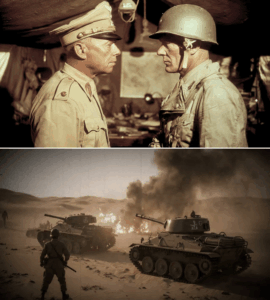

On a Wind-Scoured Ridge in Tunisia, Erwin Rommel Watched His Panzers Halt, Realized an American Cavalryman Had Just Stolen His Favorite Trick, and Murmured the One Line His Staff Never Forgot

By the spring of 1943, the desert did not belong to anyone.

The sand and rock of southern Tunisia had seen too much—Italian infantry collapsing under bombardment, British armored brigades grinding forward and backward like a pendulum, American units learning at terrible cost that enthusiasm alone did not stop panzers.

The maps on headquarters tables in Tunis and Algiers made it look simple. Lines, arrows, objectives. Kasserine Pass here, Gafsa there, El Guettar a smudge between.

Out on the ground, it was something else.

Out on the ground, it was heat and dust and bad roads and worse water, and the knowledge that any rise you crested might be the last one you saw.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had learned that language the hard way in Libya and Egypt. He knew the feel of a battlefield like other men knew the feel of their own handwriting. He could sense, sometimes, where the enemy would break just by listening to his engines and guns and the voices of his men over the crackling radio.

It was why they called him the Wüstenfuchs—the Desert Fox. Not because he was invincible. Because he was patient, quick, and entirely at home in a land that killed the unwary long before the bullets arrived.

On the morning he faced George S. Patton’s reformed Americans near El Guettar, the Fox felt something he did not often feel before a battle.

He felt uncertainty.

At 06:30, on a rocky spur overlooking the rolling valley, Rommel stood with his field glasses pressed to his eyes and watched the American lines through the shimmer of rising heat.

Behind him, a staff car idled, its driver fanning himself with his cap. A cluster of staff officers studied a map spread on the hood, pencils tapping nervously.

General Bayerlein, his chief of staff, cleared his throat.

“Panzers are assembled behind the low ridge,” Bayerlein said. “Ten minutes to H-hour, Herr Feldmarschall. We strike straight down this valley. Their II Corps will not withstand the shock.”

Rommel did not answer immediately.

His gaze traced the American position—the line of low hills, the wadis (dry gullies) cutting across the valley floor, the small, dark specks that were tanks dug in hull-down or artillery barrels angled just so.

He’d fought Americans now. At Kasserine, he had seen their strengths: energy, excellent equipment, bravery in individuals. He had also seen their weaknesses: confusion, lax security, officers unsure of how to coordinate under pressure.

He had exploited that.

Today, he was not sure the same weaknesses remained.

“Remind me,” he said quietly, lowering the glasses. “This new American corps commander… Carter?”

“Patton, Herr Feldmarschall,” Bayerlein corrected. “Lieutenant General George Patton. Formerly armored corps in Morocco and Algeria.”

Rommel nodded slowly.

“Ah yes,” he said. “The one with the pistols.”

Bayerlein allowed himself a brief, tight smile. “Our intelligence says he is… flamboyant,” he said. “But impulsive. The Americans put on a show, but they are still tactically naive. They lack your experience.”

“Experience is a teacher,” Rommel said. “So is being hit hard. They were hit. We must assume they listened.”

He turned back to the valley.

The Americans had dug in well, he noticed. Their artillery was carefully sited, not bunched. Their anti-tank guns were camouflaged, not sitting in the obvious places that shouted “Shoot me!” to any Luftwaffe pilot.

He did not like that.

He’d read, as much as he could, every scrap about his enemies, past and present. He knew Patton had commanded tanks in France in 1918, that he considered himself a cavalryman at heart, that he valued speed and shock.

If he had been in Patton’s shoes, with shaken troops and a battered reputation after Kasserine, what would he do?

He’d read Rommel’s own book, for one thing. They’d told him that in Berlin, half amused.

You magnificent bastard, I read your book.

Rommel had smiled thinly at that report. A compliment, of sorts. Also a warning.

“When the blow falls,” Rommel said quietly to Bayerlein, “they must feel it quickly. Before they can disentangle their guns and pull back. The key is to break their artillery. Break that, and their infantry is meat.”

“Yes, Herr Feldmarschall,” Bayerlein said. “Our plan reflects that. The main thrust down the center, with a feint here to draw their fire.”

He pointed at the map.

Rommel nodded. It was a good plan. A Rommel plan.

He had written something similar years earlier, in his study of infantry attacks: “The main principle is surprise. You attack where he is strong in order to mislead him, then you hit where he is weakest.”

He raised his glasses again.

Down below, American trucks moved in ant trails along the ridges. Not away from the front. Sideways. Repositioning.

“You see that?” he asked.

Bayerlein squinted. “Reinforcing. Or redeploying,” he said. “They may be nervous.”

“Or they may be ready,” Rommel replied.

He lowered the glasses one last time.

“Very well,” he said. “Send the order. We begin.”

On the other side of the valley, in a command halftrack that smelled of coffee and sweat and dust, George S. Patton Jr. tugged his helmet down a fraction of an inch and tapped the map with the butt of a riding crop.

“Rommel’s going to come straight down this bowl,” he said. “It’s what I’d do. Classic move. He thinks we’re still the same outfit he hit at Kasserine. We ain’t.”

Around him, American officers leaned in.

They’d been up all night, checking coordinates, adjusting fire plans, arguing over whether to put another anti-tank gun on that knoll or in the wadi.

Patton, for all his theatrics, had forced them to think.

He’d hammered the basics into them: helmets on, units clearly marked, orders understood more than one echelon down. He’d driven through the lines, stopping at outposts to ask sergeants—not just captains—“What are you doing if krauts come here? What’s your sector? Who’s covering your flank?”

At first, the answers had been blank stares. Then they’d improved.

Now, on this morning, he had something he had not enjoyed at Kasserine.

He had a plan.

“We let him come in,” Patton said. “We let him think we’re going to try to stop him with tanks in the open. We don’t. We stop him with artillery. Lots of it.”

He jabbed the map where his artillery positions were marked.

“Every gun we got is zeroed on this valley floor,” he said. “We fire by time on target—everything lands at once. I don’t want a pretty drumroll. I want a damn door slammed in their faces.”

Colonel Muller, his artillery chief, nodded.

“Firing tables are ready,” Muller said. “Observers are in place. We’ll need good comms.”

“You’ll have them,” Patton said. “Signal corps has been up those hills laying wire like they’re knitting a sweater. Even if the radios cut, we still got phones.”

He glanced up through the open hatch.

The sky was clear. No clouds. Good.

He’d read Rommel, all right. He knew the man loved to use air as much as ground.

“Rommel’s clever,” Patton said, more to himself than to the room. “But he’s also proud. He trusts his instinct. We’re going to lure that instinct into a kill zone and kick its teeth out.”

He looked around at his officers.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “this is where we stop being the outfit that got slapped and start being the outfit that slaps back.”

Someone chuckled nervously.

Patton didn’t.

He felt the same jitters everyone else felt—the awareness that hundreds of lives hung on decisions made in this metal box.

He simply didn’t let it show.

“Get to your posts,” he said. “When Rommel comes, I want him to think we’re crawling in confusion. Then I want him to realize, all at once, that we’ve been waiting.”

The first German shells fell on outlying American positions at 07:45.

They weren’t heavy—probing fire, mostly. Testing reactions, seeing who flinched.

Some American units still flinched.

Patton heard over the net about a platoon that had pulled back five hundred yards without orders. He swore, ordered them back into place, sent one of his staff majors forward to make damn sure they stayed.

He knew one skittish withdrawal could ripple into a general sag, which would ripple into collapse. He wasn’t about to let that happen again.

At 08:10, observers on the ridge called down the line everyone had been waiting for.

“Armor, lots of it. Dust cloud on the far side. Range… closing.”

Rommel’s panzers were on the move.

On the ridge, Rommel stood in his command car, binoculars glued to his face.

“Advance,” he said into the radio. “Schwerpunkt here. Keep moving. Don’t stop for small arms fire. The longer you sit, the more they see you.”

Tracked vehicles clawed forward—Panzer IVs mostly, with some long-barreled Mark IIIs still in the mix. They’d been reinforced with newer models since earlier fights, but there weren’t as many as Rommel would have liked.

Fuel shortages, replacement issues, Berlin promising more than it shipped.

He would make do.

Dust rose in a great brown wall behind the formation.

“That will make their observers’ work harder,” Bayerlein said.

“It will also show them exactly where we are,” Rommel replied. “We must move through the killing ground quickly. Their artillery is our worst enemy here.”

He’d written that, too, in his book. Artillery, he’d learned in the First World War, killed more men than rifles ever dreamed of.

He didn’t know yet that on the other side, a man who had read those lines was betting heavily that he meant it.

At 08:23, Patton stood with one boot on the bumper of his command halftrack, headset on, and listened as the observers called in ranges and bearings.

“Main body entering grid… tanks in column… infantry following close…”

“Let ’em come,” Patton said, mostly for the benefit of the men around him. “Don’t shoot early. They gotta commit. This is a poker game, boys. You don’t tip your hand before they shove their chips in the pot.”

Muller checked his watch.

“Another minute,” he murmured. “We want as many in the bowl as we can.”

Through his glasses, Patton could see the German tanks now—dark shapes against the pale ground, spreading a little as they advanced, then bunching where the terrain forced them.

He’d deliberately left one of the obvious ridges thinly held—just enough to make noise, not enough to look formidable.

“Rommel’s book,” he’d told his staff the night before, “says you hit where he thinks you’re weak. We’re going to give him a nice juicy weak spot that’s actually a trap.”

On the ridge, a company of American tanks revved engines, moved, backed, moved again—showing themselves just long enough to draw attention, then ducking out of sight.

Rommel saw that, of course.

“There,” he said, pointing. “They’re thin on that ridge. They have armor, but not enough. If we push hard there, we’ll roll them up.”

Bayerlein nodded, relaying orders to shift heavier elements slightly toward that seam.

They were doing exactly what Patton hoped they’d do.

At 08:28, Muller nodded to Patton.

“Time on target,” he said.

Patton keyed his microphone.

“All batteries, this is Corps,” he said. “Execute. Fire. Fire. Fire.”

Later, men would struggle to describe the sound.

It wasn’t any one gun. It was all of them.

American artillery behind the lines—105s, 155s, and everything else they could roll into position—fired in carefully timed sequence so that their shells, though launched from different distances, would arrive over the valley at the same instant.

To the Germans below, there was no warning drumroll, no gradual increase.

One second, there was dust and engine noise and the distant crackle of small arms.

The next, the sky fell.

Shells exploded among the leading tanks, on the infantry walking behind, on half-tracks full of ammunition. The first salvo tore into the column like a giant had raked its fingers through a line of toy soldiers.

Rommel flinched.

He’d expected artillery. He always expected artillery.

He had not expected this.

Shell after shell rained down, not on some random patch of ground, but precisely in the kill zone where the majority of his advancing force had just entered.

His radio exploded with voices.

“Hits! Multiple hits!”

“Three tanks knocked—”

“Smoke everywhere—”

“Infantry taking heavy casualties—”

“Do we push or pull back?” a battalion commander demanded, voice tight.

Rommel tasted dust in his mouth. A gust of wind brought the smell of explosive and something else—hot metal, burning rubber.

He forced himself to think in long lines, not short spasms.

They had committed. Pulling back meant reversing under fire, always a dangerous move. Pushing meant moving through hell.

He’d written about this too—the need to keep going, even when his men wanted to hug the dirt.

“Their artillery is well-sited,” he said to Bayerlein, voice calm. “Better than before. They have learned. We continue. Order them: forward. Scatter, but forward. We must get out of this concentration.”

Bayerlein relayed the order.

Panzers lurched, some spouting smoke, others still solid. They fanned out as much as the terrain allowed, gunners hosing fire at the ridges in hopes of silencing some of the enemy guns.

American observers, dug in on those ridges, adjusted their tubes.

“Walk it fifty meters,” one said into his handset. “They’re trying to skirt. Don’t let ’em.”

In the command halftrack, Patton listened to the reports and snarled approvingly.

“That’s it,” he said. “Keep the pressure on. Don’t let them catch their breath.”

He thought of Rommel reading the ground, looking for the telltale signs of weakness. He thought of the man’s reputation for finding gaps.

“Not today,” he muttered. “Today you get the edge of the board.”

On the ridge, Rommel watched one of his lead companies stagger.

Two tanks took direct hits on the glacis and lurched to a halt, crews scrambling out, some on fire, some stunned. A third stuck a track in a crater, tried to twist out, and exposed its thinner side armor to another jagged plume of shellburst.

Infantry hugged the ground, pinned.

He had seen worse. He had seen columns gutted by British guns in the desert, had watched his own attacks falter under barrages that felt like someone pounding nails into the earth.

But there was something else here that nagged at him.

The American fire wasn’t just heavy.

It was coordinated.

Patterns emerged in the chaos—shifts that matched his shifts, concentrations where they would do the most damage, quick lulls followed by sudden intensifications.

“Good fire discipline,” he said aloud, almost to himself. “They are not panicking. They are adjusting.”

Bayerlein, sweating despite the morning chill, wiped his brow.

“We could swing left,” Bayerlein suggested. “Try to outflank them. Or pull back and seek another axis.”

Rommel shook his head.

“The ground dictates,” he said. “That valley is the route. Elsewhere is worse. And every minute we delay gives them more time to dig in further.”

He ground his teeth.

“This is not like before,” he said. “They are not scattering.”

He lifted his glasses again.

On the American ridge, he thought he saw movement—a line of muzzle flashes, offset and regular.

It reminded him, perversely, of something he had written about his own methods.

“Attack where the enemy does not expect you,” he had once advised. “Use surprise, speed, and concentrated fire.”

He lowered the glasses.

“I believe,” he said quietly, “that whoever commands them has read my book.”

Bayerlein glanced at him sideways.

“Herr Feldmarschall?” he asked.

Rommel didn’t reply. He was watching another salvo crash down, dust and smoke obscuring the valley floor.

In that moment, on that ridge, he knew two things:

His attack would not achieve what he had hoped.

And somewhere over there, in that tangle of ridges and gullies and determined men, there was an American general who had decided, consciously, to use Rommel’s own principles against him.

He could not help it.

He felt a flicker of professional respect—and, beneath it, professional annoyance.

“Forward,” he said again into the radio, though he knew, now, that “forward” meant “forward far enough to disengage in some order, not forward to victory.”

The Desert Fox did not like retreat.

He liked being outfoxed even less.

By midday, the attack had stalled.

The Germans had penetrated into the valley, yes. They had created pockets of chaos, overrun some American forward positions, knocked out plenty of guns and tanks.

But they had not broken II Corps.

American artillery had done something that Rommel’s British opponents had only occasionally managed in North Africa: it had turned open ground into a killing field in which tanks were not predators, but prey.

Patton, aware of the temptation to chase, restrained his armor.

“We don’t go charging out there after them,” he told his staff. “They want us to stick our necks out so they can whack us with air and long guns. We let them pull back. Then we push our line forward, methodical. Artillery first, tanks in support. Let them feel how it is to be on the receiving end of a well-placed punch.”

He paused, then added with a thin grin, “Rommel will not be feeling cocky tonight, I promise you that.”

On the German side, Rommel already knew.

By 13:00, he ordered the attack broken off.

The radio crackled with acknowledgements tinged with disappointment, frustration, and relief.

He watched his panzers reverse, some dragging crippled comrades, some leaving burning wrecks behind. Smoke marked the path of the engagement like a long, ragged scar.

Bayerlein looked at him.

“Herr Feldmarschall,” he said, “shall I draft the report for OKW? They will not be pleased.”

Rommel gave a humorless little smile.

“They are rarely pleased,” he said. “They sit in Berlin and draw arrows, and expect the world to obey. Today, the world did not.”

He shaded his eyes with one hand, watching an American artillery position still firing occasional shells, more in harassment than in earnest.

“They will say we should have done better,” he went on. “That the Americans are amateurs, that we are Aryan supermen, that with enough ideology, we can overcome numbers and guns.”

His mouth twisted.

“Today,” he said, “I saw Americans fight like veterans. And I saw our men bleed like anyone else.”

He turned to Bayerlein.

“Write the truth,” Rommel said. “Tell them the attack was repulsed by heavy, accurate artillery fire from well-prepared positions. Tell them the enemy commander handled his forces intelligently.”

Bayerlein hesitated.

“Name him?” he asked.

Rommel looked back toward the ridges, as if expecting to see Patton there, standing with binoculars and that damned polished helmet.

“Yes,” he said quietly. “It is time Berlin learned a name they have been underestimating.”

He spoke it as if tasting something bitter and interesting.

“Patton,” Rommel said. “General Patton gave us a lesson today.”

He paused, then added, almost under his breath, “He learned from me. And then he improved the lesson.”

Bayerlein, pen poised over his notebook, glanced up.

“What shall I write for your personal comment, Herr Feldmarschall?” he asked. “They will expect one.”

Rommel considered.

He thought of the saying the British used—“give the devil his due”—and of how rare it was, in any army, for one professional to publicly acknowledge another on the opposite side.

He thought of his own pride. Of his image. Of the myth that had grown around the Desert Fox.

Then he thought of how that morning had felt, watching his tanks run into a storm someone had very carefully prepared for them.

“Write this,” he said at last. “Quote me exactly.”

He waited until he was sure Bayerlein was ready.

“The Americans,” Rommel said, “have finally found a general who knows how to fight in the desert.”

He let that hang for a beat.

“His name,” he finished, “is Patton.”

Bayerlein wrote it down.

In Berlin, the report would be read, dissected, perhaps dismissed as an old Afrikakorps commander making excuses.

But among those who knew what it meant to read a battlefield, the weight of that sentence would not be lost.

Rommel’s staff, standing nearby, heard it.

Later, in POW camps or in staff positions far from the front, they would repeat it to their counterparts.

“The Field Marshal,” they’d say, “he said the Americans had found their desert general. Patton. He was… impressed.”

Not pleased. Not happy.

But impressed.

On the American side, Patton never heard the exact words in the moment.

He was too busy.

Too busy checking positions, visiting wounded, chewing out a captain who had refused to move a gun line forward because it was “too risky,” boosting the morale of a battered infantry battalion by telling them, in his own crude way, that they had done damn well and that he’d rather have them than any parade-ground dandies.

It was only later—months, maybe years later—that someone, somewhere, passed along a translated copy of Rommel’s comment.

Patton read it in silence, the paper crackling faintly in his hand.

“He said that?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” the intelligence officer replied. “That’s the translation. ‘The Americans have finally found a general who knows how to fight in the desert. His name is Patton.’”

Patton grunted.

“That’s not exactly ‘you magnificent bastard,’” he said.

“No, sir,” the officer said, smiling.

“But it’ll do,” Patton added.

He folded the paper carefully, slid it into the pocket of his jacket where he kept other small, personal tokens—pictures, notes, a card with a prayer on it.

“Field Marshal Rommel was no pushover,” Patton said. “When a man like that says you know what you’re doing, you frame it. Or at least you don’t throw it away.”

He wasn’t naive.

He knew Rommel would have gladly killed every one of his men if the battle had turned differently.

Respect in war did not mean softness.

But it meant something.

Years later, after the war had burned itself out and the maps on the walls of Europe had been redrawn in ways that no one in 1939 could have entirely predicted, historians would write about that day in Tunisia.

They’d argue about how much Patton himself had directly influenced the artillery plan versus his subordinates. They’d note that Rommel was ill, that his resources were stretched, that the Afrika Korps was a shadow of its former self.

They’d debate whether Rommel had actually said those exact words, or something like them, or something that later grew into that line in the telling.

But the men who had been there—on the ridges, in the valleys, in the command cars and halftracks—remembered it as real.

They remembered, in particular, how Rommel had looked that morning: binoculars up, face set, then finally—just for a heartbeat—eyes narrowing in what could only be called reluctant admiration.

In that moment, the Desert Fox had recognized another hunter.

One who had read his tracks.

One who had learned.

One who, on that day at least, had outsmarted him on his own kind of ground.

“What did Rommel say?” people would ask.

“He said,” the veterans would reply, “that we’d found our general.”

And somewhere in the long, complicated ledger of that war, on a page marked “Desert,” two names would sit closer together than either man, in life, might have liked to admit:

Rommel.

Patton.

Each, in his own language, acknowledging that the other was the kind of enemy you could respect even as you tried very hard to kill him.

THE END

News

They Flaunted Their Wealth, Mocked the Tip Jar, and Flat-Out Refused to Pay the Waitress — Until the Quiet Man at the Corner Booth Revealed He Was the Billionaire Owner Listening the Whole Time

They Flaunted Their Wealth, Mocked the Tip Jar, and Flat-Out Refused to Pay the Waitress — Until the Quiet Man…

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her Laughed—Until the Screen Changed, and the Truth Sparked the Hardest Argument of His Life

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her…

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind the $600 Million Deal That Was About to Decide Every One of Their Jobs and Futures

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind…

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the Millionaire in Line Behind Him Heard Everything—and What Happened Next Tested Pride, Policy, and the True Meaning of Help

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the…

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up a Doll, Looked Under the Bed, and Uncovered a Hidden “Secret” That Nearly Blew the Family Apart for Good

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up…

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really on His Plate and the Argument That Followed Changed Everything About What He Thought Money Could Buy

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really…

End of content

No more pages to load