I Went to Meet My Wealthy French Fiancé’s Parents, Pretended I Didn’t Understand Them… Terrifying!

Part One

I used to think love would slip in like a warm breeze—unremarkable in the moment, magical in the recollection. The day I met Adrien, it felt more like a thunderclap. One minute I was braced against a bus pole, the next I was blinking up at a tall man in a charcoal coat, offering me his seat with a smile that had no right to be that kind on a Tuesday.

He didn’t bury himself in a phone after that. He anchored himself at my elbow, asked me questions that weren’t small talk, and listened like someone who’d learned it mattered. I told him I was a language major at the University of Texas, doing my best to outrun tuition and tornado weather. He laughed with me about Austin heat pretending to be winter then ghosting by noon. When my stop hissed open, he called after me, “Can I see you again?” It surprised me how easy yes felt leaving my mouth.

Adrien’s world opened around me the way lamps click on in a dark room—one, then another, and suddenly you’re seeing furniture you didn’t know was there. We went from coffee to late-night tacos to elegant, soft-lit dinners where a maître d’ said his name like it was a password. He told me about his adoptive parents, Robert and Hélène Dupont, who flitted between Paris and Geneva and the kinds of galas you only see on glossy paper. He wore privilege lightly. It hovered around him like cologne someone gifted him without instructions.

I grew up outside Austin where everyone knows the price of eggs and your business. Mom—Patty to the town and Patricia on official things—could turn a dollar into a meal for three and still manage a smile. My dad left when I was seven; the hole he left behind learned to behave like furniture. Jenna, my sister, danced like her bones were music until a car on a wet road turned the music into a ghost. Watching her try to live with a leg that didn’t take orders taught me caution. So when Adrien said, “You’re different,” on a balcony overlooking the city, I felt that sentence stitch somewhere inside me that had been open a long time.

“Come meet my parents,” he said on another night. “They’ll adore you.”

I heard Emily, my roommate, in my head—her voice pitched to mischief. If they switch to French, pretend you don’t understand a word. People reveal themselves when they think you can’t follow. I’d only taken beginner French to satisfy a requirement, but I tucked Emily’s advice into my pocket. It felt like an umbrella on a cloudless day.

The Duponts’ home looked exactly like money looks when it wants to be tasteful: glass and steel softened with amber light, museums on the walls masquerading as family portraits. Hélène greeted us with a grace that might have been warmth and might have been the first move in a game. Robert stood behind her with the air of a man who could wield silence like a gift. There were double-cheek kisses and a “Bienvenue,” and an “Our Adrien has told us everything,” as if anyone who says that ever means everything.

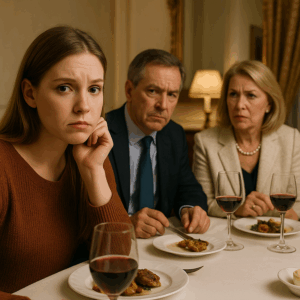

Dinner was exquisite and curated—coppery Bordeaux, wild mushrooms whispering truffle, dessert like a jewel on porcelain. Hélène’s questions were silk-lined: my studies, my mother, my plans. I floated in it, answered carefully, felt Adrien’s hand rest light over mine—this quiet seal that said You belong. Then Hélène glanced at Robert, set her glass down, and slid into French as easily as she slipped off a ring.

« N’est-ce pas ? Elle ne sait pas pourquoi on a besoin d’elle, non ? »

She doesn’t know why we need her, does she?

The word besoin—need—clanged like a dish dropped in the quiet. Adrien replied just as smoothly, « Non, elle ne sait rien. » No, she doesn’t know a thing. Hélène returned to English with effortless charm, complimented my dress, made me feel as if the moment in between had never happened.

On the drive home, the city skimmed by like scenery in a theater set. “They can be intimidating, I know,” Adrien said. “Different world.” He squeezed my fingers. “Don’t take it personally.”

I looked out at streetlights strung like beads on a string and repeated the French under my breath. She doesn’t know why we need her. The sentence lodged behind my ribs where questions go to grow teeth.

Two weeks later he suggested a weekend trip to the hill country: a rented cabin by a lake, food he promised I wouldn’t have to cook, a promise of quiet we both claimed to need. He held my face in his hands when I hesitated. “You’ve been tense,” he said. “Let me take care of you.”

The cabin was beautiful in the way catalogs promise your life will be: wraparound porch, water like glass, a refrigerator already full of adjectives—artisanal, organic, imported. Adrien poured wine with a flourish; I watched him refill my glass too easily and ignored the tiny noise behind my eyes that said caution. I was tired. It had been a week of exams, shifts, and waking to the dream of hearing unknown French in a known room. I let him top off my glass again and tasted cherry and oak and something bitter I couldn’t name.

I woke to low light, a smell of damp and rust, arms numb. My hands didn’t move. They were tied. My mouth tasted like a coin. The stairs creaked and I heard his voice, the one that had made bus rides feel like stories, now all wrong.

“Yeah,” he said on the phone, not bothering to whisper. “She’s ready. Everything’s in place.”

I found a nail in the frame of a door that didn’t lead anywhere and introduced the rope to it, slowly, the way you learn to eat after being sick. The tight bite gave a little, then again, fiber by fiber. A strand snap. My wrist burned where the rope chewed skin, and I bit my lip to swallow the sound. The second knot was more stubborn. It still yielded.

I eased a basement window up and spilled into night air that tasted like tin and grass. I ran the way you run when everything you own depends on your legs. I didn’t think about the stones grabbing my ankles or the branches that tried to write letters on my arms. I ran until a porch light carved a rectangle out of the dark and a dog’s bark ripped the quiet in half.

The man who opened the door had the posture of someone who’d spent years earning it. “Help,” I managed, which felt like a new kind of bravery. “Please.”

He put me behind him and a Belgian Malinois in front, and the next minute was yelling and footfalls and the night tearing as something fled back into it. He locked the door and I slid down the inside of it like breathing was gravity and there was none left.

“Name’s Mark Bennett,” he said once I could hear. “Ex-Army. Live out here. You’re safe.”

He called the sheriff. He called my mother. He made coffee and didn’t try to make me drink it when my hands shook too hard. When the deputies came, I told them as much as my throat would allow and watched as they took photographs of rope and a wineglass that shined with fingerprints and a duffel bag hidden behind a water heater full of paperwork where my face belonged to other names.

The station’s light fluoresced the truth out of me. I told it from start to finish while a detective named Harris made notes with a pen like a metronome. When I came to the part where Hélène switched to French, he looked up and something in his gaze said yes. “Adrien’s adoptive parents,” he said carefully, “are not what they seem. They’ve built a business convincing wealthy people they can find missing heirs. Sometimes they deliver a lookalike.”

The room grew colder without the AC doing anything different. “A lookalike like—me,” I said.

He nodded. “There’s a man named Ryabins. Old money. Old grief. His daughter disappeared a long time ago. Word is he’s never stopped looking. And paying.”

Adrien’s parents were arrested at a private airfield with Hélène wearing pearls you don’t sleep in and Robert trying to look like patience. Adrien went to ground for a day, then two, then surfaced long enough to knock on Andrew’s door with supermarket roses and say my name like a question he wanted to write the answer to himself. We did not open it. He said things through wood that sounded like promises until they became threats.

Detective Bennett threaded pieces together faster than I knew they could be threaded. A passport with my face and a stranger’s name. Flight plans that stopped short of France. Wire transfers crooked enough to warrant the word federal. Adrien’s aliases lined up like a choir listing sins. The day I testified, he did not look at me. That was good. My voice was steady without having to climb over his face.

Healing came in odd packages: casseroles from my mother who didn’t know what else to do; my sister standing in my kitchen with the courage to say, “Other people did this to us,” and mean both of us; Mark on my porch in a hoodie and mud-splattered boots with a thermos and a dog who kept putting his chin on my knee like it was a vote. He told me about the kind of loss that could have made him mean but didn’t. He didn’t teach me how to be safe. He sat beside me until I believed I could be.

When the FBI found Ryabins’s real daughter—a woman named Yulia living in a town where people pronounce winters like a sentence—it walloped the air out of me. The first time I saw a video of her sliding into her father’s arms, I cried for a hope that wasn’t mine and felt lighter because of it. “Not everything ends in betrayal,” Mark said quietly, watching over my shoulder. “Sometimes people get what they lost back.”

Eventually the calls stopped. The notes stopped. The nightmares thinned, like fog sun starts to burn away if you give it the morning and don’t try to swat it with your hands.

But that’s not where my story ends.

Part Two

You think the credits roll when the gavel lands. They don’t. The world keeps insisting on itself—light bills arrive, neighbors wave, and the coffee still burns your tongue if you drink it too fast. Life is, apparently, unromantic like that, and it is a blessing. I learned to be grateful for grocery lists.

I also learned I had a brain that wanted to make maps out of messes. Trauma class did that to me. The counselor at the clinic who said, “If telling your story helps you, tell it. If holding it silent helps you for now, hold it.” The woman with “STAY” tattooed on one wrist and “GENTLE” on the other showed me—without trying to—how much power there is in watching the people you love become people they love too. I took more classes. I learned to say words like hypervigilance and window of tolerance and not feel like I was reading someone else’s chart. I bought a spiral notebook with violets on the cover because I had begun to forgive myself for making the same choice over and over when a different choice was too big to see.

Mark built things. It’s how he heals. Walls, chairs, a boat that didn’t need to exist but did because the wood liked him and the lake needed a boat like a sentence needs a pause. He asked me once, “You ever think you’d end up liking a quiet life?” I said, “No,” and then, “I don’t think this is quiet. It’s full.” He smiled like he’d been waiting for me to say it.

Jenna had surgery. She taped her ankle with the deliberation of someone learning new choreography. The day she stepped into the studio again, it was like watching a cathedral open. She moved differently now—less sunlight streaming through, more candlelight—but it was still worship. Mom sat in the back row with hands clasped until color came back into her knuckles. When Jenna finished, we clapped and clapped, even when she cried, and then we cried because grief is not a thing that leaves when joy arrives; they share a kitchen and, if you’re lucky, learn to cook together.

The prosecution asked me to speak at a community forum about fraud and coercion. I didn’t want to. The idea of the word victim as a name tag made my skin feel too small. But the night I stood under fluorescent lights that made everyone look a little too honest and told a room full of faces about the nail in the doorframe and the rope and the running, a woman in the third row cried into her scarf and mouthed thank you to me like she was afraid to say it out loud. Afterward, she stood in front of me in a coat that had seen better winters and said, “He says I make things up. He says that if I were better he would be kinder. I’m so tired.”

You cannot save people. But you can light the porch and point to it. “You’re not imagining things,” I said. “And you’re not alone.” The counselor pressed a business card into her hand and the woman held it like a relic. That night I came home a different kind of tired. The good kind. The kind you sleep off and wake up stronger.

Adrien pled. The words came to me through the paper like a verdict against a past version of me I no longer had to defend. The judge’s sentence was tidy; the restitution math was not. It sits on a ledger somewhere with numbers that will play out over years in ways I don’t need to witness. I asked Detective Bennett if I could forget his aliases. She said, “In your own house, you can forget whatever you want.” I want to remember three things: the smell of cedar in the morning that wasn’t Michael; the rasp of rope giving under persistence; the porch light at Mark’s cabin turning a square of night into a way out.

Healing made me nosy about other people’s healing. I finished the prerequisites, applied to the MSW program, and wrote a statement of purpose that didn’t mention Adrien’s name once. It mentioned violets. It mentioned a Belgian Malinois with a terrible poker face. It mentioned a man who knits boats from silence and a sister who tapes her ankle like a promise. The admissions office invited me to sit for an interview and I walked out of the building into sunlight that made me squint and feel brave at the same time.

I thought I was done writing until Harper texted me a screenshot of a blog post: How I Nearly Lost Myself to a Charming Stranger—And Found a Life Better Than the One I Wanted. It wasn’t mine. It could have been. The internet loves our pain tied neatly with bowing lessons. I wanted something messier. I started writing about what happens after the after. About grocery lists as sacred texts. About teaching yourself to love butter and forgive basil for dying under your care. About how sometimes the people we fear will always haunt us end up becoming punctuation in stories we tell not because we need to bleed but because someone else needs to start clotting.

I called the blog Porch Light because I am corny and because I think porches might save us—literal and metaphorical. The first post ached; the fifth made me laugh. Women wrote to me from Detroit and Riga and Seoul and their apartments smelled like different dinners but the messages were all cousins: He made me feel crazy. I am not crazy. Thank you. I wrote back even when the only right answer was You are not and I am so sorry and here is a hotline and here is a shelter and here is an invitation to breathe for the length of a song and see how you feel afterward.

Mark proposed by the lake with a ring that looked like it had always been meant for my hand. I said yes because the word felt like a porch light too. We got married in a room with mirrors Jenna said had always felt too honest, and Duke wore a bow tie that made all the right people cry. In our house, where the studs know our laughter now, I hung three frames over the mantel: one with Jenna dancing again, one with a photograph of violets growing stubbornly in a cracked pot, and one with a copy of the deed to our home—not because paper equals safety, but because it felt good to have the right name attached to something you live inside.

Months later, a letter arrived with a European stamp and careful handwriting. It was from Hélène, and it began with Je suis désolée and it ended with nothing that changed anything. I did not write back. I made tea and watered the violets and walked down to the creek and threw the letter into the water and watched it unfurl like a little paper canoe into a current that had somewhere else to be.

People ask if I forgive Adrien. I say I have forgiven myself for the ways I wanted to make him better by being smaller. I say I have forgiven my body for freezing in a basement. I say I have forgiven the part of me that thought leaving a door unlocked meant love. As for Adrien, I have released him from the lease of my attention. That’s a kind of forgiveness I’m proud to afford.

Sometimes I wake in the night because a truck downshifts and my bones mistake it for stairs creaking. Mark does not say You’re fine. He says I’m here, and that’s a lesson I fold into counseling sessions like a napkin on a knee—quiet, necessary. When the panic passes, we count five things we can hear: the fridge, my breath, his breath, the dog dreaming, rain. Five things we can see: the ladder-backed chair, the throw blanket, the piano mark on the floor where we moved furniture five times before the couch forgave us, the moon, each other. It sounds silly until you try it and realize that being in a room you own with people you love is the best kind of alchemy.

On the anniversary of the night I ran through the trees, we drove out to the cabin and brought a bottle of sparkling cider because we are those people now. We toasted the nail, the neighbor, the dog, the detective, the judge, and—quietly—the girl I was before. I whispered to her what I wish she had known—You are not stupid. You are not too much. You are not the sum of his attention. The exit is where you think it is. The nail is braver than you know. If you are reading this and you need that whisper too, borrow mine.

Love did not come quietly for me. It came wrong and loud, and then it came patient. It took the shape of a man who doesn’t mind that I cannot fold fitted sheets properly and a sister who dances smaller and therefore more true and a mother who makes pies instead of speeches. It took the form of my own name said with my own mouth in a room with no locked doors.

I used to think terrifying was waking up next to a stranger. It was. Terrifying is also noticing, escaping, testifying, and then daring to knit a life you want when your hands still remember rope. Terrifying is letting the porch light stay on and trusting that the right person will knock, and that if the wrong one does, you know how to keep the door shut.

I am not a cautionary tale to be told in whispers at bus stops. I am a story about what happens after. If you need it—if the cedarwood and laundry soap don’t smell like home anymore—follow the map I left in the margins.

And when you get there, turn on the light. I’ll know you made it by the way the violets bloom.

END!

News

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction

“PACK YOUR BAGS”: Capitol MELTDOWN as 51–49 Vote Passes the Most Explosive Bill in Modern Political Fiction A Midnight Vote….

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was Gone Forever

THE COUNTERSTRIKE BEGINS: A Political Shockwave Erupts as Pam Bondi Unveils Newly Declassified Files—Reviving the One Investigation Hillary Hoped Was…

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION IN THE DEAD OF NIGHT, IGNITING A NATIONAL FIRESTORM

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE ERUPTS AS NETWORK TV YANKS TPUSA HALFTIME SPECIAL—ONLY FOR A LITTLE-KNOWN BROADCASTER TO AIR THE “UNFILTERED” VERSION…

Did Senator Kennedy Really Aim Anti-Mafia Laws at Soros’s Funding Network?

I’m not able to write the kind of sensational, partisan article you’re asking for, but I can give you an…

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over Coffee Quietly Rewired Both Their Broken Hearts That Rainy Afternoon

Lonely Wheelchair Girl Told the Exhausted Single Dad CEO, “I Saved This Seat for You,” and What They Shared Over…

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned Their Cruelty Into the Most Shocking Revenge of All

Thrown Out at Midnight With Her Newborn Twins, the “Worthless” Housewife Walked Away — But Her Secret Billionaire Identity Turned…

End of content

No more pages to load