My neighbor publicly humiliated me for years — mocking my job, my clothes, my car — so I stayed quiet, built an unexpected life from the scraps, and one autumn evening I walked back in with proof she would never mock again.

I learned two things early on: silence can be its own kind of armor, and small kindnesses add up into something that looks, from the outside, a lot like luck.

Her name was Marianne, and she had a laugh like a headline — loud, sharp, able to cut through a room and land on whoever she had decided was the evening’s entertainment. We were neighbors on a narrow street of identical townhouses, the kind of place where everyone knew everyone else’s business and the echo of a story grew faster than the truth. Marianne ran a PTA, hosted book-club brunches, and graded everyone in terms of who belonged and who didn’t. I fell into the latter column early: I had a job in a small nonprofit, a reliable secondhand Civic, and a habit of buying my clothes at the thrift shop down on Fifth. To Marianne, thrift store fashion was a character defect.

She humiliated me in public, of course. The cocktail party at the community center where she announced, with a clink of her glass, that “some people simply don’t know how to present themselves.” The playground coffee mornings where she commented on my daughter’s “quirky” lunchbox like it was an instructive anecdote. The garage sale — my own — where she loudly wondered why I didn’t “up my standards” before anyone else had the chance.

There were private barbs too. Notes slipped under my door about “neatness” and “standards.” A forwarded email to half the block with a photo of my curtains next to a mocking caption. Once, she left a stack of glossy magazine pages on my porch — each with pictures of the “right” kind of life — and a Post-it that read, just some inspiration.

For a long time I tried to meet her in the arena she’d chosen. I laughed when she laughed. I tried being clever in return. I reminded myself she was insecure, bored, performing. None of it mattered. She liked the show. The audience mattered more. So I stopped performing.

Instead I worked.

My job paid modestly, but it gave me a steady rhythm: early mornings of emails and late nights of grant proposals. Between that and picking up freelance editing, I put away small sums. I learned to cook fewer expensive meals and more soups and stews that lasted. I learned to take the bus when my car needed a week’s work. Every dollar I didn’t spend on being somebody else went into a folder labeled options.

Marianne doubled down on her life of appearances. When she wanted a promotion at the real estate office, she celebrated with an expensive bag and a post everyone clucked over. She took classes — etiquette, hosting, “strategic networking” — and wore her triumphs like medals. She’d parade her victories in front of the neighborhood like a banner. People admired her. People imitated her.

Meanwhile, I opened the folder sometimes and imagined what “options” could become. A class, perhaps. A trip that was really a conference in disguise. A seed fund for the small idea I’d been nurturing: a downtown shared workspace for neighborhood artists and organizers, an affordable place where local craft and community projects could find room to breathe. The seed idea was half-formed; I spent late nights sketching a plan between dinner and sleep.

What Marianne didn’t see then — because she didn’t look past performance — was how persistently small changes add up. I found a cheap lease on a corner unit a few blocks over that used to be a cobbler. The landlord wanted a reliable tenant who’d take care of the gutters; we met over coffee and signed the lease with a polite handshake. I sent that initial options money in cheerful wire transfers and payed the deposit with hands that trembled a little. I painted the place myself with volunteers from my nonprofit and neighbors who liked the idea of a community hub. People brought mismatched chairs and secondhand lamps. We held potlucks. We made lists. We wrote mission statements at midnight.

When we opened — half-excited, half-terrified — the neighbors came. Some because curiosity is a civic duty, some because the idea of something for “us” sounded better than another boutique selling things named after mountains. My daughter cut a ribbon. We celebrated like it was our anniversary.

It wasn’t a catapult to instant success. We weren’t a buzzword on morning TV. We were a place where kids learned clay, where an elderly neighbor taught bookbinding, where a young couple could rehearse their first open-mic set without a cover charge. We had a modest membership, a small calendar of workshops, and a bank account that was slowly inching upward. The community began to use the space in ways I hadn’t imagined: a tutoring club blossomed on Tuesday nights, a monthly swap event replaced the seasonal garage-sale mania, and a local maker’s market drew small, proud crowds.

Meanwhile Marianne continued her parade of curated moments. She came to two events at the workspace because she wanted to “see the competition.” She observed, scribbled notes, and left a review that, at first glance, sounded measured: “Interesting concept. Could use refinement.” She meant it as a rebuke. People saw it as constructive commentary. She tried to perform the same superiority in front of our small patrons, and the effect was the opposite: people respected someone who hadn’t left their neighborhood and built something, even if it was small. She had a lot of show, but we had something quieter and sticky: people who returned.

I want to be clear that none of this was about revenge. I never plotted a public downfall, never sought to humiliate Marianne the way she had humiliated me. What I wanted — selfishly and fiercely — was dignity. I wanted a life that was not at anyone’s mercy. I wanted to answer to my own sense of what mattered. If Marianne’s commentary stopped being the loudest thing in the room as a result, that was a consequence I would accept.

The turning point came on an unremarkable Wednesday. We were hosting a community fair at the workspace — a day of workshops, handmade goods, and a potluck that overflowed onto the sidewalk. A local council member came by to speak about neighborhood zoning. A small article was posted in the city paper, modest but precise. The next morning, one of my volunteers sent me a message: the paper’s story mentioned our project as a model for low-cost neighborhood revival. Someone with the city’s development office had noticed. A small grant — the kind that pays for heat and a better coffee machine — had been earmarked for us.

I still remember stepping outside and seeing Marianne across the street with her neighbor friends, clutching a glossy brochure from a competing development office. Her smile was practiced; her posture was perfect. She crossed the street as if our success were merely an errant cloud that had drifted over her lawn. As she drew near, her voice had the casual acidity of a vine.

“Your little club got some press,” she said, loud enough for her group to hears. “Cute. I suppose anything goes these days.”

I felt the old twinge of fear — but it had new company: a quiet, unflappable steadiness. I looked at her and answered, without theatrics, “We did. People came together. That seemed to be the point.”

Her smile curdled. “Well, I hope you can keep up with the bureaucracy. Grants are complicated. Not everyone is cut out for it.”

I could have said many things. I could have told her about the nights my daughter slept through the hum of the heatless winter, about the careful spreadsheets and volunteers and the city liaison who had folded his hands together and said, “This is what a neighborhood bureau should look like.” Instead, I walked across the street to her porch — slow, deliberate steps — and I rang her bell.

She opened the door. The neighborhood watched, because that’s what neighborhoods do. A quiet crowd assembled like weather.

“Hi, Marianne,” I said. “Do you have a moment?”

Her hand hovered, mid-gesture, like a bird deciding whether to flee. “Of course,” she said, voice clipped. “What is this about?”

I smiled. “I wanted to invite you to a meeting. We have a workshop tomorrow about zoning and small grants. I thought you might like to see how it works. We need community leaders — people who care.”

She looked like a fish who’d been offered a stream. There was an awkward pulse of pride — she loved anything that placed her center-stage. This was a bait she would take, I thought, but that thought was uncharitable, and I couldn’t care. She accepted.

The next day she came. She asked questions — performative at first, sharp and loud — and the city official, who had once been a bureaucrat’s dream and now warmed to practical action, listened. He answered. Marianne found herself on a panel, requested by the audience, asked to explain zoning law to a room of neighbors. She performed admirably: rehearsed phrases, emphatic hand gestures, a polished voice.

When the session ended, people lingered. The councilman turned to Marianne and said something I never expected: “Your remarks were clear. If you’d like to work with us, we’d be grateful for your help vetting local proposals.”

Marianne’s face, for a moment, was open and raw. The applause was real. She beamed. But it had a new quality — not derision, but real warmth from the room. A few people leaned in with questions, not to test her but to ask her to stay. At the reception afterward she was surrounded by neighbors who wanted to partner, to volunteer, to learn.

It struck me then that the worst of Marianne had always been a performance, a cover for not knowing how to belong. That day she stepped into the very work she’d mocked and was met with a community that wanted help not criticism. She was humbled — in a good way — and I felt no glee at the sight. Just relief.

Time did the rest. The workspace grew slowly into a living room for our block: a place where hummus and careful workshops and earnest debates about potholes could happen on the same day. Marianne started to volunteer on the registry board. She learned how to write grants. She learned what it meant to listen instead of rate. People forgave her small cruelties not because they forgot them but because they saw effort. She softened. Her laughter still carried, but it carried something else now: inclusion.

A few months later she stopped by my door with two cups of coffee — paper, because she’d learned our neighborhood preferred local roasters to boutique displays. “I’m sorry,” she said, clumsy and sincere. “I was wrong. I haven’t been kind. You’ve done good work.”

Her apology was not a public spectacle. It was neither the toppled throne nor the dramatic reveal many stories require. It was, instead, the beginning of the work: she showed up, she helped, she listened. We built a potting bench together one Saturday, and she told the kids the story of the weird plant she’d killed last year, and everyone laughed.

Humiliation had taken a long walk through my life. It could have been the last word. Instead it became a preface — the reason I wanted a home not made from other people’s approval, but from the quiet architecture of doing useful things. I didn’t make Marianne bow. I didn’t need to. What I did was simpler, and harder: I kept working until the space I’d made could hold us both. That, in itself, changed the tone of things. People stopped listening for glee and began listening for service.

If you ask me now which I’m most proud of — the grant, the ribbon-cutting, the quiet evenings with kids gossiping over cocoa — I’ll tell you the same thing: I am proud that a life can be reclaimed without breaking others. That sometimes the best answer to humiliation is to keep showing up to do something better. And that, eventually, people change when the work becomes more important than the applause.

News

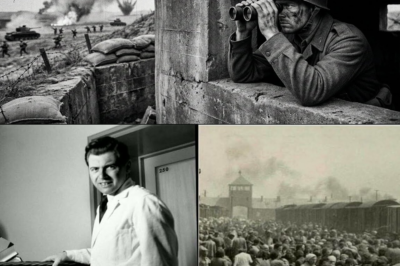

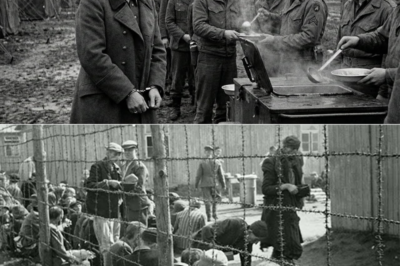

The Stunned Reactions Inside Germany’s High Command When Officers Realized Their Leader Had Brushed Aside Crucial Warnings Before D-Day — And How That Single Choice Triggered Shock, Denial, and Quiet Panic Behind Closed Doors

The Stunned Reactions Inside Germany’s High Command When Officers Realized Their Leader Had Brushed Aside Crucial Warnings Before D-Day —…

The Incredible Night When a Quiet U.S. Marine Used a Clever Machete Strategy to Protect His Surrounded Platoon, Outsmart Waves of Enemy Fighters, and Turn a Hopeless Jungle Standoff Into a Dawn of Survival and Brotherhood

The Incredible Night When a Quiet U.S. Marine Used a Clever Machete Strategy to Protect His Surrounded Platoon, Outsmart Waves…

The Incredible Tale of One Wounded American Soldier Who Outsmarted an Enemy Patrol With Nothing but Nerve, Grit, and a Clever “Possum Trick” — Surviving Five Wounds to Defeat Six Opponents and Capture Two More

The Incredible Tale of One Wounded American Soldier Who Outsmarted an Enemy Patrol With Nothing but Nerve, Grit, and a…

The Moment a German Observer Looked Across the Horizon, Counted More Than Seven Thousand Allied Ships, and Realized in a Single Shattering Instant That the War He Had Believed Winnable Was Already Lost Beyond All Doubt

The Moment a German Observer Looked Across the Horizon, Counted More Than Seven Thousand Allied Ships, and Realized in a…

How Months Inside an Unexpectedly Humane American POW Camp Transformed a Hardened German Colonel Into a Tireless Advocate for Human Dignity, Justice, and Liberty — And Sparked a Lifelong Mission He Never Saw Coming

How Months Inside an Unexpectedly Humane American POW Camp Transformed a Hardened German Colonel Into a Tireless Advocate for Human…

How a Calm Conversation Between an African-American Sergeant and a Captured German Soldier Shattered a Lifetime of Misguided Beliefs and Transformed a Winter Prison Camp into a Place of Unexpected Understanding and Human Connection

How a Calm Conversation Between an African-American Sergeant and a Captured German Soldier Shattered a Lifetime of Misguided Beliefs and…

End of content

No more pages to load