Our Small-Town Funeral Stopped Cold When My Niece Shouted That the Woman in the Casket Was Breathing, and the Battle That Followed Between Faith, Science, and Denial Changed What Our Family Believed About Life and Death

The first time my daughter said she saw something nobody else did, she was three.

We were in the grocery store checkout line, and she tugged on my sleeve with her sticky little hand.

“Mom,” she whispered, big brown eyes serious, “the lady behind us is sad.”

I glanced over my shoulder.

The woman behind us looked perfectly normal: jeans, T-shirt, expression blank as she scrolled through her phone. I turned back to our cart, half-listening for the beep of scanned items.

“She doesn’t look sad,” I murmured.

Sofía frowned.

“Her heart looks sad,” she insisted.

Three weeks later, we ran into the same woman at the pharmacy. Her head was wrapped in a scarf. Her eyelashes were gone. She waved when she saw us.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m starting chemo this week. Long road ahead.”

I remembered my daughter’s words, and a chill slid over my skin.

After that, I stopped dismissing Sofía’s strange little comments.

I didn’t think much of that moment in the grocery store when I drove to the funeral home three years later. My mind was crammed with other things: maps, directions, the list of relatives I needed to text, the cinnamon rolls my aunt had insisted we bring for the post-service coffee.

My grandmother’s death had come fast.

A stroke on a Tuesday afternoon.

An ambulance, a hospital, the cold blue light of machines.

By Wednesday morning, she was gone.

“Mass on Saturday,” my mother had said over the phone, voice brittle. “Viewing first. At Castillo’s. Ten a.m.”

I’d said I’d be there.

Of course I would.

Abuela Rosa had lived with us for most of my childhood. She’d been the one making tortillas in the kitchen when my mom worked double shifts at the nursing home. She’d been the one who’d taught me the proper way to sew on a button, how to tell when avocados were ripe, which herbs to plant in coffee cans on the fire escape.

“When I die,” she used to say, waving a wooden spoon, “I don’t want drama. No wailing, no fainting. Just a few flowers, some music, and people telling good stories. Then everybody goes home and eats.”

She said it so often it had become a joke.

“Rosa,” my grandfather would grumble, “stop talking like that. You’re going to outlive us all.”

She didn’t.

On Saturday morning, the sky was a clear, painfully bright blue, the kind that felt almost rude.

“Why is the sun shining if everybody’s sad?” Sofía asked from the back seat, kicking her heels against the booster.

“Because the world doesn’t stop, mija,” I said, my fingers tight on the steering wheel. “Even when we want it to.”

She considered that for a moment.

“It should,” she said finally. “Just for a little bit.”

I couldn’t argue with that.

Castillo & Sons Funeral Home sat on the corner of Willow and Third, a squat beige building with a parking lot that always seemed to have too many cars in it. The sign out front had a dove painted on it and a slogan in curly letters: “Celebrating Life With Love.”

I parked between my cousin Mateo’s pickup and a minivan plastered with honor roll bumper stickers.

“Okay,” I said, unbuckling my seat belt. “Ground rules.”

Sofía sighed dramatically.

“I remember,” she said. “Be quiet. Don’t run. Use inside voice. No eating mints off the tables without asking first.”

“Exactly,” I said. “And remember, Abuela is sleeping, kind of. We’re saying goodbye to her body, but the part of her that loved us is with God now.”

She chewed on her lip.

“Does God make tortillas?” she asked.

The question punched a laugh out of me when I’d thought there weren’t any left.

“I hope so,” I said. “Abuela would insist.”

Inside, the air was thick with the smell of lilies and furniture polish. The carpet was that institutional burgundy that shows every speck of lint. Soft instrumental music floated from hidden speakers, the kind designed to sound like generic solace.

The viewing room was already half full.

My mother stood near the front in a black dress, her hair pulled back into a bun so tight it looked like it hurt. She had a tissue clutched in one hand, crumpled into a damp ball.

“Elena,” she said when she saw me, the corners of her eyes crinkling. “You made it.”

“Of course,” I said, leaning in to kiss her cheek. “How are you?”

“How do you think?” she said, and the brittle humor in her voice told me she was hanging on by a thread. “Your grandmother was stubborn. I thought she’d be bossing me around from a wheelchair at ninety-five.”

“She probably still will,” I said. “Just from the other side.”

My mother snorted.

“Don’t give her ideas,” she said.

Sofía slipped her small hand into my mom’s.

“Hi, Nana,” she said. “Are you sad?”

My mother’s face softened.

“A little,” she said. “But I’m happy too. Your Abuela isn’t in pain anymore.”

Sofía nodded solemnly.

“Can I see her?” she asked.

My stomach tightened.

“Yes,” I said. “But remember what we talked about.”

She nodded.

We walked toward the front of the room.

The casket sat on a raised platform, open, lined with white satin. It looked expensive in a way my grandmother would have hated.

“They charge extra for the nice pillows,” she would’ve said. “Waste of money. You think I’m going to complain?”

A spray of white roses and baby’s breath spilled across the lid, trailing ribbons with “Mamá” and “Abuelita” written in gold script.

I swallowed.

Took a breath.

Then forced myself to look.

People always say the dead look “peaceful” at funerals.

My grandmother didn’t.

She looked… wrong.

Too still.

Her skin had a waxy tint, the color just slightly off.

Her hair, usually pulled back in a bun, lay arranged around her shoulders in soft waves I’d never seen in life.

Her hands were folded over a rosary on her chest, fingers laced just so.

It was her, but not.

My throat tightened.

“Hi, Abuela,” I whispered. “You’d hate your hair.”

Sofía stepped forward.

She was just tall enough that her eyes cleared the edge of the casket.

For a second, she just stared.

Her brows pulled together.

“Mom,” she whispered.

“Yeah, baby?” I asked.

“She doesn’t look like herself,” she said. “She looks… sleepy. But not really.”

I swallowed.

“Sometimes the people who prepare the body at the funeral home do makeup and stuff,” I said quietly. “They’re trying to make her look nice. To help us remember her. But it’s okay if it feels weird.”

She nodded slowly.

We stood there for another minute, silent, each lost in our own thoughts.

Behind us, people murmured.

Aunts hugged cousins.

Uncles patted each other’s backs.

The smell of cologne, powder, and floral arrangements blended into something almost suffocating.

“Okay,” I said finally, my voice rough. “Let’s go sit down. We’ll come up again later if you want to.”

We turned away.

Halfway back to the pew, my cousin Mateo grabbed my arm.

“Elena,” he whispered. “Did you hear? Tía Marisol is already arguing with your mom about the will.”

I sighed.

“Of course she is,” I said. “It wouldn’t be a family gathering without Marisol making it about money.”

“Careful,” he said. “She’s on the warpath. Something about the house, the jewelry, the—”

He cut off as my Aunt Marisol swept past, her perfume strong enough to choke.

“Elena,” she said, air-kissing my cheek. “You look so thin. Are you eating?”

“Hi, Tía,” I said. “You look… very dressed up.”

She preened, smoothing an invisible wrinkle from her black dress.

“Well, we must honor your grandmother with dignity,” she said. “Even if some people do not understand what that means.”

Her eyes darted toward my mother, who was deep in conversation with the priest.

I clenched my jaw.

“Not today, Tía,” I said quietly. “Please.”

She sniffed.

“We will talk later,” she said. “There are many things to discuss.”

“I can’t wait,” I murmured, rolling my eyes as she flounced away.

We found seats halfway up the middle row.

Sofía sat between me and my sister Ana, swinging her legs and examining the hymnals in the pew pocket.

“When do we sing?” she whispered.

“Soon,” Ana said, ruffling her hair. “You can sing extra loud. Abuela loved your voice.”

Sofía smiled.

The priest cleared his throat at the front.

People began to settle, the murmur of conversation dying down.

I shifted in my seat, smoothing my skirt, my eyes drifting back to the casket at the front of the room.

My grandmother lay there, still and strange.

I felt a wave of anger rise in my chest.

At death.

At hospitals.

At God.

At my parents for their smug theology.

At myself for not having visited her more often.

The priest began speaking.

“In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit…”

I tried to listen.

Really, I did.

But half my attention was on Sofía, making sure she was okay.

She swung her legs.

Flipped through the hymnbook.

Whispered questions to Ana.

At one point, she turned and watched my mother, head cocked.

“She looks like she’s going to explode,” she whispered, not as quietly as she thought.

Ana snorted.

“That’s just her face,” she whispered back.

“Shh,” I hissed, trying not to laugh.

The priest read from Psalms.

A distant aunt sniffled loudly into a lace handkerchief.

My phone buzzed in my purse.

I ignored it.

The last thing I needed was my parents texting more Bible verses from three states away while we sat at a funeral they hadn’t bothered to attend.

They’d claimed “health reasons.”

We all knew better.

Halfway through the priest’s homily, my thoughts had wandered so far I almost didn’t notice Sofía slide off the pew.

I looked down.

Her seat was empty.

My heart jumped.

I scanned the aisle.

She was halfway to the front, her small figure threading through the rows of black-clad adults.

“Sofía,” I hissed under my breath. “Get back here!”

She didn’t look back.

She walked straight toward the casket.

My stomach dropped.

Ana grabbed my arm.

“Let her,” she whispered. “She’s okay.”

“She’s going to trip,” I whispered back. “She’s—”

She stopped at the edge of the platform.

For a second, she just stood there, staring down at my grandmother’s face.

Like before.

Then she did something that snapped every head in the room toward her.

She pointed at the casket with her small hand.

Her voice, clear and high, cut through the priest’s gentle monotone.

“She’s alive,” she said.

A ripple went through the room.

Someone laughed nervously.

The priest stalled.

“Sweetheart,” he said gently. “We know your Abuela is alive in heaven, but—”

“No,” Sofía said, stamping her foot the way she did when she was frustrated with math homework.

“She’s alive. Right there. In there.”

She jabbed her finger toward the casket.

The room froze.

“Sofía,” I said sharply, standing. “That’s enough. Come back here.”

She turned, eyes wide and earnest.

“Mom,” she said. “She’s breathing.”

My mouth went dry.

“What?” I whispered.

“She’s breathing,” Sofía repeated urgently. “I saw her chest move. And her fingers. Look.”

She turned back to the casket.

The funeral director, Mr. Castillo, shifted uncomfortably near the door.

He cleared his throat.

“Sometimes,” he began, his voice calm and practiced, “after someone passes, there can be… reflexive movements. It’s completely normal. It doesn’t mean—”

“She’s alive,” Sofía insisted, louder now. “Why is nobody listening?”

The priest shot me a sympathetic look.

My aunt Marisol tutted under her breath.

“Take her away,” she muttered. “She’s upset. Children say things like that. They don’t understand.”

My cheeks burned.

I wanted to scoop Sofía up, apologize to the room, sit down, and pretend it hadn’t happened.

That’s what a “good” daughter would do.

A “good” mother.

A “good” church member.

Keep the peace.

Smoothe the edges.

Ignore the uncomfortable.

But something about the way Sofía stood there, small and stubborn, finger pointed, made my chest ache.

She looked so much like my grandmother in that moment it hurt.

The set of her jaw.

The tilt of her chin.

The fire in her eyes when she thought she was right.

“Mom,” she pleaded, turning back to me. “Please. Just look.”

The room waited.

Everyone looking at me now.

The priest, with his calm sorrow.

My mother, with her red-rimmed eyes and tight mouth.

My aunt, with her impatient frown.

The funeral director, with his rehearsed sympathy.

My uncle, with his hand on his wife’s shoulder.

Mateo, his eyebrows raised.

Ana, her gaze steady.

For thirty-two years, I’d been the one who tried to make everyone else comfortable.

Biting my tongue.

Smoothing over fights.

Laughing off slights.

Playing the role.

But right then, something in me remembered the grocery store.

The woman with the sad heart.

The scarf.

The chemo.

My daughter’s quiet certainty.

I took a breath.

“Okay,” I said.

My voice sounded too loud in the sudden quiet.

“Okay, mija. Show me.”

Gasps.

Whispers.

“Elena, don’t encourage this,” my mother hissed.

“Rosa wouldn’t want—” my aunt started.

“I’m not doing this for them,” I said, more sharply than I’d intended.

I walked up the aisle.

Each step felt like wading through mud.

My legs were heavy.

My heart hammered.

When I reached Sofía’s side, she grabbed my hand.

Her fingers were cold.

“She moved,” she whispered. “I saw it. Right here.”

She pointed to my grandmother’s folded hands.

“Okay,” I murmured. “Let’s see.”

I leaned over the casket.

Up close, my grandmother’s face still looked too still.

But now that I was looking for it—not just glancing, not just forcing myself to take in the general shape but really looking—I noticed something.

A tiny glint of moisture at the corner of her mouth.

Not much.

Just a little shine.

“She’s dead, Elena,” my mother said from behind me, her voice shaking more with anger than grief now. “Don’t do this to yourself. Don’t let a child’s imagination—”

“Shh,” I said softly.

I held my breath.

Stared.

At first, nothing.

Then—

Her finger twitched.

It was small.

Barely noticeable.

A tiny flex of the knuckle against the rosary bead.

If I hadn’t been inches away, I would’ve missed it.

I sucked in a sharp breath.

“What?” my mother demanded. “What is it?”

I swallowed.

Leaned closer.

“Abuela?” I whispered.

Nothing.

I pressed my fingertips lightly to the side of her neck, where the pulse point was.

Cold.

Nothing.

Maybe it was my imagination.

Maybe it was a reflex.

Maybe I was losing my mind.

“Mom,” Sofía said urgently, tugging at my sleeve. “Her chest. Watch her chest.”

I followed her gaze.

We watched.

The entire room watched.

For a long, unbearable moment, there was nothing.

Just the silence of a hundred people collectively holding their breath.

Then, slowly, her chest rose.

Barely.

Like a whisper of air.

It fell.

Rose again.

Fell.

“Jesus,” Mateo breathed.

Someone crossed themselves.

My aunt gasped.

“No,” my mother whispered. “No. That’s not—that’s—”

The funeral director stepped closer, his face paling.

“That’s not possible,” he muttered. “I pronounced her… we had the certificate…”

“Possible or not,” I said, my voice going high and strange, “she’s breathing.”

I pressed my fingers back to her neck.

Nothing.

Then, so faint I almost doubted it—

A flutter.

Weak.

Off-rhythm.

But there.

Like a bird beating its wings against the window of her skin.

“She has a pulse,” I said.

My voice shook.

“She has a pulse.”

Chaos erupted.

“Call 911!” someone shouted.

“Get a doctor!”

“Don’t touch her!”

“Is this a miracle?”

“Is this legal?”

“Quiet!” the priest barked, surprisingly loud.

He moved toward the casket, his stole swinging.

“We need to proceed with caution,” he said. “We don’t know what we’re dealing with here.”

“What we’re dealing with,” I snapped, “is my grandmother breathing on a table. I don’t care if it’s a miracle or a malfunction. Call an ambulance.”

The funeral director hesitated.

“But the paperwork,” he said weakly. “The body has already been—”

“Her name is Rosa,” I said, my voice so sharp it sliced through his words. “Not ‘the body.’ And if you don’t call 911 right now, I will.”

The room fell quiet.

My mother grabbed my arm.

“Elena,” she whispered, “what if you’re wrong? What if it’s just… you know, nerves. Gas. Something. You’re going to rip her out of peace. You’re going to—”

“What if I’m not?” I shot back. “What if she’s in there, hearing us, and we just stand here and do nothing?”

She flinched.

“Elena, be reasonable,” my aunt Marisol said, her voice rising. “The doctors said she was gone. You want to go against the hospital? Against the church? For what? So you can say you listened to your daughter?”

“Yes,” I said simply.

“She’s a child,” my aunt said, disgust dripping from the word. “She doesn’t understand the world. She—”

“She noticed something none of us did,” I said. “That counts for something.”

Behind us, murmurs.

People choosing sides.

My cousin Isabella stepped forward.

“Elena’s right,” she said. “We have to call. We can’t just… pretend we didn’t see that.”

My uncle Sergio shook his head.

“This is insane,” he muttered. “You’re going to get sued. The funeral home is going to get sued. The hospital…”

“Let them sue,” I snapped. “I’d rather be sued than sit here and watch my grandmother die a second time because we were too polite to make a scene.”

The priest raised his hands.

“Enough,” he said. “We are all under stress. Let us breathe.”

He looked at the funeral director.

“Mr. Castillo,” he said. “Please call emergency services. We must rule out all possibilities. If this is, as some believe, a… reflex, then we will know. If it is something else…” He glanced at the crucifix on the wall. “Then we will know that too.”

Mr. Castillo swallowed.

Nodded.

Scurried out of the room, his cellphone already at his ear.

The room hummed with low voices.

Fear.

Hope.

Anger.

My mother squeezed my arm.

“Do you realize what you’re doing?” she whispered. “If this is some kind of… resurrection… people will talk. The church will talk. The hospital will talk. Your aunt will never shut up. Your father will—”

“Maybe people should talk,” I said. “Maybe they should ask how a hospital declared her dead when she wasn’t.”

“This is God’s will,” she hissed. “You cannot interfere.”

“Maybe God’s will is that my daughter walked up here and pointed at the casket,” I shot back. “Maybe His will is that we notice. That we act. That we stop treating the signing of a paper like the end of the story.”

Her eyes flashed.

“You’ve been spending too much time with those new friends of yours,” she said bitterly. “You think you can just change the rules because you feel like it.”

“This has nothing to do with my friends,” I said. “This has to do with Abuela breathing.”

Sofía tugged my hand.

“Mom,” she whispered. “Is she going to wake up?”

I looked down at her.

Her eyes were huge.

Hopeful.

Terrified.

“I don’t know, mija,” I said honestly. “But we’re going to try to help her, okay? We’re going to give her every chance.”

She nodded.

“Okay,” she said. “I told you she was alive.”

A ghost of a smile tugged at my mouth.

“You did,” I said. “You did good, bug.”

“My heart told me,” she whispered.

I believed her.

Sirens wailed in the distance.

The sound grew louder.

Closer.

In minutes, two paramedics pushed through the doors, their bright uniforms a shocking splash of color in the sea of black clothing.

“What have we got?” one asked, professional and fast.

“Woman,” I said. “Seventy-nine. Declared dead at county hospital last night after stroke. We were at the viewing. My daughter noticed movement. I thought she was imagining it. Then I saw her chest rise. Felt a pulse. Weak, but there.”

The paramedic’s eyes widened.

“You felt a pulse?” he repeated.

“I know how to find one,” I said, a little sharper than intended. “I’m not crazy.”

He held up a hand.

“Not saying you are,” he said. “Just… not something we hear every day.”

He moved to the casket.

“Ma’am?” he said aloud, as if my grandmother might answer. “I’m going to check you out, okay?”

He placed fingers at her neck.

His partner watched the clock.

A beat.

Another.

I held my breath.

“Got something,” the paramedic said, eyes narrowing. “Slow. Thready. But it’s there.”

A low murmur went through the room.

My knees went weak.

I grabbed the edge of the casket.

The other paramedic pulled a small flashlight from his pocket and gently lifted one of my grandmother’s eyelids.

“Pupils reactive,” he said softly. “She’s not… all the way gone.”

My mother made a strangled sound.

“This can’t be happening,” she whispered.

“Oh, it’s happening,” my cousin Mateo muttered. “I got it on video.”

“Ay, Dios,” my aunt hissed. “Put that phone away!”

The paramedics went into efficient mode.

They called for a stretcher.

They consulted with Mr. Castillo about the paperwork.

There was a flurry of phone calls, hushed arguments, someone from the hospital on speakerphone saying, “That’s impossible,” and the paramedic saying, “Respectfully, ma’am, I’m telling you what I’m seeing.”

They lifted my grandmother carefully out of the casket.

She looked small.

So much smaller than she had in life, when she’d filled rooms with her laughter and her opinions and the smell of simmering beans.

They placed her on the stretcher.

Hooked up portable monitors.

My eyes fixed on the green line on the screen.

Tiny blips.

Not what you’d want in a healthy person.

But not flat, either.

Beep.

Beep.

Beep.

My chest tightened.

Sofía squeezed my hand so hard my fingers tingled.

“See?” she whispered. “I told you.”

“You did,” I whispered back, my voice cracking.

As they wheeled my grandmother out, the room split.

Half of my relatives followed, a knot of dark fabric and murmured Hail Marys.

The other half stayed, sitting in shocked silence, staring at the empty casket as if it might offer some explanation.

The priest stood at the front, hands clasped, his face pale.

“This has never happened in all my years,” he murmured.

Mr. Castillo ran a hand through his thinning hair.

“I don’t get paid enough for this,” he muttered.

My mother stood in the aisle, torn.

She looked at the door.

Then at the casket.

Then at me.

“This is wrong,” she whispered. “She was ready. She was at peace. We’re dragging her back. We’re… interfering.”

“Or we’re correcting a mistake,” I said. “A big one.”

“What if she comes back… wrong?” my aunt Marisol hissed. “What if she’s… not herself? What if she suffers? Then what? You going to take care of her? You going to pay for the hospital?”

“Yes,” I said, surprising myself.

“Whatever happens,” I said more firmly, “we’ll handle it. Together. Like family. That’s what we’re supposed to be.”

She snorted.

“Easy for you to say,” she muttered. “You live in the city. You come down once a month, bring your fancy coffee, and think you know everything.”

“Stop it,” my mother snapped.

We both turned.

She’d gone very still.

Her eyes, which had been wild and unfocused, seemed to sharpen.

“This is not the time,” she said. “My mother is being loaded into an ambulance, and you two are going to argue about who buys coffee? Enough.”

Her voice cracked like a whip.

We shut up.

She turned to me.

“You think this is God’s will?” she asked quietly. “That she… woke up?”

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “But I think ignoring it would be wrong.”

She nodded slowly.

Then, to my surprise, she reached for my hand.

Her fingers squeezed mine, hard.

“Then let’s go,” she said. “If she’s going to wake up, she should see familiar faces.”

We followed the stretcher out.

The sunlight outside was blinding after the dim interior of the funeral home.

The ambulance doors stood open, the paramedics sliding my grandmother inside.

Neighbors and small-town onlookers had gathered on the sidewalk, drawn by the sirens and the crowd.

“Is that Rosa?” someone whispered.

“What’s going on?”

“Didn’t they say she was dead?”

“Maybe it’s like that lady on the news who woke up in the morgue.”

We climbed into cars.

My mother rode in the front with my uncle.

I strapped Sofía into her booster seat, my hands shaking.

“Are we going back to the hospital where Abuela was?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “They’re going to check her again. See what’s going on.”

“Is she going to be okay?” she asked, her voice small.

“I don’t know,” I said, hating the words. “But we’re going to be there. That’s what matters.”

On the drive, my phone buzzed nonstop.

Group texts.

Cousins.

Friends.

People who’d left the funeral early and were now hearing secondhand that “Rosa came back to life.”

My father texted, finally.

Dad: Your mother told me some nonsense about your grandmother breathing at the funeral. What are you doing over there? Don’t make this into a circus.

I stared at the screen.

Laughed.

A short, sharp sound that carried no humor.

Me: We called an ambulance. She had a pulse.

Dad: Impossible.

Me: The paramedics disagreed.

There was a long pause.

Then:

Dad: We are praying.

I rolled my eyes.

Of course they were.

Praying from a safe distance.

I put the phone down.

Focused on the road.

At the hospital, everything moved fast.

Doctors.

Nurses.

Machines.

Tests.

They whisked my grandmother into a quiet room in the ICU.

They asked questions.

When had she been declared dead?

Who had pronounced her?

What had her vitals been before that?

My uncle fumbled through his notes.

The hospital scrambled to find the attending who’d filled out the death certificate.

He looked like he wanted to sink through the floor when he saw my grandmother on the monitor, her heart tracing weak blips across the screen.

“This is… exceedingly rare,” he said, stumbling over the words. “Sometimes… after resuscitation attempts, there can be a phenomenon where the heart… starts again later. We call it the Lazarus phenomenon. It’s… almost never seen. I’ve only read about it.”

“Lazarus, like in the Bible,” my mother muttered.

The doctor winced.

“Yes,” he said. “But I assure you, this is not… divine intervention. It’s… physiology. The body… well…” He trailed off, hearing himself.

He looked at me.

“At any rate,” he said, “she’s… technically alive. For now. But in a very unstable state. We need to be realistic. Her brain went without oxygen for an unknown period. If she wakes up… and I want to emphasize that’s a big if… we don’t know what her cognitive function will be.”

“So we just… wait?” I asked.

He nodded.

“For now,” he said. “We support her body and… see.”

Support her body.

See.

The language was so clinical it made me want to scream.

In the hallway outside, our family erupted into another argument.

“What did I tell you?” Aunt Marisol hissed. “She’s going to be a vegetable. We should have left her. Now we’re stuck in some… half state.”

“How can you say that?” Mateo snapped. “It’s Abuela, not an old car you can just junk.”

“She told me,” my aunt insisted, “that she didn’t want machines. She didn’t want tubes. She didn’t want to be kept alive if she couldn’t boss anyone around.”

“That’s not what this is,” I said. “We’re not hooking her up to some machine against her will. She started breathing. On her own. We’re just… seeing if she keeps doing it.”

“Enough with ‘seeing,’” my aunt said. “At some point, we have to accept reality.”

“What reality?” I snapped. “Because last time I checked, reality changed pretty dramatically when she started breathing in the casket.”

“Stop it,” my mother said, her voice shaking.

We turned.

She looked tired.

Older.

Fragile in a way I’d never seen before.

“We are not going to tear each other apart in this hallway,” she said. “My mother is in there. I don’t know if she’s alive or dying or some strange thing in between. But I am not going to stand here and listen to you talk about her like a… problem. If you want to argue, go outside.”

Her voice cracked.

Her eyes filled.

“Please,” she whispered. “I can’t. Not right now.”

Silence fell.

My aunt opened her mouth.

Closed it.

“We’ll… get coffee,” she muttered finally.

The group dispersed.

I watched my mother sag against the wall.

“Hey,” I said softly, stepping closer. “You okay?”

She laughed, a brittle sound.

“Of course I’m not okay,” she said. “My dead mother isn’t dead anymore and my family’s acting like they’re on a reality TV show. But other than that, I’m fine.”

I smiled.

Just a little.

She looked at me.

“You were right,” she said quietly.

The words shocked me more than my grandmother’s pulse.

“About what?” I asked.

“About… acting,” she said. “About not just… accepting what we’re told.”

She swallowed.

“I was so ready,” she whispered. “To believe the doctors. The priest. Even your father. ‘God’s will,’” she said, mocking his deep tone. “So ready to tell myself this was… the end. That it was my job to be sad and graceful and not make a fuss. And then your little Sofía walked up there and pointed and… refused to let everybody be comfortable.”

She looked at me.

“I’m glad you listened to her,” she said simply.

My throat tightened.

“I am too,” I said.

We sat in the ICU waiting room for hours.

People came and went.

Relatives fretted.

The priest came by and said prayers at the bedside, his words softer now, more tentative.

The doctor checked on my grandmother, adjusted her IV, frowned at the monitor.

Through it all, Sofía stayed by my side.

She colored in a little notebook a child life specialist had given her.

At one point, she looked up at me.

“Do you think Abuela heard me?” she asked.

“When?” I asked.

“When I said she was alive,” she said. “When everybody else was sitting down.”

I looked at the ICU doors.

At the tiny window through which I could see the edge of my grandmother’s bed.

“I hope so,” I said. “I hope she heard you yelling loud enough for both of us.”

Sofía nodded, satisfied.

Later that night, sometime between the beep of one machine and the whoosh of the automatic door, my grandmother squeezed my hand.

It was small.

Weak.

But unmistakable.

Her eyelids fluttered.

Her lips moved.

For a second, I thought I heard her murmur my name.

Then the line on the monitor hiccupped.

Beep.

Beep.

Beeeeeeep.

The alarm sounded.

Nurses rushed in.

We were ushered out.

By the time they let us back in, the doctor’s face said everything.

“I’m sorry,” he said softly. “Her heart stopped. We… we tried. This time… it’s… final.”

My mother closed her eyes.

Let out a long, shuddering breath.

“So she died… twice,” my aunt Marisol said, sounding dazed.

“It’s not… like that,” the doctor said. “It’s… complicated.”

“It’s complicated,” I repeated.

My grandmother lay still again.

The same stillness I’d seen at the funeral home.

But this time, there was no flutter.

No rise.

No twitch.

Just silence.

Except for the echo of my daughter’s voice in my head.

“She’s alive.”

Later, after the second funeral—smaller, quieter, because half the family didn’t have the emotional bandwidth for round two—we sat at my mother’s kitchen table.

The table where my grandmother had rolled tortillas, snapped green beans, taught me how to make arroz con leche.

Sofía sat between us, dunking a cookie into milk.

My mother sipped her coffee.

“I keep thinking,” she said slowly, “about what would’ve happened if we hadn’t listened.”

I stared at my mug.

“We never would have known,” I said quietly. “We would have buried her and gone home and… never realized she’d… come back, even for a little while.”

“Do you regret it?” she asked.

I thought about the hospital.

The argument.

The ambulance.

The brief squeeze of my grandmother’s hand.

The way she’d looked at me, just for a second, like she recognized me.

“No,” I said.

My mother nodded.

“Me either,” she said.

We sat in silence for a moment.

Then she reached across the table.

Put her hand over Sofía’s.

“You have a special heart,” she said softly. “You see things we don’t.”

Sofía shrugged bashfully.

“I just… felt it,” she said. “Like… like when the weather’s going to rain. You just know.”

My mother smiled, a little.

“We’re going to need you to tell us when we’re being silly,” she said. “When we’re… missing something important.”

Sofía grinned.

“I can do that,” she said.

My phone buzzed on the table.

A text from my dad.

Dad: Your mother tells me… everything went okay yesterday.

I snorted.

“Okay” was doing a lot of heavy lifting there.

Dad: It was a test from God. You passed.

I rolled my eyes.

Me: It was a second chance. She took it.

There was a pause.

Dad: We’ll come visit next month.

I thought about it.

About the argument in the hospital.

About hanging up.

About boundaries.

About the way my mother had started to question things she used to recite.

About the way my father still defaulted to “test” and “lesson.”

I took a breath.

Me: We’ll see.

I put the phone down.

Looked at my daughter.

At my mother.

At the empty chair where my grandmother used to sit.

“Abuela would’ve laughed,” my mother said suddenly, eyes wet and bright. “She would’ve said, ‘Leave it to me to be too stubborn to stay dead the first time.’”

We all laughed.

It hurt.

But it felt good too.

Like stretching a muscle that had gone stiff.

Later that night, after I’d tucked Sofía into bed and kissed her forehead, she looked up at me with sleepy eyes.

“Mom?” she whispered.

“Yeah, baby?” I said.

“Were you scared?” she asked. “At the funeral. When I yelled.”

I thought about the room.

The stares.

The priest.

The funeral director.

My mother’s hissed warnings.

My aunt’s glares.

“Yes,” I said, honest.

“I was very scared.”

“Why?” she asked, frowning.

“Because I didn’t know what would happen,” I said. “If I listened to you. If I didn’t. If I made everyone mad. If I was wrong.”

She considered that.

“But you listened anyway,” she said.

I smiled.

“I did,” I said.

“Why?” she pressed.

I brushed a strand of hair off her forehead.

“Because you’re my daughter,” I said. “And because… sometimes, the people everybody thinks are too small to matter are the ones who see what’s really going on.”

She smiled sleepily.

“Like David and Goliath,” she murmured.

“Yeah,” I said. “Like that.”

She yawned.

“I’m glad you listened,” she said. “Abuela got to… come back for a little bit. To say bye.”

“Me too,” I whispered.

I turned off the light.

Closed the door almost all the way.

In bed that night, staring at the cracks in my ceiling, I thought about all the moments in my life when I’d chosen silence.

On rooftops.

In hospital rooms.

On phone calls with my parents.

In pews.

In meetings.

At tables.

Every time, I’d told myself I was keeping the peace.

Being “good.”

Avoiding drama.

But my daughter, with her too-big eyes and her too-soft heart, had stood up in a room full of grown-ups and pointed at something everyone else had agreed was unchangeable.

“She’s alive.”

And in the seconds that followed, I’d had a choice.

Believe her.

Or believe everyone else.

Trust the paperwork.

Or trust the pulse under my fingers.

I’d chosen her.

I’d chosen to make a scene.

To risk embarrassment.

To risk being wrong.

To risk being called crazy, disrespectful, dramatic.

To risk starting an argument that would become very serious, very fast.

And because of that, my grandmother had gotten eight more hours.

Eight hours in which she squeezed my hand.

Looked at my mother.

Moved her lips around my name.

Eight hours in which I could tell her one more time that I loved her.

Thank her.

Promise her I’d plant cilantro in the spring.

Eight hours I wouldn’t trade for anything.

Not even the comfort of a neat, tidy funeral.

Not even the convenience of avoiding a complicated conversation about life and death and fallible doctors.

Not even the approval of relatives who would’ve preferred I keep my daughter quiet.

Sometimes, I realized, silence is the real sin.

Not speaking up when something feels wrong.

Not asking the question.

Not making the phone call.

Not pointing at the impossible and saying, “I see it anyway.”

My daughter had taught me that.

My grandmother had confirmed it.

The rest of my life, I decided, I would try to remember.

If a little girl can stop a funeral by yelling the truth, maybe I could stop apologizing for mine.

For my boundaries.

For my questions.

For my need to make noise in rooms that prefer quiet.

When people told the story later—because of course they did—it changed with every retelling.

Some said my grandmother had “risen from the dead.”

Some said she’d been “buried alive.”

Some said it was a miracle.

Some said it was a medical fluke.

Some said it was proof the hospital was incompetent.

Some said it was proof God still moved.

Some said it was fake.

Some said we’d all been in shock.

But in the versions I told my daughter, and myself, one thing never changed.

“That day,” I’d say, “you stood up when everyone else was sitting down. You saw what nobody else saw. You shouted what nobody else dared to say. And because of that, we got to say goodbye the right way.”

She’d smile, a little embarrassed.

“I just pointed,” she’d say.

“Sometimes,” I’d reply, “that’s all it takes.”

Sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is point at a closed door and say, “Open it.”

At a signed form and say, “Check again.”

At a still chest and say, “Watch.”

At your own life and say, “This isn’t over.”

At yourself in the mirror and say, “I’m still here.”

Even when everyone else has decided you’re done.

Even when the music has started and the flowers are wilting and the coffin is halfway closed.

Even then.

Especially then.

“Mom?” Sofía asked me a few weeks later, as we watered the little herb garden we’d planted on our apartment balcony.

“Yeah?” I said.

“Do you think Abuela knows?” she asked.

“Knows what?” I asked.

“That I yelled,” she said. “That I… stopped her funeral. That I made everybody mad.”

I smiled.

“I think,” I said, “she’s very proud of you. I think she’s up there bossing angels around, telling them, ‘That one? That’s mine. Don’t you dare shush her.’”

Sofía giggled.

“Good,” she said. “I don’t like being shushed.”

I squeezed her hand.

“Me either,” I said.

Not anymore.

THE END

News

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After a Local Gang Started Harassing Her, but When Their Leader Mocked…

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,”

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,” then learned her attorney was also her secret…

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog Cornered Him Against the Wall and She Called Him “Dramatic,” but…

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying “Lucky for You I Came Back,” She Thought I’d Be…

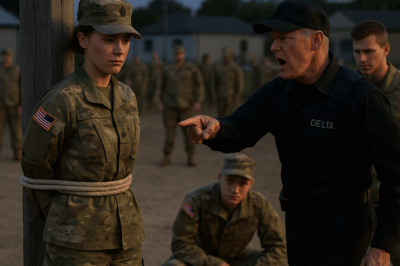

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any Humiliating Order to Protect Her Record, Yet the Moment He Tried…

They thought it was funny to tie the quiet woman in their

They thought it was funny to tie the quiet woman in their platoon to a pole, until a Delta Force…

End of content

No more pages to load