Nearly Lost on a Winter Night in War-Torn Germany, a Young Nurse Was Saved by an American Doctor—Decades Later, Her Quiet Promise Created an Army of 10,000 Healers Worldwide

The night Elise almost died began in silence.

Not peaceful silence—this was the heavy, exhausted quiet that comes after shouting and sirens and running. It was the kind of quiet that made every sound feel too loud, every breath a minor crime.

The small field hospital on the edge of town had once been a school. The classrooms now held rows of cots instead of desks, metal trays instead of blackboards. The chalk dust had been replaced by the faint smell of antiseptic and something heavier, something Elise tried not to think about when she moved from bed to bed.

She was twenty-three and had been a nurse for only a year. Her hands had learned to move quickly, to roll bandages and take pulses, to lift without shaking and smile without breaking. Her heart, on the other hand, was still learning what to do with all it had seen.

That night the cold crept in through the cracks around the windows. The small stove in the corner burned just enough fuel to keep the worst of the frost away, but not enough to make anyone truly warm. Elise rubbed her hands together as she finished checking on an old man with a weak heart, then pulled her thin sweater tighter around her uniform.

“Go to bed, Fräulein,” the man whispered, his voice scratchy. “You look more tired than I feel.”

Elise smiled. “If I sleep, who will bother you for your pulse every hour?”

He chuckled weakly. “I suppose you’re right. But still… you are human, not a machine.”

She moved on without answering. Human, she thought. Some days, she wasn’t so sure. Human beings were not meant to move on after certain sights, certain sounds—and yet every morning she woke up and did it again.

By midnight, the hospital had settled into a fragile calm. A few patients moaned softly in their sleep; someone coughed in the next room. Outside, the wind slid along the broken walls, making the old building shudder.

The first sign of trouble was small.

Elise was in the supply closet, counting the remaining rolls of bandages by the light of a single lamp, when a sharp pain stabbed the left side of her head. It was sudden and bright, as if someone had pressed a hot needle into her temple.

She gasped and grabbed the edge of the shelf.

“Not now,” she muttered under her breath. “Please, not now.”

The headaches had started months ago. At first they were rare—a dull ache at the end of a long day. Then they became more frequent, sharper, arriving with little warning. Each time, she told herself it was just fatigue, just stress, just… everything.

She told no one. There was too much else to worry about. Patients needed her. Colleagues relied on her. The town had too few nurses as it was.

So she pushed through. She drank more water, slept when she could, pressed cool cloths to her forehead and kept going.

But tonight, the pain was different.

It spread quickly from her temple to the back of her head, then down her neck. The room seemed to tilt. The lamp light flared too bright, then too dim.

Elise closed her eyes and tried to breathe steadily. “Just a moment,” she whispered. “Just rest for a moment, and it will pass.”

She straightened, took one step toward the door—and her right leg buckled.

She crashed into the shelf, knocking a stack of gauze to the floor. A tin tray clattered noisily, the sound echoing down the hallway.

“Elise?” someone called. “Alles in Ordnung?”

She tried to answer, but the words tangled somewhere between her brain and her mouth. Her tongue felt heavy, uncooperative. When she finally managed a sound, it came out slurred and strange.

The world blurred at the edges. The lamp’s small flame stretched into a halo.

Then everything dropped away.

When she woke, the ceiling above her was not familiar.

At first she thought she was in another ward of the hospital, but the paint here was different, cleaner. The lights were brighter. The air didn’t smell like damp plaster and coal smoke; it smelled like soap and something sharp and sterile.

She tried to sit up. Her body refused.

Panic rose in her chest. Her right arm lay useless at her side, heavy and distant, as if it belonged to someone else. She tried again, focusing all her will on her fingers.

Nothing.

Her heart sped up. She looked toward the door for help, but even that small movement made her dizzy.

“Easy there.”

The voice came from her left, warm and steady, with a cadence she didn’t recognize. The words were in German, but the accent was not.

She turned her head, slowly this time.

A man sat on a stool beside her bed. His uniform was unfamiliar: olive-colored, with patches she had never seen. His hair was dark and just a little too long, curling slightly at the collar. A pair of wire-rimmed glasses rested on his nose, and his eyes—tired but alert—studied her carefully.

An American, she realized.

Elise’s heart thudded once, hard.

The rumor had spread through town like a storm: American troops had arrived. People whispered about them in doorways and kitchens. Some spoke with fear, others with cautious hope. In the hospital, the doctors had talked in low voices long after the patients were asleep.

“Do you understand me?” the man asked, still in careful German. “My name is Daniel Carter. I’m a doctor.”

He pronounced “Carter” like “Kah-ter,” the foreign name softened for her language.

Elise swallowed. Her throat felt dry. “I… understand,” she managed. Her own voice sounded unfamiliar to her, slower on one side, as if half her mouth had forgotten how to shape words.

The doctor nodded, making a quick note on a clipboard. “Good. You gave us quite a scare.”

“What… happened?” she asked.

He hesitated, as if choosing his words.

“You collapsed,” he said gently. “Your colleagues brought you in. You’ve been here for two days.”

Two days. The number landed like a stone in her stomach. Two days away from the ward, from her patients, from the fragile rhythm of work that kept her anchored.

“I must go back,” she said, trying again to sit up. “They need—”

Her body refused once more. Her right arm lay still. Panic flickered in her eyes.

Dr. Carter held up a calming hand. “Stop. Please. Listen to me.”

She froze, breathing fast.

“You’ve had what we call a stroke,” he continued, his voice calm but firm. “A blood vessel in your brain was blocked. Part of your body is affected—your right side. That’s why it feels weak.”

His words gathered like storm clouds over her head.

Stroke.

She knew the word. She had seen patients with twisted smiles and dragging feet, had helped them learn to walk again, to lift a spoon, to smile without tears. She had comforted families who cried in doorways, told them there was hope if they were patient and strong.

She had never imagined standing—lying—on the other side of that conversation.

“No,” she whispered. “I… I am young. I work. I cannot…”

Her voice broke.

He didn’t look away. “I know,” he said. “It doesn’t seem fair. It isn’t fair. But it happened. The good news is you were brought in quickly. That gives us a chance.”

“A chance?” she repeated.

“To get some function back,” he explained. “Maybe a lot. The brain is stubborn, but it can also adapt. It needs time. It needs work. It needs you to fight for it.”

She stared at him. American or not, his words were the same kind of truth she had spoken to others. But they felt different pointed at her.

“I have patients,” she said dully. “Old Herr Klauss with the bad heart. Little Marta with the fever. If I am here, who will—”

“Right now, you are the patient,” he said gently but firmly. “Others are taking care of your ward. Your job is to let us take care of you.”

The idea seemed almost offensive. She had built her identity around being the one who showed up, who steadied other people’s hands, who listened and soothed. To be reduced to the flat figure under the sheet felt like a kind of theft.

He seemed to read some of that on her face.

“I’ve been told you’re a good nurse,” he added. “Your colleagues fought to get you here when they heard there were American doctors working in the region. That tells me something.”

She blinked. “They… fought?”

He smiled slightly. “Argued. Persuaded. Made a lot of noise. Whatever word you prefer.”

The image warmed her, even in her fear: her fellow nurses pushing through red tape, insisting she be given care as urgently as any patient.

“They believe you’re worth saving,” Dr. Carter said quietly. “So do I. But you have to help.”

“How?” she asked hoarsely.

“By not giving up,” he replied. “By doing the work we’re going to ask of you. It won’t be easy. But I’ve seen people come back from worse. You’re young. You’re stubborn—I can see it already. That’s in your favor.”

Her eyes pricked with unexpected tears.

For a long moment, neither of them spoke. The sounds of the ward—the distant murmur of voices, the squeak of a stretcher wheel—faded into the background hum of the new, uncertain world she’d woken into.

Finally, she found her voice again.

“Will I ever… be able to work as a nurse again?” she asked.

It was the question that mattered most. Her identity, her purpose, her reason for getting out of bed each morning—they were all wrapped up in that single word: nurse.

Dr. Carter didn’t rush his answer.

“I can’t promise you exactly what you’ll gain back,” he said slowly. “Medicine doesn’t come with guarantees. But I can tell you this: if we start rehabilitation early, if you work hard and we support you well… there is a very real chance you will be able to go back to caring for others. Maybe not exactly the same way. But in your own way.”

“In my own way,” she repeated softly.

“Yes,” he said. “For now, your job is simple. You will rest. You will let other people fuss over you. And tomorrow, if you’re strong enough, we begin.”

“Begin what?” she asked.

He smiled—a real, warm smile that reached his eyes. “We begin teaching your brain to write with its left hand what it used to write with its right.”

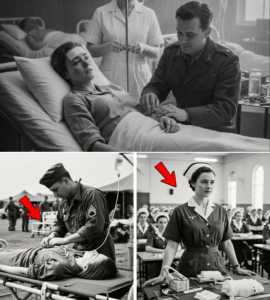

Rehabilitation was nothing like the soft, hopeful montages Elise had imagined for her patients when she sent them home. It was slow. It was awkward. It was humiliating.

The first task seemed absurd: lifting a small wooden block from one side of a tray to the other using her less-dominant hand.

“Elbow off the table,” the therapist, a brisk woman named Greta, instructed. “Use your shoulder. No, not like that. Here.”

She guided Elise’s arm, gently but firmly.

Elise’s muscles trembled with effort. Sweat gathered at her hairline. Her fingers refused to curl properly, her grip weak. The block slipped and fell back to the tray with a dull clack.

Tears of frustration burned behind her eyes.

“I used to carry two buckets of water at once,” she muttered. “Now I cannot lift a toy.”

“Once upon a time, you could not even roll over by yourself,” Greta replied, not unkindly. “You learned that. You will learn this, too.”

Elise scowled. The comparison to a baby stung—but it was not wrong.

Outside of therapy, Dr. Carter visited daily. Sometimes he checked her reflexes and reviewed her progress, his touch clinical but careful. Other times he simply sat by her bed, asking about her life before her illness.

“Why nursing?” he asked once, unfolding a small notebook.

She shrugged, her left shoulder rising. “I wanted to do something that did not destroy,” she said. “Everything around us was breaking. I thought… maybe I can help hold some things together.”

“That’s a good reason,” he said.

“Why did you become a doctor?” she asked.

He chuckled softly. “I grew up in a small town. We had one doctor who did everything—deliver babies, set broken arms, scold people who worked too hard. He seemed to be there in every important moment of people’s lives. I wanted that, I guess.”

“And now you are here,” she said.

“Now I’m here,” he agreed. “Not exactly the career path I imagined. But sometimes life takes the scenic route.”

His attempts at humor were not always funny, but they were steadying. They anchored their conversations in something other than illness and war. He spoke of Ohio—long, flat fields, wide skies, summers thick with humidity and the sound of cicadas. She spoke of her childhood in a German town with cobbled streets and a river that glittered on sunny days.

Slowly, the barrier between “German” and “American” thinned, replaced by “patient” and “doctor,” “woman” and “man,” two people sharing stories because the world had placed them in the same room and said, Deal with this together.

Weeks passed. The wooden blocks gave way to more complex tasks: buttons, laces, a pen held clumsily in her left hand. Walking came back in fits and starts, first with support, then with a cane, then with nothing but her own stubborn balance.

Her right arm remained stubbornly weaker than the rest of her body, slow to respond. But her speech improved, the stiffness at the corner of her mouth easing as her brain forged new pathways.

One morning, she managed to tie the belt of her robe by herself.

It was a small victory, but it made her feel like she’d climbed a mountain.

“Look,” she said when Dr. Carter entered the room. “No help.”

He examined the knot with exaggerated seriousness. “Flawless,” he pronounced. “Ten out of ten.”

She laughed. “You are mocking me.”

“Not at all,” he said. “Tying a robe is a highly underrated skill. Trust me, I’ve seen plenty of people who can’t manage it.”

“You see plenty of people who cannot read their own prescriptions,” she countered.

“Exactly,” he said. “That’s why they need nurses like you.”

The word “nurse” sent a sharp ache of longing through her chest.

“You think I can go back?” she asked quietly. It was not the first time she’d asked, but the question still felt fragile, as if the wrong answer might shatter it completely.

He met her eyes. “I don’t just think it,” he said. “I am planning for it.”

“You are planning?” she repeated.

“Yes,” he said. “In fact, I’ve been thinking about something. When you’re ready, of course. Not tomorrow. Not next week. Later.”

“What is it?” she asked.

He glanced at the door, then back at her, lowering his voice slightly.

“The local hospital is short on staff,” he said. “Short on supplies, short on training, short on everything. Right now, people patch things together as best they can. But this region needs more nurses. Properly trained, well-prepared nurses. Not just now, but for years to come.”

She nodded. “We talk about it often. But we do not have enough resources.”

“Maybe you don’t need as much as you think,” he said. “Here’s my thought: we start small. A training program. A course. A place where experienced nurses share what they know with younger ones. Nothing fancy. Just a room, a few beds, some textbooks—”

“Textbooks,” she echoed, amused. “You think we have shelves of those hidden somewhere?”

“Let me worry about the books,” he said. “The Army has warehouses full of things they don’t know what to do with. If I ask the right people, we might pry a few boxes loose.”

“And who will teach these nurses?” she asked, skeptical. “We are already tired. Overworked.”

He gave her a pointed look.

“You will,” he said.

She blinked. “Me?”

“Yes, you.”

She shook her head incredulously. “I can barely tie my robe.”

“And yet you tied it,” he countered. “You’ve been a nurse through some of the hardest conditions imaginable. You’ve survived your own illness. That means you understand both sides of the bed. That’s rare. That’s valuable.”

His words sank into the space between them like seeds dropping into soil.

“You want me to… teach?” she said slowly. “Train nurses?”

“I want you to consider it,” he said. “Think about it this way: when you were lying here, frightened and frustrated, what helped most?”

She thought. “Being told the truth,” she said. “Not being treated like… like a broken thing to be pushed aside. Having someone believe I could get better. Even when I did not believe it myself.”

He nodded. “Imagine if every nurse in this region treated their patients that way. Imagine how many lives would feel different. Imagine how many families would remember their nurse’s face, not just their fear.”

She looked down at her hands. Her left hand, once clumsy, now lay steady on the blanket. Her right hand, still weaker, twitched as she willed her fingers to curl.

“Why me?” she whispered.

“Because you know what it’s like to feel helpless and fight your way back,” he said simply. “Because you have already proven you won’t give up easily. And because, if I am being honest, I think this experience will make you an even better nurse than you were before.”

“Even better?” she repeated softly.

“Even better,” he confirmed. “Not in spite of what happened to you, but partly because of it.”

Something shifted inside her at those words. She hadn’t yet considered that her illness might not only take things from her—that it might give her something, too. A new kind of understanding. A different kind of strength.

He stood.

“You don’t have to decide now,” he said. “You can think about it. For tonight, I just want you to rest.”

But long after the lights dimmed and footsteps faded in the hallway, Elise lay awake, staring at the ceiling.

Teach. Train nurses.

She pictured a room of young women in simple uniforms, notebooks in hand, watching her demonstrate how to change a dressing or speak gently to a frightened patient. She imagined explaining what it felt like to be on the receiving end of care, how every small kindness mattered.

The idea scared her.

It also brightened something in her that had gone dull.

That night, she whispered a promise into the darkness—not to any one person, but to the quiet place inside herself where fear and hope had been circling each other since the day of her collapse.

If I am allowed to stand on my own feet again, she murmured silently, if I am given the strength to work… I will not waste it. I will pass it on.

She didn’t yet know how far that promise would reach.

The first class met in a borrowed room above the hospital’s laundry.

The walls were bare except for a faded map someone had tacked up years earlier. The chairs didn’t match. The “lecture table” was just a crate with a clean sheet draped over it. But the fifteen young women who sat in those chairs, backs straight, faces serious, made the room feel like something larger than itself.

Elise stood at the front, her pulse tapping at her wrists.

Her right arm, still weaker than the left, rested casually on the table. She had practiced that position in the mirror until it felt natural. She refused to hide what had happened to her—but she also refused to let it define every first impression.

Dr. Carter sat in the back row, a quiet presence. He had insisted he would only watch for the first session, not interfere.

“You will not be able to stop yourself,” she had warned him.

“I’ll do my best,” he’d replied, smiling.

Now he simply nodded encouragingly when her eyes met his.

“Good morning,” Elise began, her voice a little shaky. “My name is Elise Bauer. Some of you know me from the hospital. Some do not. We are here to learn… and also to unlearn some things.”

A few brows furrowed.

“In difficult times,” she continued, “people learn to be quick. To cut corners. To do what they must to get through the day. That is understandable. But in nursing, speed is not everything. Presence is just as important. How you speak to someone, how you listen, how you touch their arm when you tell them hard news—these things matter.”

She told them briefly about her stroke. Not for pity, but as context.

“I have been on both sides now,” she said. “I have watched patients fight to stand, and I have fought to stand myself. So when I tell you that every small kindness you offer will mean more than you imagine, I speak from experience.”

She began with basics: hygiene, infection control, simple anatomy. She used words that some of the young women had only heard in passing. She broke down complex ideas into clear, practical steps.

“When you wash your hands,” she said, “you are not just removing dirt. You are protecting the next person you will touch.”

“When you change a dressing, do not rush. Pain lives in that wound. The patient watches your face. If you look impatient, they will feel they are a burden.”

She demonstrated how to lift a patient without hurting one’s own back. She showed them how to notice small changes—pale lips, a new cough—that might signal something serious before it exploded into crisis.

At one point, Dr. Carter couldn’t help himself.

“May I add something?” he asked, raising a hand like a polite student.

Elise laughed. “I knew you could not sit quietly the whole time,” she said, as the class smiled.

He stepped to the front and drew a simple picture of a heart on the chalkboard, then sketched out how blood flowed through the body.

“Your work is not just here,” he said, tapping the symbol of the heart. “It is here.” He tapped the sketch of the brain, then his own chest. “And here. You will see people on some of the hardest days of their lives. You are not just tending to their bodies. You’re also tending to their fear.”

When the session ended, the young women didn’t rush to leave. They gathered around Elise with questions that spilled over each other: How do you handle a family that does not want to hear bad news? What do you do when a patient refuses care? How do you keep going when you are tired and sad?

Elise answered as best she could, honestly and without pretending to have every solution.

“You do not have to be perfect,” she said. “You only have to keep trying to be better.”

That first course ran for six weeks. Not everyone finished; some were pulled away by family obligations, some by other jobs. But ten women stayed until the end, receiving simple certificates that Elise wrote by hand.

“You are the first,” she told them at the small ceremony. “Others will follow. When you go to your wards, your clinics, your villages… remember that you are not alone. We stand behind you, and those who will come after will stand with you.”

Dr. Carter stood beside her, clapping. “This is only the beginning,” he said quietly.

He was right.

The years that followed were not easy, but they were forward-moving.

The war’s ruins gradually made room for new buildings. Roads were repaired. Schools reopened. People learned how to live without flinching at every unexpected sound.

The little nursing course grew.

At first, it was still just one room and whoever could be spared from the hospital staff. Then a small grant from an aid organization arrived, thanks to a letter Dr. Carter had sent before he returned to America. The money allowed them to buy proper beds for demonstration, a few anatomical charts, a shelf of donated textbooks in both German and English.

Elise learned to read the English ones slowly, with a dictionary at hand. She underlined terms, made notes in neat handwriting, and then translated the important parts into lessons that made sense to young women who had never left their region.

Her stroke left a permanent faint weakness on her right side. On cold days, her hand stiffened. Sometimes her foot dragged a little when she was tired. But she refused to let these things sideline her.

Instead, she wove her story into the fabric of the school.

“Your bodies may fail you one day,” she told her students. “Your hearts may break. But that does not mean your work must end. It may simply change shape.”

The program expanded from six weeks to three months, then to six. Men began to enroll as well, at first just a few, then more. Some of the earliest graduates returned as instructors, bringing with them stories from rural clinics and city hospitals.

“We saw a child with a breathing problem,” one former student reported to a class. “Because of what I learned here, I recognized the signs early. We got him to a doctor in time. He is alive because of this place.”

Elise listened, eyes bright.

“This place” was now a small but official school.

There was a sign by the door: REGIONAL SCHOOL OF NURSING. It was simple, hand-painted, but to Elise it might as well have been carved in marble. She ran her fingers over the letters the day it was hung, feeling the grain of the wood, the raised edges of possibility.

She wrote letters to Dr. Carter, sending them across the ocean.

We had 32 graduates this year, she reported once. They are working in seven different towns. One has started a small clinic in a village that had none.

He wrote back with stories of his own: a community hospital he had helped build, a training program in his own country inspired partly by what he had seen in hers.

“You once said life takes the scenic route,” she wrote in response. “I think our route has more bends than most. But I am grateful for the road.”

Years turned into decades.

The world changed. New technologies arrived in the hospital: better imaging, more effective medicines, machines that hummed and beeped and flashed. The uniforms changed, too. The crisp white dresses and caps gave way to comfortable trousers and colorful tops.

But some things stayed the same.

Beds still needed to be made. Hands still needed to be held. Families still needed to be told that someone they loved was very sick, and then—sometimes, blessedly—that they would be all right.

Through it all, the school grew.

By the time Elise was in her seventies, the school employed a full staff of instructors, most of them people she herself had once taught. The building had expanded twice. What had started in a laundry loft now occupied a proud, light-filled structure near the main hospital, with classrooms, a skills lab, and even a small library.

One afternoon, the current director—a woman in her forties named Miriam, who had been one of Elise’s brightest students—came into her office carrying a folder.

“I have something to show you,” Miriam said, smiling.

Elise looked up from the notes she was reviewing. Her hair was completely white now, cut short for practicality. The faint droop at one corner of her mouth remained as a quiet echo of her stroke, but her eyes were still sharp.

“What is it?” she asked.

“Our numbers,” Miriam said, handing her the folder. “The tally you asked for.”

Elise opened it.

Inside was a simple chart, neatly printed. It listed, year by year, the number of nurses the school had trained since its official founding.

She traced the first few lines with her finger—ten, twelve, eight. Then the numbers grew: twenty, thirty-five, fifty. Some years were leaner, interrupted by economic downturns or outbreaks of illness. Others swelled with larger classes.

At the bottom of the page, Miriam had written the total.

10,004.

Elise stared at the number.

“Ten thousand,” she whispered. Saying it aloud made it feel even more enormous. “More than ten thousand.”

“Ten thousand and four, to be exact,” Miriam said. “We thought you’d like to know before the ceremony next week.”

“What ceremony?” Elise asked, still caught in the glow of the number.

Miriam laughed softly. “The one where we name this building after you, of course.”

Elise looked up, startled. “That is not necessary.”

“Maybe not necessary,” Miriam said gently. “But deeply deserved.”

Elise shook her head. “This was never just me. You know that. It was you, and the others. The early donors, the volunteers, Dr. Carter…” She paused, emotion flickering across her face. “So many people.”

“Of course,” Miriam agreed. “But someone had to be the first to say, ‘We can do this.’ Someone had to make a promise in a very dark time and then spend decades keeping it.”

Elise looked down at the chart again.

Ten thousand nurses.

Ten thousand people who had walked out of these doors and into wards and clinics and homes. Ten thousand pairs of hands that had learned to lift gently, to listen patiently, to stay calm when everyone else was afraid.

She thought of all the lives those nurses had touched. If each had cared for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of patients in their careers, the number of lives improved, eased, or saved was beyond her ability to calculate.

“Do you remember,” Miriam asked softly, “what you once told us in class? That every nurse carries a little lantern into someone’s darkness?”

Elise smiled faintly. “I talk too much in class,” she said, but her eyes shone.

“Well,” Miriam said, closing the folder, “you lit a lot of lanterns.”

That night, Elise walked home slower than she used to. Her right leg, never fully cooperative, ached more in the cool evening air. But her shoulders were straight.

She passed by the hospital’s front entrance, where a young nurse in modern scrubs was helping an elderly woman out of a car. The nurse bent, spoke softly, adjusted the woman’s scarf. The gestures were timeless.

Further down the street, she saw a group of nursing students leaving the school, laughing and talking, books under their arms. One of them held the door for another without breaking his sentence. Small kindness, automatic and genuine.

She stopped for a moment and just watched.

Somewhere across the ocean, she knew, Dr. Carter was an old man now, if he was still alive. They had exchanged letters for years, then less frequently as their lives grew fuller. The flow of paper had finally stopped a few years back, after his last note apologizing for his shaking hand and tired eyes.

If he could see this, she thought, he would smile that same crooked smile and say, “I told you so.”

She remembered the night he had griped about bureaucrats and supply lists, back when everything was still fragile and nothing was guaranteed.

“Do you ever feel,” he had asked her then, “like we’re just putting bandages on a world that insists on falling apart?”

She had answered, even back then, with a quiet certainty that surprised her.

“Maybe,” she had said. “But someone has to hold the pieces together while the world remembers how to heal.”

Now, standing on a street that had once been rubble, watching students of a school that had once been an idea in a borrowed room, she felt that same certainty deepen.

The world would never stop needing nurses. Illness would not politely wait for better times. Fear would not schedule itself around politics or economics. But as long as someone was willing to show up with calm hands and a steady voice, there would be hope.

She walked the rest of the way home, passing the church where the relief kitchen had once handed out bowls of watery soup. It was peaceful now, its doors open for quiet prayer instead of hungry crowds. She could still see herself in the doorway—thin, frightened, trying to be strong for others, body betraying her without warning.

If that young woman could see this older version of herself, cane in hand, back straight, she would be stunned.

You did not just go back to work, the girl would think. You turned your illness into a road that others could walk.

At her small apartment, Elise lit a lamp and sat at her desk. From the top drawer, she pulled out an old photograph: a slightly faded image of a younger her standing on crutches beside Dr. Daniel Carter in front of the first nursing classroom. They both looked tired. They both looked stubborn. Behind them, the borrowed room’s door was open, showing a single bed, a single chalkboard, and a world of possibility.

She traced the edges of the photograph with a fingertip.

“Thank you,” she said quietly—to him, to her past self, to every person who had refused to let her give up on that winter night so long ago.

The next week, at the ceremony, she stood in front of the building that now bore her name: ELISE BAUER SCHOOL OF NURSING.

Students and faculty gathered, along with local officials and a few older citizens who remembered the town as it had been. The hospital director gave a speech full of numbers and achievements. Miriam spoke about Elise’s kindness and firm standards.

When it was Elise’s turn, she stepped up to the small podium, her hand resting lightly on the smooth wood.

“I did not do this alone,” she began. “I could not have.”

She told them, briefly, about the cold night she collapsed in a supply closet, about waking to an unfamiliar ceiling and an unfamiliar voice speaking her language with a strange accent.

“A doctor who was not from here saved my life,” she said. “He did more than repair my body. He insisted that my story did not end with that illness. He told me I could still serve others. And then he challenged me to teach.”

She looked at the rows of faces: some young, some not. Some eager, some serious.

“I made a promise to myself then,” she continued. “If I was allowed to stand again, I would not spend that gift only on myself. I would pass it on. To as many people as I could.”

She gestured toward the school behind her.

“This building is not about me,” she said. “It is about promises kept. It is about the idea that one act of care—one doctor choosing to fight for a frightened young nurse instead of simply moving on to the next patient—can ripple outward farther than anyone expects.”

She paused, letting the quiet settle.

“Each of you who studies or teaches here,” she said, “is part of that ripple. You will go places I never will. You will comfort people I will never meet. Some of you will train others, and they will train others, and long after all of us are gone, there will be hands that know how to heal because of what you do.”

She smiled, the faint asymmetry of her face now simply part of who she was, not a flaw.

“So today, when you see my name on this building, don’t think of one woman surviving an illness,” she said. “Think of a chain of kindness stretching across borders and decades. Think of an American doctor in a tired uniform, telling a frightened young nurse that her life was not over. Think of the ten thousand nurses who have studied here. And think of the thousands more who will follow.”

She rested her hand briefly on the podium.

“Take the care you receive,” she finished, “and turn it into care you give. That is how we honor those who helped us. That is how we say thank you.”

Later, as people mingled and congratulated her, a young student approached. She wore the school’s current uniform and clutched her notebook to her chest.

“Frau Bauer?” the girl asked shyly. “May I ask you something?”

“Of course,” Elise said.

“What should I do,” the student asked, “on the days when it all feels too heavy? When I am tired, and the ward is full, and I am afraid I will not be enough?”

Elise took the girl’s hand, just as she had taken so many hands over the years.

“On those days,” she said softly, “remember you are not alone. Remember there were nurses before you, standing in more difficult conditions with fewer tools. Remember there are nurses beside you now, even if you cannot see them in the moment. And remember that being ‘enough’ does not mean fixing everything. It means showing up. It means doing the next right thing with as much kindness as you can.”

The girl nodded, eyes bright.

“And if that is still not enough?” she asked.

Elise smiled.

“Then you come back here,” she said, “and you let someone take care of you for a while. Even nurses need nurses.”

The student laughed through her tears.

As the sun dipped lower, casting warm light across the building’s facade, Elise felt a quiet peace settle over her. The promise she had whispered in the dark so many years ago had grown into something far larger than she could have imagined.

She had been saved by an American doctor on a winter night when everything seemed to be falling apart. She had gone on not only to return to nursing, but to train more than ten thousand others.

In the end, her story was not about illness or borders or even about numbers.

It was about what happens when one person refuses to let another person’s story end too soon.

It was about the way a single act of belief can echo through generations, changing the face of care in a thousand quiet rooms where no one is taking pictures, but everything important is happening.

And it was about the simple, stubborn truth that as long as there were hands willing to hold and hearts willing to listen, the world—no matter how broken—would always have a chance to heal.

THE END

News

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

The Hour That Shook Two Nations

After watching a mysterious 60-minute demonstration that left him speechless, Churchill traveled to America—where a single unexpected statement he delivered…

The General Who Woke in the Wrong World

Rescued by American doctors after a near-fatal collapse, a German general awakens in an unexpected place—only to witness secrets, alliances,…

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning—but instead uncovered a web of astonishing D-Day preparations so elaborate, bold,…

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline. The Fake Takedown Video That Fooled Viewers, Enraged Comment

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline….

“I THOUGHT RACHEL WAS FEARLESS ON AIR — UNTIL I SAW HER CHANGE A DIAPER”: THE PRIVATE BABY MOMENT THAT BROKE LAWRENCE O’DONNELL’S TOUGH-GUY IMAGE. THE SOFT-WHISPERED

“I THOUGHT RACHEL WAS FEARLESS ON AIR — UNTIL I SAW HER CHANGE A DIAPER”: THE PRIVATE BABY MOMENT THAT…

End of content

No more pages to load