hands on her desk.

“Fine,” I said.

She raised an eyebrow. “You’re sleeping in class, working nights, living at a friend’s house, and pregnant,” she said. “I’m going to go out on a limb and say you’re not fine.”

I looked at my hands.

“I’m managing,” I said.

She sighed. “Have your parents reached out?” she asked.

I laughed. “They told me to call them when I was ready to repent,” I said. “So… no.”

Her mouth tightened.

She slid a brochure across the desk.

“Call this number,” she said. “It’s a shelter in Indianapolis. They have programs for teen moms. They can help with housing, prenatal care, finishing school. It’s better than Haley’s couch.”

I stared at the brochure.

“A… shelter?” I asked. The word tasted like failure.

“Shelter doesn’t mean you’re a bad person,” she said. “It means you need a safe place. That’s all.”

I put the brochure in my backpack.

That night, Haley’s stepdad came home drunk and banged around in the kitchen, cursing about the electric bill. He muttered something about “extra mouths” and slammed a cabinet so hard the door fell off.

I went to the bedroom Haley and I shared and locked the door.

I pulled out the brochure.

The next day, I called.

The shelter was a converted brick school building on the east side of Indianapolis. They called it “New Horizons,” which sounded like something my youth group would’ve put on a retreat T-shirt.

It was staffed by women who looked tired but not unkind. Some of them had probably gotten pregnant in high school too.

“You’ll have a roommate,” the intake woman, Karen, said. “Curfew at ten. No drugs, no alcohol, no guests without approval. We do group counseling three times a week, job training twice. You can finish your diploma online or enroll in the alternative school down the road.”

I nodded, numb.

Karen squinted at my intake form. “Any family support?” she asked.

The word “no” felt like a pebble in my throat.

“None,” I said.

As she walked me down the hallway with its bulletin boards full of affirmations and photos of babies with chubby cheeks, she said, “You’d be surprised how many girls check that box and then end up reconnecting with their parents once the dust settles. They come around.”

I didn’t argue.

At night, in a room that smelled faintly of Lysol and baby powder, listening to my roommate snore softly in the twin bed across from mine, I held my hand over my stomach and whispered, “We’re going to make it, okay? I don’t know how. But we are.”

The thing about being sixteen and pregnant and homeless is that every day feels like walking on a tightrope over a canyon.

One wrong step and you’re done.

I went to school in the mornings, most days. Took the city bus back to the shelter. Went to group therapy where we talked about shame and fear and the future. Learned more about birth control in six weeks there than I had in all my years of “health class.”

The other girls became my weird little tribe. Megan, who had a tattoo of a sunflower and a boyfriend in county jail. Tiana, who was already someone’s mom and someone’s daughter and someone’s ex-girlfriend all at once. Rosie, who barely talked but drew beautiful pictures of babies with wings.

We watched each other’s bellies grow.

We watched each other cry.

We watched each other try.

And then one night, I woke up with cramps.

4. The Loss They Never Earned the Right to Mourn

It was three in the morning.

At first, I thought it was just the bad chili we’d had for dinner. Then the cramps got sharper. Lower.

I went to the bathroom and sat on the toilet, sweating, my heart pounding.

The pain came in waves.

“Hey,” my roommate mumbled sleepily when I came out, hunched over. “You okay?”

“I think…” I whispered, my voice shaking. “I think something’s wrong.”

We woke Karen.

She took one look at me, white-faced and clutching my stomach, and grabbed her keys.

“The ER’s ten minutes away,” she said. “Hang in there.”

I didn’t hang in.

I clung.

To the armrest. To my sanity. To the hope that this didn’t mean what I suspected it meant.

In the fluorescent glare of the emergency room, time went funny.

Nurses. Too bright lights. Questions. How many weeks? Any bleeding? Any previous miscarriages?

No.

Not yet.

Not until now.

They put me in a gown. Hooked me up to an IV. Did an ultrasound.

The monitor’s blankness was louder than anything.

The doctor came in with his “I’m about to say something bad” face.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “The baby doesn’t have a heartbeat.”

The words hit like a physical blow, even though some part of me had already known.

“No,” I said.

“I’m afraid so,” he said gently. “Sometimes these things happen. It’s not your fault.”

He sounded like he’d said it a hundred times.

It didn’t matter. It felt like my fault anyway.

I miscarried in a gray hospital room with thin walls, a curtain for a door, and a “Teen Moms Are Brave” poster on the bulletin board.

It hurt.

Physically, yes. Cramps like my uterus was trying to claw its way out.

But also in a way that felt like it carved a hollow space in my chest.

Karen held my hand.

No one else did.

The next day, when they discharged me back to the shelter, I sat on my narrow bed and stared at the wall.

“I’m so sorry,” my roommate said, hugging me carefully.

The other girls hugged me too. They said the things people say.

At least you know you can get pregnant.

You’re still young.

You can try again.

It’ll be okay.

I didn’t feel okay.

I felt empty.

They offered to call my parents.

I laughed. It came out harsh.

“They don’t want me,” I said. “They made that very clear.”

“What if they changed their mind?” Karen asked gently.

“What if they didn’t?” I said.

I didn’t call.

They didn’t know their grandchild had died.

They didn’t know their daughter had labored alone.

They didn’t know anything.

I decided they didn’t deserve to.

That night, I pulled out a notebook and did the thing I always did when life made no sense.

I wrote.

Dear Baby, I began.

I wrote him a letter.

I didn’t know he was a boy, not really. It was just a feeling. A hunch. A tiny whisper.

Dear Baby,

I’m sorry I couldn’t keep you safe. I’m sorry my body failed you. I’m sorry my parents will never know your name. I’m sorry you didn’t get to taste mac and cheese or chase fireflies or swim in the church pond that I’m pretty sure had leeches.

I wrote until my hand cramped and my eyes burned.

At the end, I wrote:

You were loved. Even if no one else knew you.

I folded the letter and tucked it under my pillow.

The next day, I went back to school.

The bump I’d barely started to show was gone.

The rumors, for the most part, weren’t.

I graduated a year later.

My parents didn’t come.

5. Building a Life Without Them

You don’t just “get over” something like that.

But you do move forward, because the alternative is curling up and letting the world roll over you.

I finished high school online through a program the shelter connected me with.

I stayed at New Horizons until I aged out at eighteen, then moved into a cramped apartment with two other former residents. We split rent and ramen and bad decisions about men.

I got my CNA certification and started working nights at St. Vincent’s, changing bedpans and taking vitals and holding wrinkled hands.

I saw a lot of beginnings and a lot of endings.

Sometimes they blurred together.

Once, I had a patient who’d lost a baby, too. She lay in bed, staring at the ceiling, and said, “Everyone keeps telling me to be grateful I can have another. But I wanted this one.”

I sat on the edge of her bed and squeezed her hand.

“Me too,” I said.

I thought about going to therapy.

I didn’t, because it cost money and I didn’t have it.

Instead, I worked. A lot.

I went to nursing school at night, slowly chipping away at my degree. I made friends who didn’t know me as “that pregnant girl from back home.” I dated a little. Carefully. Condoms and birth control and a determination not to repeat history.

I did not tell any of the guys I dated about the baby I’d lost.

That was mine.

I heard about my parents through the grapevine.

A Facebook post here. A Christmas letter forwarded by Aunt Diane there.

“Richard and Peggy are doing so well in their retirement,” Aunt Diane wrote once. “They’re busy with church and their Bible study and their new RV. It’s a shame you never write them back, Jenna. They’re still your parents.”

I stopped opening Aunt Diane’s letters after that.

When I was twenty-six, I moved to Indianapolis full-time and got a job on a pediatric floor.

I thought maybe I was punishing myself, being around kids all day. But it turned out to be… healing.

Kids are resilient. Messy. Loud. Alive.

I liked being the person who could make a scary place a little less terrifying.

I was thirty when I met Tyler.

He was six months old, red-faced and furious, in a foster crib in the corner of the unit.

“New admit,” the day nurse said, rolling her eyes affectionately. “Born addicted. Mom’s in the wind. He’s going to need a new placement when he’s medically stable. Watch your earrings; he’ll grab them.”

I picked him up.

He stopped crying.

He had a shock of dark hair and big, serious brown eyes.

“Hey there,” I murmured. “You’re a grumpy little burrito, aren’t you?”

He blinked at me.

Something in my chest that had been locked for years clicked.

I told myself it was just a nurse thing.

Attachment happens. It passes.

It did not pass.

I asked about him every shift.

When I wasn’t assigned to his room, I’d sneak in on my breaks and rock him.

On the day he was medically cleared to leave, the social worker, Maria, lingered in the doorway.

“You should foster him,” she said casually, watching me sway with him.

I almost laughed.

“Right,” I said. “Because single thirty-year-old nurses with student loans are the first on the list.”

She shrugged. “Not the first, maybe,” she said. “But you’d be surprised. We need good homes. You have one.”

I thought of my one-bedroom apartment with its thrift store couch and IKEA bookshelf.

“Jenna,” she said, softer now. “You’re already half in love with that kid. At least get licensed so you have options.”

Getting licensed was a pain.

Home visits. Classes. Fingerprints.

It was also the first time in my life that the word “home” felt like something I was building on purpose, not something that could be taken away.

Six months later, Tyler came to live with me.

The first night, he screamed for three hours.

Then he fell asleep on my chest, his tiny fist tangled in my T-shirt, drool soaking my shoulder.

I lay there in the dark, staring at the ceiling of my little apartment, and whispered, “We’re going to make it, okay? I don’t know how. But we are.”

The echo was not lost on me.

Two years after that, I adopted him.

Standing in the courtroom in a navy dress, my hand in his small one, listening to the judge say, “Congratulations, Ms. Hart, he’s officially yours,” I felt something I hadn’t felt in a very long time.

Whole.

My parents did not know.

They didn’t even know I was in Indianapolis.

As far as they were concerned, I’d vanished.

That was fine by me.

I changed my number. Blocked them on Facebook. Moved on.

Or so I told myself.

Then the universe, in all its sick humor, decided to put us back in the same state.

6. The Return

Tyler and I moved to Avon when he was eight because my job transferred me to a satellite clinic on the west side, and the rent was cheaper out there.

I liked it.

Quiet streets. Decent schools. Target fifteen minutes away.

I picked our rental house because it had a small yard and a big kitchen.

I signed the lease and moved in the same weekend.

I did not know my parents lived forty minutes away.

I might have reconsidered, if I had.

“Small world,” my coworker Cynthia said when she saw the address on my paperwork. “My cousin lives out there. Good people.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Small.”

Too small, apparently.

Someone from my hometown—some old church lady with nothing better to do than stalk people in the grocery store—spotted me at the Kroger. She told my mother. My mother told my father. They told their pastor, probably. They told everyone.

Then they got in their car and drove to my house.

And now here we were.

Them on my porch, twenty years older and still shoving God into other people’s business.

Me in my doorway, older and harder and still that scared teen somewhere under my ribs.

Tyler in the hallway, listening, because kids always listen.

“You said you wanted the truth,” I said.

My father squared his shoulders. “We deserve to know our grandson,” he said. “We’ve made mistakes, but we’re ready to make amends. The Lord put it on our hearts—”

“The Lord needed twenty years and a Kroger sighting?” I cut in. “Slow administrative process up there.”

“Don’t blaspheme,” my mother gasped.

“Don’t change the subject,” I said.

My heart pounded. My hands trembled on the edge of the door.

“The boy you just saw,” I said slowly, “is my son. His name is Tyler. He’s ten. He loves dinosaurs, hates broccoli, and thinks Minecraft is a personality trait. He’s smart and kind and stubborn.”

My mother’s face softened. “We’d love to get to know him,” she said. “We can make up for lost time.”

“No,” I said.

She blinked. “Jenna, please. We’re his family.”

I laughed. “Family,” I said. “That’s rich.”

My father scowled. “You have no right to keep him from us,” he said. “We’re his blood.”

I felt something in me snap.

“First of all,” I said, my voice low, “you lost any claim to the word ‘right’ when you kicked me out at sixteen because I wouldn’t give up my baby to preserve your place in the church directory.”

They both flinched.

“Second,” I continued, “Tyler is not your blood.”

A beat of silence.

My mother frowned. “What are you talking about?” she asked. “We know you were pregnant. We know you had the baby. Tammy saw you that one time, big as a house, at the Dollar General. She said you had a boy.”

My chest tightened.

“Yes,” I said. “I was pregnant. You got that part right.”

“So he is—” Dad started.

“No,” I said sharply. “He is not. The baby you kicked me out over? The one you were so afraid would embarrass you in front of Pastor Dan? He died.”

The word hung in the air like a bell.

My mother’s hand flew to her mouth. “What?” she whispered.

“He died,” I repeated. “I miscarried at thirteen weeks. Alone. In a shelter. In Indianapolis. While you were probably at Bible study or watching Wheel of Fortune or whatever you did back then to feel holy and busy. I went into labor, and there was no one there to rub my back or hold my hand. A social worker I’d met three weeks earlier held my hand while I lost your grandchild. And you had no idea, because you’d made it very clear you didn’t want one.”

My father swayed.

“Jenna,” he said, voice cracking. “We… we didn’t know.”

“You didn’t ask,” I said.

My mother started to cry. Not pretty movie tears—real, messy ones.

“Oh God,” she whispered. “Oh God.”

I felt a flicker of grim satisfaction. Then a wave of something like grief, old and dull and still sharp in certain places.

“How could you not tell us?” Dad demanded suddenly, his face contorting. “We’re your parents. We had a right to know.”

“You forfeited that right when you told me to pack my bag,” I said. “When you turned your back on me at the curb and watched me walk away. When you made my pregnancy about your shame instead of my life. You made your choice. I made mine.”

He shook his head, stunned.

“We thought you were… fine,” he said weakly. “We thought you were just… too proud to come home.”

“I was surviving,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

Mom wiped her eyes. “If we’d known,” she whispered. “If we’d known you lost the baby, we would’ve—”

“What?” I asked. “Taken me back? Loved me again because the evidence of my sin was gone? Let me back into the choir?”

“That’s not fair,” she said.

“It is,” I said. “It’s exactly fair.”

We stood there, three people on a porch and twenty years of hurt between us.

“The baby we kicked you out over is—” Dad swallowed hard. “Was… a boy?”

I nodded once.

“In my head, yeah,” I said. “No one ever told me, officially. It was too early. But I… I felt like he was.”

My mother made a sound like someone had punched her.

“What… what did you do?” she whispered. “With… with the…”

“The baby?” I supplied. “The fetal tissue? The ‘evidence’ of my mistake?

I looked past them, out at the street.

“The hospital took care of it,” I said. “I held him. Once. He fit in my hand. Then the nurse took him. I signed some papers. That was it. No funeral. No casserole train from church. No pastor. No grandparents. Just me and a social worker in a room that smelled like bleach.”

They both stared at me like they were seeing me for the first time.

“I’m so sorry,” Mom sobbed. “I’m so, so sorry, Jenna.”

I’d imagined that apology so many times.

Sometimes it came in the mail. Sometimes at my graduation. Sometimes in a hospital room when I was the one dying.

In none of those scenarios did it feel this… small.

“I believe you’re sorry,” I said quietly. “I also believe you’re twenty years too late.”

Dad scrubbed a hand over his face.

“And… and him?” he asked, jerking his chin toward the hallway, where Tyler was now fully eavesdropping. “Tyler. If he’s not…”

He trailed off, unwilling to finish the sentence.

“He’s my son,” I said. “Legally. Completely.”

“But not…” Mom began.

“Not biologically yours,” I said. “No. He’s adopted. He was in foster care. His birth mom couldn’t raise him. I could. So I did.”

They looked at me like I’d grown a second head.

“You adopted?” Dad said, incredulous.

“Yes,” I said. “Three years ago. Best decision I ever made.”

My mother sniffled. “But he’s not… blood,” she said weakly.

I stared at her.

“Do you hear yourself?” I asked. “You threw out your own blood because you were ashamed. And now you’re upset that the child I chose to love isn’t biologically connected to you? You don’t get to play the genetics card now, Mom. You burnt that deck.”

“We just wanted…” She trailed off.

“What?” I pressed. “A do-over? A chance to be the sweet, doting grandparents in the church bulletin? A cute little boy to sit between you on the pew and make you look like the forgiving God-fearing family that overcame hardship?”

“That’s not fair,” Dad said again, his go-to phrase when confronted with anything that made him uncomfortable.

“Maybe not,” I said. “But it’s accurate.”

“We’ve changed,” Mom whispered. “We’re not the same people we were back then.”

“Good,” I said. “Neither am I.”

“We want to make things right,” Dad said helplessly. “We can’t change what we did. But we can… we can show up now. For you. For him.”

I looked back down the hallway.

Tyler was peeking around the corner, pretending he wasn’t.

“Ty?” I said gently. “Come here a second, buddy.”

He shuffled forward, eyes wide, bare feet quiet on the hardwood.

“This is my son,” I said to my parents. “Tyler, these are… people I knew a long time ago.”

He frowned at me. “Your mom and dad?” he guessed. He’s observant. It’s one of the things I love about him and one of the things that scares me.

I exhaled. “Yeah,” I said. “These are my mom and dad. We haven’t seen each other in a very long time.”

Tyler looked them up and down like they were candidates for a job.

“Hi,” he said politely.

My mother’s face crumpled. “Hi,” she whispered. “You’re… you’re very handsome.”

“Thanks,” he said, suspicion in his voice. “Do you like Minecraft?”

Dad blinked. “I… I don’t know what that is,” he admitted.

Tyler made a face. “Then what do you guys do for fun?” he asked.

“Tyler,” I said, half amused, half mortified.

He shrugged. “You always say it’s good to ask questions,” he said.

My mother laughed, a wet, shaky sound.

“We… we read,” she said. “And go camping. And… and play cards.”

“Camping’s cool,” Tyler said. “I went once with Mom’s friend Cynthia and her kids. We roasted marshmallows but mine caught on fire and I cried.”

He said it matter-of-factly, like he trusted the world to find his meltdown funny, not shameful.

He trusted me.

“Ty,” I said gently. “Can you give us a minute? I’ll be there in a bit to finish dinner.”

“Okay,” he said. He turned back to my parents. “Nice to meet you,” he said, because I’d raised him to be polite even when people didn’t deserve it.

He padded back down the hall.

As soon as he was out of earshot, my father said, “He seems like a good kid.”

“He is,” I said.

My mother clasped her hands. “Jenna, we could… we could be good grandparents,” she tried. “We’ve learned a lot. We lead the grief support group at church now. We— We know what it’s like to lose a child.”

I stared.

“You lost a child you chose to cut out of your life,” I said. “That’s not the same.”

She winced.

“We’re trying,” she said, tears spilling. “We’re trying to do better. Isn’t that what God wants? For us to repent and change and—”

“This is not about God,” I snapped. “Stop dragging Him into your mess. This is about you wanting access without accountability. You want the photo ops, the birthday parties, the bragging rights. You don’t want to sit in the discomfort of what you did.”

“That’s not true,” Dad said. “We’ve been uncomfortable for twenty years.”

“Good,” I said. “Sit there a while longer.”

He exhaled, deflating. “Jenna,” he said. “We’re old. We won’t be around forever. Do you want your son to grow up without grandparents?”

I thought of Karen, the social worker who’d held my hand in the ER. Of Maria, who’d guided me through the foster system. Of Cynthia, who brought Tyler a birthday cake every year and yelled at rude parents in the clinic waiting room for him.

“He won’t grow up without grandparents,” I said. “He’ll grow up without you.”

They both looked like I’d punched them.

“You can’t mean that,” Mom whispered.

“I do,” I said. “Because here’s the truth, since you came here looking for it: You don’t know how to be safe for me. And if you’re not safe for me, you’re sure as hell not safe for him. I will not put my son in front of people who might use him as a prop in their redemption story and then punish him when he doesn’t act the way they think he should.”

“That’s not fair,” Dad said for the third time.

“You keep using that word,” I said, an old movie line flickering through my head. “I do not think it means what you think it means. Fair would’ve been you swallowing your pride, standing up to the church, and saying, ‘This is my daughter. She made a mistake. We love her. We’ll figure this out as a family.’ Fair would’ve been you being there when I lost the baby. Fair would’ve been you showing up when I graduated, when I got my nursing license, when I adopted Tyler. This? This is me drawing a boundary.”

“Boundaries,” Mom echoed bitterly. “Everyone’s got boundaries now. It’s the word of the year.”

“No,” I said. “Shame was the word of my year. At sixteen. Courtesy of you. This word? This one’s mine.”

We stood there, breathing, the porch hot under our feet.

My father’s shoulders slumped. He looked old. For a flicker of a second, I saw the man who’d carried me on his shoulders at the state fair, who’d taught me how to ride a bike in the cracked church parking lot.

I saw the man who’d told me to get out.

He cleared his throat.

“If we wrote,” he said slowly. “If we called. If we… came to your… your boundary line and stayed there. Is there any chance… any possibility… that someday you might let us in a little?”

The question landed oddly.

Once upon a time, I would’ve begged for that possibility.

Now, I had a kid to protect.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “Maybe. If you go to actual therapy and not just Pastor Dan’s ‘we’re all sinners’ meetings. If you stop trying to justify what you did. If you can say, without hedging, that you were wrong. Not ‘well, we did our best.’ Wrong. If you can sit with that without throwing Bible verses at it. Maybe then we can start with a coffee in a public place. Without Tyler.”

Mom sniffled. “We can do that,” she said quickly. “We can try.”

“Then try,” I said. “Somewhere else. Today is done. You need to leave.”

“We drove forty minutes,” Dad protested weakly.

“And I walked my pregnant ass out of your house with a backpack at sixteen,” I said. “You’ll survive the drive home.”

He almost smiled at that. Almost.

My mother reached out, like she might touch my arm. I stepped back.

“Not yet,” I said.

Her hand dropped.

“We love you,” she whispered.

I swallowed.

“Then you should’ve acted like it,” I said. “Maybe you still can. From a distance.”

Dad nodded slowly.

“Okay,” he said. “We’ll… we’ll go.”

They turned.

“Jenna?” Mom said, halfway down the steps.

“Yes?”

“Is it okay if I… if I think of him? The… the baby?” she stammered. “If I… if I miss him? Even though I never…” She swallowed. “Am I allowed to grieve him? Or do I not have that right either?”

The question caught me off guard.

I thought of the small, almost weightless bundle in my hands in the ER. Of the letter under my pillow.

I thought of all the ways grief could twist you up if you didn’t give it somewhere to go.

“You can grieve him,” I said softly. “But you grieve the boy you never met. You don’t get to rewrite history and pretend you were there. You weren’t. Don’t make your grief about your guilt. Make it about him.”

She nodded, tears spilling again.

“We’ll… we’ll send the therapist receipts,” Dad muttered, a hint of that old dry humor peeking through.

“Boundaries,” I said. “Remember?”

He lifted a hand in something like a half-wave.

They got in their car.

I watched them drive away, the taillights disappearing around the corner.

I closed the door.

I leaned my forehead against it.

My hands shook.

“Mom?” Tyler’s voice came from the hallway. “Are you okay?”

I turned.

He was standing there in his Sonic T-shirt, hair sticking up, controller still in his hand.

“Yeah, buddy,” I said, exhaling. “I’m okay.”

He studied my face.

“You were yelling,” he said. “I heard stuff.”

“Yeah,” I said. “We… had a big argument. About the past.”

“Are they bad guys?” he asked.

The question made me wince.

“No,” I said slowly. “They’re… people who made bad choices. People who hurt me. People who might be trying to do better now. But they’re not safe for us yet.”

He nodded like that made sense. Kids are smarter than we give them credit for.

“Do they want to take me?” he asked suddenly, his voice small. “Back? Like… like foster care?”

My heart cracked.

I knelt in front of him and took his shoulders.

“No,” I said firmly. “Tyler, look at me.”

He did.

“No one is taking you anywhere,” I said. “You are my son. I chose you. The judge signed papers. The state of Indiana printed a whole new birth certificate with my name on it. You’re stuck with me, kid. Forever. Okay?”

He studied my face like he was deciding whether to believe me.

“Okay,” he said finally.

I pulled him into a hug.

He hugged back hard.

“Are they your mom and dad?” he asked into my shoulder.

“Biologically, yeah,” I said. “But being someone’s parent is about more than biology. It’s about how they treat you. How they show up. They… didn’t do a very good job at that when I needed them.”

“Do you still love them?” he asked.

The question startled me.

I thought of my mother’s shaking hands. My father’s slumped shoulders. The part of me that still, after everything, wanted them to show up right.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “In a complicated way. Love doesn’t just… disappear. But it changes. And it doesn’t mean I have to let them hurt me again.”

He nodded.

“Like how I can love my bio mom but not want to live with her,” he said.

The room tilted slightly.

He didn’t talk about his birth mother much. We’d always left the door open for that conversation, but he usually side-stepped it.

“Yeah,” I said, throat tight. “Like that.”

He pulled back.

“Can we have mac and cheese now?” he asked.

I laughed, the sound shaky but real.

“Yeah,” I said. “We definitely can.”

As I went back to the kitchen, stirring the pot, sprinkling in extra shredded cheese like committing a small act of rebellion against every bland diet my mother had ever put us on, I felt a strange mix of emotions.

Grief. Anger. Relief.

Closure? Not exactly.

Boundaries aren’t closure. They’re doors you leave cracked or shut depending on the day.

But for the first time in a long time, I felt… steady.

I’d told the truth. The whole messy, aching truth.

I’d protected my son.

I’d chosen my family.

“Hey, Ty?” I called.

“Yeah?”

“When we go camping next month with Cynthia, you want to try s’mores again?” I asked. “We can work on your marshmallow-roasting skills. Less fire, more golden brown.”

He padded into the kitchen, eyes bright.

“Yeah,” he said. “This time I’m not gonna cry. I’m gonna tame the fire with my mind.”

“Ambitious,” I said. “I like it.”

He grinned.

We ate dinner on the couch, elbows bumping, mac and cheese bowls warm in our laps, some silly cartoon playing on the TV.

Outside, somewhere on the highway, my parents were driving back to their church and their RV and their grief.

Inside, in a small rental house with chipped paint and a stubborn front door, I sat with my son and my complicated heart.

For the first time, the space I was taking up in the world felt exactly right.

THE END

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load