How One Gunner’s “Backwards Setup” Turned His Sherman Into a Sniper Tank — And Destroyed Everything…

December 3rd, 1944. The Herkin Forest. It’s cold, bone cold. The kind of cold that settles in your joints and doesn’t leave. The trees are bare, their black silhouettes clawing at a sky the color of dirty ash. Fog hangs low like a ghost refusing to lift. Somewhere in the distance, artillery thumps with a steady rhythm like a giant heartbeat. Inside an M4 Sherman tank parked behind a shattered brick wall, a young gunner named Harlon Vickery leans into the eyepiece of his 75 mm cannon.

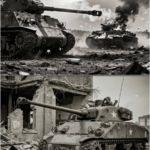

The tank’s turret is not facing forward. It’s turned 180°, pointing backwards. His loader looks at him sideways and mutters, “You’re really doing this backwards setup thing, huh?” Harlon doesn’t answer. His breath fogs the glass. His fingers tighten around the firing mechanism. He’s quiet, still listening. Then through the mist, a shape emerges. It’s a Panther tank, German, heavy, lethal. It’s flanked by two more, rolling slowly down a muddy path like they own the forest. Harlon exhales, one shot.

The 75 mm round punches through the morning stillness, and a second later, the lead panther erupts in flying. The other two tanks hesitate, confused. They weren’t expecting a shot from behind a collapsed farmhouse. They weren’t expecting a Sherman, and they sure as hell weren’t expecting a Sherman to be sniping at long range. Inside the turret, the loader gasps. The commander shouts, “Holy hell, Vicory, you hit him clean. ” But Harland Vicory doesn’t celebrate. He’s already adjusting the turret, tracking the second tank.

Because this isn’t just luck, this is strategy. This is what happens when a farm boy from Kentucky rewrites the rules of armored warfare by turning his Sherman backwards and turning himself into a one-man sniper team. They laughed at him. They said it would never work until it did. And when the smoke finally cleared, the Germans weren’t the only ones surprised. the gunner no one expected. Before he became the man who stunned a German tank column in the heart of the Herkin Forest, Harlon Vicky was just another quiet kid from Whitley County, Kentucky.

He wasn’t tall. He wasn’t loud. He didn’t grow up around tanks or even cars. He grew up fixing tractors. His father ran a small farm. His mother was a school teacher and like so many young men after Pearl Harbor, Harlon enlisted in the United States Army because he felt it was the right thing to do. He never imagined he would end up in a Sherman tank, let alone commanding its gun in one of the deadliest forests in Europe.

Harland trained at Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he was assigned to the Armored Division. His instructors noted he had steady hands, sharp eyes, and a quiet way of thinking through problems that most recruits didn’t. While others fired by instinct, Harlon did math in his head. He measured distance. He watched wind. He calculated. Still, no one noticed him. He wasn’t the fastest. He wasn’t the loudest. And in a war where big personalities often rose to the top, Harland stayed in the shadows until he got to Europe.

By the time his unit landed in France in August 1944, the war had shifted. The Americans had broken out of Normandy. The Allies were pushing east, driving the Germans back toward their own border. But now came the hard part. Pushing through terrain that heavily favored defense, hills, dense forests, narrow roads, ambush country. That’s where the M4 Sherman tank came in. The M4 was America’s main battle tank. More than 49,000 of them were built during the war, making it one of the most produced tanks in history.

But the Sherman had problems, serious ones. Its 75 mm gun struggled to penetrate German armor at long range. Its armor was thin compared to the German Panther and Tiger tanks. In direct combat, Shermans were often outgunned and outmatched. Soldiers joked that it was a Ronson, named after the cigarette lighter, because it lit up the first time, every time. Still, the Sherman had advantages. It was fast, easy to repair, and when used smartly, especially in coordinated groups, it could overwhelm the enemy.

But it required tactics, and it required soldiers willing to think differently. That’s where Harland came in. After two months of skirmishes and close calls, his tank crew had developed a bond. His commander was Staff Sergeant Jean Corbin, a loudtalking Chicago native who didn’t much care for theory. “Keep it simple,” Corbin used to say. “Drive, shoot, survive.” But Harlon was starting to think survival wasn’t going to come from driving and shooting. It was going to come from surprise, from thinking like the enemy, from doing something no one else dared to do.

So one night while cleaning the gun after a long day’s patrol, Harlon brought it up. What if? He asked, we set up the Sherman in reverse. The loader, Private First Class Mike Rizzo, laughed. You mean shoot backwards? No, Harlon said, “I mean, park it facing away from the road. Rotate the turret 180 degrees. Use the rear to face the enemy. That way, we can back into a position, fire, and pull forward to retreat. We lower our profile, stay hidden, and we can strike first.” Corbin stared at him for a long moment, then shook his head.

That’s the dumbest damn thing I’ve heard all day, he said. But Haron wasn’t joking. He was already planning how to make it work. Rejection, trial, and a bullet through the fog. At first, no one took Harlland seriously. The idea of turning the turret backwards, of using a Sherman tank, like a sniper rifle, was laughable to most of the crew. They called it hillbilly logic. They said he was trying to fight tanks like a squirrel hunts deer, sitting still and waiting for something too big to miss.

Sergeant Corbin, the tank commander, made it clear this isn’t the kind of war where you get to sit back and aim pretty. You see a panther, you shoot fast, or you’re dead faster. But Harland didn’t back down. He kept thinking, kept drawing sketches, kept running math in his notebook, elevation angles, shell drop over distance, estimated armor thickness at oblique angles. He studied the capabilities of the 75 mm M3 gun on the Sherman, especially when firing the high velocity armor-piercing rounds known as HVAP.

These rounds could penetrate up to 120 mm of armor at 500 yd, but their effectiveness dropped sharply with distance. If he was going to snipe, he had to choose his angles perfectly. So he looked for cover, for high ground, for tree lines, for clearings where German tanks might cross in single file, unaware of a Sherman hidden in the woods. turret pointed like a coiled snake. Still no one approved his setup until one afternoon in mid- November. The forest was soaked from days of rain.

Mud clung to boots like quicksand. The unit had been shelled every morning for a week. The men were exhausted, cold, and constantly on edge. That day, a nearby tank crew had been ambushed while turning a corner near the village of Vosanak. One Sherman took a direct hit from a panzer force at close range, blew the turret clean off. There was nothing left to bury. That night, Harlon made his move. He asked Rizzo, the loader, to help him run a private test.

They snuck out early the next morning during a patrol assignment. Instead of taking the usual forward position, Harlon had them pull back into a patch of trees overlooking a small field, the kind the Germans often used to reposition armor. He rotated the turret backwards, adjusted elevation, and waited. Nothing happened for hours, just wind, rain, and the occasional crack of small arms fire in the distance. But then through the fog, movement. Not tanks, just a pair of German motorcycles scouting.

Still, Harland tracked them through the gunsite, following their lazy arc across the clearing. He didn’t fire. It wasn’t worth revealing the position, but something clicked. The shot was there. He could have taken it. They returned to camp without incident. Corbin scolded him for deviating from orders, but Harland didn’t argue. He knew what he’d seen. He knew it could work. The next day, everything changed. A single German tank, most likely a lone panther, was spotted near the ridge just west of Schmidt.

It had been harassing supply lines, firing from long distance and disappearing before American units could respond. Artillery couldn’t pin it down. Air support wasn’t available. So Corbin, half joking, turned to Harlon. You still think that squirrel tactic of yours works? Harlon nodded. Then get up there and prove it. They gave him one shot, one chance. Harland chose a position near a clearing off the call trail, a muddy, narrow road used by both American infantry and armor to reach Schmidt.

He reversed the Sherman into the brush, turret facing out, and waited. The fog rolled in thick. Visibility dropped to less than 100 yards. And then it happened. A panther rolled into view. Just the tip of the turret slicing through the fog like a shark’s fin. Harlon didn’t wait for it to clear fully. He adjusted, took a breath, and fired. The 75 mm round screamed through the trees and struck true. The explosion lit up the fog like lightning.

Flames licked upward. A German crewman scrambled out, trailing smoke. Then another, then silence. The kill was confirmed. Long range, first shot, turret backwards. No one laughed anymore. That one shot didn’t just take out a tank. It rewrote what a Sherman could be. And for Harland Victory, it was only the beginning. Forest death traps and a plan set in motion. The Herkin Forest wasn’t just a battlefield. It was a meat grinder stretching across 50 square miles of dense, tangled woods near the German border.

It was where American dreams of a quick victory went to die. Fog, mines, artillery so constant it became part of the air. More than 33,000 American casualties would be recorded in that forest, more than at the Battle of the Bulge. And in November of 1944, Harlon Vickery and his crew were thrown right into it. Orders came down, hold the call trail, and push toward the town of Schmidt. It was a narrow road, little more than a muddy scar winding through ravines and hills.

The enemy had the high ground. Trees were wired with booby traps. German 88 mm guns were zeroed in on the trails bends, and somewhere out there, the remaining Panthers and jogged ponzers waited like wolves in the fog. It was hell on earth. Every corner, Harlon would later write in a letter home, felt like a death sentence. You didn’t know if the next step would be mud or a mine. Their Sherman C113 was battered but operational. Corbin was tense, always checking maps.

Rizzo, the loader, stopped cracking jokes. And Harlon, he grew silent, focused. He wasn’t afraid. He was preparing because this time he had a plan. The success of his backward shot wasn’t luck. He’d studied the terrain, calculated the shot, chosen his angle with intent. Now he wanted to push the tactic further. Not just one ambush, but a full sniper setup. His idea was to find a bottleneck, a spot where German tanks would have to slow down, turn, or expose their flanks.

He found it near the ridge above the Viser Way Creek. The terrain there dipped sharply, creating a natural funnel. To pass through, enemy armor would need to turn and cross exposed ground. Harlem proposed setting up in a camouflaged position near the treeine, turret reversed, hull slightly angled to protect their weaker rear armor. It wasn’t standard doctrine, but it wasn’t mutiny either. Corbin hesitated. This is a Sherman victory, not a damn rifle on treads. I know, Harlon replied.

But if we try to fight them head-on, they’ll slice us in half. After hours of tense discussion, Corbin relented. One chance you miss were running. They moved into position before dawn. The forest was dead silent. The only sound the distant drip of water and the occasional snap of a frozen branch. They parked C113 in a dip behind a pile of fallen trees. Vickery aligned the 75 mm gun toward the clearing, calculating the angle for when the enemy crested the hill.

And then they waited. Hours passed. The fog thickened, then movement. It began with a low rumble, deep and mechanical. Then the crunch of treads. One tank, then two, then three. Panthers, exactly as he’d predicted. They emerged from the treeine like predators. Sleek, dark, deadly. The lead tank paused to scan the area, its turret rotating slowly. Just a few more feet and it would expose its side plate, the weakest part of the armor. Harlon didn’t breathe. He didn’t speak.

He adjusted his sights with the precision of a surgeon. “Target locked,” he whispered. He fired. The Sherman rocked back with the recoil. The shell sliced through the fog and struck the Panther’s side with a deafening clang, followed by an eruption of flame. The turret blew upward, the tank staggered, and black smoke shot skyward. The other two Panthers slammed their turrets to the left, searching for the source, but Harlon was already moving. He had Rizzo reload, adjusted the sights, and fired again.

The second shot struck the ground near the second tank, sending up dirt and smoke. The third Panther opened fire, but too late. Corbin floored the engine, pulling the Sherman forward out of its hidden nook and behind a treecovered embankment. Two hits, one confirmed kill, and the Panthers were now firing blindly into fog. It was chaos. Corbin radioed in. Enemy armor engaged. One confirmed destroyed. Vicere sniper setup is working. I repeat, working. The reply from headquarters was disbelief, but it didn’t matter.

The tanks were retreating. The shot that rang out through the fog didn’t just destroy a Panther. It shattered the myth that Shermans couldn’t win unless they swarmed. Because one man had just outgunned three enemies using a tactic no manual ever taught. And the forest, soaked in death and silence, was now witnessed to something it had never seen before. A Sherman sniper. From theory to legend. Word of the shot spread faster than the fog could settle. Within hours, other tank crews were talking about it over cold rations and smokes.

“Did you hear about Vicky?” one gunner whispered. “Took out a panther from cover backwards. Most didn’t believe it. Some said it was dumb luck. Others said it was a fluke. But by the next morning, the kill had been confirmed by a reconnaissance patrol. They’d found the burntout wreck, turret blown clean off, a clean entry point right through the side armor. There was no denying it now. Harlon Vickery had done what few in the European theater had accomplished.

He’d taken down a Panther with a 75 mm Sherman from long range with a single shot, and he’d done it without ever being seen. Sergeant Corbin, who had once called it the dumbest idea he’d ever heard, now began calling it Vicar’s Vantage. When headquarters requested an afteraction report, Corbin didn’t sugarcoat it. Private Vicar’s positioning and firing technique are unorthodox, he wrote, but effective. Permission requested to allow further testing of the reverse turret sniper tactic. No reply came.

No official approval, but no one told them to stop either. So Harland did it again. Two days later, at another forest clearing near the town of Commershite, he set up his Sherman along a narrow track just south of the road where tanks were likely to push through in an attempt to flank the American line. He waited, turret turned, engine off. Just before dusk, a column of German armor moved into view. A panzer of fo followed by two halftracks.

Harland fired. The panzer exploded in a fireball that lit the entire treeine. The halftracks scattered. Infantry scrambled into the woods. And for the second time in as many days, Harland’s Sherman escaped without a scratch. By now, his crew was fully bought in. Rizzo started calling the tank the Kentucky rifle. Corbin joked about painting a squirrel mascot on the side. Even support crews started asking about his settings, what elevation he used, how he calculated distance, what type of ammunition worked best.

And behind the scenes, other crews began trying to replicate it unofficially, quietly. Because if there was one thing the Herkin Forest was proving, it was that traditional tactics didn’t work here. You couldn’t brute force your way through minefields and booby trap trails. You had to be smarter. You had to adapt. And that’s exactly what Harlon was doing. But adaptation came at a cost. As his legend grew, so did the danger. The Germans were no fools. They started changing patterns, avoiding the tree lines, sending scouts ahead, firing blindly into suspected ambush points.

One Panther even attempted a counter sniper maneuver, firing high explosive rounds into suspected American tank positions before entering the area. Haron and his crew narrowly avoided death when a shell landed just 20 ft from their position, showering them in dirt and shrapnel. It shook them, but it didn’t stop them because now they weren’t just surviving. They were rewriting the playbook. And somewhere between Commershite and Schmidt, amid frozen boots, jammed radios, and the everpresent stench of Cordite, Harlon Vickery, Farm Kid, Mathbrain, Quiet Thinker was becoming something the war had never seen before.

An armored sniper, a myth with a name, and a turret pointed in the wrong direction. The perfect shot under fire. November 26th, 1944. It was the day the forest exploded. The Germans, desperate to hold the line before the Allies, reached the Rower River, launched a counteroffensive along the K trail and into the villages of Commershite and Schmidt. American infantry were being hammered by artillery and pinned down by dugin machine guns. Panther tanks advanced through narrow booby trapped roads supported by mortars and tree bursting shells that rained down like shrapnel snow.

Harlland’s unit was ordered to hold the southern edge of Commerite. No backup, no air support, just a handful of Shermans, some scattered riflemen, and enough ammunition to last maybe a day, they were told. If you lose this ridge, we lose the whole line. At dawn, the fog returned, thicker than ever. Harland set up his Sherman behind a low stone wall at the edge of the village, facing away from the main road. Again, the turret was reversed. Again, the crew questioned the setup.

“Vickory,” Corbin said quietly. “If they hit us, we’ve got nowhere to run. We’re not going to run, Haron replied. We’re going to hit first. They went quiet. Each man took his position. Rizzo checked the rounds. Two HVAPs loaded first. Then standard armor-piercing, then smoke. The ground shook. German Panthers rolled in. Three of them supported by infantry. Their formation was tight, efficient. They had likely studied American movement and expected frontal resistance, but they weren’t expecting Harlland’s backward turret aimed from the flank.

The first tank crossed into view. Harlon adjusted for distance. 700 yd. The fog shifted just enough to give him a silhouette. He fired. The shell struck low, hit the drive sprocket. The Panther stopped cold, its mobility gone. Flames burst from underneath, but now the second tank opened fire toward the direction of the blast. Debris flew. Trees shattered. The Sherman rocked as a shell detonated behind them. Harlon shouted, “Reload!” Rizzo slammed the next HVAP round into place. Harlon aimed again, this time for the turret ring of the second tank.

He fired. The round punched through. The turret lifted a full 2 ft from the hull before fire consumed the crew compartment. The tank shuttered, then collapsed inward like a dying animal. Then came the third. It saw them. Its gun turned. Slow, deliberate, deadly. Harlon screamed, “Move!” Corbin gunned the engine, but the tracks caught in the mud. The turret of the Third Panther locked on. Then, just as the German tank was about to fire, boom! A shell from another Sherman, an American Sherman, struck it from the opposite side.

Reinforcements had arrived, drawn by the smoke and radio chatter. The third Panther tried to pivot but was caught in a crossfire. It exploded in a column of smoke and steel. The battlefield went quiet. Three Panthers, all destroyed, and Harland Sherman scratched, shaken, scorched, was still standing. They pulled back behind the ridge as medics moved in and infantry pushed forward. Harlon sat in silence, his hands trembling for the first time. You all right? Rizzo asked. Harlon nodded. Yeah, just thinking about what?

That was the shot I was afraid of, he said. The one where you’re already dead before you fire. But he had fired and he’d won. The shot through the fog had been theory. The shot under fire, that was proof. That day, officers began calling Harlland’s tactics long gun doctrine. Some wanted to write it up. Others didn’t know what to make of it. But among the tank crews, those who fought, froze, and bled in the forest, Harlon Vicker’s name started to mean something.

Not just skill, not just survival, but courage to do the opposite of what fear demanded. The imitators, the doubters, and the legacy in motion. In war, legends spread fast, but trust spreads slower. After Commerite, tank crews across the 20th Armored Division started whispering about Vicar’s method. A few tried it, most didn’t. Not because they doubted the kill counts. Those were real, but because they feared the setup. It ran counter to everything they’d been taught. Tank doctrine said, “Face forward.

Charge with strength, fire, maneuver, and stay mobile. What Harlon was doing, reversing into position, sitting still, turret turned backward, felt suicidal. Against German 88 mm guns, one misstep could turn a tank crew into ashes. But the numbers were creeping in. In three confirmed engagements using the backwards setup, Harlland’s crew had destroyed five German tanks, including two Panthers and a Panzer 4, without taking a single hit to the hall. Officers started asking questions not just about Harland, but about doctrine itself.

Could Sherman tanks, long mocked as inferior, actually outperform expectations through smarter positioning? Could a single well-placed gunner, thinking more like a sniper than a tanker, shift the odds in these deadly forests? Harland didn’t care about the debate. He cared about the men inside the tank. He cared about staying alive. And most of all, he cared about not wasting shots. He told a junior crew one night over cold stew, “You don’t fire unless you’re sure. Every shell costs more than metal.

It costs time, noise, and your position. So you wait, you breathe, you think. That’s what made Harlland different. Other gunners shot by instinct. Harland shot by thought, but with fame came friction. One senior officer, Colonel Bennett, dismissed the tactic entirely. Turning your turret backwards is a great way to die looking the wrong way, he said in a briefing. This war is about mobility, not hiding like a coward in the brush. When Harlon heard that, he didn’t get angry.

He just replied, “With all due respect, sir, cowards don’t sit still when panthers roll into view.” The room went silent. Corbin backed him. So did two other tank commanders who’d seen the results firsthand. And slowly, piece by piece, the brass began to allow for situational flexibility in armor engagements. Unofficial language that gave crews the green light to copy what Harlon had created. By December, at least four other crews in the division had begun using modified versions of the backwards sniper setup.

two scored confirmed tank kills. One crew in the 77th Tank Battalion credited the tactic with saving their lives during an ambush west of Gay. They used a downed barn as cover, reversed their turret, waited, and nailed a jagged panzer as it crept past. Unofficially, they named their tank the Vicory Special. But for Haron, it wasn’t about recognition. It never was. He still cleaned his cannon barrel by hand every night. He still wrote in a battered notebook, tracking each shot, its angle, and its result.

And every time they moved to a new position, he scouted the land like a chessboard, looking for fields of fire, blind spots, escape routes. He had become more than a gunner. He was a tactician. And in a war where lives were measured in inches and seconds, that made him dangerous, not just to the enemy, but to old ideas. Because the boy from Kentucky was doing more than killing tanks. He was changing the way American armor thought, the man behind the gun, and the cost of innovation.

By now, Harlon Vickery was known across the battalion, not just as a good shot, but as something else entirely, a quiet force, a thinker in a world of noise. But behind every legend, there’s a cost. December rolled in hard. Snow began to blanket the forest. The cold wasn’t just physical. It was spiritual. Morale dipped. The fighting dragged on. The mud froze into jagged ice. Frostbite claimed fingers, feet, entire limbs. Even the Panthers began to stall from engine failures in the subzero temperatures.

C113 Harlland’s Sherman was now covered in dents soot and the smoke stains of past battles. They never painted it clean again. The scars became part of it, like a warning or a promise. Harlon changed too. He no longer flinched at the sound of incoming artillery. He barely blinked when shrapnel tore through the bark of a nearby tree. But what did shake him, what stayed with him was the silence that came after a shot. the knowing, the moment between the kill and the next breath when he’d realize that another crew, men like him, would never climb out of that burning metal box.

He wrote to his mother, “I don’t know how to feel anymore. Every shot I make saves us, but every shot I make also means someone else’s son doesn’t go home. Sometimes I can still see the hatch opening just before the fire catches. Rizzo stopped joking altogether. Corbin grew more protective, refusing to take unnecessary risks. And Haron began carrying with him a photo of his younger sister, Laya, 8 years old, hair in braids, smiling in front of the same tractor he used to repair back in Kentucky.

He taped it to the inside of the turret just above the rangefinder. “Something to remind me what I’m shooting for,” he said. But even with the emotional weight, he never stopped adapting. In one engagement near the town of Bergstein, he used elevation for the first time, parking the Sherman on a slope, firing downward at a Tiger tank approaching from a road below. The shot pierced the rear engine plate. One shot, one kill. Not out of arrogance, out of necessity, because every round they fired had to count.

By now, the brass had stopped questioning him. In fact, they’d begun quietly assigning him to forward observation roles, not to scout terrain, but to set up kill zones for his sniper tactics. They even brought in a second crew to learn directly from him. But Harlon didn’t see himself as a teacher. He still saw himself as lucky. Still saw himself as the farm kid just trying not to get his friends killed. One night after their 20th mission, Corbin asked him, “What happens when this war is over?” Harlon looked down at his hands, calloused, burned in places from hot shell casings.

“I guess I go home,” he said. “Fix tractors again. Maybe teach my sister how to drive.” And for a moment, it was quiet in the tank. No shells, no radio, just the wind through the trees and the memory of a boy who rewrote the rules. Not to be a hero, but to bring himself and his brothers home. The boy who sniped with a tank. When the snow finally melted over the shattered branches of the Hurkin Forest, it revealed more than shell craters and burntout tanks.

It revealed the ghosts of a doctrine undone, torn not by firepower, but by thought. Among those ghosts was the legacy of one young man, Harlon Vickery. He didn’t change the war with rank or command. He had no battalion under his name, no patented tactic, no battlefield named after him. But what he did have was something far rarer, a mind that refused to accept the way things had always been done. The official reports never used his name. They referenced innovative turret positioning, nonlinear tank deployment, asymmetric armor utilization.

But the crews who came back alive didn’t care for language like that. They just said he showed us we could fight smarter. By early January 1945, Harlland’s tactics had spread beyond rumor. Some commanders quietly instructed crews to scout like snipers, to treat terrain as cover, to fire not first, but best. And yet Harlon wasn’t there to see it. After a third near miss, a shell that killed the crew of the Sherman beside his. He requested to be rotated out.

Not because he was scared, but because he’d seen too many good men die just inches away. He had proven what he came to prove. So they let him go. When he stepped off the train back in Kentucky in the spring of 45, no one saluted. No one cheered. His little sister ran up and hugged him. His father handed him a wrench. His mother set another plate at the table. And that Harlon always said was the best kind of welcome.

He never built a career out of what he did. Never wrote a book, never called himself a sniper. But if you drove by the victory place in the 60s, you might have seen an old war shell on the mantle, polished, empty, harmless. And if you’d asked about it, he’d smile and say, “That’s the one that let me come home.” It’s easy in hindsight to glorify war through numbers. Tanks built, battles won, enemies defeated. But stories like Harlon vicaries remind us that war is not about volume.

It’s about decisions. Micro decisions. Quiet, calculated risks made by men no one notices until it’s too late to forget them. Harlon didn’t win through firepower. He won through a refusal to accept the obvious. He asked a question that nobody else had the courage or foolishness to ask. What if I turn the turret around? And in that question lived the seed of everything that followed. Lives saved, minds changed, and a new way of thinking born not from a textbook, but from the gut of a scared young man in a steel box.

Maybe that’s the real legacy of soldiers like him. Not the number of kills, but the number of lives that didn’t have to die. Because one man decided to look at the battlefield backwards.

News

The Shell That Melted German Tanks Like Butter — They Called It Witchcraft…

The Shell That Melted German Tanks Like Butter — They Called It Witchcraft… The first time it hit, the crew…

Why US Gunners Started Aiming ‘Behind The Target’ — And Shot Down Twice As Many Planes…

Why US Gunners Started Aiming ‘Behind The Target’ — And Shot Down Twice As Many Planes… December 1942, somewhere over…

How One Gunsmith’s “Reckless” Rifling Change Made Bazooka Rockets Penetrate 8 Inches Of Steel…

How One Gunsmith’s “Reckless” Rifling Change Made Bazooka Rockets Penetrate 8 Inches Of Steel… June 1941, a British infantry company…

How One Gunner’s “Suicidal” Tactic Destroyed 12 Bf 109s in 4 Minutes — Changed Air Combat Forever…

How One Gunner’s “Suicidal” Tactic Destroyed 12 Bf 109s in 4 Minutes — Changed Air Combat Forever… March 6th, 1944,…

She Stormed Out of Her Car to Confront the Stranger Who Blocked Her In—Never Imagining the Heated Argument Was With the Powerful CEO Who Signed Her Paychecks

She Stormed Out of Her Car to Confront the Stranger Who Blocked Her In—Never Imagining the Heated Argument Was With…

A Single Father’s Small Act of Kindness Changed Everything—Helping a Lost Girl Reunite With Her Mother Revealed a Truth About Wealth, Love, and Fate He Never Expected

A Single Father’s Small Act of Kindness Changed Everything—Helping a Lost Girl Reunite With Her Mother Revealed a Truth About…

End of content

No more pages to load