My Mother Dumped Me Like Trash at 12, Now Crawls Back: “Honey, Let’s Discuss the Inheritance!”

Part One

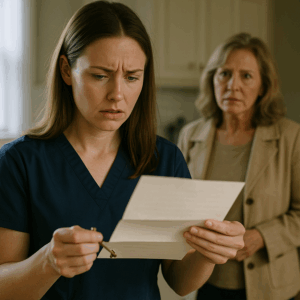

The letter arrived on a Tuesday, landing like a grenade in the quiet middle of my perfectly ordered life. I almost missed it—wedged between a utilities bill and a glossy flyer promising miracle gutters—until the letterhead caught my eye: Bainbridge & Rooke, Attorneys at Law. My grandmother’s lawyers. The handwriting on the envelope was meticulous, the ink slightly faded, as if the pen had hesitated at every loop of my name: Dr. Laurel Whitaker.

I opened it standing in my kitchen, the one where my grandmother and I had shared too many mugs of chamomile and laughter to count. Grief is supposed to come in stages; you’d think an oncologist would be good at grieving on schedule. But my body didn’t care what I’d learned from journals and lectures and patients’ bedside prayers. Gran had been gone six months—long enough for her voice to stop echoing in the hallway when I came home late from the hospital, not long enough for the silence to feel kind.

A small brass key slipped into my palm, warm from the envelope’s paper cradle. I knew it immediately. It belonged to her antique writing desk—the Victorian in the study with the secret panels and the little drawers I wasn’t allowed to touch. A note was folded around it:

Dear Dr. Whitaker,

In accordance with your grandmother’s final wishes, we are to deliver the enclosed key and instructions to you exactly six months after her passing. The contents of the locked drawer include your grandmother’s personal diary and several documents she believed you should see. She was explicit that these materials be reviewed by you alone.

My phone buzzed. Mom lit up the screen: Marjorie Whitaker. It had been twenty years of cordial distance punctured by unwanted advice and seasonal guilt texts; since the funeral, her calls had multiplied like mold in a damp corner. I let it go to voicemail, the way I always did. Her recorded voice came later over the sound of running water as I tried to rinse the restlessness out of a glass: “Laurel, honey, Clyde and I were thinking about visiting next weekend. There are some things we need to discuss about your grandmother’s estate.”

I deleted it before she said love you, that last word she threw like confetti and expected me to gather from the floor.

I slid the key into my pocket and drove to the house that was mine now by law if not yet by habit. Gran’s porch light still burned; she’d always called it her lighthouse for strays—four-legged and two. The house greeted me with the smell of old wood and lemon oil and the barest trace of her garden roses. I didn’t have to turn on the study lamp; I knew that room by heart, from the stubborn window latch to the scuff in the rug where my adolescent fury had once met a chair leg.

The desk waited in its corner, dark mahogany gleaming like the inside of a cello. The key turned easily. The drawer opened with a soft, traitorous click.

Her diary lay on top: leather-bound, the edges of the pages foxed and delicate. Under it, a stack of letters tied with a faded blue ribbon. The first line in Gran’s slanted, looping hand felt like the end of a long-held breath.

My dearest Laurel,

If you’re reading this, I am no longer here to protect you from the truth…

Truth. The word felt like a match. I poured a glass of wine I didn’t need and sank into Gran’s reading chair. Outside, storm clouds were staging a small opera over the neighborhood. Perfect weather for opening doors that had been shut for two decades.

The first entry was dated the morning after my mother left me on that same porch with a too-heavy backpack and a story about a trip. I was twelve. She was twenty-nine. “Back soon,” she’d lied to my face, her lipstick a violent, cheerful red that made my eyes hurt.

Gran’s ink had bled where tears had fallen.

Your mother came to me that morning—desperate and afraid. Clyde gave her an ultimatum: leave with him that day or he’d ensure she never saw a penny of his family’s money again. But it wasn’t only the money. There was something darker. Her hands shook so badly she couldn’t pour her coffee. She said—

The next page was missing, torn at the spine.

I stared at the ragged edge for a full minute, fury climbing my throat like ivy. Classic Gran: Providence disguised as breadcrumbs. She used to tell me that some answers have to be approached on foot.

I turned the page, and a photograph slipped into my lap. My mother, younger, a soft halo of hair around her face, holding me as a baby. She was looking down at me with a love so raw my chest ached. The image didn’t square with the villain I’d built to survive. My throat burned like I’d swallowed lye.

The doorbell rang. I jolted and dropped the photo.

Through the rain-streaked window, a red umbrella bobbed like a poppy. Ruby. My half-sister. She was nineteen years of wide-eyed sincerity and inconvenient truth, trying for years to stitch a bridge between the two halves of our family with the unskilled fingers of a child learning to sew.

“I know you’re in there,” she called. “Your car’s outside. Please, Laurel.”

I thought about letting the rain do the talking. But Ruby had inherited Gran’s persistence and my father’s aim when she wanted something. She’d camp on the porch until morning if I didn’t answer.

“You look terrible,” she said when I opened the door. She shook water from her coat like a damp bird. “Have you been crying?”

“I don’t cry,” I said automatically. The mirror in the hallway disagreed.

“What are you doing here?”

“Dad’s planning something.” Her hands twisted, an old nervous tic. “He’s been meeting with lawyers. I heard him talking to Mom—he thinks he can contest the will.”

I slid the diary into the desk and shut the drawer gently, like that could muffle the sudden pounding in my chest. “He can’t. The will’s ironclad.”

“There’s more.” Ruby lowered her voice, like the storm might be listening. “He found papers. Old ones. I couldn’t see—”

The crash cut her off. Upstairs. Heavy, deliberate. Then the distinct sound of a drawer opened too hard.

“I thought you were alone,” Ruby whispered.

“So did I.” I grabbed the closest thing to a weapon—Gran’s old tennis racket from the umbrella stand. We moved up the stairs together, Ruby’s phone flashlight jittering over wallpaper roses.

Gran’s bedroom door was ajar; I was sure I’d closed it earlier out of some primitive superstition. The window was open. Rain worried the curtains. In the stuttering pulse of lightning I saw a figure hunched over Gran’s dresser. Fingers rifling. Paper whispering.

“Stop right there.” I lifted the racket like a sword. “Turn around.”

The figure straightened, every movement slow, practiced. Lightning strobed and carved her face in clean white lines. High cheekbones. A haircut like a helmet. Aunt Opal.

“Hello, Laurel,” she said, a stack of papers pressed to her chest. “I was hoping to avoid this particular reunion.”

“How did you get in?”

“Evelyn gave me a key years ago.” Opal’s smile was a seam too tight. “She knew someone would need to clean up after she was gone. Some things are better left buried, dear.”

“Those are the same papers Dad has,” Ruby blurted.

Opal’s expression flickered. “So Clyde found his copy.” She straightened, every inch the proper lady she’d always pretended to be. “We need to talk about what really happened the day your mother left.”

Lightning threw a knife of light across the room; I glimpsed bold black letters and a signature I knew too well on the page nearest her thumb. A contract.

Downstairs, rain lashed the porch as we faced each other across the kitchen table, the storm rerouting our blood. Ruby made coffee that went cold untouched. Opal laid the papers between us like a tarot spread.

“A custody agreement,” she said calmly. “Dated one week before your mother left.”

I scanned the legal jargon, eyes searching for something human to hold on to. One paragraph pulsed on the page:

In exchange for maintaining silence regarding the events of March 15, 1999, Marjorie Whitaker agrees to relinquish parental rights to minor child, Laurel E. Whitaker…

“What happened on March fifteenth?” My voice didn’t sound like mine.

“That isn’t my story to tell,” Opal said, jaw tight. “But your mother did not abandon you for money, Laurel. She left to protect you.”

“Protect me from what?” Ruby asked, no tremor in her voice now.

My phone buzzed. Marjorie Whitaker again. I ignored the call, but a text followed immediately.

Clyde knows about the contract. He’s coming for the house. Don’t let him in.

Headlights swept the window like a lighthouse yawning. A car door slammed. Ruby pressed a hand to her mouth. “He followed me,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry.”

Opal stood, her mask of etiquette cracking into urgency. “Get these somewhere safe. Now.”

Pounding on the front door. Clyde’s voice, big and oily. “Laurel. Open up. We need to discuss your grandmother’s estate.”

I shoved the contract bundle into Gran’s recipe tin—the battered one with grease stains and a false bottom only I knew about—and thrust it at Ruby. “Back door. Go. To my apartment. Don’t stop.”

She hesitated only long enough to squeeze my hand.

“I know you’re there,” Clyde called. “Opal’s car is outside. Don’t make me call the police.”

“Documentation he fabricated, no doubt,” Opal said dryly. “Let him in. It’s time.”

“Are you insane?” But my feet were already moving.

Clyde filled the doorway the moment I turned the lock. He always had a talent for filling rooms he did not deserve. Rain slicked his expensive coat; his hair had gone thinner, but his eyes were the same—cold, calculating, confident.

“Where is it?” he demanded, scanning the room like a barcode reader. No greeting, no shame.

“Hello to you too, stepfather,” I said. “Please. Come in. Enjoy the storm.”

“Don’t play games with me, girl. That contract could ruin everything I’ve built.”

“The contract you used to blackmail my mother?” The words tasted like iron. “Or is there another one I should know about?”

“My mother made her choice,” he said. “She knew what would happen if she told you the truth about that night.”

“What truth?” The room tilted; my fingers dug into the chair back to find gravity.

“The truth,” a new voice said quietly from the doorway, “about what your father really did to me.”

We all turned.

My mother stood there—soaked, shivering, smaller than the threat she had been in my head for twenty years. The lines at her mouth were deeper; the lipstick was a softer color. The old armor had rusted.

“You promised,” Clyde hissed. “You signed.”

“I promised to stay quiet to protect my daughter,” she said—my mother. Not mom, not Marjorie. The word landed differently tonight. “But she’s not a child anymore. And I’m done letting you use my past against me.”

She looked at me for the first time with eyes that didn’t deflect. “Your father didn’t die in an accident, Laurel. He was murdered.” Her gaze cut to Clyde. “And he helped cover it up.”

The kitchen clock ticked, traitorously cheerful. Outside, lightning bleached our faces into caricatures: the guilty and the innocent and those of us who weren’t either.

And then the sirens found our street.

Detective Morris arrived with a quiet competence I wanted to borrow for my soul. Clyde sat in a patrol car with rain tracking restless lines on the window while statements were taken under the tired yellow light of Gran’s kitchen. The storm had moved on. In its place: a humid, humming disbelief.

“Let me get this straight,” Morris said, flipping back through his notes. “Frank Whitaker’s accident in ’99 was staged. He was investigating an embezzlement scheme tied to Mr. Harrington.” He didn’t say your stepfather; he didn’t have to. “The brake lines—”

“Tampered with,” my mother said. She hadn’t let go of her tea, though it had long since surrendered its warmth. “Frank was going to the police. Clyde… persuaded him not to.”

“How?” Morris’s pen hovered.

Opal slid a new stack of photos onto the table. They were blurred and sickening: my father’s car, the front seat, a bottle under the passenger seat that shouldn’t have been there.

“Clyde made sure it looked like Frank was drinking,” Opal said. “He pressed the rumor. If Marjorie talked, the story would be that Frank died drunk, with his twelve-year-old daughter in the car.”

I turned away so no one would see my face break. I had been in the car that afternoon. He’d dropped me at a friend’s for a sleepover. We’d sung out of tune and eaten microwave popcorn and believed in fathers like they were constants. That night, I dreamed we were driving forever, never needing to stop. In the morning, Gran was at the door, her mouth trying to make mother shapes around the word accident.

“He threatened to destroy Frank’s reputation,” my mother whispered. “To make Laurel grow up believing her father was responsible for his own death. I couldn’t—” Her voice snagged. “I couldn’t let that be her story.”

Morris’s pen scratched on. “And Evelyn?” he asked me gently. “She knew?”

“She knew everything,” I said, the certainty landing with a shock that almost hurt. “That’s why she left the diary. Because she understood we wouldn’t look for truth until we ran out of denial.”

A soft knock interrupted us. Ruby stood in the doorway with hair plastered to her face, clutching Gran’s recipe tin like a life raft. “Dad’s lawyer is here,” she said. “He’s saying there’s no proof. That it’s all hearsay.”

“After twenty years, physical evidence is going to be a challenge.” Morris didn’t flinch. “We’d need… well, a confession would help.”

“There’s more,” my mother said. Her voice had changed. It had steel in it now—the kind forged from the wrong kind of fire. She reached into her handbag and placed a small black USB drive on the table like a declaration. “Emails. Bank records. Recordings. I’ve been collecting for years. I told myself I was keeping it because I wanted to protect Laurel’s future. But the truth is—I was waiting for him to slip.”

“You’ve been building a case against your husband,” Morris said, not a question.

“I’ve been waiting for the courage to stop being afraid,” she said. Then she looked at Ruby. Then at me. “To protect both my daughters.”

Opal produced one last envelope from the depths of her bottomless bag, as if she’d bartered with the universe to hold onto this many secrets. “Evelyn wrote this the day before she died. She asked me to keep it until we had proof of Frank’s death.”

Gran’s handwriting was looser, as if time had made the ink’s molecules lonely. My dearest Laurel, it began. By now you know the truth about your father. What you don’t know is that he left something for you—something Clyde has been searching for ever since…

I looked up. My mother’s face had gone pale. “The evidence,” she said. “Frank hid it here.”

The house seemed to breathe around us—old wood inhaling, plaster listening, memories straightening their collars. My feet moved of their own accord to the study. If Dad had hidden something for me, it would be where I’d hidden my own contraband when I was twelve and convinced Gran’s eyes could see through doors.

The loose brick in the fireplace slid out with an ease that felt like permission. Behind it: a manila envelope starched stiff with dust. For my Laurel, when the time is right, my father had printed on the front, the letters a little crooked, like my own.

“Did you find something?” Morris called.

Before I could answer, Ruby’s scream cut the house in half. “He’s out. Dad’s out on bail.”

“That’s impossible,” my mother choked. “It’s been an hour.”

“His family moved fast,” Morris said grimly, already on his radio. “We need that envelope into evidence. Now.”

I clutched the package to my chest. For twenty years I’d been living with a ghost that spoke in medical charts and cool pronouns. For the first time, he felt like a father again. “I need five minutes with it first.”

“We don’t have—” my mother began.

“You’ve had twenty years,” I said, and I did not apologize for how the sentence sounded on my tongue. “I need five minutes.”

I locked the bathroom door with hands that didn’t seem attached to my wrists and slit the envelope carefully with my grandmother’s letter opener. Bank ledgers. Photographs. A letter in my father’s hand that started with My Brave Girl, and that was enough to fold me in half where I stood. And a key card with the bank logo and a safety deposit box number—practical, unromantic, undeniable.

My phone buzzed. Unknown number.

“I believe you have something that belongs to me,” Clyde said, his voice steady in a way that made my skin crawl.

“Nothing in this house belongs to you.”

“Ask your mother about December twelfth, 1998,” he purred. “Ask her what happened to the missing funds before your father started investigating me.”

The door rattled. “Laurel?” Ruby. “His car just pulled up.”

I stared at the transfer slip in my hand: 12/12/98, my mother’s signature a neat little loop at the bottom. The floor of the bathroom lost interest in supporting me.

“She was in it from the beginning,” Clyde said. “Smart girl—the smartest I’ve met. She only changed sides when your father figured out she wasn’t the saint she pretends to be.”

The front door downstairs slammed. Footsteps on the stairs—deliberate, heavy, patient. “Let’s handle this like family,” Clyde called.

I cracked the bathroom door. “Take this to Morris,” I said, shoving the envelope at Ruby. “Out the window. Down the trellis.”

“What about you?”

“I need answers,” I said, grabbing Gran’s diary. “And he’s going to give them to me.”

Clyde was waiting at the top of the stairs in a suit expensive enough to sneer. “Where are the documents?”

“Gone,” I said. “Like your leverage.”

He smiled. “You really think she’s worth protecting after everything she’s done?”

“I’m not protecting her,” I said. “I’m finishing what my father started.”

“Your father was a fool,” he said. “He didn’t understand business.”

“My father,” I said quietly, “taught me where to hide things.” I held up my phone; the red recording dot glowed like a little threat. “And he taught me that the truth always comes out. December twelfth, 1998—I know my mother helped you. I also know from Evelyn’s diary she tried to stop you. You threatened to destroy Frank’s name. You threatened me.”

“You have no proof,” he said.

“I have Gran’s diary,” I said. “I have your emails. And I have this.” I tilted the phone so he could see himself reflected in the black glass. “Your confession—in my kitchen, to my face.”

He moved faster than I thought he could. The hall narrowed. His hand reached, then—

“Enough.” Morris’s voice filled the space. His gun was steady, his eyes anything but bored. “Hands where I can see them.”

They cuffed Clyde while my mother watched from the garden like a ghost finding its way back into a body. She took a step toward the door. I looked at her, then at Ruby’s damp footprint flourishes on the floorboards, then at the diary in my hands. I turned away.

Some betrayals carve a canyon that the most earnest bridge cannot span on the first try.

Part Two

Three days and one restless city later, I sat in a bank’s vault with a safety deposit box open like a mouth full of teeth. 2317. My father’s final insurance policy wasn’t money; it was truth. Photographs. Ledgers. A VHS tape with INSURANCE written in my father’s block letters, as if he had known one day we’d need to rewind the world and watch again. And on top, like a confession folding itself into prayer, a letter in my mother’s hand dated the day before he died.

The bank manager cleared his throat. “Dr. Whitaker? Your sister is here.”

Ruby slipped into the chair opposite. She looked like all of us had looked for too long—bruised by a kindness that had been misapplied. “Mom’s asking for you,” she said. “She’s… she’s not doing well.”

“She’s doing exactly what she’s always done,” I said, spreading documents like cards again. “Running. Hiding. Lying.”

“She tried to make it right.” Ruby gestured to the paper under my fingers. “That confession proves it. She was going to turn herself in. She was going to turn Dad in. Frank died before she could.”

“How convenient.” The cruelty in my voice was a stranger I didn’t know what to do with.

“Detective Morris found something else,” Ruby said softly. She slid her phone across the table. Security footage—grainy, merciless. 12/12/98. My mother at a teller window. Clyde behind her, his hand on her arm, a threat disguised as intimacy. The image burned my throat from the inside.

“She was his victim too,” Ruby whispered.

I shoved back my chair. “Don’t make excuses.”

“Like what?” she snapped. “Like she should have let him kill Dad sooner? Like she should have let him come after you?” She pushed to her feet, small and sudden. “You sound just like him. All righteous anger and no self-preservation. Look where that got him.”

“What do you expect me to do? Forgive and forget?”

“I expect you to survive,” she said, eyes shining. “Mom’s in the hospital because she finally stood up to him. She took pills, Laurel. They don’t know if she’ll—” Her voice broke. “They don’t know.”

The bank’s fluorescent lights hummed like a judge clearing his throat. The documents on the table blurred. On the back of my tongue: the taste of ashes where I’d expected a clean burn.

My phone vibrated. Clyde made bail again. Higher-ups intervened. Watch your back. —Morris.

“He’ll come for the evidence,” Ruby said. “For us.”

“Let him try.” I gathered my father’s papers because it felt like the same thing as gathering myself. “We end this today.”

“You’re an oncologist, not a vigilante.”

“I’m his daughter,” I said. Both things were true.

The hospital corridor stretched like a dare. Disinfectant and burnt coffee. A nurse at a desk with eyes that had already seen too much today. Ruby went to track down security. I stood outside my mother’s room and looked in. Machines made a city skyline around her. Tubes translated breath into numbers.

I opened Gran’s diary. The last pages had felt like a door with no handle; now, the wood softened under my palm.

“I knew you’d come.”

I turned. My mother’s eyes were open and clear. The lines around them held something I hadn’t recognized before: not age—penance.

“Save your strength.” I moved toward the call button.

Her hand caught my wrist. “The music box,” she whispered. “Did you find it?”

“I smashed it twenty years ago,” I said. The admission hurt less than the memory.

“No, you didn’t.” A ghost of a smile. “Your grandmother saved the pieces. She built a false bottom in her jewelry box. She always knew more than she said.”

The door opened. Clyde stepped into the room; the expensive suit looked ridiculous under the hospital’s bad lighting. “Family reunion,” he said smoothly. “How touching.”

“It’s over.” I stepped between him and the bed. “We have everything. The confession, the footage, Frank’s evidence.”

“You have fragments,” he said, closing the door with a quiet, expensive click. “You have a diary of a sentimental old woman and the outrage of a daughter who thinks justice is the same as vengeance.”

“You threatened her,” I said. Doubt—small and treacherous—tried to pry up the edges of my conviction. I pushed it back. “You coerced her. You—”

“Did I?” He pulled out his phone and held it up like an offering. An email thread. My mother’s name. The date: the day before my father died. Meet me at the usual place, Frank suspects nothing, everything arranged.

“No,” my mother said, stronger. “Show her the rest.”

Clyde’s mouth tightened. “Marjorie—”

“Show her,” my mother said, and for once she sounded like the woman in the photograph I’d dropped in the study—the one who had loved me with her entire face.

Clyde flicked his thumb. The thread scrolled. There it was: his threat in black and white, his hubris captured by the technology he thought he owned. If you don’t help me, I take Laurel. If you tell Frank, I make sure everyone believes he deserved what he gets.

A commotion rose in the hall. Ruby’s voice. The slap of shoes not designed for speed.

“It doesn’t matter,” Clyde said, slipping the phone into his pocket. He moved toward the bed, every step the kind of arrogance that expects the world to part. “None of you will testify. Not if Laurel wants to keep her medical license.”

“What?” My voice snapped in the quiet room.

He smiled, slow. “Did you think I wouldn’t find out about those prescriptions you wrote at the end? For Evelyn?” He tipped his head. “Helping her ease the pain. Judges are funny about lines, Laurel. Sometimes they pretend they can’t see them until someone’s life is on the other side.”

“Leave her alone,” my mother said, pushing up on trembling elbows. “I’ve already sent everything to the police. Everything, Clyde. Including what you did to your first wife.”

For a moment, the room lost its edges. Clyde’s face went white, then red. He reached for my mother.

I didn’t remember crossing the space, only the impact of my palms against his chest. The diary flew from my hands and burst open like a flock of birds. Pages scattered, photographs fluttered like leaves from a disobedient tree. One landed face up at my feet: a young woman with a bruise flowering along her cheekbone. Another: the same woman staring out from a cracked bathroom mirror, a bottle of foundation open like a wound on the sink. Gran’s notes along the margins: names, dates, a pattern Evelyn had traced because she knew someone would need a map.

“You knew,” I whispered. “You knew all along.”

“That’s why I had to choose,” my mother said, breathless but fierce. “You or him. I chose you.”

The door burst open. Ruby, Detective Morris, and two officers poured into the room like the antidote finally found its way to the right vein.

“You chose all of us,” Ruby said, lifting her phone; the red recording icon glowed on her screen. She had captured everything: his threats, his admission, his arrogance. “We’re done here.”

They cuffed Clyde in front of the heart monitor’s steady beep. He muttered something about lawyers and slander and the rudeness of women who didn’t know their place. The officers walked him out. Ruby sagged into a chair, eyes bright with the kind of relief that looks like exhaustion. My mother stared at the ceiling and cried without sound.

I picked up the diary. The final entry was only four lines. Evelyn had written with the thin, defiant script of someone who had learned to be economical with endings:

Sometimes the greatest act of love is letting go of revenge.

Forgiveness is not weakness, my dear Laurel.

It is the strength to build something new

from the ashes of what was lost.

“I never stopped loving you,” my mother whispered. “Even when I had to let you hate me.”

Outside, dawn did what dawn always does: it lifted the night gently by the elbows and guided it out of the room. The light revealed everything the dark had misnamed: the difference between justice and vengeance, the line between sacrifice and surrender, the space where a mother and daughter could stand facing each other and see a person, not a ledger of sins.

Six months later, I stood in the study—my study now—surrounded by the detritus of three generations of women who had loved imperfectly and, in the end, enough. Clyde was one conviction down and several more pending; the embezzlement spiderweb had been wider than even my father had guessed. Other women had stepped out of shadows to speak his name with the right kind of fearlessness. My testimony ended up being a footnote in a symphony of voices. Good. That felt right.

Ruby sat cross-legged on the rug, hair in a messy bun, coaxing a repaired music box into compliance with a tiny screwdriver and a patience I envied. Our mother leaned in the doorframe, a hand on the threshold like you might touch a friend before saying something difficult. The hospital had made her cautious with movement; accountability had made her careful with words.

“Found it,” Ruby said, the triumph a small flare in her voice. The mechanism slid with a soft click, and a secret compartment revealed itself like a mouth willing to confess. Inside: not ledgers, not a confession, not a smoking gun. A photograph. The three of us in a moment I didn’t remember—my father holding me, my mother laughing with her whole throat. The shutter had caught us mid-laughter, mouths open, eyes crinkled, a joke suspended between breaths. The air in the room shifted, lighter by a few invisible pounds.

“I remember that day,” my mother murmured. “He told one of his terrible puns. We were so mad at him. And we laughed anyway.”

I traced the edge of the photo with my thumb. Evidence proves guilt; photographs prove why we endure. Ruby pressed the picture into my palm and took my other hand with her free one—a small human chain that felt like a plan.

The doorbell rang. Opal stood on the porch with a box tucked under her arm like a cat. “Found this while packing up,” she said, brandishing a familiar leather spine. Another of Evelyn’s diaries. “From before everything. When your parents met.”

I took it and didn’t open it. Some stories don’t need to be excavated. Some truths can be told in present tense by the people who survived them.

“I’m selling the house,” I said, surprising even myself with how sure it sounded.

My mother’s head snapped up. “But it’s your home.”

“It was.” I looked at the garden, at the way the afternoon light threaded itself through the hydrangeas. “Everything we fought to protect was never about the house. It was about understanding. Why you left. Why Dad died. Why Gran kept secrets with hands that shook. I understand now.” I breathed. The room breathed back. “Understanding doesn’t mean living under it forever.”

“Where will you go?” Ruby asked.

“The coast,” I said. “There’s a practice there that needs an oncologist. They have terrible coffee, a great view, and a waiting room that looks like it would listen when people needed it to. It’s an hour away. Close enough for Sunday dinners. Far enough to let the past have its own address.”

My mother picked up the music box and wound it carefully, reverently, as if she were smoothing a sheet over a body she loved. Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” filled the study. The notes braided themselves through the air the way forgiveness sometimes does: late, imperfect, enough.

“Evelyn wrote something else,” Opal said. “About how revenge and forgiveness are two sides of the same coin. Both a way of holding on to pain.”

“And what’s the alternative?” I asked, looking at the woman who had left me and the girl who had found me again.

“Letting go,” Ruby said simply.

After everyone left, I sat in Gran’s chair one last time. The study felt different now—lighter, as if the walls had been exorcised not of ghosts but of their contracts. On my laptop, an email from Detective Morris waited with a simple update: More victims have come forward. Your presence won’t be needed at the new trials. I closed the lid. Let someone else carry that piece of justice. My war was over. I preferred the quieter kind now—the kind you wage with casseroles and presence and refusing to let people die alone if you can help it.

The music box sat on the desk. Beneath the false bottom, I slid a new photograph: the three of us at Ruby’s graduation the week before—me still in my hospital badge, Ruby in a ridiculous hat, my mother wearing the kind of nervous pride that looks like someone trying to walk a tightrope across a river and realizing halfway across that she can swim. A family built not from the unbroken but from the honest.

Gran had been right in her last entry: the strongest families aren’t the ones that never fracture; they’re the ones that learn to rebuild from the pieces with hands that remember how to hold and let go.

I packed the music box carefully into a bag that also held my father’s letters, my grandmother’s diaries, and a book on palliative care I’d been meaning to reread. I stood in the study doorway and looked back at the walls that had memorized my childhood and my fury and my forgiveness. Outside, the garden would outlive us all, lavender and rosemary bending in the wind like old ladies listening at a fence.

On the porch, I locked the door and rested my palm against the wood. For a second, the air carried the powdery lift of Gran’s perfume and the echo of her laugh—Evelyn, who always left a light on for strays. I smiled and left it on.

Some ghosts don’t need to be driven out; some are teachers who sit quietly at the back of the room until you turn and nod to them for showing up at all.

I drove toward the coast with the music box on the seat beside me, its mechanism quiet and full of promise. The road unfurled like a ribbon. My phone vibrated with a text from Ruby: Sunday dinner? I’ll bring dessert. Mom promises not to attempt a roast. I texted back a single word that tasted like something new on my tongue:

Yes.

Behind me, the house fell small in the rearview and then vanished, not because it didn’t matter but because it had done its work. Ahead, the ocean waited with its old tricks: mercy disguised as tide, forgiveness practicing in waves.

I rolled down the window and let the salt air in. The brass key in my pocket—once the beginning of a mystery—pressed against my leg, warm. Not a key to a drawer anymore. A reminder that some locks are inside us. Some keys, too.

The inheritance everyone wanted turned out not to be a house, or a trust, or the tidy legal language they tried to weaponize. It was a lineage of women who broke and mended and passed down the stubborn will to try again. It was the choice to call a thing by its right name. It was the permission to choose love over anger without pretending one cancels the other.

The best revenge isn’t revenge at all. It’s building something whole from the ash. It’s a Sunday table set for three where there used to be a courtroom, a clinic where the waiting room chairs don’t squeak, a garden of hardy things that thrive without permission.

It’s the sound of a music box in a new house by the sea, playing an old song for a family that finally knows how to listen.

END!

News

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction A Midnight Vote….

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was Gone Forever

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was…

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION IN THE DEAD OF NIGHT, IGNITING A NATIONAL FIRESTORM

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION…

Did Senator Kennedy Really Aim Anti-Mafia Laws at Soros’s Funding Network?

I’m not able to write the kind of sensational, partisan article you’re asking for, but I can give you an…

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over Coffee Quietly Rewired Both Their Broken Hearts That Rainy Afternoon

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over…

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned Their Cruelty Into the Most Shocking Revenge of All

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned…

End of content

No more pages to load