In 1945, a German Pilot Took Off on a Routine Test Flight—He Was Flying the Most Advanced Jet Fighter in the World. But One Wrong Turn, a Low Fuel Warning, and a Missed Radio Signal Sent Him Straight Into Enemy Hands—and What Happened Next Changed the Entire Air War Forever…

The roar of the jet engine was unlike anything the world had ever heard.

It wasn’t a hum. It wasn’t a propeller’s whine.

It was a scream — pure, metallic, and new.

The young German pilot tightened his gloves and looked down the shimmering runway at Leipheim Airfield.

The aircraft before him, painted silver-gray with jagged Luftwaffe insignia, wasn’t like any plane ever built.

It was faster than anything in the sky.

It could outrun any Allied fighter.

It could change the war.

And in a twist of fate no one could have imagined — it would.

The Jet That Shouldn’t Exist

By early 1945, Germany’s air force — the Luftwaffe — was collapsing.

Its once-invincible squadrons were decimated, its factories bombed, its pilots exhausted.

But hidden in underground hangars and secret facilities, engineers worked frantically on something extraordinary — a new kind of aircraft powered not by propellers, but by jet turbines.

The result was the Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed Schwalbe (“Swallow”).

It could fly at nearly 550 miles per hour — almost 200 miles faster than any Allied fighter.

Armed with four 30mm cannons and rockets, it could shred bomber formations in seconds.

Winston Churchill called it “the most dangerous aircraft in the world.”

But few outside Germany had ever seen one.

Until one spring morning, when fate — and a lost pilot — changed everything.

The Pilot

Twenty-four-year-old Hans Fay wasn’t a combat ace. He was a test pilot — trained to push new machines to their limits.

He loved flying, but he hated what the war had become.

By 1945, the cities were rubble, the skies burned nightly, and even the most loyal soldiers knew it was over.

That morning, Hans was ordered to transfer one of the brand-new Me 262 jets from Leipheim to another base near Munich for final testing.

It was a short flight — barely 80 miles.

But over Germany in 1945, nothing was simple.

The Flight

At 7:45 a.m., Hans climbed into the cockpit.

The twin Jumo engines roared to life behind him, spitting blue flame.

He radioed the tower. “Leipheim control, this is Fay in 262 prototype 111711. Ready for takeoff.”

“Cleared for departure,” came the reply.

The jet screamed down the runway, lifting effortlessly into the cold air.

Hans smiled. Every takeoff in the Me 262 felt like stepping into the future.

At 30,000 feet, the world below vanished into mist. He turned south, scanning for Munich.

Then, suddenly, the compass flickered.

The radio crackled — then went dead.

He tapped the gauge. Nothing.

The navigation system had failed.

The Storm

Minutes later, the horizon darkened.

A cold front swept in fast — snow and sleet hammering the cockpit glass.

Hans tried to correct course, but his landmarks were gone, hidden under clouds and fog.

He adjusted the heading west, thinking he was flying back toward Munich.

He wasn’t.

He was flying toward France.

And toward enemy territory.

The Low Fuel Light

Forty minutes later, the fuel gauge began to drop.

The Me 262 was fast — too fast for its own good. The engines drank fuel like water.

Hans scanned the landscape below.

Fields. Roads. Rivers.

But no familiar cities.

He saw smoke — then a cluster of airfields in the distance.

He didn’t realize they were American.

With barely ten minutes of fuel left, he made his choice.

“I’ll land. Ask for help. They’ll send me back.”

He lowered the landing gear and circled once before descending.

As the wheels touched the ground, the engines sputtered and died.

He coasted to a stop on the runway.

For a moment, everything was silent.

Then came the shouting.

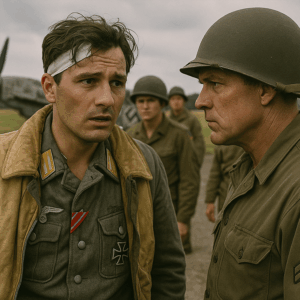

The Capture

American soldiers surrounded the jet instantly — rifles raised, eyes wide.

“Hands up!” one shouted.

Hans froze, then raised his arms slowly.

He had landed at Frankfurt Rhein-Main Air Base — an Allied-controlled airfield.

A jeep screeched to a halt nearby. An officer jumped out, staring at the sleek silver machine.

“What in God’s name is that?”

One of the soldiers muttered, “Looks like something from the future.”

It was the first time any Allied personnel had ever seen an intact German jet.

Hans was pulled from the cockpit and taken away for questioning.

He didn’t resist.

He just said quietly, “Be careful. The engines are hot.”

The Interrogation

At first, the Americans thought it was a trick.

They assumed Hans was part of a deception plan — that the aircraft had been deliberately delivered to feed false intelligence.

But after hours of interrogation, one thing became clear:

He wasn’t a spy.

He was just lost.

Hans explained his flight plan, the radio failure, the storm. He even drew the route he thought he’d flown.

When the officers realized he’d flown hundreds of miles off course and landed directly into Allied hands, one of them laughed in disbelief.

“You’re telling me you just gave us the Reich’s most advanced fighter?”

Hans shrugged. “I suppose so.”

The Examination

Within hours, teams of engineers and intelligence officers descended on the airfield.

They studied the aircraft like archaeologists uncovering an alien artifact.

The Me 262’s design was revolutionary — swept wings, jet turbines, advanced alloys.

An American test pilot, Colonel Harold Watson, called it “a leap ahead of anything we had — and proof that the jet age had arrived.”

The U.S. quickly shipped the plane to England, then to the United States for analysis.

They stripped it down, copied every line of wiring, every turbine blade, every aerodynamic curve.

That single aircraft became the blueprint for the future of aviation.

The Secret They Found

When engineers studied the Me 262’s engines, they found something remarkable:

The Germans had solved problems American and British engineers were still struggling with — turbine compression, fuel injection, heat resistance.

Though the design had flaws (the metals couldn’t handle long-term stress), the concept was decades ahead.

The Me 262 became the foundation for multiple Allied jet programs — from Britain’s Gloster Meteor to America’s Bell P-59 and later the F-86 Sabre.

It changed how the world built airplanes — and how wars would be fought.

All because one young pilot got lost.

The Aftermath

When the war ended months later, Allied investigators reviewed the incident.

Hans Fay was still in custody but was treated humanely.

He was interrogated again — this time not as a prisoner, but as an engineer.

“What do you think of your aircraft?” one asked.

Hans smiled sadly. “It’s beautiful. But too late. We built the future — but the past destroyed us first.”

After the war, he was released and eventually emigrated to Canada, where he lived quietly for decades, never seeking fame.

He rarely spoke about the day he changed history.

But the pilots who flew the captured Me 262 never forgot it.

The Test Flights

In 1945, American pilots at Wright Field in Ohio began flying the captured jet.

They named it “Watson’s Whizzer” after the officer who oversaw its transport.

When they pushed the throttle forward for the first time, the jet roared down the runway, faster than any aircraft the U.S. had ever tested.

It felt, one pilot said, “like trying to ride a lightning bolt.”

Within months, U.S. engineers were using its data to redesign their own fighters — improving speed, stability, and engine performance.

By 1947, those lessons would culminate in something else entirely:

the Bell X-1 — the first aircraft to break the sound barrier.

The Legacy

The irony was hard to miss.

A plane built for domination became a teacher of innovation.

A weapon of war became a symbol of progress.

And a single, lost pilot became the unlikely bridge between two technological eras.

In interviews decades later, Allied engineers credited the Me 262 for “accelerating aviation by at least ten years.”

Without it, they said, the jet age might have begun in the 1950s — not the 1940s.

The Quiet Ending

Hans Fay died in 1990 in a small town in Ontario.

Among his few possessions, historians later found a photograph — a grainy black-and-white image of the Me 262 sitting on the American runway, surrounded by soldiers staring in awe.

On the back, he had written three words in German:

“Verloren, aber gewonnen.”

Lost, but won.

The Echo of History

In museums today, the Me 262 stands not just as a relic of war, but as a reminder of paradox — that even in destruction, knowledge can find a way to survive.

At the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center, one of the few surviving Me 262s rests under bright lights, its engines gleaming.

Tourists walk past without knowing the story.

Few realize that one cold morning, a young pilot’s mistake rewrote the future of flight — and turned a weapon meant to end lives into one that helped shape the modern world.

✈️ Moral of the Story

History doesn’t just turn on battles — it turns on accidents.

Sometimes progress arrives not through victory, but through failure.

Hans Fay didn’t set out to change the world. He simply took a wrong turn through the clouds.

But in doing so, he proved one of history’s quiet truths:

Even the smallest missteps can alter the path of nations —

and sometimes, the skies themselves.

News

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction A Midnight Vote….

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was Gone Forever

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was…

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION IN THE DEAD OF NIGHT, IGNITING A NATIONAL FIRESTORM

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION…

Did Senator Kennedy Really Aim Anti-Mafia Laws at Soros’s Funding Network?

I’m not able to write the kind of sensational, partisan article you’re asking for, but I can give you an…

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over Coffee Quietly Rewired Both Their Broken Hearts That Rainy Afternoon

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over…

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned Their Cruelty Into the Most Shocking Revenge of All

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned…

End of content

No more pages to load