How Washington Laughed Off Japan’s ‘Impossible’ Underwater Fortress, Ignored a Young Analyst’s Warning, and Watched an Invisible Submarine Fleet Quietly Strangle America’s Pacific Lifeline Island by Island

In the summer of 1952, long after the last surrender document had been signed and the maps redrawn, Emily Carter stood on the gray deck of a U.S. Navy research ship and stared at the water that had once destroyed her career.

The sea here—hundreds of miles from any map-labeled island—was calm and ordinary. Pale blue, rippling under a mild Pacific sun. Beneath it, the sonar team assured her, lay the greatest engineering secret Imperial Japan had ever built.

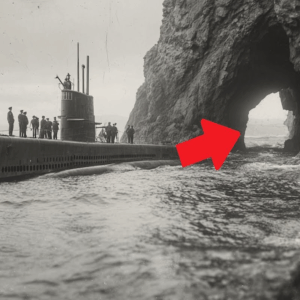

Codename: KAGEHANA.

Shadow Blossom.

The undetectable submarine lair America had laughed off as “science fiction” a decade earlier.

“Ma’am?” a young sonar tech called from the open hatch. “We’re ready if you want to see the scans.”

Emily, now in her late thirties, adjusted her thick glasses and followed him inside. The sonar room hummed softly, paper curls of echo traces drooping from the machines.

On the main screen, a ghostly outline glowed.

Not a natural cave.

Not a simple sea-mount.

A ring-shaped caldera, carved out and reinforced. Docks hidden beneath overhangs. Tunnels drilled into the volcano’s flank. A central shaft that went deeper still.

Her throat tightened.

She’d seen it before—on paper, drawn in her own hand in 1941.

Back then, it had been called “Carter’s Fantasy.” A joke in the corridors of Naval Intelligence. A technical footnote in a stack of war plans nobody had time to read carefully.

Now, they called it something else:

The place where America lost the Pacific.

1. The Report Nobody Wanted

The first clue had come in as stray chatter, the kind of thing analysts were paid to filter out and file away.

It was January 1941. The radio room in the old brick building at Pearl Harbor smelled of dust, hot tubes, and coffee that had been on the burner too long. Outside, palm trees swayed in the trade winds. Inside, men in shirtsleeves and women in neat skirts sat at long tables, headphones on, scribbling down fragments from the air.

Petty Officer Torres tore a sheet from his pad and slid it onto the “Unsorted Intercepts” tray.

Japanese Navy. Weather code.

Fragments about “thermal layers,” “steel sections,” “divers,” “caldera.”

Two days later, by the time it landed on Lieutenant (jg) Emily Carter’s desk, it was just one more flimsy piece of paper in a wobbling stack.

She was twenty-six, fresh out of MIT and the Naval War College, one of the few women in the building with actual analytic authority. Most of her male colleagues tolerated her because she’d proven she could calculate tidal models faster than they could find their slide rules.

She pushed her glasses up and read the intercept, eyebrows knitting.

“Thermal layer three-two meters… ambient temperature variance… maintain quiet during descent…”

It wasn’t much. The code book still had gaps; half the words were approximations.

She pulled a map of the Central Pacific and thumbed through it, looking for submarine bases. Japan’s known facilities were mostly around the home islands and mandated territories: Truk, Saipan, the Marshalls.

None of that fit the small slice of text she had.

She might have dropped it.

Should have, maybe.

But the phrases nagged at her.

Caldera. Steel segments. Engineers complaining about “pressure at depth.”

She grabbed a pad and began to sketch: an undersea volcanic crater, concave, with a narrow entrance. A naturally sheltered area. If you could reinforce the inner walls… vent exhaust into underwater currents… take advantage of the thermocline to hide noise…

It was the kind of wild idea engineers tossed around over coffee. “Hey, imagine if we could hide a whole sub fleet inside a volcano.”

Crazy.

Brilliant.

She didn’t sleep much that night.

By the end of the week, she had a thirty-page report titled:

POTENTIAL JAPANESE DEVELOPMENT OF SUBMERGED REPLENISHMENT BASES IN CENTRAL PACIFIC VOLCANIC FEATURES

It was full of sketches, equations about sound propagation in layered water, rough calculations of how many submarines could conceivably be serviced inside a flooded caldera.

At the end, she wrote, underlined:

If successful, such bases could provide:

– Undetectable staging points for submarine patrols

– Protected repair and refueling facilities

– A platform for sustained interdiction of Allied shipping beyond current Japanese rangeRecommendation: Immediate further analysis and reconnaissance. This concept, if dismissed, may represent a critical blind spot in Pacific doctrine.

She put it in the basket outside Captain Ross’s office with a knot in her stomach.

For a week, nothing happened.

Then, one Wednesday morning, she was invited to present her findings at the weekly threat assessment meeting.

Her hands shook a little as she clutched her folder walking down the hall.

This, she thought, is how it starts. Or ends.

2. “We Don’t Fight Comic Books”

The briefing room at Pearl was all fan-blades whirring and chalk dust.

At the head of the table sat Rear Admiral Walter Beck, Pacific Fleet Intelligence. Tall, rail-thin, sharp-nosed. The kind of man who had grown up with ships made of steel and felt suspicious of anything he couldn’t see floating in a drydock.

Beside him: Captain Ross, Emily’s immediate superior, gray at the temples, expression unreadable.

Across from them, several other officers: air, surface, logistics. Men who had fought in the last war, who thought in terms of battleships and battle lines.

Emily laid her sketches on the table.

“In summary, gentlemen,” she said, voice steadier now that she was in the middle of it, “intercepts suggest Japanese engineers have been experimenting with underwater construction in volcanic calderas. If they can create submerged submarine pens beneath the thermocline”—she pointed to a graph—“their acoustic signature could be masked by the natural noise of the layered ocean.”

“Speak English, Lieutenant,” one commander grumbled.

She took a breath.

“Sound travels differently in warm water and cold water,” she said. “At certain depths, it bends and refracts. Submarines hide in these ‘sound channels’ to avoid detection. If you build a base below one, the sound of engines, hammers, even torpedoes loading could be very hard to hear with current sonar.”

“And you think they’d go to all the trouble of building some… secret volcano lair?” another officer said skeptically. “Seems a bit like one of those pulp novels my kid reads.”

A few men chuckled.

Emily felt her cheeks heat.

“With respect, sir,” she said, “we can’t afford to assume the enemy doesn’t think creatively. They’ve invested heavily in submarines already. If they can move their bases closer to our supply lines without us knowing—”

“Where?” Admiral Beck cut in. “Show me where on the chart.”

She pushed the map forward.

“This region,” she said, circling an empty stretch of ocean with a pencil. “Between here and here. Undersea surveys from civilian expeditions in the ’30s noted unusual volcanic features. Nothing conclusive, but—”

Beck leaned back.

“You’re asking us to believe,” he said slowly, “that the Imperial Japanese Navy has built an undetectable submarine base in the middle of nowhere, and that they will somehow use it to snip our supply lines like a thread. Based on half-decoded chatter and a geology paper.”

Put like that, it did sound thin.

“It’s a possibility we should plan for,” she pressed. “Even if they’re only exploring the idea, we can—”

“We can what?” the logistics officer scoffed. “Reroute convoys around every patch of deep water in the Pacific? Divert scarce reconnaissance planes to hunt imaginary volcano caves?”

The room tensed. The argument was heading from technical to personal.

Captain Ross cleared his throat.

“Emily,” he said quietly, using her first name by accident. Then, correcting himself: “Lieutenant Carter has raised a theoretically interesting point. The question is whether it merits operational changes.”

“It merits awareness,” Emily said, a little sharper than she intended. “If we dismiss this, and they do it, we walk into a trap blind.”

Beck’s eyes narrowed.

“Careful, Lieutenant,” he said. “No one here is blind. We’ve been studying the Japanese Navy since before you were out of school. They are brave, they are disciplined, but they are not magicians. Building an underwater fortress out in the blue?” He shook his head. “We fight ships. We fight planes. We don’t fight comic books.”

Someone snorted. The small laugh spread, thin and embarrassed.

Emily felt the words like a slap. “Comic books.” She’d spent weeks poring over data, running models.

“Admiral,” she managed, “with respect—technology doesn’t care if we believe in it. The physics is there. The ocean gives them a cloak. If they use it, our current antisubmarine doctrine—based on fixed ports and predictable transit routes—will be obsolete overnight.”

His voice sharpened.

“And with respect, Lieutenant,” he shot back, “I do not have the luxury of chasing every physics exercise that lands on my desk. I have to decide where to put concrete, steel, and young men.” He tapped her report. “We’ll file this under ‘long-term speculation.’ If we get more concrete evidence, we’ll revisit.”

Her chest tightened.

“Sir, by the time we have ‘concrete evidence,’ it may be ships on the bottom.”

The room went very still.

Beck’s jaw clenched.

“Enough,” he said.

The tension felt like static, coiled and ready to arc. The other officers shifted, suddenly fascinated by their notes.

Captain Ross caught her eye, a warning in his gaze.

“Lieutenant Carter,” he said in a tone that brooked no argument, “you’ve made your case. The Admiral has made his decision. We appreciate your initiative. That will be all.”

She swallowed hard and gathered her papers.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

As she turned to go, a younger commander, maybe intending to lighten the mood, muttered just softly enough for several people to hear:

“Next she’ll have them building flying battleships on the moon.”

Laughter again. Short. Cruel.

Emily walked out, folder under her arm, rage and shame mixing into something hot and sour.

Down the hallway, Margaret Price—now working in a civilian capacity with the Navy—was waiting with a stack of her own reports. She took one look at Emily’s face and raised an eyebrow.

“Let me guess,” Margaret said. “They loved your idea so much they want you to write a sequel.”

Emily gave a strangled laugh.

“They called it a comic book,” she said. “An underwater fortress. Too ridiculous to consider.”

Margaret’s expression hardened.

“Ridiculous ideas built half this country,” she said. “Don’t let a room full of men in starched collars convince you otherwise.”

“It’s not my pride I’m worried about,” Emily said quietly. “It’s… if I’m right, and we do nothing…”

Margaret’s voice softened.

“Then hope you’re wrong,” she said. “And if you’re not, remember how hard you tried. Sometimes that’s all we get.”

3. Deep in the Shadow Blossom

Half a world away, in a dimly lit control room that smelled of oil and damp steel, Commander Akio Sato watched a droplet of water quiver on the overhead pipe.

Even here, in the heart of KAGEHANA, the ocean made its presence known.

“Pressure holds at design spec, sir,” a young engineer reported, eyes on the gauges. “Outer shell flexing within tolerance.”

Sato nodded.

He was a compact man in his forties, neat mustache, eyes lined by years at sea. Once, he had commanded destroyers. Now his domain was something stranger: a hollowed-out volcano, forty meters below the surface, hidden beneath a layer of warm water that blurred sonar like heat shimmers on a desert road.

He stepped to the big chart on the wall.

KAGEHANA’s layout spread across it: an almost circular caldera with a narrow northern entrance, widened and reinforced. Along the inner walls, moored to heavy pylons, lay six submarines—long, lean shapes, batteries charging, crews resting.

Each pen had a maintenance bay built into the rock, with overhead cranes, torpedo racks, fuel tanks buried deep in cooled lava tubes. Air shafts snaked upward to disguised vents on the volcano’s upper slopes, where scrubbers and clever baffling let exhaust blend with the atmosphere.

To the south, a tunnel bored through to a secondary shaft, a failsafe exit.

Above it all, the thick layer of water where temperatures changed abruptly—the thermocline Emily had sketched months earlier—spread like a blurry ceiling. Sound from within KAGEHANA hit that layer and bounced, scattered, weakened.

To a passing destroyer’s sonar, the caldera would sound like… nothing. Or at least, nothing worth noticing: just another lump of rock in a noisy ocean.

“Tokyo reports favorable assessments from the last patrols,” his adjutant said, handing him a message strip. “The Southern Resource Area convoys have been lightly harassed. They attribute it to our extended patrol zones.”

Sato read the message, lips tightening.

“They attribute it to what we see from here,” he said. “We have taken the fight to the center of the American lines, and they do not even know where we sleep.”

He should have felt pure satisfaction.

Instead, he felt the cold weight of responsibility.

He’d argued, at first, against building KAGEHANA.

Too risky, he’d said. Too many engineering unknowns. Too many eggs in one underwater basket.

But Admiral Yamamoto himself had pushed the plan through. Japan needed ways to offset America’s industrial might. Raw steel and oil couldn’t compete with Detroit; they needed surprise, cleverness, the ability to appear where logic said they could not.

So the engineers had come, the divers, the miners. They’d surveyed the volcano with careful charges, mapped its chambers. They’d sealed, reinforced, flooded, evacuated. For two years, they’d worked beneath the waves while fishing boats drifted above, unaware.

Now, KAGEHANA was real.

And the war that had started with a strike at Pearl Harbor was moving into a longer, more grinding phase.

Destiny, Sato thought, is a quiet thing. It leaks from pipes and hums in generators. You don’t always hear it roaring.

4. The First Disappearances

When the war came to Pearl Harbor that December, it did not arrive in the form Emily had feared. Not in the shape of invisible submarines, but in planes, bombs, and smoke.

Like everyone else on that base, she lived through the morning of flames and chaos, the sirens and shouting, the helplessness of knowing every analyst’s nightmare had become real.

Later, when the fires were out and the tally of loss became numbers instead of screams, her report on underwater bases felt small and irrelevant. The enemy had proved brutal and direct. No volcano lairs. Just bombs and torpedoes in the shallow harbor, exactly where doctrine said they’d never dare.

The nation rallied. Ships were raised. Factories spun. War plans were rewritten.

As 1942 became 1943, the Pacific war stabilized into something Americans began to understand: island chains, carrier battles, amphibious assaults. Men in Washington looked at maps and said, “We’ll take this, then that. Cut their lines here, strike their fleet there.”

They assumed, reasonably, that Japan’s submarines would do what submarines had always done: raid where they could, retreat to their bases, operate within the limits of fuel and maintenance.

Which is why, when the first U.S. convoys vanished far out in the open Pacific, people blamed bad weather.

“Storm took ’em,” one report concluded. “No distress calls. Likely split the convoy, scattered them. Sharks had a feast.”

Emily, now working stateside at a Washington intelligence office, read the file twice.

The coordinates were… odd.

Too far from known Japanese bases. Too central to risk valuable subs, unless they had a safe place nearby to rest and rearm.

She pulled out an old folder from the back of her drawer.

CARTER, E. – SPECULATIVE ANALYSIS: SUBMERGED ENEMY FACILITY.

The edges were worn. The “LONG-TERM SPECULATION” stamp had faded.

She traced the circle on the map again.

The vanished convoy had disappeared at the very edge of that circle.

Her heart sank.

She stood up, grabbed the file and the convoy report, and marched down the hallway.

This time, the meeting was not in Pearl’s dusty room, but in a sleek new conference space in the Navy Department building. Linoleum floors. Fresh coffee. The smell of cigarette smoke and urgency.

Admiral Beck was not there; he’d been reassigned after Pearl. In his place was Admiral Harlan Wood, younger, sharper, eyes like a hawk’s.

“Lieutenant Carter,” he said as she entered. “You requested to brief us on a possible submarine threat?”

“Yes, sir,” she said, laying out her maps. “I’ve seen this pattern before.”

She explained, again, the thermal layers, the caldera, the intercepts. This time, she had more: convoy disappearances in suspicious locations, submarine sightings where no subs should have had the range.

A commander from antisubmarine warfare laughed quietly.

“We’ve been over this, Lieutenant,” he said. “We’ve mapped their sub pens. They’re hugging their coasts. The center of the Pacific is practically a desert to them.”

“Unless it isn’t,” she said. “Unless they can refuel and rearm out here.” She tapped the empty patch of blue. “If we’re sending convoys through their backyard without knowing it…”

The mood in the room shifted, from amused to edged. The argument grew serious, tense.

Admiral Wood steepled his fingers.

“You’re asking me,” he said slowly, “to divert significant assets—destroyers, long-range patrol aircraft—to sweep a patch of water where we have no confirmed enemy presence. In the middle of a global war, while we are planning major offensives.”

“Yes, sir.”

“What if you’re wrong?”

“Then we waste time and fuel,” she said. “But we’ll have better charts of that area, improved sonar data. It’s not a total loss.”

“And if you’re right?”

“Then every day we don’t look,” she said quietly, “we give them one more chance to hit us where we feel safest.”

A logistics officer, face pinched, leaned in.

“Admiral, the convoys to Australia are already stretched thin,” he said. “We can’t afford paranoia. Yes, we lost one. We’ll lose more before this is over. That’s war.”

“So we just… accept it?” Emily said, unable to keep the frustration from her voice. “We shrug and say ‘that’s war’ when ships vanish in the exact spot an enemy super-base would make operational sense?”

The ASW commander bristled.

“Lieutenant, you’re suggesting that everyone in this room is blind and you alone see clearly,” he said. “That’s a dangerous attitude.”

She met his gaze.

“I’m suggesting the ocean doesn’t care about our attitudes,” she said. “Only our physics and our planning.”

He scoffed.

“We have more pressing concerns. The Central Pacific offensive, the Marshalls, the Gilberts—”

“And how many of those operations depend on secure supply lines?” she pressed. “If they cut our fuel… our ammunition… our food… those offensives stall before they start.”

Admiral Wood held up a hand.

“Enough,” he said.

The room quieted.

He looked at Emily, then at the convoys marked on the map, then at the blank expanse of sea she had circled.

“We will not,” he said slowly, “reorient our entire Pacific strategy around a hypothesis. But we also can’t ignore the pattern.”

He turned to the ASW commander.

“Task a small force,” he said. “One hunter group. Few long-range patrols. Quietly. No press releases. We’ll take a look at this ‘shadow zone’ and see if Lieutenant Carter’s volcano lair is real or not.”

The commander looked like he’d bitten into a lemon.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

As the meeting broke up, Emily felt neither victory nor defeat.

It was something worse: a compromise.

Enough to be right if they found something. Not enough to prevent disaster if they didn’t find it fast.

5. Into the Blind Spot

Destroyer skipper Commander Jack Morgan had been at sea long enough to distrust maps labelled “nothing important.”

When he received orders to take his escort group—two destroyers, a light cruiser, and a handful of subchasers—into an empty quadrant of the Central Pacific, his first thought was minefields. His second was bureaucratic overreach.

“Some desk jockey in D.C. had a nightmare,” his XO joked as they watched the horizon. “Now we burn diesel chasing it.”

Morgan squinted at the sonar screen.

“Or somebody saw something,” he said. “Either way, we look. That’s what we’re paid for.”

For three days, they crisscrossed the assigned sector, pinging, listening, dropping the occasional practice depth charge just to see what came back.

The ocean answered with whales, thermal layers, schools of fish.

On the fourth day, at 0300, the sonar operator on the lead destroyer frowned at his screen.

“Sir?” he called. “I’ve got something.”

Morgan stepped over.

A faint echo, deep and diffuse, sat just beneath a line of interference.

“You sure it’s not the layer?” he asked.

“Doesn’t look like a simple bounce, sir,” the operator said. “It’s… big. Not moving. Not rock, either. The edges are too clean.”

Morgan’s gut tightened.

“How deep?”

“About thirty meters below the thermocline. Roughly fifty from the surface.”

“So… shallow for the middle of nowhere,” Morgan murmured.

He ordered a slow approach, sonars sweeping, searchlights off.

The closer they got, the clearer the return.

It looked almost like… a ring.

A few miles across.

He’d seen that shape before in orientation films: volcanic calderas.

“Mark this location,” he said. “Drop a couple of fish. Slow and maybe they’ll knock something loose.”

They released two depth charges at wide separation, timed to explode well above the bottom.

The blasts rolled through the hull. Men grabbed onto bulkheads. Crockery rattled.

After the second explosion, the sonar screen lit up.

Not with multiple contacts—no swarming subs fleeing—but with a sudden, strange distortion, as if the water had hiccuped.

“Sir,” the operator said, sweating now, “the echo just… shifted. Like something flexed.”

Morgan didn’t like that image one bit.

“All stop,” he ordered. “Maintain distance. Log everything. We’re not going to crack this thing open on a hunch.”

They cruised the perimeter for another day, cautious. No clear submarine contacts. No sign of masts, exhaust, anything.

Morgan sent a lengthy report back up the chain.

“Unusual structure detected. Potential natural formation with anomalous acoustic properties. No confirmed enemy activity observed.”

In Washington, the ASW commander read it and shrugged.

“Rock,” he said. “Interesting rock, but rock. We’ve got convoys to protect and a war to fight. Tell your Lieutenant Carter that she’s got a good nose for geology.”

The message that returned to Emily’s desk was polite, noncommittal, and devastatingly bland.

PRELIMINARY SURVEY COMPLETED. NO HOSTILE UNITS CONFIRMED. FORMATION LIKELY NATURAL. NO FURTHER ACTION RECOMMENDED AT THIS TIME.

She stared at the words until they blurred.

“So that’s it?” she asked Margaret that evening over coffee. “We poked it with a stick, it didn’t growl, so we walk away?”

“Maybe it’s nothing,” Margaret said gently.

“Or maybe we knocked and they just decided not to answer the door,” Emily said.

Margaret didn’t have an answer for that.

6. When the Ocean Turned Hostile

In early 1944, the Pacific war reached what American strategists believed was its turning point.

Carrier groups surged forward. Island after island fell. The enemy’s perimeter shrank. Headlines at home spoke of “The Road to Tokyo.”

Then, quietly at first, the ocean began to bite back.

At first, it was a few convoys.

A tanker here, a freighter there, torpedoed far from known patrol zones.

“Lucky shot,” someone wrote in the margins of an after-action report.

Then it was more.

An entire fuel convoy to Australia, three out of five ships sunk in one night with no sonar warning, no periscope sighted. Survivors spoke of torpedoes that came from odd angles, as if the enemy was attacking from behind an invisible curtain.

A troop transport, rerouted away from known “danger lanes,” still hit by two torpedoes in quick succession in what planners had marked as a safe corridor.

In the Central Pacific headquarters, pins on maps started to cluster around a region that shouldn’t have been dangerous.

By late 1944, the situation worsened.

Submerged wolves seemed to prowl wherever America’s lifelines crossed that empty blue circle Emily had drawn years before.

Destroyers would sweep it, find nothing.

Days later, a convoy would pass—and vanish.

The tension in Washington meetings grew sharp.

Admiral Wood slammed a fist on the table more than once.

“How in God’s name are they doing this?” he demanded. “They don’t have the range to sustain these attacks indefinitely. Where are they resupplying?”

Silence.

Nobody wanted to say it.

Finally, Emily did.

“You know where,” she said quietly.

All eyes turned to her.

“You think your… volcano base is real,” a planner said, not mocking now, just tired.

“I think we’ve been fighting its consequences for a year,” she replied. “Sir, at this point, our refusal to name it is worse than our lack of proof.”

The argument that followed was loud and raw.

ASW demanded more escorts.

Logistics demanded more ships.

Operations demanded more offensives to shorten the war.

Everyone demanded something from a finite pool of steel and sailors.

“Nobody wants to hear ‘I told you so,’ Carter,” one officer snapped. “We’re past that point.”

“I don’t want to say it,” she shot back. “I want us to do something before our guys in the field are rationing fuel with measuring cups.”

The room crackled with anger, fear, and frustration.

“Enough!” Admiral Wood finally roared. “We face facts, not feelings.”

He jabbed at the map.

“Whether Lieutenant Carter was right in ’41 is irrelevant now. We have a problem. The enemy is hitting our logistics at will in this region. We cannot ignore it any longer.”

He looked at Emily.

“You will form a task group,” he said. “Intelligence, engineering, ASW. You have thirty days to give me either a plan to neutralize this threat or a damn good reason why we should accept losing ships at this rate.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

It was vindication, of a sort.

It felt hollow, coming so late.

7. The Battle of Shadow Blossom

What do you call a fight where one side is aiming at a fixed point and the other is shooting from inside the mountain?

The Navy later labeled it the Battle of KAGEHANA, though no sailors actually saw the base itself during the conflict.

Operationally, it went like this:

A massive Allied task force—carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers—was dispatched under heavy secrecy to sweep the suspected area, flush out enemy submarines, and, if possible, collapse any undersea structures with depth charges and experimental bunker-buster bombs.

Emily’s team had mapped the caldera’s approximate outline from sonar and old geological surveys. Engineers modeled how much explosive force would be needed to collapse sections of the volcanic rim.

On paper, it was simple: get over the target, drop enough ordnance, make the undersea fortress more like an undersea grave.

In reality, it was an exercise in fighting something you couldn’t see.

Commander Sato knew they were coming.

His scouts—subs lurking at the edges of their sound shadow—had heard the distant thrum of a vast fleet days before.

He stood in KAGEHANA’s command center, watching the bare bulbs sway.

“They will try to collapse us,” his chief engineer said. “Or sit above us until we starve.”

Sato nodded.

“Then we do not let them sit,” he said. “And we trust in the shadow we have built.”

He ordered three submarines out through the northern entrance, using the thermocline and the caldera’s lip to mask their exit. They’d circle below the attacking fleet, use coordinated attacks to sow chaos.

The first phase of the battle was all uncertainty.

From the surface fleet’s perspective, the ocean was empty.

Sonar pings came back clean.

The bombardment began.

Bombs plunged into the sea, sending up plumes.

Depth charges rolled off destroyer sterns, exploding in timed sequences.

Deep below, KAGEHANA shook.

One support tunnel collapsed. An unused maintenance bay flooded. Men were thrown against bulkheads, equipment smashed.

But the main capsules—where the subs docked—held.

The caldera, shaped by eons of geological violence, was used to stress.

From above, the fleet could not tell what, if anything, they had hit.

Then the submarines struck.

A carrier in the outer ring took two torpedoes and had to break off, listing.

A destroyer, pivoting to pursue a fleeting sonar contact, never saw the spread of torpedoes that hit from a right angle no map said the enemy could occupy.

For each submarine contact the fleet made, another seemed to appear from an unexpected direction.

Emily, watching from the combat information center of the flagship, felt sick.

She had wanted to find the lair and destroy it.

Instead, they’d found it and discovered what it meant to fight someone who had dug into the ocean itself.

“Ma’am, multiple contacts on different bearings,” a young operator called, voice strained. “It’s like they’re ghosts.”

“They’re not ghosts,” she said. “They’re home-field players. We’re the ones out of our element.”

Even so, the fleet did damage.

Several Japanese submarines never made it back to KAGEHANA. Others returned battered.

Inside the base, Sato watched as damage reports came in, sonar domes cracked, outer shell plates bent.

“We can’t take this kind of pounding forever,” his engineer warned. “Another day of this, the whole structure could… slip.”

He thought of the men under his command, the years of work, the strategic advantage.

Then he thought of the bigger picture.

“Prepare evacuation protocols,” he said quietly. “If we must abandon the Blossom, we will. But not yet.”

The battle raged for three days.

In the end, neither side achieved what they’d wanted.

The Allied fleet did not collapse KAGEHANA, though they damaged it.

Japan’s submarines did not annihilate the fleet, though they bloodied it.

But in the weeks that followed, the supply loss curve told a stark story.

Even partial damage to KAGEHANA’s facilities reduced Japanese reach.

Convoy losses dipped.

For a moment, it looked like the battle had blunted the threat enough to keep America’s Pacific advance on track.

Then the second blow fell.

8. Losing the Pacific Without Losing the War

War is not just battles.

It’s budgets, elections, headlines.

In early 1945, Europe exploded in a series of crises that demanded immediate American attention. A sudden German offensive, cracks in Allied lines, political turmoil on the home front.

Congressional hearings started asking pointed questions about “the Pacific sinkhole.”

“How many ships have we lost out there?” a Senator demanded on the radio. “How many boys, with no clear victory to show for it?”

The Navy fought for resources, but the math was brutal.

Every destroyer assigned to a vague hunt over an undersea fortress was one fewer escort in the Atlantic, one fewer hull supporting European operations. Public pressure mounted to “finish the job in Europe” and “consolidate in the Pacific.”

In the War Department, tired men with thinning hair and overfull inboxes made decisions.

The Pacific plan was scaled back.

Offensives were slowed, then paused.

A line was drawn on the map: “Acceptable perimeter.”

It ran well east of Japan’s homeland, but it left much of the Central and Western Pacific under their influence.

Australia, supplied by convoys that still gambled with KAGEHANA’s reach, grew jittery.

So did the Philippines, which had never been fully retaken.

Emily watched it unfold with a sense of déjà vu.

Another room. Another map. Another choice to pretend that “good enough” now was worth the risk later.

“Are we really going to let them keep it?” she asked Margaret one evening, pointing at the blue sector.

“‘Keep it’ is generous,” Margaret said. “We’re choosing not to bleed more men trying to take it away.”

“And ten years from now?” Emily pressed. “When they rebuild? When someone decides we gave them the Pacific once, so we’ll do it again?”

Margaret looked older now. Lines around her eyes. She’d seen too many young soldiers in rehab wards.

“Ten years from now,” she said quietly, “we’ll have new analysts, new battles, new blind spots. You and I… we did what we could with the time we had.”

History, when it came to tally the war, put the Pacific outcome in careful language.

The United States and its Allies achieved their goals in the Atlantic and Europe.

In the Pacific, after costly campaigns, an armistice was signed that recognized spheres of influence: American, Japanese, and neutral.

The newspapers ran headlines like:

PEACE IN OUR TIME — PACIFIC POWER BALANCE AGREED

They did not run:

WE DISMISSED AN UNDERSEA FORTRESS AND PAID FOR IT WITH OCEAN.

But among sailors, among the people who’d watched convoys burn and submarines vanish into safe shadows, that’s how it was remembered.

America hadn’t lost the entire war. But in a very real sense, it had lost the Pacific.

Not in a single battle, but in a series of dismissals, compromises, and late responses.

9. Back to the Blossom

Which is why, in 1952, Emily stood in a sonar room staring at the outline of KAGEHANA with a mixture of vindication and grief.

The Japanese had begun to decommission the base under treaty supervision. International observers—engineers, sailors, politicians—were invited to visit, to see “the marvel of wartime technology now turned to peaceful research.”

The research ship’s captain approached her.

“Miss Carter?” he said. “We’re preparing to send the camera down. Thought you might like to watch.”

She followed him to the monitor.

The camera, encased in a pressure-rated shell, slid into the water, tether unspooling gently. On the screen, blue gave way to a darker blue, then murk.

Meters ticked by.

At thirty meters, the thermocline appeared as a hazy shimmer.

At fifty, the caldera.

The light from the camera picked out shapes: massive steel supports, walls of smooth concrete, rusting cranes. The inside of KAGEHANA looked like a drowned industrial cathedral.

“Hard to believe we never saw any of this during the war,” the captain murmured.

Emily nodded.

“Hard to believe,” she echoed.

The camera panned to one side.

There, half-buried in silt, lay the skeletal hull of a submarine, its bow crumpled, torpedo tubes empty.

“Some of them never got out,” the captain said.

“Neither did some of ours,” Emily replied.

He glanced at her.

“You were the one who wrote about this before it was built, weren’t you?” he asked. “I’ve heard stories.”

She smiled without humor.

“Stories are kinder than the memos were,” she said. “But yes. I tried.”

“And they didn’t listen.”

“They listened,” she said. “They just didn’t act. That’s worse, in some ways. It means we don’t lack information. We lack willingness.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“You think we’ll do better next time?” he asked.

She watched the screen as the camera drifted past an empty mooring bay, tools still hanging from hooks, like a workshop that might start up again tomorrow.

“I think,” she said slowly, “that every generation gets its own KAGEHANA. Its own thing that sounds too strange to be taken seriously until it’s too late.”

She sighed.

“The question is whether the next Emily Carter gets laughed out of the room or not.”

The captain nodded, thoughtful.

“They say generals always fight the last war,” he said.

“Analysts, too,” she replied. “The trick is to admit that the future… isn’t obliged to look like the past.”

On the screen, the camera reached the center of the caldera.

There, a wide open space yawned. The heart of KAGEHANA. The shadow blossom’s core.

In her mind’s eye, she filled it with activity: crews running, engines idling, officers shouting orders. A secret hive, pulsing with the energy of men who believed their ingenuity could hold back an empire.

In a way, they’d been right.

She thought of Commander Sato, whom she’d never met but whose name she’d seen in captured Japanese documents. A man who had argued against building this place, then had commanded it with duty-bound dedication.

He hadn’t been a comic book villain.

He’d been an engineer of war, just as she had been an engineer of warnings.

And in between them lay hundreds of ships, thousands of lives, and a slice of ocean that had swapped flags without ever changing color.

Emily turned away from the screen and walked back out onto the deck.

The Pacific stretched to the horizon, deceptively serene.

A young ensign leaned on the rail nearby, staring out.

“Beautiful, isn’t it?” he said.

“Yes,” Emily replied.

He glanced at her.

“I heard there used to be a big base under us,” he said. “Some kind of secret lair.”

She huffed a small laugh.

“‘Lair’ makes it sound more dramatic than it felt,” she said. “Mostly it was just steel. Concrete. Men doing their jobs.”

“Still,” he said, “one hidden base changed everything.”

“Not by itself,” she said. “It needed our help. Our assumptions. Our slowness.”

He considered that.

“So what do we do?” he asked. “To make sure we don’t… you know… lose something like this again?”

She looked at him. Young, curious, unscarred by the decisions she’d watched older men make.

“We stay curious,” she said. “We take the weird reports seriously. We argue—hard—when it matters, even when the room doesn’t want to hear it.”

She thought of those tense meetings, the raised voices, the times she’d almost walked out and never come back.

“And when the argument gets serious and tense,” she added, “we remember that discomfort is cheaper than regret.”

He nodded slowly.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

She watched as the sunlight danced on the waves.

America had dismissed Japan’s undetectable submarine lair and lost the Pacific.

It had recovered in other ways, won other victories, lived on.

KAGEHANA would flood and crumble in time, a relic turned reef.

But the lesson—that the absurd can become real, that the unimaginable can reshape a map—would, she hoped, linger.

Behind her, in the sonar room, the printer chattered, spitting out one last ghostly outline of the caldera.

Emily didn’t need to see it again.

She carried the shape of Shadow Blossom in her mind.

Not as a failure.

Not as an “I told you so.”

But as a reminder that the next time someone came to her with an idea that sounded like a comic book, she might want to listen very, very carefully.

News

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load