Outgunned, Outranked, but Not Outwitted: How a Nervous Student With Nothing but ‘Rabbit Tricks’ Outsmarted a Legendary German Sniper With 400 Confirmed Kills and Saved an Entire Company

By the time the German sniper set up on the ridge above the village, most of the men in Second Platoon already knew his reputation.

They’d heard the rumors. Four hundred confirmed kills. A veteran from the Eastern Front, brought west to “stiffen” the defense. Invisible. Patient. The kind of enemy who turned every open window and dark doorway into a question mark.

Private Tom Jensen knew exactly two things about him:

One, the sniper was somewhere out there, watching.

Two, Tom was definitely not the person who should be trying to deal with that.

He wasn’t supposed to be here at all.

Six months earlier, Tom had been a lanky engineering student at a small college in Ohio, worrying about exams and whether the girl who borrowed his notes might also borrow an interest in him.

Now he lay flat in the cold grass on a hillside in France, helmet pressed against the dirt, trying not to breathe too loud.

“Rabbit,” Sergeant Cole whispered beside him. “Your turn.”

Tom grimaced. “Can we not call me that right now?” he muttered.

“Kid, you know the rules,” Cole said. “You’re quick. You’re small. You think sideways. You hop. You’re Rabbit. Besides, your ‘rabbit tricks’ are why you’re still alive.”

Tom swallowed, eyes flicking toward the village below.

The place had probably been pretty once—red roofs, stone walls, a church tower with a bell that hadn’t rung in months. Now, shattered glass glittered in the streets. Smoke curled from a ruined barn. Shell holes pocked the road.

Somewhere among those broken shapes, the sniper watched the approaches.

That morning, when First Squad had tried to move across the open lane by the cemetery, three shots had cracked out. Three men had gone down. No one had seen where the fire came from.

After that, everyone got very careful.

The company commander, Captain Harris, had called the platoon leaders together behind a half-collapsed wall.

“We’ve got to get through that village,” he’d said, jaw clenched. “Division wants the crossroads by nightfall. But I’m not feeding good men into a shooting gallery.”

“Artillery?” someone had suggested.

Harris had shook his head. “We start dropping heavy shells and we might take down half the village. There are still civilians in there. And I’m not going to call in a whole battery to deal with one rifle, even if that rifle’s got a big reputation.”

He’d looked at Cole then, eyes measuring.

“You’ve got that student,” Harris had said. “The one who keeps coming up with… creative ideas. Jensen.”

Tom, standing a little behind the others, had tried to look smaller.

Cole had shrugged. “He’s not exactly an expert, sir. More like a collection of weird habits.”

“Weird habits are fine,” Harris had said. “As long as they keep my people alive.”

So now Tom lay in the grass, heart jackhammering, trying to decide if being known for “rabbit tricks” was better than being anonymous and safe.

“Remind me why this is my turn?” he whispered.

Cole kept his eyes on the village, binoculars glued to his face. “Because you’re the only one who’s managed to cross that orchard twice today without taking a bullet,” he said. “And because you’re the one who said, and I quote, ‘This isn’t magic. He’s following patterns.’”

Tom made a face. “I hate when you listen to me.”

“No, you don’t,” Cole said. “You just hate when it leads to work.”

Tom’s mind flashed back to the orchard.

They’d been pinned for nearly an hour, unable to move along the main road without drawing fire. The sniper had taken a shot at a helmet someone raised on a stick and had hit it dead center at a ridiculous distance.

“We could go around,” Tom had suggested then, pointing to the trees. “Through the orchard.”

The others had looked at the open spaces between the trunks, the patches of sun and shadow.

“He’ll see us,” one had said. “We’ll be like ducks in a shooting gallery.”

“Not if we don’t move like ducks,” Tom had said.

He’d grown up hunting rabbits with his grandfather in the Ohio countryside. He’d watched how they moved—never in a straight line, never at a steady pace. A hop here, a dart there, a pause with ears up. They’d freeze in plain sight and somehow not be seen because the eye expected motion, not stillness in the wrong place.

“You ever try to shoot a rabbit at distance?” he’d asked. “You think you know where it’s going, then it zigzags. You fire where it should be, not where it actually is.”

“You suggesting we start hopping?” someone had cracked.

“Kind of,” Tom had said.

He’d grabbed a couple of rocks, tossed them one way, then another, watched how heads turned, how even his own eyes tracked the wrong thing.

“Decoys,” he’d said. “Movement here, noise there. We move when his eye is somewhere else. One at a time. Never straight, never predictable. Rabbit tricks.”

Cole had watched him, one eyebrow raised.

“Okay, Rabbit,” he’d said finally. “Show me.”

So Tom had gone first.

He’d walked into that orchard with every nerve screaming, spotting the likely lines of sight, the angles. He’d tossed a rock into a patch of brush, then dashed two steps the other way, dropped flat, waited.

No shot.

He’d moved again, this time in a different rhythm—short step, long step, sudden crouch. A burst of automatic fire from farther down the line had distracted the sniper for a heartbeat. Tom had used that gap to slide behind a tree, then another.

It had taken him fifteen of the longest minutes of his life, but he’d made it all the way across. Then he’d done it again, coming back, sketching the sniper’s likely positions in his head.

“He favors the left,” Tom had said afterward, breathless, pointing to the ridge. “Two or three strong shooting angles that direction. He’s not everywhere. He’s somewhere.”

Cole had looked at him with something like respect.

“Not bad, Rabbit,” he’d said. “Now we just have to figure out how to turn your rabbit tricks into fox hunting.”

Which led, eventually, to this: Tom lying in the grass with a coil of field telephone wire, three empty ration tins, a pocket mirror, and a canteen full of small stones.

“How many confirmed kills did they say?” Tom asked, stalling.

“Does it matter?” Cole said.

“Just curious,” Tom replied.

Cole sighed. “Four hundred.”

Tom closed his eyes for a second.

“Okay,” he said. “Then let’s not be four-oh-one through four-oh-three.”

The plan, like most of Tom’s ideas, started stupidly simple.

“The problem,” he’d told Cole and the others around a quick sketch in the dirt, “is not that we can’t see him. It’s that he’s better at seeing than we are.”

“He’s also better at hitting what he sees,” someone had said dryly.

“Exactly,” Tom had replied. “So we don’t give him what he’s expecting to see.”

He’d drawn the ridge, the village, their own positions.

“He’s up here somewhere,” Tom had said, tapping the ridge line. “High ground, good concealment. He’ll have at least two firing positions he can move between, maybe three. A self-respecting sniper doesn’t just dig into one hole and stay there. He’ll shoot, shift, shoot again. We saw that by the angle of the hits.”

Cole had grunted. “We also saw that by getting holes punched near our ears.”

“Right,” Tom said. “So. We can’t send a squad to flank him; he’ll pick them off. We can’t drop big shells because there are still people in those houses. We need him to show us where he is without him knowing he’s doing it.”

Captain Harris had frowned. “How do you suggest we do that?” he’d asked. “Ask nicely?”

Tom had smiled nervously. “Something like that,” he’d said. “We… annoy him. We give him targets that aren’t what they seem. We fake patterns. We let him think he’s one step ahead until he’s actually half a step behind.”

“Rabbit tricks,” Cole had murmured.

Tom had nodded.

“Rabbits don’t outrun everything,” he’d said. “They out-think predators for just long enough to get away. They flick their tails to draw a shot, then dart somewhere else. They freeze when they should run, run when they should freeze.”

He’d shrugged at the skeptical looks.

“Look,” he’d said, “I’m not saying I’m smarter than a guy with four hundred confirmations. I’m saying he’s used to people doing certain things. We make him see what he expects to see… while we’re really somewhere else.”

Captain Harris had tapped the tip of his pencil against his teeth, thinking.

“All right, Private,” he’d said. “You’ve got ten minutes to turn your rabbit stories into something I can send men to do.”

Tom had almost said, “Actually, I meant me,” then decided he’d better own it.

So he explained:

Three decoy helmets on sticks in different places, raised in a deliberate, repeating pattern. Every few minutes, one would pop up, then another, then the third, mimicking the cautious behavior of men trying to peek. The sniper, watching, might see a pattern. He might adjust his aim, try to time his shots.

They’d string a thin line of field phone wire between the sticks, so one man—operating from cover—could control all three helmets from a distance, without exposing anyone.

They’d scatter the empty ration tins with pebbles in them along the ditch, then, at irregular intervals, yank another wire to make one rattle, like someone crawling. Not enough to pinpoint, just enough to annoy.

And Tom, using his grandmother’s compact mirror and a decent understanding of geometry, would try to bounce a tiny flash of light off the windows of the houses at different angles, looking for the telltale glint of optics returning the bounce.

“You’re going to play tag with a professional sniper using a shaving mirror,” someone had muttered.

“A student with a mirror,” Tom had corrected. “Big difference.”

Cole had looked at the sketch one more time.

“Okay,” he’d said. “We do it. But I’m not sending anyone else to work your puppet show. This is your idea, Rabbit. You run the strings.”

Tom had opened his mouth to argue, then shut it again.

He’d made the plan. Whether it terrified him or not, it should be him out there.

Which was how he ended up here, feeling every heartbeat in the fragile skin of his neck as he lay in the grass with wires looped around his fingers.

“Remember,” Cole whispered, low so his voice wouldn’t carry. “You hear a shot crack close, you stay down. Don’t lift your head to check where it came from.”

“Do I look that eager to peek?” Tom whispered back.

“You look like a curious student,” Cole said. “Curious students get into trouble.”

Tom would’ve rolled his eyes if he hadn’t been afraid of brushing his helmet against something that might reflect light.

The three helmet decoys were already in place, their sticks anchored in the shallow ditch that ran parallel to the lane. From his position behind a thick clump of brush, Tom could see all three if he glanced just right: one near a broken gate, one in a dip by the old stone wall, one closer to a rubble pile.

He tugged gently on the wire for the gate helmet.

It rose an inch, then dropped.

Nothing.

He waited thirty seconds. Tugged the one by the wall.

Up, down.

Still nothing.

“How long you think?” he murmured.

“As long as it takes,” Cole answered. “Remember, this guy waits. You rush, you lose.”

Tom waited.

Waves of silence rolled over the field. Somewhere a bird called, oblivious. Farther back, he heard the low murmur of men talking, the occasional clank of gear.

The sniper did nothing.

Good, Tom thought. Or bad. Hard to tell yet.

He tried again, this time in the order gate–rubble–wall. Same motions, same tentative peeks, as if three different nervous men tried their luck.

On the third sequence, the world split.

Crack.

The sound tore through the air, followed almost instantaneously by a sharp whip of air somewhere above Tom’s head.

He flinched, flattening instinctively, pressing himself into the earth. His heart jumped into his mouth.

Cole didn’t move.

“Which one was up?” he asked calmly.

Tom forced his brain to work.

“Gate,” he whispered. “First.”

“Pattern,” Cole murmured. “He’s seeing it.”

Tom swallowed hard. “I’ll change it.”

He waited, counting slowly to forty, then raised the helmet by the rubble pile halfway, held it for a second, dropped it, then popped the wall helmet quickly up and down.

Crack.

This time, he heard the passing bullet closer to the rubble pile. Chip of stone flew from the wall.

“Okay,” Tom said through clenched teeth. “He’s on us.”

“And we’re on him,” Cole said. “You see anything with that mirror yet?”

Tom pulled the compact from his pocket, thumb rubbing the worn silver cover.

He’d practiced with it the night before, bouncing tiny flashes of light off a spoon, a canteen, a window. If a scope or binocular lens were aimed his way, he might—might—catch a faint, unusual glint.

It wasn’t much. But it was something.

Now he opened it carefully, angling the mirror low, catching a slice of pale sky. He rotated it slowly, letting a tiny shimmer of light slide across the windows of the village houses like an invisible searchlight.

One house. Nothing.

Another. Nothing.

Third: a faint flicker from a second-story window, but that could have been broken glass.

He shifted slightly, letting the angle change by inches.

A breath of light came back from the church tower. Again, could be glass.

Then, as he brushed the mirror through a narrow slice between two chimneys on the ridge, he saw it—a quick, sharp pinprick flash not quite like the others. Too round. Too concentrated.

His skin prickled.

“There,” he whispered.

“Where?” Cole asked.

“Ridge,” Tom said. “Between the tall chimney and the bare tree. There’s a rock outcrop with a… kind of notch.” He swallowed. “He’s in that notch.”

Cole raised his binoculars, slow as molasses, careful not to let the lenses glitter. He stared where Tom directed.

“Can’t see him,” Cole said after a moment. “Can see the rocks. Nothing else.”

“That’s the point,” Tom said. “He can see us. We can’t see him. But we know where the hole is now.”

Cole grunted. “You sure that flash wasn’t just…?”

“It happened twice,” Tom said. “Once when I went too low, once when I went too high. Scope glass, catching just a hair of light when he moved.”

Cole thought for a moment.

“Okay, Rabbit,” he said. “You’ve poked the fox. Now what?”

Tom looked at the wires in his hands, at the village, at the ridge.

“Now we teach him to chase,” he said.

What Tom understood, better than he liked, was that experts weren’t just skilled—they were also proud.

A man with four hundred confirmed kills didn’t see himself as lucky. He saw himself as precise. Effective. Smarter than the people on the other end of his rifle.

Tom’s plan leaned on that.

“He thinks we’re scared,” Tom explained to Captain Harris a few minutes later, when they’d crawled back to the crude command post behind the stone wall. “And we are. But he also thinks we’re predictable. We peek, he shoots. We stick a helmet up, he punishes it.”

Harris’s face was lined with dust and fatigue. “He’s not wrong so far,” he said.

“We change the script,” Tom said. “We make him think he’s figured us out. We let him hit helmets, not heads. We let him feel like he’s breaking us down. Meanwhile, we get a fix on his angles. We watch where his shots come from, not just that they came.”

“Then what?” Harris asked. “We can’t exactly walk a mortar barrage right onto that notch. Too close to the village roofs.”

“Not mortars,” Tom said. “Smoke.”

Cole blinked. “Smoke? You think he’s going to cough himself out of position?”

Tom shook his head. “No. We use smoke to block what he thinks he wants to see, and to hide what we really care about.”

He pointed at the sketch again.

“We put smoke between him and our decoys,” Tom said. “Not thick enough to make him completely blind—just enough to make him nervous. He’ll either wait it out or shift to a new spot to get a better angle.”

“And when he shifts?” Harris asked.

“We’re ready,” Tom said. “We won’t have a lot of time. But if we know where he is now, and we can force him to move, we can narrow down where he goes next. Like narrowing corridors in a maze.”

Harris looked unconvinced. “That’s a lot of ifs,” he said.

Tom didn’t argue. It was.

But they were running out of options.

“With respect, sir,” Tom said, “if we wait for a perfect solution, we’ll still be lying out here when the next rain comes. He’s holding up the whole advance. We don’t need to guarantee we get him. We just need to make it safer to move through that town.”

Harris stared at the map, jaw working, then looked up.

“All right,” he said. “You get what you need. But, Jensen?”

“Yes, sir?”

“If your rabbit tricks get anyone killed for nothing, I’m going to be very unhappy with you.”

Tom nodded, throat tight. “Yes, sir.”

He didn’t add: I’ll be very unhappy with me, too.

The smoke grenades arced out in a gentle pattern, plopping into the grass between their positions and the ridge.

Within seconds, thin gray plumes began to curl upward, carried by the light breeze into a low, shifting curtain.

It wasn’t a wall. Tom had insisted on that. Too much smoke might make the sniper go completely quiet, which was almost worse. Instead, it was like a veil, moving, changing, obscuring parts of the view but never all of it at once.

Back in his brush nest, fingers on the wires again, Tom waited.

“We ready up there?” he whispered into the field phone handset, pressed against his ear.

“Ready as we’ll ever be,” came the soft reply from the forward observers on a parallel rise. “We’ve got eyes on the notch. We’ll watch for any movement.”

Tom nodded, though they couldn’t see him.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s go teach a fox to chase a rabbit.”

He began the sequence.

Helmet one—up, down.

Helmet two—up, down.

Helmet three—up, down.

Then a rattle in tin number one.

He waited.

No shot.

The smoke wandered, thickening in some places, thinning in others. A gust opened a temporary window in the curtain, then closed it again.

He repeated the pattern, this time slightly altered—helmet three first, then one, then two. The rattles moved as well.

He imagined the sniper on the ridge, peering through his scope, watching shapes flicker in and out of partial cover.

“He’s thinking,” Tom said softly.

“Let’s hope he’s not thinking, ‘I’m going to shoot the kid with the wires,’” Cole replied under his breath.

On the third repetition, the sniper answered.

Crack.

The bullet hit the helmet by the gate dead center, plastic exploding in a dull puff. The stick snapped, the helmet flipped backward into the ditch.

Tom flinched but kept his fingers tight on the wires.

“Gate decoy’s down,” Cole reported quietly to Harris over the phone. “He nailed it.”

“Did you see any movement up there?” Harris’s voice crackled back.

The observers on the parallel rise answered.

“Negative,” one said. “Still in that notch. Didn’t see him move.”

Tom exhaled. “He’s too comfortable,” he muttered. “We’ve got to make him uncomfortable.”

“How do you make a man like that uncomfortable?” Cole asked.

Tom stared at the smoke as it coiled and thinned.

“Give him too many choices,” he said.

He altered the pattern again, this time making the helmets show in ways that didn’t match nervous men. Quick pops, slower ones, a helmet staying up just a hair too long as if daring him. The rattle of tins came in unlikely places, the timing off.

He wanted to annoy the sniper. Make him feel like someone down there was trying to be clever.

Snipers, Tom had read in some old book back at school, needed patience. They also needed control. They liked their prey predictable.

He tugged the wire on helmet two, held it up, counted.

One. Two. Thr—

Crack.

The helmet jumped as the bullet drilled it. It spun off the stick and landed at an angle.

“Two down,” Cole reported. “He’s good.”

“No kidding,” Tom murmured.

The observers’ voice came again, slightly more excited.

“Small movement in the notch,” he said. “Like he’s shifting his shoulder. Can’t see his face. But he’s reacting.”

“Good,” Tom said. “Let’s keep poking.”

He worked the last helmet for another few minutes, changing the rhythm, the pauses. He rattled tins sometimes without any helmet movement, sometimes all three together, sometimes none at all.

The sniper took longer this time.

When the shot came, it came slightly off.

The bullet grazed the top of the helmet, shaving a groove instead of punching through.

“Wind?” Cole asked.

“Or he’s adjusting too fast,” Tom said. “Trying to time weird patterns.”

The observer’s voice cut in, sharper now.

“Notch is empty,” he said.

Tom froze. “Empty?”

“Can’t see him,” the observer repeated. “He pulled back. We missed the actual moment, but he’s not in that spot anymore.”

Cole swore softly. “So we poked him hard enough to move,” he said. “Now we’ve got a ghost somewhere else.”

Tom’s mind raced.

“He’ll relocate to a spot that gives him a better view around the smoke,” he said. “Somewhere a little higher, maybe a little to one side. He’ll want a fresh angle on the road.”

“So where’s that?” Cole asked.

Tom thought of the ridge when he’d scanned it earlier. The notch had been slightly below a taller boulder, with a line of scrub to its right. To the left, a smaller outcrop overlooked the church steeple.

“If he goes right,” Tom said, “he gets a clearer shot at the orchard. If he goes left, he gets a cleaner shot at the lane and the cemetery.”

“Which one would you pick?” Cole asked.

“Right,” Tom said. “Better escape route behind the scrub.”

Cole nodded. “Then bet left.”

Tom blinked. “What?”

“Right feels safe to you,” Cole said. “It’ll feel safe to him. Which means we’re expecting him there, which means if he’s really as good as they say, he’ll know that. He’ll go where we least want him.”

Tom stared at the ridge again. The left outcrop was more exposed. Better view, worse cover. A bold shooter’s choice.

“Okay,” Tom said slowly. “Then we watch left.”

He raised the mirror again, angling it toward the left outcrop, the steeple, the sky.

Nothing.

“Maybe he’s farther back,” Tom said. “Or maybe he went right after all.”

Cole nodded toward the village.

“Only one way to know,” he said. “We give him something to shoot at, then see where the flash comes from.”

Tom’s stomach knotted.

“I’m running out of helmets,” he said.

Cole’s face softened for a moment.

“We’ll use something else,” he said. “Rifle over a wall, nothing underneath. I’ll have a man do it from inside a house, so he’s not exposed when the shot comes.”

Tom nodded, relieved.

“Meanwhile,” Cole added, “you get ready.”

“Ready for what?” Tom asked, though he already suspected.

“To go be a rabbit inside fox country,” Cole said.

The shot that decided it came ten minutes later.

A rifle barrel slid up gently over the corner of a low stone wall near the cemetery, wiggled slightly as if searching for a target, then steadied.

Tom watched through his own binoculars, breath shallow.

Crack.

The rifle jerked, splinters of stone jumped, and the barrel dropped.

Tom’s eyes flashed to the ridge.

“Left!” the observer shouted. “Flash on the left outcrop. Confirmed. He shifted there. I’ve got him. He’s hugging the rock, tucked behind a little hump, but that’s the spot.”

“Range?” Cole snapped.

The observer rattled off a number and bearing.

Cole looked at Tom.

“This is your part,” he said.

Tom licked dry lips. “My part?”

“You said you wanted to make rabbit tricks into fox traps,” Cole said. “We’ve found the burrow. Now we’ve got to stick something in it.”

Tom stared at the ridge.

“I’m not a marksman,” he said. “You’ve got better shots.”

“We do,” Cole agreed. “But this isn’t just about hitting a rock. It’s about knowing how he thinks. You’ve been living in his head for the last hour. You see the angles. You guess better where he’ll stick his eye out.”

Tom almost laughed. “My professors never warned me about that part of studying.”

Cole put a hand on his shoulder.

“Look,” he said. “You’re not going up there alone. We’ll send a small team along the side ravine, under cover. You’ll be with Corporal Davis. He’s one of our best with a rifle. But he doesn’t know this guy. You do. You call the shots. Davis pulls the trigger.”

Tom’s pulse thumped in his throat.

“Why not just… call in a couple of rounds right on that rock?” he asked weakly.

“Because that rock is within spitting distance of the back of the village,” Cole said. “We drop shells there, we risk hitting cellars full of people. Harris isn’t going to wear that.”

Tom knew he was right. There were already enough broken houses here.

“Besides,” Cole added, “this way, we learn something. About him. About you. About whether rabbit tricks can work twice.”

Tom let out a long breath.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay. Let’s go.”

The ravine that cut through the ridge’s flank was narrow, steep, and full of reasons to twist an ankle.

Tom climbed anyway, breath coming harder than he liked, boots slipping occasionally on loose stones. Corporal Davis moved ahead of him, rifle slung across his back, body low and controlled.

Davis was older than Tom by a handful of years, eyes lined with a quiet patience. He’d been a hunter back home, too—not rabbits, but deer in the hills of Pennsylvania.

“You sure about this, kid?” he murmured when they paused behind a jut of rock to catch their breath.

“Not even a little,” Tom replied.

Davis smiled faintly. “Good. Means you’re thinking.”

They reached a point where the ravine narrowed to a crack then resolved into a gentler slope near the crest. Davis slowed even more, checking each step, scanning ahead.

Tom dropped to a crouch, peeking over a clump of brush.

From here, he could see the left outcrop from an angle slightly behind and to the side. The rock bulged out like a frozen wave, with a depression in its front where someone could nestle, half-hidden. Behind it, a low mound of earth and scrub rose, forming a rough backdrop.

“He’s there,” Tom whispered. “Has to be. That’s the angle he used.”

Davis unslung his rifle, checking the sights.

“Okay,” he said. “You tell me where to aim. I’ll do the rest.”

Tom’s mouth was dry.

“He’ll expect someone to come for him eventually,” he said. “But maybe not from here. He’s watching the village, not his own flank.”

“And if he is watching us?” Davis asked.

“Then we’re in trouble,” Tom said honestly. “But we move like rabbits, remember? Short bursts, wrong rhythm.”

Davis nodded, adjusting his body in the shallow cover.

“Show me,” he said.

They moved, not in a straight line but in zigzags, using every scrap of rock and scrub. A few feet, then down. A pause, then a different angle. Sometimes they froze when instinct screamed move, trusting Tom’s sense that staying still at the wrong time might look right from above.

They got within thirty yards of the outcrop.

Tom’s heart pounded so loud he was sure the sniper could hear it.

“Here,” Davis whispered, sliding behind a low rock. “I can get a shot from here without exposing much. Question is, where do you want it?”

Tom studied the outcrop.

“He’ll be lying prone,” Tom said softly. “Rifle resting on the front edge. His body tucked back. There’s a little dip in the center—that’s where the rifle will be.”

“Shoot the dip?” Davis asked.

Tom hesitated.

“If we hit the rock right at the lip,” he said, “stone fragments might do more than the bullet. But…” He swallowed. “He’s been shooting at helmets all day. Small targets. If I were him, I’d use a slightly off-center angle to avoid a groove forming right in the middle of my cover.”

Davis raised an eyebrow. “So which side?”

Tom closed his eyes for half a second, imagining himself in that notch, feeling the weight of the rifle, the tug of the scope, the line of sight.

“Left,” he said. “He’d favor the left side. More cover from the smoke. Better angle on the lane.”

Davis nodded once.

“Left it is,” he said.

He settled the rifle, slow and deliberate, cheek against the stock. His breath steadied. The barrel hardly moved.

“On your call,” he murmured.

Tom looked one more time.

“Half an inch inside the left edge of that dip,” he whispered. “Aim like you’re trying to knock his scope off.”

Davis exhaled.

The shot, when it came, was oddly soft compared to the sniper’s sharp cracks. It was closer, more intimate.

The bullet hit the rock with a sound like someone slamming a hammer into a slate.

Stone chips flew, a small puff of dust rising.

For a heartbeat, nothing happened.

Then, from the notch, a figure jerked.

Tom saw only a flash—a gloved hand flailing, a rifle tipping, a sudden, involuntary movement that told him the impact had been felt.

The sniper tried to roll, to pull back, but his body moved wrong. Not like a man choosing to move, but like a body reacting.

Davis worked the bolt, fired again, this time slightly higher.

The second shot hit something that wasn’t rock.

The sniper slumped.

Silence washed over the ridge, thick and almost disorienting.

Tom realized he’d been holding his breath so long his chest hurt. He let it out in a shaky rush.

“Did we…?” he asked.

Davis’s face was unreadable for a moment, then softened.

“We did,” he said quietly. “Or at least, he’s not shooting anyone else today.”

They waited a full minute, watching for any twitch, any hint of motion. There was none.

“Stay put,” Davis said. “I’ll go check.”

Tom grabbed his arm. “Don’t,” he said. “If he’s somehow—”

“I’ll keep low,” Davis said. “But we’ve got to be sure. Men are going to move through that village. They’re trusting us.”

Tom’s hand loosened.

Davis moved forward, a whisper of cloth and the faint crunch of grit under his knees.

He approached from the side, staying below the line of the outcrop until the last second. Then he popped up just high enough to see over, rifle ready.

He lowered it almost immediately.

“It’s him,” Davis called back softly. “He’s done.”

Tom crawled up, every instinct still cautious.

The sniper lay half-twisted in his little stone nest, his rifle knocked askew. His face was pale, almost oddly peaceful, lines around his eyes suggesting age and strain. One lens of his scope was shattered, a starburst of glass. A neat, dark mark marred the edge of his head, just above the ear.

Tom looked at him a long moment.

“It’s him,” Davis repeated. “You can see why he was hard to find. He built this spot just right.”

Tom noticed the care in the setup: the way the rock lip had been chipped deliberately to create a firing slit, the bits of grass and dirt arranged to break up the outline of his body, the small pad under his elbows to steady his rifle.

“Professional,” Davis murmured. “No doubt about it.”

Tom felt no urge to pump his fist or cheer. Just a deep, exhausted relief.

“He was very good at what he did,” he said quietly. “Too good.”

Davis gave him a long, searching look.

“You okay, kid?” he asked.

Tom nodded slowly. “Ask me in a week,” he said. “Right now, I’m just glad we don’t have to crawl under his crosshairs anymore.”

They carefully removed the rifle, slid it out of the nest. Tom picked up the scope, turning it in his hands. The glass glinted dully, cracked and lifeless.

“This,” Tom said, “is what kept us pinned all morning.”

“And your rabbit tricks are what unpinned us,” Davis said.

Tom shook his head. “Not just mine,” he said. “Yours, too. And the guys with the helmets. And whoever thought to pack smoke grenades. And Cole, for listening to a scared student.”

Davis chuckled. “That’s the thing about rabbit tricks,” he said. “They work best in groups. Real rabbits have warrens full of them.”

When they came back down the ridge, the mood in the company was different.

Word had already spread: The sniper was down. The invisible hunter up on the rocks had stopped firing.

Captain Harris met them near the stone wall, eyes sharp.

“Well?” he asked.

Davis simply nodded.

Harris let out a breath Tom hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

“All right,” he said, voice low. “Get some water in you. We step off in ten. We’ve lost enough time to that one rifle.”

As Davis drifted away to rejoin his squad, Cole walked up and clapped Tom on the shoulder.

“Nice work, Rabbit,” he said.

Tom shrugged, uncomfortable. “We did what we had to do,” he said.

Cole’s gaze softened.

“That’s all any of us are doing,” he said. “But you… you did more. You saw the angles. You treated him like a problem to solve, not a ghost we had to fear forever.”

Tom managed a faint smile. “Problem-solving,” he said. “That’s what they teach us in engineering school. They didn’t say anything about hands shaking while you do it.”

“They will now,” Cole said. “You know they’re going to talk about this, right? Back at headquarters. ‘Student with rabbit tricks takes out famous sniper.’”

Tom winced. “Can we not call him ‘famous’?” he asked. “Feels weird.”

“Noted,” Cole said. “We’ll call him something else. Like ‘the man who underestimated a student from Ohio.’”

Tom looked back at the ridge, now just another lump of earth and stone.

“You think he really had four hundred confirmed?” he asked.

Cole shrugged. “That’s what intel said. Maybe it was fewer. Maybe more. Doesn’t matter much now.”

He studied Tom.

“What matters,” Cole said, “is that when everyone else froze, you looked for patterns. You remembered how rabbits move. You turned tricks for staying alive into a way to protect other people. That… that’s the kind of thing that gets remembered.”

Tom shook his head.

“If anyone remembers anything,” he said, “I’d like it to be that we figured out a way to get through that village without calling in big shells on those houses.”

Cole smiled crookedly.

“Deal,” he said. “We’ll leave the statistics to the historians.”

They moved through the village in a cautious wave.

Without the threat of a hidden sharpshooter, the streets felt different. Still dangerous—war didn’t disappear with one man—but less haunted.

Men moved from doorway to doorway, clearing rooms, checking cellars. A few civilians emerged, blinking in the light, faces wary but hopeful.

Tom walked with his squad, rifle held at low ready. His eyes scanned roofs, windows, alleys—not for a specific ghost on a ridge, but for anything that looked wrong.

“Still thinking in rabbit tricks?” Cole asked quietly as they passed the church.

“Always,” Tom said. “Once you start, you can’t stop. Every corner looks like a fox waiting to pounce.”

Cole nudged him. “That might be useful,” he said. “Foxes don’t like rabbits that see them coming.”

Near the square, they passed a house with broken shutters. An old woman stood in the doorway, clutching a shawl around her shoulders. She looked at the soldiers’ uniforms, then beyond them at the ridge.

She said something in French Tom didn’t understand, pointing upward.

“She’s asking if it’s safe now,” one of the French-speaking men translated. “Up there.”

Tom hesitated, then nodded.

“Oui,” he said, one of the few words he knew. “Safe.”

The woman’s shoulders sagged with relief.

She said something else, softer, voice trembling slightly.

“What did she say?” Tom asked.

The translator listened, then smiled, sad and wry.

“She said, ‘Perhaps now the sky will stop watching us all the time.’”

Tom looked up at the ridge, imagined the sniper’s scope scanning the houses, the lanes, the church. Watching them all the time.

“I hope so,” he said quietly.

Weeks later, in a quiet moment at the edge of another town, Cole found Tom sitting on an overturned crate, notebook open on his knees.

“You starting a romance novel?” Cole asked, dropping onto the crate beside him.

Tom smiled faintly. “Just… writing some things down,” he said. “Before they get fuzzy.”

Cole glanced at the page.

At the top, Tom had written:

RABBIT TRICKS – WORKS, BUT NOT MAGIC

Below that, a list:

– Never move in a straight line when someone is watching you with a rifle.

– Noise where you are not is as valuable as silence where you are.

– People with big numbers next to their names (kills, medals, titles) are still just people. They follow patterns.

– Mirrors see more than eyes, if you think about angles.

– Smoke doesn’t just hide you. It also forces others to make choices.

– Don’t hunt alone. Rabbits survive in groups.

Cole read silently, then tapped the last line.

“Not bad,” he said. “You going to send that back to your professors?”

Tom snorted. “I don’t think it fits in any of my old textbooks,” he said.

“Maybe it should,” Cole replied. “Engineering’s not just bridges and engines. Sometimes it’s about figuring out how to solve a problem no one wrote down yet.”

Tom closed the notebook.

“You think I’ll ever go back?” he asked quietly. “To school, I mean.”

Cole looked at him for a long moment.

“I think,” he said slowly, “that when this is over, there are going to be a lot of problems that need solving. Bridges to rebuild. Houses. Lives. People who can think in rabbit tricks and steel beams at the same time? They’ll be useful.”

Tom nodded, staring at his hands.

“And if I do go back,” he said, “and someone asks what I did out here… what should I say?”

Cole shrugged.

“Tell them you saw how people act when they’re scared,” he said. “Tell them you learned that sometimes the best way to survive is to move in ways the danger doesn’t expect. And if they push you for something colorful…”

He grinned.

“You can tell them,” Cole said, “that once upon a time, a nervous student with a pocket mirror and a bag of rabbit tricks outwitted a German sniper with four hundred confirmed kills. And that, thanks to that, an entire company walked through a village that might’ve been a graveyard.”

Tom smiled, a little embarrassed, a little proud.

“Sounds like a tall tale,” he said.

“Let them think that,” Cole replied. “The enemy thought the same thing about you. That’s why you’re still here.”

Tom looked out across the fields, where the ridge in that French village was just a memory now, distant and small.

He thought of the sniper’s careful nest. Of helmets on sticks. Of smoke drifting and mirrors flashing. Of the moment when the man who had ended so many lives had finally, for once, run out of angles.

He didn’t feel triumph.

He felt… the weight of it. The knowledge that, in some ledger somewhere, someone had written “400” next to that sniper’s name—and then left the next line blank because the student with rabbit tricks had made it impossible to fill in.

He hoped no one ever had to do that particular kind of math again.

“Hey, Rabbit,” Cole said, standing. “We’re loading up in five. You coming, or you going to sit there and think us all to victory?”

Tom stood, tucking the notebook into his jacket.

“Thinking’s part of the job,” he said. “But yeah. I’m coming.”

They walked back toward the trucks, boots scuffing dust, gear clinking softly.

Above them, the sky was just sky again.

No scope watching.

No invisible eye counting.

Just clouds, sunlight, and, somewhere far away, a memory of a ridge where a student had proven that sometimes, brains and a handful of tricks could bend even the deadliest pattern.

THE END

News

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

The Hour That Shook Two Nations

After watching a mysterious 60-minute demonstration that left him speechless, Churchill traveled to America—where a single unexpected statement he delivered…

The General Who Woke in the Wrong World

Rescued by American doctors after a near-fatal collapse, a German general awakens in an unexpected place—only to witness secrets, alliances,…

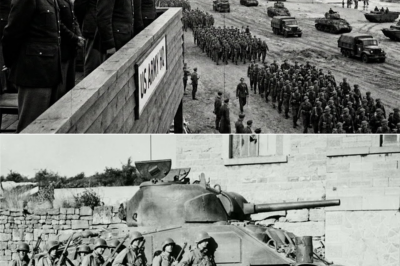

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning—but instead uncovered a web of astonishing D-Day preparations so elaborate, bold,…

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline. The Fake Takedown Video That Fooled Viewers, Enraged Comment

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline….

End of content

No more pages to load