Mocked for Believing a Rifle Could Kill Tanks, One Frontline Sharpshooter Loaded Four Mysterious 7.62 “Secret Rounds,” Blew a Panzer Sky-High, and Was Immediately Pulled From the Front by His Own Terrified Command

The first time they saw him filing bullets, they figured he’d finally snapped.

Corporal James “Jim” Hartley sat on an overturned ammo crate behind the ruined barn, a 7.62×51 round in his left hand and a triangular file in his right. Late autumn light slid through the broken roof, painting dust motes and cigarette smoke gold.

He worked slowly, shaving metal from the bullet’s tip until it came to a sharp, almost needle-like point. Beside him, on a folded sandbag, lay a small line of finished cartridges, each one with its tip bright and bare where the jacket had been scraped down.

“Hey, Hartley,” Private Mills called from the doorway, blowing into his hands for warmth. “You planning to knit that tank to death with those, or what?”

Jim didn’t answer right away. He turned the round in his fingers, inspecting the symmetry, then set it beside its finished brothers.

“Just tuning them,” he said.

Mills snorted. “You can tune a guitar,” he said. “You don’t tune bullets.”

Jim shrugged. “You can,” he said. “If you know what you want them to do.”

Mills exchanged a look with Sergeant O’Rourke, who had just ducked into the ruined barn with a coil of field telephone wire over his shoulder.

“He’s been like this all morning,” Mills muttered. “Ever since that heavy tank rolled past our foxholes like we weren’t even here.”

O’Rourke set the wire down with a grunt.

“You planning to punch through its armor with that?” he asked, nodding toward Jim’s modified ammo. “Because in case you missed it, their tanks are not made of tin cans.”

Jim finally looked up.

“No,” he said. “But I might not need to punch through the big parts.”

O’Rourke folded his arms.

“If this is about that story your uncle told you—” he began.

“It’s about the spots no one else bothers aiming for,” Jim cut in. “The vents. The seams. The places they don’t think anyone will hit because they’re small and moving.”

Mills shook his head. “You keep talking like that, the captain’s going to sign you up for the ‘intense evaluation’ program,” he said. “You know—the one where they give you a nice jacket that buttons in the back.”

Jim went back to filing.

He could still see it from that morning—the heavy tank, German markings, rolling down the village’s main street. The turret had scanned lazily, gun barrel over their heads. A machine gun had swept the upper windows. Brick dust had rained down into their hair.

The anti-tank gun they were supposed to have covering that lane had been knocked out by a shell before it fired its first shot. The bazooka team had been caught in an alley, pinned by debris.

So the tank had driven past them, completely unbothered by the existence of six riflemen in a cellar who could do nothing but watch.

Jim had never liked being helpless.

“Look,” O’Rourke said, softer. “I get it. Nobody likes seeing those things roam free. But rifles are for people, not for armor. You want to kill tanks, you wait for a bazooka or a cannon. That’s how this works.”

“Maybe,” Jim said quietly. “Maybe this is how it worked before.”

O’Rourke sighed.

“You’ve got orders to sit tight here until dusk,” he said. “Do me a favor and don’t blow yourself up with your ‘science project’ before then, huh?”

He slung the telephone wire back onto his shoulder and ducked out into the cold.

Mills lingered.

“You know what they’re saying about you?” he asked.

“That I’m weird?” Jim said.

“That and…” Mills shrugged. “That maybe you see things the rest of us don’t. Last month at the crossroads, you hit that machine gunner when all I could see was smoke and dust. That kind of thing makes people pay attention, even when you start filing bullets.”

Jim set down the file.

“It’s not magic,” he said. “It’s just… paying attention longer than the other guy.”

Mills shifted his weight.

“You’re going to try them on a tank, aren’t you?” he asked.

“If one comes close enough to make fun of us again,” Jim said, “yeah. I’m going to try.”

Mills shivered for reasons that had nothing to do with the cold.

“Just… don’t tell me exactly what you’re doing,” he said. “If the officers ask, I’d like to be able to say I had no idea.”

He left before Jim could answer.

Alone again, Jim picked up another standard round from the ammo box, rolled it between his fingers.

The file bit into the jacket with a faint, steady rasp.

He didn’t know if any of this would work.

He only knew that doing nothing wasn’t an option he could live with.

The first time Jim had thought seriously about “secret ammo,” he’d been fourteen and bored in his uncle’s garage.

Uncle Ray had been the sort of man who took everything apart to see how it worked, then, more often than not, reassembled it into something that probably broke some kind of law.

They’d been cleaning an old hunting rifle when Ray had reached into a drawer and pulled out a little cardboard box with no markings.

“What’s that?” Jim had asked.

“Special loads,” Ray had said.

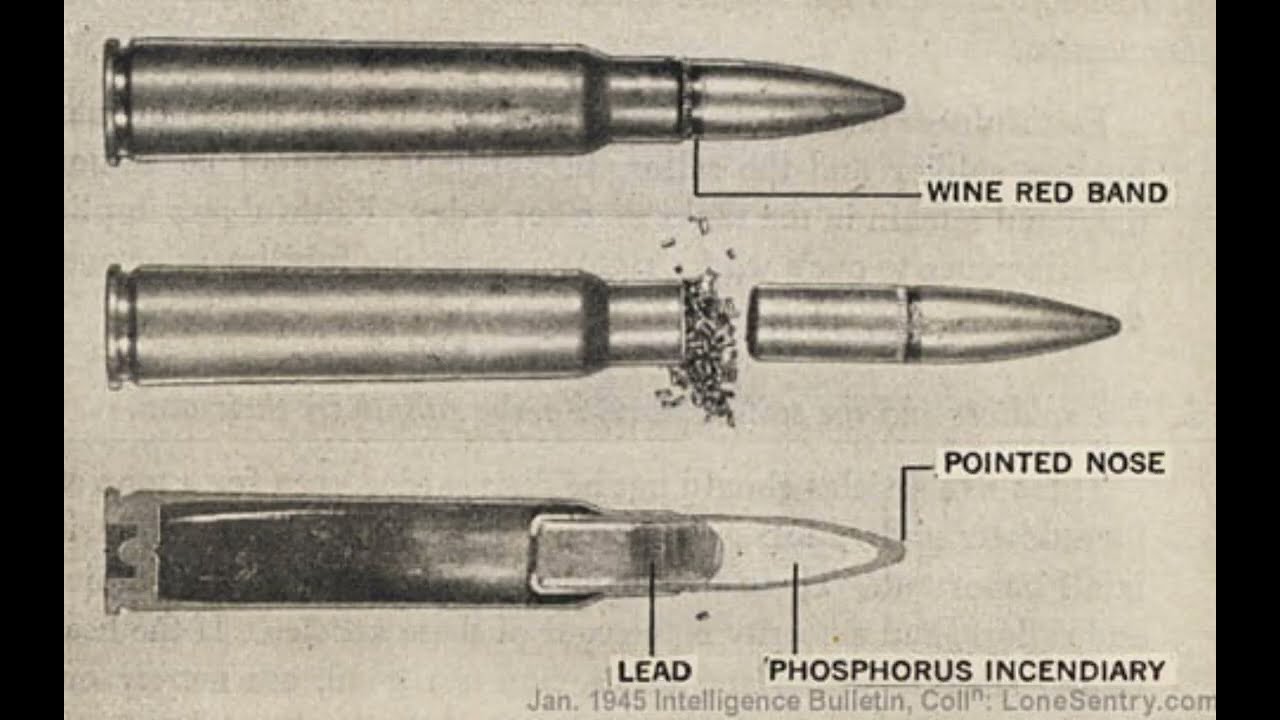

He’d cracked the box open and tipped a round into his palm. The bullet looked odd—blunt-nosed, with a small, dark plug in the tip.

“See,” Ray said, “most bullets are just metal. These have a little surprise inside. You hit something hard, they break open, and what’s inside likes to catch fire.”

“Is that… allowed?” Jim had asked.

Ray had winked.

“Depends who you ask,” he said. “Law says you’re not supposed to use them on people. Animals neither, far as I’m concerned. But for shooting at junk in the scrap yard? They’re fun. And if you ever have to stop something that doesn’t care about normal holes…”

He’d shrugged.

“Just good to know they exist.”

Jim had never fired one.

He’d watched Ray demonstrate on an old engine block from across the yard. The bullet had hit, and instead of just making a neat crater, it had sent sparks and a small, angry flame licking out of the dent.

“See?” Ray had said, pleased. “Little fire right where the metal’s weakest. Not a toy, but a tool.”

Years later, in a different country, crouched behind a burned-out wagon, that memory came back to Jim as he watched another tank roll by.

They called this one a Panzer.

He called it a problem.

That was the day he started thinking about how to turn a rifle round into something that might act a little like those old “surprises.”

Not with any fancy explosive—he didn’t have that, and he wasn’t crazy enough to start mixing powders in a barn in the middle of a war.

But he did have access to some armor-piercing rounds from the machine gun belts. And he had a file. And he had an uncle’s lesson echoing in the back of his mind:

If you can’t go through the front door, find the cracks.

It was two mornings after the barn scene when the Panzer gave him his chance.

They’d pulled back from the village overnight, relocating to a line of low hedges and shell holes overlooking a stretch of muddy road. The road curved around a stand of trees before disappearing toward a small bridge—one the officers were very keen on not losing.

The engineers had laid charges on the bridge “just in case.” The anti-tank gun that had been knocked out in the village had been dragged back and patched up, now sitting in a shallow scrape with its barrel pointed toward the curve.

The fog that morning was thick enough to taste. It flattened colors, turned shapes into suggestions.

Jim lay in a foxhole scratched into the far side of a shallow ditch, his rifle resting on the lip. The modified rounds sat in a small pouch at his chest, separate from the standard ones.

He’d made only four.

Four hand-filed, sharpened, carefully inspected rounds.

Four chances, at most, to find out if he was crazy or onto something.

Mills slid into the hole beside him, breathing hard from the short run.

“Tank’s moving,” he whispered. “Heard it from the forward OP. Big one.”

Jim nodded.

“How’s the gun?” he asked, meaning the anti-tank piece.

“Operational,” Mills said. “But the last shell of the test fired last night made the barrel sound… wrong.”

Jim didn’t like the sound of that.

“Barrels aren’t supposed to sound like anything,” he said.

“Exactly,” Mills replied.

The rumble came first—a low vibration in the packed earth under their elbows.

Then the clank of treads.

Then, faintly, the creak of metal under strain.

The fog at the curve thickened, then parted as a dark shape grew in it like a nightmare becoming real.

“Panzer,” someone hissed down the line, as if there had been any doubt.

It rolled into view—armor plates dull, tracks churning mud, turret turning in a slow, lazy arc as if sniffing for threats.

Behind it, shrouded by mist, shapes of other vehicles loomed—half-tracks, perhaps, or more tanks. Jim couldn’t tell.

“Wait for the gun,” O’Rourke’s voice carried softly. “Hold all fire till the AT gun speaks.”

The anti-tank crew huddled around their weapon, loader ready with the first shell.

“Range?” the gunner muttered.

“Two hundred,” the spotter replied. “Maybe a hair more.”

The Panzer came around the curve, presenting its frontal armor to the gun, its side to Jim.

“Now,” the gunner said.

The AT gun fired.

The shell hit the front of the tank with a hollow, metallic bang. A puff of smoke and dust erupted from the impact point. For a heartbeat, it looked promising.

Then the tank kept rolling.

“Ricochet,” the spotter cursed. “Too shallow.”

They hurried to load another shell, but something in the gun groaned ominously as the breech slammed shut.

“Fire!” the gunner snapped.

The second round left the barrel with less conviction. It flew short, hitting the ground just in front of the tank and showering it with dirt.

The gun’s barrel sagged slightly, a hair out of true.

“Barrel’s warped,” the loader gasped. “We keep firing, it’ll blow.”

The Panzer’s turret snapped toward the gun crew now, its own barrel swinging to bear. Its machine gun chattered, stitching the ground around the AT position with dirt geysers.

Men dove for cover.

Behind them, Mills swallowed hard.

“We are out of good ideas,” he said.

“Not all of us,” Jim replied.

He reached into the pouch, fingers finding the first of his four modified rounds, the metal cool and slightly rough where he’d filed it.

“Jim,” Mills said, alarm creeping into his voice. “Tell me you are not—”

“Got a better option?” Jim asked calmly.

Mills shut his mouth.

The Panzer was still moving, but slowly now, engine growling as it adjusted to the sudden opposition.

Jim scanned its side, eyes catching on every detail: the road wheels caked with mud, the side skirt plates, the faint seams where armor met armor.

He wasn’t looking for the big flat parts.

He was looking for the little ones.

There—just behind the turret ring, a rectangular grille in the side armor, covered with slats.

Engine vent.

Hot air and fumes streamed out there when the tank had been running hard. Ray’s voice echoed in his head: “Little fire right where the metal’s weakest.”

Even a small spark in the wrong place could do big things.

“Come on,” Jim muttered. “Show me you’re overworked.”

As if on cue, a thin haze of exhaust leaked from the grille, curling in the cold air.

Jim slid the modified round into the chamber, the bolt closing with a satisfying, familiar click.

The distance wasn’t extreme—maybe seventy meters. The target, though, was no bigger than a shoe box and partially moving.

He didn’t think about the odds.

He thought about the way the filed bullet would behave—more likely to grab and bite instead of glance.

He aimed a fraction low, letting the slight upward angle of the vent do some of the work.

He fired.

The rifle cracked, recoil nudging his shoulder.

The bullet hit the grille with a sharp, high sound, different from the dull thud of metal on thick armor.

Sparks flew.

For a moment, nothing else happened.

Then a brief tongue of orange flame flickered inside the vent, there and gone like a match struck in a cave.

“Did you see that?” Mills whispered.

“Yep,” Jim said. “Three left.”

He worked the bolt, chambered another modified round.

The tank, not yet understanding that anything serious had happened, rotated its turret further toward the AT gun that had dared to challenge it. Its machine gun spat again, raking the abandoned position.

Jim fired his second shot into the same vent.

This time, the sparks were brighter. The little flame hesitated, then bit into something behind the grille and flared.

A faint popping sound came from inside the tank’s hull—like someone shaking a box of nails.

Hot air being forced through the vent met cold oxygen-rich air outside. Tiny fragments of burning material were blasted out, sparkling in the morning murk.

Inside, Jim guessed, fuel fumes or oil residue had caught.

The Panzer lurched.

“Something’s wrong with it,” Mills breathed.

“Good,” Jim said through his teeth. “Let’s make it worse.”

He lined up his third shot, not at the vent this time, but just below it, where he’d noticed a slight gap where the hull side met an access panel.

The filed tip of the bullet would have an easier time biting into that seam.

He fired.

The impact sounded different again—more of a crack, less of a ping. The bullet disappeared into the narrow line between plates.

This time, the result was less subtle.

A dull boom thudded inside the tank’s hull, muffled but unmistakable.

The engine snarled and then coughed.

A gout of black smoke belched from the rear exhaust.

The Panzer’s forward motion slowed, then stopped altogether, tracks grinding to a halt.

“Holy…” Mills started, then caught himself.

“Language,” Jim said automatically, even as his heart hammered.

The tank’s turret jerked, then froze halfway through its rotation.

Inside, men were shouting. Jim couldn’t hear the words, but he recognized the pitch—panic.

He had one modified round left.

“Lot of other things on that thing,” Mills said. “You going for more vents?”

Jim shook his head.

He was already shifting his aim toward the turret.

He’d noticed, as it rolled, a small, round protrusion on the turret’s left cheek—an auxiliary sight for the gun, with a thin armored hood and, just beneath it, a narrow slit.

Optical ports were more delicate than steel. Behind that slit would be glass. Behind the glass would be a man’s face.

He didn’t want the man.

He wanted what might be stacked near that location.

Some tanks stored small ready-use shells near the turret front. He’d seen diagrams. He’d also seen one go up once when a stray hit had set off propellant charges.

“Last shot,” he murmured. “Make it count.”

He exhaled, steadied, felt everything else drop away.

The filed bullet slid down the barrel, gathering spin.

It punched through the thin metal hood protecting the sight, shattered the glass behind it, and entered the turret compartment in a spray of fragments.

For a brief, terrible instant, nothing happened.

Then, somewhere inside that cramped steel world, something stored where it shouldn’t have been met heat it wasn’t meant to feel.

The Panzer bloomed.

Flame burst from the shattered sight, from the open commander’s hatch, from the engine vents already dancing with fire. It wasn’t a cinematic, towering explosion—more of a violent, concentrated whoomph that blew every loose piece of gear on the hull outward and upward.

The turret hatch flew open. A figure tried to climb out, was caught by the sudden rush of hot gas, and tumbled backward inside.

The tank rocked on its suspension.

The sound that reached Jim’s foxhole was low and heavy, like a giant exhaling the last of its anger.

Mills stared, eyes so wide they looked ready to fall out.

“You… you just…” he stammered. “Four shots. Four. From a rifle.”

Jim didn’t answer.

His throat was tight.

Down the line, men were shouting. Some in disbelief, others in triumph. A few just in sheer, unfiltered excitement.

The tank behind the Panzer—still obscured by fog—threw its transmission into reverse so fast its engine screamed. Its driver had seen enough.

“Keep firing!” O’Rourke yelled. “Before they remember they’ve got more than one!”

Rifles and machine guns opened up. Grenades arced. The anti-tank gun, coaxed into one more shot with a lighter practice round, fired at a half-track trying to change lanes around the stricken Panzer.

Jim kept his eye on the burning tank.

Its paint blistered. Ammunition inside cooked off in pops and cracks. One of the side hatches blew open, then slammed back shut as something inside shifted.

“How did you know that would happen?” Mills breathed.

“I didn’t,” Jim said honestly. “I only knew that if I hit nothing, we’d still be stuck.”

He glanced down at his rifle, then at the small, empty pouch that had held his modified rounds.

“I just gave the fire something to eat,” he added softly.

They pulled him off the line within the hour.

Not because he’d done something wrong.

Because, as O’Rourke put it, “You just did something that gives everyone in a ten-mile radius very strange ideas.”

The battalion commander wanted to see him.

Captain Lewis, a man with thinning hair and a tired face perpetually in need of a shave, stood in the shell-scarred farmhouse that served as headquarters, a chipped enamel mug of coffee cooling on the table beside a stack of reports.

He looked up as Jim entered, escorted by O’Rourke.

“That your work?” Lewis asked without preamble, jerking a thumb in the vague direction of where the Panzer still burned.

“Yes, sir,” Jim said.

“With a rifle,” Lewis said.

“Yes, sir.”

Lewis stared at him for a long moment, then sighed.

“Sit,” he said.

Jim sat.

He rested the rifle across his knees. It felt heavier than it had an hour ago.

Lewis picked up a piece of paper from the stack.

“Do you know what this is?” he asked.

“Report, sir?” Jim guessed.

“Three reports,” Lewis corrected. “One from the AT gun crew—what’s left of it, anyway. One from Sergeant O’Rourke. One from a scout who says he watched the whole thing through his binoculars and nearly fell out of his tree.”

He read, the corner of his mouth twitching faintly.

“Says here,” he went on, “that one Corporal James Hartley ‘engaged an enemy armored vehicle with four rifle shots, hitting critical points and causing catastrophic internal failure.’”

He set the paper down.

“You understand why that sentence makes me feel both extremely relieved and extremely uneasy?” he asked.

Jim swallowed.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “It sounds like something you’d fire the man who wrote it for making up.”

Lewis snorted.

“Exactly,” he said. “Thing is, I’ve known O’Rourke too long to think he’d spin me a fairy tale in the middle of a battle. And the scout’s account matches the timing. And Mills is still babbling about ‘secret bullets’ like a boy who just saw a magic trick.”

He leaned forward, elbows on his knees.

“So I’m going to ask you one question,” Lewis said. “Straight. No politics. No manuals. How did you do it?”

Jim told him.

He talked about Uncle Ray’s demonstration with special rounds, about the filed tips from machine gun belts, about vents and seams and sight ports.

He emphasized—more than once—that there had been as much luck as skill involved. That the tank had been moving slowly. That the vents had been hot. That the ammunition inside had probably been stacked wrong or poorly secured.

Lewis listened without interrupting, his fingers steepled under his chin.

When Jim finished, there was a long silence.

Finally, Lewis spoke.

“If it was just luck,” he said, “I’d chalk it up as a fluke and tell everyone to stop dreaming. But you aimed at specific weak points. You had a rationale. You made something weird happen on purpose.”

He shook his head.

“You know what the problem with that is?” he asked.

“Sir?” Jim said.

“The problem,” Lewis said, “is that if you can do it, someone else can learn to do it. If that idea spreads, we’re going to have a lot of very enthusiastic young men filing bullets and taking potshots at tanks in situations where they should be doing other things.”

He held up a hand as Jim started to protest.

“I’m not saying what you did was wrong,” Lewis said. “An enemy tank died and ours didn’t. That’s a good trade in any language. I’m saying that ideas are like—”

He searched for a word.

“Like those little fires you just started,” he settled on. “Once they get into the wrong places, they’re hard to control.”

He reached for his mug, then seemed to remember the coffee had gone cold and thought better of it.

“Someone up the chain is going to want to talk to you,” he said. “Ordnance. Intelligence. Maybe both. They’ll want to know exactly what you did. They’ll want to see if it can be turned into a formal program. They’ll want to keep it out of the enemy’s hands.”

He sighed.

“And while they do that,” he added, “they’re not going to want you on the line where you might improvise something else surprising.”

Jim blinked.

“Sir?” he said slowly.

“You’re being pulled,” Lewis said. “Orders just came down. You’re to report to the rear for ‘evaluation and possible reassignment to experimental weapons section.’ Effective immediately.”

Jim stared.

“I’m… I’m being removed?” he asked.

“Relocated,” Lewis corrected mildly. “Never say ‘removed’ on paper. Looks bad.”

He grimaced.

“Look,” he said. “If it were up to me, I’d keep you here, doing what you do to people with your nice, ordinary, regulation-approved ammo. You’ve been good for the men. They’ve started to believe that if Hartley’s watching, less bad stuff happens.”

He spread his hands helplessly.

“But it’s not up to me,” he said. “Some colonel saw that sentence about a rifle killing a tank and saw a research opportunity and a security risk all wrapped in one. They don’t want the story getting out uncontrolled. They don’t want the enemy remembering they’ve got vents and seams too.”

He held Jim’s gaze.

“And maybe,” he added, “they’re a little uneasy about soldiers who are too creative for their own comfort.”

Jim swallowed.

“With respect, sir,” he said, “I didn’t do it to be clever. I did it because we were out of other ways to stop that thing.”

“I know that,” Lewis said. “And if they ask me, I’ll tell them. But their job is thinking about the war as a giant board. Mine is keeping as many of you breathing as I can. Right now, that means letting them take you.”

He glanced toward the door, where the distant sound of gunfire still rolled like weather.

“I’ll tell the men you’ve been sent to show the lab boys how to do things right,” Lewis added. “Give them something to brag about.”

Jim forced a smile.

“Tell Mills I didn’t blow myself up,” he said.

“I’ll add that detail,” Lewis replied.

He stood.

“You’ve got an hour to pack what you need,” he said. “Truck leaves at sixteen hundred. I’m not giving you a choice. Consider that an order.”

Jim stood too, automatically.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

At the door, he paused.

“What happens to the tank?” he asked.

Lewis raised an eyebrow.

“The burned-out one down the road?” he said. “We’ll try to pull it off the road eventually. Or blow it off if we can’t. Why?”

“Pieces,” Jim said. “If the ordnance guys want to know what happened inside, someone should look. Even a glance might help. Vents, ammo, fuel lines…”

Lewis nodded slowly.

“I’ll mention it,” he said. “Now get moving, Corporal. Before somebody changes their mind and decides to try your scheme on every man with a file.”

The rear area smelled different.

Less cordite, more diesel.

Fewer sudden sharp noises, more drones of engines and clatter of tools.

They put Jim in a drafty barracks with other men pulled from the line for various reasons—some wounded, some specialists, some simply too valuable to keep where the metal flew thickest.

Three days after he arrived, an ordnance major with ink-stained fingers and a clean uniform summoned him.

Major Rhodes didn’t bother with small talk.

“You’re the tank shooter,” he said, flipping through a thin file.

“I was a rifleman,” Jim said. “Once. On one day… something happened.”

“Something,” Rhodes echoed dryly. “That’s one way to put it.”

He laid out a set of photographs on the table.

Black-and-white images of the Panzer sat between them—one showing the side vent, blackened and twisted; another the shattered auxiliary sight port; a third, taken from inside the turret, charred and warped.

“We sent a recovery team,” Rhodes said. “Nearly cost us a wrecker. Some of the shells inside hadn’t fully cooked off. But we got enough to see your handiwork.”

He tapped the photo of the vent.

“This is where your first and second rounds hit,” he said. “Residue suggests you had something hotter than standard ball on those tips.”

He looked up.

“You want to tell me what it was?” he asked.

Jim hesitated.

“Armor-piercing cores from the MG belts,” he said. “Filed a bit. Tried to make them more likely to bite instead of glancing.”

“Filed how?” Rhodes pressed.

Jim described it again—the way he’d shaved the jackets, the care to keep the tips balanced, the idea of creating a sort of improvised penetrator that also sparked more on impact.

Rhodes listened, occasionally jotting notes.

“You do this often?” he asked.

“First time,” Jim said. “Might have been the last if it had gone wrong.”

“Why only four?” Rhodes asked.

“Didn’t want to gamble too much with untested rounds,” Jim said. “If they’d done something ugly in the chamber…”

He trailed off.

Rhodes sat back.

“You understand why the higher-ups are both excited and nervous, then,” he said. “On the one hand, you demonstrated that a determined, skilled marksman with adapted ammunition can threaten armored vehicles, at least in some conditions. On the other hand, you did it with improvised, untested modifications.”

He shuffled the papers.

“We don’t want every infantryman out there filing bullets and blowing his own hand off,” he said. “Nor do we particularly want this trick getting back to the enemy so they can start teaching their boys to take potshots at our vents.”

He tapped the file.

“Officially,” he said, “this is classified. Your name, the details, the photos—all restricted. If anyone asks you about that day, you tell them you engaged soft targets and helped with suppression. You do not mention four shots and a tank burning from the inside.”

Jim nodded slowly.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“Unofficially,” Rhodes added, “we’re going to see if there’s a way to do something like this safely. Controlled. In a lab. With the right alloys and tests. Maybe we come up with a special-purpose round for trained people. Maybe we decide it’s not worth the trouble. But either way…”

He closed the folder.

“Either way, your part in this war is over,” he said. “At least at the front.”

Jim opened his mouth, closed it.

“Sir,” he said, “with respect… I can still help. On the line, I mean. To people. I know how to—”

Rhodes raised a hand.

“I read your record,” he said. “You’re good. Very good. That’s part of why they don’t want you eating a random piece of shrapnel tomorrow. You’ve shown you think around corners. The people in the big tents want that thinking directed at problems with schematics and safety distances, not at snap decisions under fire.”

He leaned forward.

“I get it,” he said quietly. “You left men behind. Men you care about. They’re still out there. You feel like you’ve been… exiled.”

Jim stared at the tabletop.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

Rhodes sighed.

“If it helps,” he said, “the things we figure out here might keep some of them alive. There are worse ways to fight a war than making weapons that mean fewer of ours have to stand directly in front of theirs.”

He gave a faint, tired smile.

“And maybe,” he added, “keeping you here means we don’t wake up one morning to reports that some inspired corporal tried to blow up a tank by shooting its fuel cap at two hundred yards and turned himself into a cautionary tale.”

Jim’s mouth twitched reluctantly.

“Suppose that would be bad,” he said.

“Very messy paperwork,” Rhodes agreed.

He stood.

“You’ll be assigned to the experimental range starting tomorrow,” he said. “You’ll help test different bullet designs. You’ll give feedback. You’ll teach the lab boys that not everything that looks good on a blackboard works when you’re lying in the mud.”

He paused.

“And if you absolutely must file something,” he added, “we’ll at least make sure it’s made for it.”

The range was a different kind of battlefield.

Instead of enemies who shot back, there were rows of test plates, fuel drums, old vehicle hulks hauled from junkyards.

They gave Jim lab-made armor-piercing rounds and incendiaries and asked him to shoot them at various spots, then took notes as if his comments were as important as the holes themselves.

Some days, it felt trivial compared to the foxholes and hedges he knew his old squad was still crouched behind. Other days, when a new design showed real promise—when a bullet behaved predictably and effectively against a mock-up of a vent or a hatch—he felt a small, guilty thrill that maybe, somewhere down the line, someone might have an easier day because of this.

He never forgot, though, that the spark for all of it had come from a moment of desperation and four improvised rounds in a barn.

The story of “the man who blew up a tank with four 7.62 shots” didn’t die.

It just went underground.

Among the men he’d fought with, it became a quiet legend, told in low voices when someone new came to the unit.

“You know Hartley?” Mills would say. “The one they pulled off the front? Let me tell you what he did before they decided he was too interesting to keep…”

Details shifted. Sometimes it was three shots, sometimes five. Sometimes the “secret ammo” was described as something out of a science fiction magazine, handed to him by a mysterious figure from the rear.

Jim chose not to correct those stories.

It was better that way.

Let the myth be a little bigger, a little fuzzier. Myths, he’d learned, had their uses. They gave men something to smile about in bad weather.

The facts stayed in folders marked RESTRICTED, filed in cabinets in rooms he never saw.

Years after the war, when documents began to be declassified and historians started sifting through crates of memos and reports, a few came knocking on his door.

“Mr. Hartley?” one young researcher asked, notebook at the ready. “We’ve been looking into the origins of certain armor-defeating small-arms concepts, and your name keeps popping up.”

Jim, older now, hair thinner but eyes still sharp, invited him in.

They talked over coffee.

The researcher laid out copies of yellowed reports. Some were stamped SECRET in big, fading letters. Others bore his name in crisp typewriter font.

“This incident,” the researcher said, tapping the account of the Panzer, “is considered one of the earliest recorded cases of a rifle being used deliberately against the weak points of a tank with modified ammunition. It’s cited in later doctrinal debates. Some credit it with influencing postwar thinking about precision weapons.”

He looked up, eyes bright with academic curiosity.

“How did it feel,” he asked, “to have your own army pull you from the fight because of something you did right?”

Jim thought about it.

“At the time?” he said. “It felt like… punishment for trying.”

“And later?” the researcher pressed.

“Later,” Jim said slowly, “I decided to be grateful I got to grow old enough to think about it.”

He took a sip of coffee.

“You know,” he added, “they were probably right to pull me. Not because I did something wrong, but because they were trying to keep the whole crazy idea under control.”

The researcher frowned.

“Do you wish,” he asked, “that they’d let you keep doing it? That they’d made more ‘secret ammo’ for you and others?”

Jim considered the question carefully.

“I wish,” he said, “we’d needed fewer days when tanks and rifles had to have that conversation at all.”

He set his mug down.

“If we were going to be in that mess either way,” he went on, “then yes… I’m glad we found ways to give the guys on the ground a little more leverage. But I also saw enough to know that every new trick we discover has a way of coming back around later in someone else’s hands.”

He gave the researcher a wry smile.

“You start with a filed bullet in a barn,” he said. “Next thing you know, you’ve got guided missiles. Different tools, same questions.”

The researcher scribbled notes.

“One last thing,” he said. “Those four shots. Do you remember them clearly?”

Jim closed his eyes.

He did.

The way the metal had felt under his file.

The way the vent had flickered.

The way the turret sight had exploded outward in a brief, bright spray.

“Yes,” he said simply.

“Do you ever regret taking them?” the researcher asked.

Jim thought of the anti-tank crew scrambling away from a warped barrel. Of Mills’ face when the tank rolled past them in the village, helpless. Of the men in that Panzer who had not walked away.

“I regret the war,” he said. “I regret that we were in a position where the best thing I could do for my own side was to find clever ways to break someone else’s machine.”

He looked out the window, where a car drove past on a quiet street, its engine a far, peaceful hum.

“But those four shots,” he added quietly. “No. I don’t regret those. There was a tank that needed stopping. We were out of approved methods. I did what I could with what I had.”

He met the researcher’s eyes.

“What I regret,” he said, “is that when young soldiers hear that story, some of them will hear only the part where a rifle blew up a tank, and not the part where the man with the rifle spent the rest of his war making sure no one tried something that dangerous by accident.”

The researcher closed his notebook.

“That’s going in the book,” he said.

Jim smiled faintly.

“Make sure you spell my name right,” he said. “The rest… people will tell it how they want.”

In the end, the story settled somewhere between secret and legend.

Some would remember him as “the guy with the secret ammo,” as if he’d carried a pouch of magic bullets no one else could have.

Others, reading dry doctrinal papers, would know him as “Cpl. J. Hartley, whose actions suggest that precise application of armor-piercing rifle fire can have disproportionate effects when aimed at vulnerable points of armored vehicles.”

He lived out his days quietly, working with tools that made fences instead of holes.

Sometimes, when he heard a truck backfire, his mind flickered back to that morning on the road, the burning Panzer framed in fog.

Mostly, though, he thought about filed bullet tips only when he picked up a woodworking chisel and felt the familiar rasp of metal on stone as he sharpened it.

One tool, many uses.

In the right hands, a way to build.

In the wrong moment, a way to break.

The war had taught him which one he preferred.

THE END

News

They Flaunted Their Wealth, Mocked the Tip Jar, and Flat-Out Refused to Pay the Waitress — Until the Quiet Man at the Corner Booth Revealed He Was the Billionaire Owner Listening the Whole Time

They Flaunted Their Wealth, Mocked the Tip Jar, and Flat-Out Refused to Pay the Waitress — Until the Quiet Man…

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her Laughed—Until the Screen Changed, and the Truth Sparked the Hardest Argument of His Life

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her…

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind the $600 Million Deal That Was About to Decide Every One of Their Jobs and Futures

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind…

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the Millionaire in Line Behind Him Heard Everything—and What Happened Next Tested Pride, Policy, and the True Meaning of Help

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the…

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up a Doll, Looked Under the Bed, and Uncovered a Hidden “Secret” That Nearly Blew the Family Apart for Good

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up…

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really on His Plate and the Argument That Followed Changed Everything About What He Thought Money Could Buy

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really…

End of content

No more pages to load