I Went to School Hungry in Secret, but One Classmate’s Question Exposed Everything and Shattered Our Whole Family’s Silence

I was thirteen the year my stomach became louder than my voice.

We were so broke the numbers didn’t even make sense. Rent was always “a little short.” The light bill was “on extension.” The fridge was “we’ll see what we can do.”

Most mornings, there was just enough milk for my little brother, Eli. Mom would pour it into his cereal bowl, scrape the box to get the last few flakes, and then look up at me with those tired green eyes.

“You’re thirteen, Maya,” she’d say. “Your body can go a few hours. Eli’s still growing.”

Like I wasn’t.

I’d shrug, like it was no big deal, and say, “I’m not hungry in the mornings anyway.”

Lie.

Then I’d grab my worn-out backpack and walk to Lincoln Middle School with my stomach already complaining.

By recess, I was starving.

That was the worst part of the day.

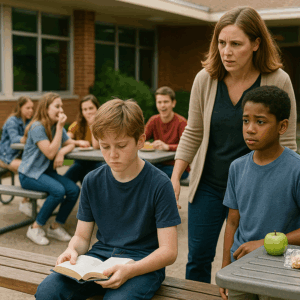

In the cracked concrete courtyard behind the school, kids would flop down at the picnic tables and on the painted benches, unzipping lunch boxes like tiny treasure chests.

Apples. Cookies. PB&Js. Thermoses that smelled like soup or pasta. Tiny bags of chips. Yogurt tubes. Capri-Suns.

I’d sit on the far end of the bench with no food in front of me, my backpack at my feet and a library book open in my lap.

If I buried my face in the pages, no one would see me not eating. If I turned a page every few minutes, maybe they’d think I was too into my book to bother with food. I’d learned to control my face, to keep it neutral even when someone peeled an orange and the sharp citrus smell made my jaw ache with wanting.

When my stomach growled, I coughed.

When it hurt so bad I felt like doubling over, I shifted in place and pretended my back was stiff.

It hurt in places hunger wasn’t supposed to hurt. Not just the physical ache, but this deep, sour kind of shame that sat under my ribs.

If anybody found out… I didn’t let myself finish the thought. I just turned another page.

That was my daily strategy.

It worked for most of seventh grade.

Until the day it didn’t.

1. The Question That Broke Everything Open

The day everything changed, the sky over our small Ohio town was that flat, metallic gray that made it impossible to tell what time it was. Early October, cold enough that we wore hoodies, not cold enough for real coats.

I had Bridge to Terabithia open in front of me, even though I’d already read it three times. It was less about the story and more about the fact that it was thick enough to hide my empty hands.

Across from me at the picnic table, my best friend, Zoe, was unwrapping a turkey sandwich from wax paper. Her mom always wrote her name on the napkin in purple Sharpie with a little heart instead of the “o.”

Z♥e.

“Ugh,” she said, peeling back the bread. “Mom put mustard again. I hate mustard.”

She took a big bite anyway.

I turned a page I hadn’t read.

“Switch with me,” our friend Jasmine said. “I’ll take mustard over this tuna travesty.”

They laughed, bartering halves of sandwiches like it was a game. Someone tossed a carrot stick. Someone else flicked a grape.

I tried to keep my eyes on the words, but the smell of turkey and mustard and tuna and mayonnaise swirled around my head like a cartoon scent cloud.

“Hey, Maya,” Zoe said suddenly. “What’d you get today?”

My heart lurched.

“Nothing,” I said without looking up. “I’m not really hungry.”

There was a beat of silence.

That was the line, the script. I’d said it a hundred times. Most days, it worked.

Today, Zoe didn’t let it go.

“Come on,” she said. “You never eat. Like, ever. You gotta be hungry sometimes.”

“I had a big breakfast,” I lied. “I’m fine.”

Jasmine snorted. “You told me this morning you were late ‘cause the power went out and you had to help your mom find the candles. How’d you cook a ‘big breakfast’ with no stove, genius?”

I stiffened.

I’d forgotten I’d said that. I’d also forgotten Jasmine actually listened when people talked.

“I grabbed something,” I muttered. “It doesn’t matter.”

Zoe’s eyes narrowed. “Do your parents not let you bring junk food or something?” she asked. “’Cause if they’re, like, super health freaks, my mom can talk to them. She’s a nutritionist now, since that online course.”

I almost laughed. My mom’s idea of nutrition was whatever was on sale in the dented-can aisle.

“I’m just not hungry,” I repeated, my voice sharper than I meant. “Can you guys drop it?”

They exchanged a look.

My stomach chose that moment to betray me with a loud, angry growl.

Jasmine’s eyebrows shot up. “Not hungry, huh?” she said.

Heat crawled up my neck.

Zoe stared at me.

“How come you never have a lunch?” she asked, quieter now. “Like, never. Did you forget it or…?”

“It’s none of your business,” I snapped.

That made her flinch.

“Whoa,” she said. “Sorry. I just—”

“I said drop it,” I repeated.

She shut her mouth.

The laughter around us from other tables kept going, but at ours, a weird tension settled.

I stared so hard at the same paragraph on the page that the words blurred.

Leslie said something magical. Jess felt something. I didn’t see it.

The shame in my throat felt like swallowed fire.

At the edge of my vision, I saw Zoe unwrap a string cheese. Peel off a strand. Hesitate.

When the bell rang, I bolted before she could say anything else.

In math class, my head throbbed. Numbers swam. Ms. Kemp’s voice sounded far away.

“The domain is all real numbers except…”

I’d barely made it through the morning on half a stale tortilla I’d found in the bread drawer and a cup of tap water.

By the time last period rolled around, I was dizzy.

My stomach wasn’t just empty; it felt like it was eating itself.

I put my head down on my desk, the cool formica a small relief against my forehead.

I didn’t realize I’d fallen asleep until someone shook my shoulder.

“Maya,” Ms. Ramirez said, her voice distant. “Sweetie, we’re done. You okay?”

I jerked upright, blinking.

The classroom was empty except for me and the teacher.

“Sorry,” I muttered. “Didn’t sleep great last night.”

She frowned.

“You’ve been nodding off a lot lately,” she said gently. “You sick or something?”

“I’m fine,” I lied. “Just… tired.”

She studied my face.

“You sure?” she asked. “You look pale.”

I shrugged.

“Do you want to go see the nurse?” she tried.

“No,” I said quickly.

The nurse would call my mom. My mom would ask why I wasn’t at home if I felt bad. The whole fragile illusion we’d built daily would crack.

“Okay,” Ms. Ramirez said. “Just… if you need anything, let me know, yeah?”

I nodded.

On the bus home, Zoe slid into the seat next to me.

She didn’t say anything at first.

We watched the houses roll by—the nice ones with immaculate lawns, the smaller ones with peeling paint, the apartment buildings with rusty balconies.

My stop was near the end.

When there were only three kids left on the bus, she finally spoke.

“Hey,” she said. “I’m sorry if I made you mad earlier.”

“It’s fine,” I said. “I was being… dramatic.”

She picked at a loose thread on her hoodie.

“Are you… like… not allowed to bring lunch?” she asked softly. “’Cause of… religion or something?”

I stared at her.

“What?” I said.

“I don’t know,” she said, cheeks flushing. “I’m just trying to understand. If you tell me, I promise I won’t tell anyone. Not even Jasmine.”

The bus hit a pothole.

I weighed my options.

If I told her part of the truth—Mom forgot, we were in a hurry—it might buy me a day or two. If I told her the whole truth, there was no going back.

My chest tightened.

“My mom just… forgets sometimes,” I said. “She works a lot. It’s not a big deal.”

Zoe looked unconvinced.

“I could bring extra,” she said. “Like, I could ‘accidentally’ pack two sandwiches, you know? And you could take one. My mom always packs too much anyway.”

Shame burned under my skin.

“I don’t need your charity,” I said.

“It wouldn’t be charity,” she said quickly. “You’re my friend. Friends share.”

“I said no,” I snapped.

She flinched again, hurt flickering across her face.

“Okay,” she said quietly. “Okay.”

We rode the rest of the way in silence.

When the bus pulled up to my corner, I stood.

Zoe grabbed my sleeve.

“Just… promise me you’ll eat something tonight,” she said. “Please?”

“I will,” I said.

I didn’t add that it might just be rice and ketchup.

I walked the three blocks to our duplex, every step heavier than it should’ve been.

Our side of the building had paint flaking off the siding and a “FOR RENT” sign that had been there longer than we had.

Inside, the apartment smelled like old coffee and damp laundry.

“Hey, baby,” Mom called from the couch, not looking up from the stack of medical bills on the coffee table. “How was school?”

“Fine,” I said, dropping my backpack. “Where’s Eli?”

“Asleep,” she said. “He was cranky. There’s leftover rice on the stove if you’re hungry.”

I opened the pot.

A thin layer scraped from the bottom of the pan, edges hard.

Better than nothing.

I scooped it into a bowl, added ketchup and a sprinkle of salt, and sat at the wobbly kitchen table.

Mom watched me.

“You okay?” she asked. “You’re awfully quiet.”

“I’m fine,” I said, shoving a forkful into my mouth so I wouldn’t have to say more.

She narrowed her eyes.

“You’re pale,” she said. “You sick?”

“I’m just tired,” I said. “School stuff.”

She sighed.

“Seventh grade is no joke,” she said. “What are they making you do now? Algebra? Back in my day, we didn’t see letters and numbers together until high school.”

I smiled weakly.

We danced around it—the hunger, the stress, the money.

Nobody said the word “poor,” like avoiding it might make it less true.

The phone rang.

Mom groaned.

“If that’s a bill collector…” she muttered, reaching for it.

“Hello?” she said into the receiver. “Yes, this is she.”

Her expression shifted from irritated to wary.

“Yes, I’m Maya’s mother,” she said. “Is… is something wrong?”

My heart stuttered.

I put my fork down.

“Yes,” she said slowly. “I can be there tomorrow morning.”

Her eyes flicked up to me, then away.

“Okay,” she said. “Thank you.”

She hung up.

“Who was that?” I asked, my voice too casual.

“School,” she said. “Vice principal. They want to ‘talk about some concerns.’”

A cold wave rolled through me.

“About what?” I asked.

She shrugged, too sharp.

“They didn’t say,” she said. “Maybe you’ve been falling asleep in class too much. Maybe your smart mouth finally got you in trouble.”

I looked down at my bowl.

I knew what it was about.

Zoe.

My stomach twisted.

I scooped another bite of rice to hide the way my hands shook.

Mom watched me, the crease between her eyebrows deepening.

“What?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“Nothing,” she said. “Eat.”

I did.

I went to bed that night with my brain buzzing and my stomach full-ish.

Sleep didn’t come easy.

Every time I closed my eyes, I saw Zoe’s face—not when she’d offered food, but when I’d snapped at her.

I saw Ms. Ramirez’s frown.

I heard the words “concerns” and “vice principal” echo like a warning bell.

Something was coming.

I just didn’t know how big it was.

2. The Argument That Went Too Far

Mom woke me up early the next morning.

“Get dressed,” she said, pulling the blanket back from my feet. “We gotta be at the school by eight.”

My heart thumped.

“What about work?” I asked, rubbing my eyes.

She glanced at the clock.

“I told them I’d be late,” she said. “My boss will survive. Apparently, my kid’s causing problems.”

The sharpness in her tone made me flinch.

“I’m not causing problems,” I said. “I don’t know what this is about.”

She gave me a look.

“Don’t lie to me, Maya,” she said. “You think I don’t know when something’s up? You barely touched your rice and you were quiet as a mouse. What did you do?”

“Nothing,” I insisted.

She snorted.

“Uh-huh,” she said. “Get your clothes on. We’ll figure it out there.”

I pulled on my jeans and my least-faded hoodie, the one that didn’t have a mysterious stain on the sleeve.

The air between us felt heavy, like the humidity before a storm.

We walked to school instead of taking the bus.

The October air bit at my cheeks. My breath puffed white.

Mom walked fast, like she was burning through nerves with each step.

At the front office, the secretary, Mrs. Lewis, gave us a tight smile.

“Good morning, Ms. Carter,” she said. “You can go right in. Mr. Collins is expecting you.”

The vice principal’s office smelled like coffee and laminate.

Mr. Collins sat behind his desk, hands folded on top of a manila folder with my name on the tab.

He was maybe in his forties, graying at the temples, with a tie that had little basketballs on it.

“Good morning,” he said. “Thanks for coming in, Ms. Carter. Have a seat.”

We sat in the two chairs across from him.

My palms were slick.

“Is my daughter in trouble?” Mom asked without preamble.

“Not in the traditional sense,” he said. “She hasn’t broken any rules. We just… have some concerns.”

There was that word again.

“About what?” Mom pressed.

He opened the folder.

“Some of Maya’s teachers have noticed she’s been falling asleep in class,” he said. “Particularly after lunch. She’s also been reporting headaches. Ms. Ramirez mentioned she’s been… unusually quiet.”

“She’s always been quiet,” Mom said. “She’s a reader. That’s not a crime, is it?”

Mr. Collins offered a small smile.

“No, of course not,” he said. “But that, combined with something that happened at recess yesterday, prompted us to check in.”

My stomach clenched.

He glanced at me.

“Maya,” he said, “do you know what I’m referring to?”

I stared at the floor.

“Zoe snitched,” I muttered.

Mom’s head snapped toward me.

“Snitched about what?” she demanded.

Mr. Collins cleared his throat.

“One of Maya’s classmates, Zoe, came to Ms. Kemp after lunch,” he said. “She was worried that Maya hasn’t been bringing a lunch. She said this has been going on for a while. Months, apparently.”

He looked at me again.

“Maya, is that true?” he asked. “Have you been coming to school without food?”

My face burned.

I wanted to disappear.

“I’m not hungry at lunch,” I said.

It sounded pathetic even to my own ears.

“Answer the question,” Mom said, her voice low.

I swallowed.

“Sometimes,” I whispered. “Sometimes we don’t have… enough. I’m fine, though. I can handle it. I don’t need—”

“You don’t need food?” Mom snapped. “Is that what you were about to say?”

I shut my mouth.

Mr. Collins held up a hand.

“No one is accusing anyone of anything,” he said. “We just want to make sure Maya is getting what she needs. We have a free and reduced lunch program—”

“I know about your program,” Mom cut in. “I signed the forms at the beginning of the year.”

Mr. Collins blinked.

“And they were approved,” he said. “Maya qualifies for free breakfast and lunch.”

My head snapped up.

“What?” I said.

I looked at Mom.

“You signed the forms?” I asked. “Since when?”

She shifted, eyes flicking between me and Mr. Collins.

“I filled them out before school started,” she said, defensive. “But I changed my mind. I didn’t turn them in.”

Mr. Collins frowned.

“May I ask why?” he said. “The program is confidential. Many students participate.”

Mom’s jaw tightened.

“I’m not letting the government feed my kid like we’re some charity case,” she said. “I can take care of my own.”

“Can you?” I said before I could stop myself.

Her head whipped toward me.

“What did you just say?” she asked, voice low and dangerous.

My pulse pounded.

“You haven’t been feeding me,” I said, louder now. “I’ve been sitting at recess with no food while everyone else eats. For months. You knew we qualified for help and you said nothing? You just let me sit there and pretend I wasn’t hungry?”

Her nostrils flared.

“Watch your tone,” she snapped.

“No,” I said.

The room seemed to tilt.

Mr. Collins looked like he wanted to shrink into his tie.

“You don’t get to tell me to ‘watch my tone’ when I’ve been starving at school,” I said. “My stomach hurts so bad sometimes I can’t think. I fall asleep in class because I’m so tired. And you knew there was a way to fix it and you just… didn’t. Because you’re too proud? Because you don’t want to be a ‘charity case’?”

Tears burned my eyes.

“Do you know how embarrassing it is?” I pressed on. “To sit there with nothing in front of you while everyone else opens their lunch boxes? To lie to your friends every day? To pretend you’re not hungry when your stomach is literally growling?”

“Maya,” Mr. Collins said gently. “Let’s—”

“And now the whole school probably thinks we’re trash,” Mom said, her own voice rising. “You telling your little friend so she can go tell the teacher, who tells the principal, who calls CPS—”

“No one has called CPS,” Mr. Collins interjected quickly. “We’re just—”

“Don’t lie to me,” Mom snapped at him. “I know how this works. You people see someone struggling and you swoop in with your clipboards and your questions, acting like you’re helping while you try to take kids away.”

“No one is trying to take anyone away,” he said.

“I’m doing the best I can,” she said, turning back to me. “I work two jobs. I sleep four hours a night. I go without so you kids can eat—”

“We’re not eating!” I exploded. “Not enough, anyway. Eli gets cereal, I get rice and ketchup and lies. You could’ve turned in the form. You could’ve let me get free lunch and breakfast and you didn’t. Because of your pride.”

The argument had become serious—so serious it felt like there was no way to bring it down.

It wasn’t like our usual bickering about chores or bedtimes.

This felt bigger. Heavier.

Like we were touching the rawest part of our life.

Mom’s eyes flashed.

“You think I like this?” she demanded. “You think I enjoy telling you no all the time? You think I don’t hate myself every time I open that empty fridge?”

“Then why didn’t you take the help?” I cried.

“Because I grew up on that help!” she shouted. “Free lunch, food stamps, charity boxes with expired canned goods and dented spam. Hand-me-down clothes from churches where the ladies would pat my hair and say, ‘Aren’t you grateful?’ while my mama stood there pretending she wasn’t dying inside. I swore to God my kids would never have to go through that.”

Her chest heaved.

“And now you’ve gone and told people,” she said, tears spilling over. “You’ve made us look like—”

“Like what?” I demanded. “Like poor people? We are poor people, Mom! Pretending we’re not doesn’t make it true. It just makes me hungry.”

Her hand flew up so fast I didn’t see it coming.

For a split second, I thought she was going to hit me.

She stopped herself, fingers trembling in the air.

The three of us stared at one another.

My heart pounded in my ears.

Slowly, she lowered her hand.

“I’m your mother,” she said hoarsely. “You don’t talk to me like that.”

“And you don’t starve me,” I responded, voice shaking. “That’s not in the job description.”

The silence that followed was so complete I could hear the hum of the fluorescent lights.

Mr. Collins cleared his throat, obviously wishing he were anywhere else.

“Ms. Carter,” he said carefully. “We’re not judging you. We know times are hard for a lot of families. That’s why these programs exist. To make sure no child sits in class hungry. Pride is… understandable. But hunger affects learning. It’s my job to make sure our students can focus. That starts with food.”

Mom swiped at her cheeks angrily.

“I don’t need your speeches,” she said.

“Maya qualifies for free lunch and breakfast,” he continued. “If you sign this form, we can start her as early as today.”

He slid a paper across the desk along with a slightly-chewed pen.

Mom stared at it like it was a snake.

“I don’t want people knowing our business,” she said.

“It’s confidential,” he said. “The cafeteria staff will know. The rest is just… a number in the system.”

She looked at me.

“So this is what you want,” she said. “To stand in that line with the poor kids and get your free tray. To let everyone see.”

“They already know something’s wrong,” I said. “Zoe knows I’m not eating. The teachers know I’m falling asleep. Which is worse? That, or me eating a sandwich in the cafeteria?”

Her mouth trembled.

She looked older than I’d ever seen her.

“Took the government food my whole childhood,” she whispered. “Still never felt full.”

Then, almost defiantly, she grabbed the pen.

Her hand shook as she signed.

The room exhaled.

“Thank you,” Mr. Collins said. “We’ll get it processed right away. In the meantime, I can give Maya a voucher for lunch today.”

He rifled through his drawer and pulled out a small red slip.

He slid it toward me like it was a ticket to some exclusive event.

I stared at it.

My throat tightened.

“Thanks,” I said, my voice barely audible.

Mom stood suddenly.

“We done here?” she asked.

“For now,” he said. “I’d like to schedule a follow-up with the school counselor. Just to make sure we’re supporting Maya—”

“We’ll see,” she said curtly.

She grabbed her purse.

“Come on,” she said to me. “You’ll be late for first period.”

I stood, my legs wobbly.

We walked out of the office in a silence that felt like shattered glass.

In the hallway, just before I turned toward my locker, she caught my wrist.

“You embarrassed me in there,” she hissed.

“You embarrassed me for months,” I shot back.

Her eyes flashed.

“We’ll talk about this later,” she said. “At home. Without an audience.”

Fear flickered through me, but it was tangled up with something else.

Relief.

Because at least now the secret was out.

3. The First Full Tray

By lunch, the whole morning felt like a fever dream.

Kids jostled in the hallway, lockers slammed, teachers barked instructions.

I moved through it all like I was underwater.

My head ached, but not the usual dull ache of hunger.

Something sharper. Emotional whiplash, maybe.

In the cafeteria, I usually veered left—outside, to my bench.

Today, I followed the line of kids to the right.

The smell hit me first.

Pizza. Green beans. Something vaguely like apple cobbler.

I clutched the red voucher in my hand, my palm sweaty around the thin paper.

“What’s that?” Jasmine asked, falling into step next to me.

“A pass,” I said.

“For what?” she asked.

“Food,” I said.

Her eyebrows shot up.

“For free?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s… a whole thing.”

“She finally admitted she’s hungry,” Zoe quipped, appearing on my other side.

I glanced at her, ready to snap, but her eyes were soft.

“Can we… talk?” she asked. “Later?”

“Maybe,” I said.

It was the closest I could get to “yes” with my pride still smoldering.

When it was my turn at the counter, the lunch lady, Mrs. Thompson, smiled.

She was always nice, but I’d never really looked at her.

“Voucher?” she asked.

I slid it across the metal ledge.

She picked up a tray and started loading it.

Pizza square. Scoop of green beans with little flecks of bacon. A carton of milk. A small salad in a plastic bowl. An apple.

The tray felt heavy in my hands.

“Heads up,” Mrs. Thompson said quietly, leaning toward me. “Breakfast, too. Eight to eight-thirty. You just give your name. We’ll get you fed.”

I nodded, my throat tight.

“Thank you,” I whispered.

She winked.

“Everybody eats,” she said. “That’s the rule back here.”

I carried the tray to our usual table like it was a museum piece.

Jasmine’s eyes widened.

“Look at you,” she said. “Joining the rest of us in carb heaven.”

“Shut up,” I muttered, but there was no heat in it.

Zoe watched me pick up the apple.

“Hey,” she said gently. “Can I say something?”

I took a bite of pizza to stall.

The cheese burned the roof of my mouth. I didn’t care.

“You told,” I said after I swallowed. “To Ms. Kemp.”

She winced.

“Yeah,” she said. “I did.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because you were clearly lying,” she said. “Like, badly. And you were falling asleep in math and looking like you were gonna pass out in PE and… I dunno. I freaked out. I thought maybe something worse was going on. I told Ms. Kemp I was worried about you. Not like, ‘Oh my God, look at poor Maya,’ but like… ‘My friend seems off. Please help her.’”

I stared at the tray.

“It wasn’t your secret to tell,” I said.

“I know,” she said, cheeks flushing. “I’m sorry. I just… I didn’t know what else to do.”

The thing was, she wasn’t wrong.

I’d been falling apart.

The old anger flared, but it flickered against the memory of her offering extra food and me throwing it back in her face.

“It sucks,” I said finally. “Having people know. But… I’m not… mad. Not really.”

Her shoulders sagged in relief.

“So we’re… okay?” she asked tentatively.

I looked at her.

My best friend, who’d invited me to every birthday party, who’d shared all her secrets, who’d never once acted weird about the fact that my house was smaller and louder and messier than hers.

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re okay.”

She grinned.

“Cool,” she said. “Because I was worried I’d have to find a new partner for the science fair, and you know anyone else would drag down my GPA.”

I snorted.

“Wow,” I said. “Way to make it about grades.”

We laughed.

It felt like a pressure valve had released just a bit.

I picked up my fork and took a bite of green beans.

They were mushy.

They were perfect.

For the first time in months, my stomach didn’t hurt by the end of the day.

My head felt clearer.

I raised my hand in science class.

I didn’t fall asleep in social studies.

When I got home, my body felt… calibrated. Like someone had adjusted the dials.

Mom wasn’t on the couch.

She was at the kitchen table, a stack of paperwork in front of her.

“What’s all that?” I asked cautiously.

She didn’t look up.

“SNAP forms,” she said.

My chest tightened.

“Food stamps?” I asked.

She sighed.

“Yeah,” she said. “The counselor called me after our little… scene this morning. Talked to me like I wasn’t a complete failure. Said there’s this emergency thing we might qualify for. I figured since I already humiliated myself once today, might as well go for the full set.”

Her attempt at a joke landed lopsided, but it was something.

I pulled out a chair.

“Do you… want help?” I asked.

She glanced up, surprised.

“You know your social?” she asked.

“Yes, Mom,” I said. “I’m not five.”

“Okay, smarty pants,” she said, sliding a form toward me. “Fill in your part.”

We worked in silence for a while, the scratch of our pens the only sound.

Halfway through, she sat back.

“Listen,” she said. “About earlier.”

I stiffened.

Here it comes.

“The argument got… out of hand,” she said. “I shouldn’t’ve raised my hand at you. I didn’t hit you, but I wanted to, and I’m not proud of that. I was scared and defensive and… ashamed. Not of you,” she added quickly. “Of me. Of the situation. I took it out on you. That’s… not fair.”

I blinked.

I’d expected more anger. Maybe some grounding. Not… this.

“I shouldn’t have yelled at you like that,” I admitted. “In front of Mr. Collins. I made you look bad.”

She snorted.

“I’ve looked bad before,” she said. “Way worse than a school meeting. Besides, you weren’t wrong.”

I stared at her.

“I wasn’t?” I asked.

“You needed food,” she said. “I let my pride get in the way. That’s on me. I thought I was protecting you from… shame. From being ‘the poor kid.’” She shrugged. “Turns out, you were already carrying that around, huh?”

My throat tightened.

“Yeah,” I whispered.

She reached across the table and squeezed my hand.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly. “For making you choose between being hungry and pretending everything was fine.”

Tears stung my eyes.

“I’m sorry I told,” I said. “I mean, I didn’t tell-tell. Zoe did. But… I’m sorry it blew up like that.”

She shook her head.

“Maybe it needed to,” she said. “Sometimes things gotta explode before you can put them back together right.”

We sat there, our hands linked over government forms, in a kitchen that smelled like nothing because we had nothing cooking, and for the first time, I felt like we were on the same side.

Not me against her. Not her against the world.

Us. Against the problem.

Maybe we’d still lose sometimes.

But at least we’d be losing together.

4. Years Later, at the Other End of the Table

I didn’t think that day in the vice principal’s office would follow me forever.

But it did.

Not like a ghost haunting me, not all the time.

More like a compass, pointing in a direction even when I forgot I was following it.

Ten years later, I sat at another laminate-topped table in another school office.

This time, I was on the other side.

“Ms. Carter?” the mom across from me said. “You listening?”

I blinked, pulling myself back.

“Yeah,” I said. “Sorry, Ms. Rodriguez. I was… remembering something.”

She frowned.

My nameplate on the table said: Maya Carter, School Social Worker.

Her name on the file said: Elena Rodriguez.

Between us sat a stack of forms—lunch applications, healthcare waivers, information about the local food pantry.

“He won’t eat in front of the other kids,” she said, gesturing toward her son, Gabriel, a small, skinny boy with huge brown eyes and a Spider-Man T-shirt. “He says he’s ‘fine.’ He says he’s not hungry. But I see him at home. He’s… so hungry.” Her voice cracked. “I don’t know what to do.”

I looked at Gabriel.

He was thirteen.

I knew that look.

The mix of defiance and embarrassment. Pride and need.

“Hey,” I said softly. “You like Spider-Man?”

He shrugged.

“He’s okay,” he muttered.

“You know what his superpower really is?” I asked.

He looked up, suspicious.

“Climbing walls?” he guessed.

“Not that,” I said. “It’s asking for help.”

He frowned.

“That’s dumb,” he said. “He’s strong.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Physically. But emotionally? His whole thing is, when he tries to do everything alone, it goes wrong. When he works with other people, it goes better.”

He considered that, his nose scrunching.

“My mom says if I tell the school we don’t have money, they’ll think we’re… losers,” he mumbled.

Ms. Rodriguez sucked in a breath.

“I did not say that,” she protested.

He shot her a look.

“You said they’d look down on us,” he said. “Same thing.”

Her shoulders slumped.

“Okay,” she said. “Maybe I said that. I didn’t mean… losers. I meant…”

“Poor,” I finished for her.

She flinched.

That word still had teeth.

I leaned forward.

“When I was your age,” I said to Gabriel, “I used to go to school with no lunch.”

He stared at me.

“For real?” he asked.

“For real,” I said. “I’d sit outside and read during lunch so people wouldn’t notice I wasn’t eating. My stomach growled so loud I thought people could hear it. One day, my friend told a teacher. The school called my mom in. My mom got really mad. She grew up on free lunch and food stamps and hated the way people treated her. She didn’t want that for me.”

“What happened?” he asked.

I smiled.

“We had a big fight in the vice principal’s office,” I said. “It got… pretty serious.”

I met Ms. Rodriguez’s eyes.

“She thought the school would judge her,” I continued. “That they’d call child services. That they’d say she was a bad mom. But the vice principal said something I’ve never forgotten.”

“What?” Gabriel asked, leaning forward despite himself.

“‘That’s why these programs exist,’” I quoted. “‘To make sure no child sits in class hungry.’”

He chewed on that.

“Did people make fun of you?” he asked quietly. “When you started getting free lunch?”

“Some kids tried,” I said. “But most of them were too busy worrying about their own stuff. And the kids who mattered? They were just glad I wasn’t falling asleep in class anymore.”

Ms. Rodriguez stared at me.

“Did you… hate your mom?” she asked. “For not taking the help sooner?”

I thought about that day. About the pain in my mother’s eyes. About her hand hovering in the air. About the apology at the kitchen table that night, over SNAP forms.

“No,” I said. “I was angry. I felt neglected. But I also understood later that she was carrying her own shame. Her own memories. She wasn’t trying to hurt me. She was trying to protect me… in the wrong way.”

I looked at her.

“You’re not a bad mom,” I said. “You’re a mom in a bad situation, trying to protect your kid from a world that can be cruel to people who don’t have money.” I slid the lunch form toward her. “Let me help you protect him… in a better way.”

Her eyes filled.

“Will they judge us?” she whispered.

I thought of Mrs. Thompson in the cafeteria. Of how she’d said, “Everybody eats. That’s the rule back here.”

“Some people might,” I said honestly. “People always have opinions. But the people who matter? The lunch staff. The teachers who see him falling asleep. Me. The principal. We just don’t want him to go hungry. That’s it.”

Gabriel stared at the form.

“I don’t want to be ‘the poor kid,’” he said.

“You already are,” I said gently. “Whether you fill this out or not. The difference is, this way, you’ll be ‘the kid who eats lunch.’”

He huffed out a laugh.

“That’s a lame superhero name,” he said.

“The best ones are,” I said. “They’re the ones who don’t sound cool in movies, but they save lives in real life.”

He looked at his mom.

“Can we… do it?” he asked.

She nodded, tears slipping down her cheeks.

“Yeah,” she whispered. “Yeah, baby. We can do it.”

She picked up the pen.

I watched her sign, feeling something in my chest unclench.

When they left, voucher in hand, I sat there for a minute, letting the quiet settle.

My phone buzzed.

A text from Zoe.

Zoe: Hey. Our ten-year reunion is in two weeks. You going?

I smiled.

Zoe and I had stayed friends all the way through high school. She’d been at every crisis, every milestone. Her family had fed me more nights than I could count.

Me: I guess I have to. Someone has to make fun of your haircut.

Three dots appeared.

Zoe: Rude. Also, do you ever think about that day? With the lunches?

I leaned back.

Me: Today? All the time. I’m literally signing lunch forms for kids.

Zoe: Ofc you are. Thirteen-year-old you would be proud. Also, I’m glad you yelled at me for telling. But I’m also glad I did.

Me: Me too. Don’t get a big head.

Zoe: Too late. See you at the gymnasium of horrors.

I laughed, the sound bouncing off the office walls.

5. Going Back

The Lincoln Middle “Ten-Year Reunion” was really just an excuse for the school district to throw a fundraiser.

They sent out invitations to everyone who’d been in the graduating eighth-grade class. Most of us had scattered—to colleges, jobs, different cities.

A surprising number came back.

The gym smelled exactly the same: floor polish, sweat, and faintly stale popcorn.

There were folding tables with chips and store-brand soda, a photo slideshow looping on the big projector screen, and a DJ playing songs we’d danced to at the eighth-grade “formal.”

“Oh my God,” Jasmine said, appearing at my elbow. “Look at you, Ms. Social Worker. You look all professional and stuff.”

“You look like you own a salon,” I said.

“I do,” she said, flipping her hair. “Well, half of one. You should come in. That ponytail is a cry for help.”

We laughed.

A familiar voice piped up behind me.

“Don’t listen to her,” Zoe said. “Your ponytail is iconic.”

She hugged me.

For a few minutes, we were thirteen again, gossiping by the bleachers.

“Did you ever think we’d be here?” she asked, taking a sip of neon-red punch. “Like, back in this same sweaty gym, but as actual adults?”

“Never,” I said. “I thought I’d graduate and never think about this place again.”

She laughed.

“Yet here you are, working in a school,” she said. “The call was coming from inside the house this whole time.”

We wandered past the tables of yearbooks and photos.

There we were in seventh grade.

My hair too frizzy. Zoe’s hoodie too big. Jasmine mid-eye roll.

I stared at a picture of us at a picnic table in the courtyard.

Zoe with a sandwich.

Jasmine with a juice box.

Me with a book in my lap and nothing on the table.

“That was the day,” Zoe said softly, nodding at the photo.

“Yeah,” I said.

“You were so mad at me,” she said. “On the bus.”

“I was hungry,” I replied. “Hungry and ashamed. It’s a dangerous combo.”

She slipped her arm through mine.

“You know,” she said, “my mom told me later she was proud of me. For telling. I didn’t get that then. I just thought I’d betrayed you.”

“I felt betrayed,” I said. “But I also… needed it. Even if I couldn’t admit it yet.”

We stood there in silence for a moment, looking at our younger selves.

“I’m glad we had that argument,” I said.

“Which one?” she asked. “We had many.”

“The first one,” I said. “When you wouldn’t drop it. You asked the question that blew everything up. And then the argument with my mom that got… serious.”

She winced.

“I was lowkey terrified of your mom after that,” she said. “She stormed past me in the office and I thought she was going to throw a chair. Now that I work with adults, I get it. Humiliation makes people… volatile.”

“Yeah,” I said. “She’s calmer now. Still loud. But calmer.”

“How is she?” Zoe asked.

“Good,” I said. “She’s managing the night shift at the grocery store. Knows all the regulars. She’s like the unofficial mayor of Aisle Five.”

Zoe smiled.

“She still get mad about the government cheese?” she asked.

“Less mad,” I said. “She volunteers at the food pantry sometimes. Says she’s trying to ‘fix the system from the inside.’”

“Sounds like someone else I know,” she said.

We moved on, saying hi to old classmates.

Hunter was there, shockingly kind now, working as a mechanic.

Ms. Ramirez, my English teacher, hugged me so hard I nearly choked.

“You always did like stories,” she said. “I’m glad you’re helping kids write better ones.”

Later, when the crowd thinned, I stepped out into the courtyard.

The picnic tables were still there.

The paint on the benches was more chipped. The trees were a little taller.

I sat in the spot where I’d hidden behind my book.

For a second, I could almost hear the echoes of kids opening lunch boxes, the crinkle of wrappers, the rumble of my own stomach.

In my mind, I saw thirteen-year-old me sitting where I was sitting now.

Thin. Tired. Trying so hard to be invisible.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered to her.

Sorry for how hard it was.

Sorry it took so long for anyone to notice.

Sorry for how much shame she carried that wasn’t hers.

And also: “Thank you.”

Thank you for surviving.

Thank you for reading instead of fighting.

Thank you for yelling when it finally became too much.

“Hey,” someone said behind me. “You hiding from the bad DJ?”

I turned.

Mr. Collins stood in the doorway, a little heavier, a little balder, but still with the same basketball tie.

“Vice Principal Collins,” I said, standing. “I’m not terrified of you anymore.”

He laughed.

“I’m just Joe now,” he said. “You’re the one with the intimidating job.”

We sat.

“I heard you’re working at Eastside High,” he said. “School social worker. Taking on the world.”

“Trying,” I said.

He looked around the courtyard.

“Do you ever think about that day?” he asked.

“All the time,” I said. “Do you?”

He nodded.

“I’ve sat in that office with a lot of families,” he said. “But that argument between you and your mother… that one stuck with me.”

“It got… intense,” I said.

“I thought she was going to hit you,” he admitted.

“So did I,” I said. “She almost did. But she didn’t.”

“That was the moment I knew she was a good mom,” he said.

I stared at him.

“Most people judge her for the opposite,” I said. “For not feeding me enough.”

He shook his head.

“Good parents make bad choices sometimes,” he said. “Pride. Fear. Trauma. Call it what you want. But when someone raises their hand and then stops short? When they sign the form even though it burns?” He shrugged. “That’s the line, right there. She stepped over it. In the right direction.”

My chest tightened.

“Thanks,” I said.

He glanced at me.

“You turned out okay,” he said. “More than okay.”

“Still working on it,” I said.

We sat there for a moment, two people who’d once been on opposite sides of a desk, now just two adults in a courtyard.

“Hey, Joe?” I asked.

He raised an eyebrow.

“Yeah?”

“Back then,” I said, “did you call CPS?”

He smiled wryly.

“No,” he said. “We did what we were supposed to do. We documented. We followed up. We offered resources. We watched. But we didn’t call for removal. You weren’t being abused. You were being… failed by a system that makes it so easy to fall a little short, then a little more, until you’re out of options but too ashamed to admit it.”

I nodded.

“I used to think you were the enemy,” I said.

“I used to think I was the hero,” he replied.

We both laughed.

“Turns out,” he said, “we were both just people trying not to mess up too badly.”

The sky overhead was that same flat Ohio gray.

But I felt lighter than I had in a long time.

On my way out, I stopped by the parking lot.

My mom was waiting in her beat-up Corolla, scrolling her phone.

She’d insisted on driving me, despite my protests that I was a grown woman with my own car.

“Hop in,” she said when she saw me. “How was Memory Lane?”

“Dusty,” I said, sliding into the passenger seat. “But… good.”

She pulled out of the lot.

We passed the playground.

The swings creaked in the wind.

“You know what I remember most?” she said suddenly, eyes on the road. “From back then?”

“What?” I asked.

“Coming home after that meeting,” she said. “Sitting at the table. Filling out those food stamp papers with you.”

She smiled a little.

“I felt like such a failure,” she said. “Needing my thirteen-year-old to help me. Letting the school see our business. Signing over my pride on a dotted line.”

She glanced at me.

“But now, when I think about it… that’s when everything shifted,” she said. “That’s when we stopped pretending. When we started… telling the truth.”

My throat tightened.

“Yeah,” I said. “Me too.”

She reached over and squeezed my knee.

“Look at you now,” she said. “Helping other people fill out their papers. You took our mess and turned it into something good.”

I shrugged, blinking fast.

“Just trying to make sure some other kid doesn’t have to pretend they’re not hungry,” I said.

She nodded.

“Good,” she said. “Make some noise.”

We drove the rest of the way home in companionable silence.

The world still had bills and rent and food deserts and bureaucrats.

Kids still sat at picnic tables with empty hands.

Parents still wrestled with pride and shame and the fear of being judged.

But somewhere, in a cafeteria, a lunch lady was quietly saying, “Everybody eats. That’s the rule back here.”

Somewhere, a teacher was catching a kid nodding off and thinking, Maybe it’s not laziness. Maybe it’s hunger.

Somewhere, a social worker was sliding a form across a desk and saying, “You’re not a bad parent. You’re a parent who needs support.”

And somewhere inside me, the thirteen-year-old who’d hidden behind her book at recess was finally sitting down with a full tray, not pretending anymore.

That didn’t fix everything.

But it was a start.

THE END

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load