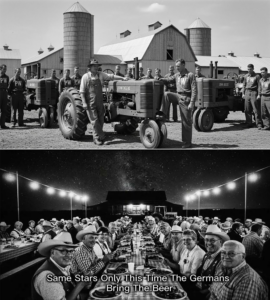

How German POWs on a Remote Midwest Farm Reacted When They Saw Every American Neighbor Owning Three Tractors and Realized the War They’d Been Fighting Was Already Lost

When the train door finally slid open, the first thing Jakob Vogel noticed was the sky.

It was too big.

Not the low, gray ceiling he knew from home, or the smoke-choked haze that had hung over ruined cities in the last months of the war. This sky was wide and clear and startlingly blue, stretching over fields that seemed to go on forever.

“Out,” barked an American soldier, though his tone carried more routine than menace.

Jakob stepped down carefully, boots crunching on gravel. Around him, other German prisoners climbed from the freight cars, blinking in the bright light, uniforms faded, faces hollowed by years of marching and surrender and transport.

Somewhere, a church bell rang. Somewhere else, a dog barked once and then thought better of it.

“Is this the camp?” asked Dieter, the lanky former mechanic who had somehow become Jakob’s shadow since their capture.

“I don’t see any fences,” Jakob replied.

He saw instead a small station building, painted white, with a bench out front and flower boxes under the windows. A woman in a plain dress stood by the door, watching them with wary curiosity but no visible fear.

“Keep moving, fellas,” said another American, younger than Jakob by several years, rifle slung loosely over his shoulder. “Trucks are waiting.”

The prisoners shuffled toward the road.

Jakob had been told, in hurried briefings and rumor-fed whispers, that they were being sent to work. Farms, someone had said. The idea had seemed almost unreal at the time—after years of orders shouted in ruined towns and forests, the thought of fields and harvests felt like a story from his childhood.

Now the story was wrapped in dust and sunlight and the faint smell of hay.

Four open-bed trucks waited by the road, engines chugging. On the side of each, in white paint, were the letters “U.S. ARMY.” A few American guards helped direct the flow of men.

“You, you, you,” one said, pointing. “Truck one. You three, truck two. Let’s go.”

Jakob and Dieter ended up in the same truck, along with ten others. They climbed into the wooden bed and sat on benches that ran along the sides.

The truck jerked forward.

Fields rolled past: corn, already tall; wheat, rippling under the breeze; pastureland dotted with cows that turned their heads with lazy interest.

“So much land,” Dieter murmured. “Empty.”

“Not empty,” Jakob said. “Just… not broken.”

The road stretched between gently rolling hills. As they drove, the prisoners passed farmhouses—some big and white, with broad porches; others smaller, weathered, practical. Beside most of them rose red barns and tall silos.

And something else.

At the first farm they passed, a green machine stood near the barn. Jakob recognized the shape—he had seen photographs once, years ago, in a magazine that had praised modern machines.

A tractor.

He nudged Dieter.

“Look,” he said. “A tractor.”

Dieter nodded. “We had one like that on the estate where I apprenticed. Before the war. The owner guarded it like treasure.”

They passed another farm.

Another tractor.

Then another.

Jakob frowned.

“That is… unusual,” he said, mostly to himself.

Then the truck crested a small rise.

Jakob’s breath caught.

Below them, the land unfolded like a patchwork quilt of fields and farmsteads. At almost every cluster of buildings, he could make out at least one tractor—sometimes two. In one sprawling yard, he counted three distinct machines: one large, one medium-sized, one smaller with narrow front wheels.

“Dieter,” he said slowly, “am I seeing this correctly?”

Dieter leaned forward, squinting.

“Two… three… four…” He began counting under his breath, then stopped, eyes wide. “They can’t all be theirs. Perhaps some are shared…?”

The American guard in the back of the truck, a sandy-haired sergeant with an easy slouch, noticed their stares. He followed their gaze and then grinned.

“First time seeing American farms, huh?” he said in halting German. “Nice view.”

Jakob swallowed.

“All those tractors,” he said. “They belong… to the government?”

The sergeant laughed outright.

“No, friend,” he said. “To the farmers.”

Dieter blinked.

“The farmers?” he repeated. “Each farmer has… one?”

The sergeant shrugged.

“Depends on the farm,” he said. “My old man’s got two. The Russells next door, they got three. Big place. Lot of work.”

He shifted his rifle idly, as if discussing weather.

Jakob stared at him.

He tried, for a moment, to imagine his own village that way. The small patch of land his father had struggled to keep productive. The horse that had pulled their plow for fifteen years. The one rusting machine in the district, shared by three farmers and in constant need of repair.

Three tractors on one farm.

The numbers didn’t fit in his head.

“That’s impossible,” he blurted.

The sergeant raised an eyebrow.

“Looks pretty possible from where I’m standing,” he said. “You’ll see up close soon enough. You’re headed to Mr. Carter’s place. He’s got tractors like my mama’s got dishes.”

The other prisoners exchanged glances.

“Maybe they just leave them there,” muttered one. “Maybe they don’t work. Old scrap.”

But even as he said it, another tractor rolled slowly along a field near the road, pulling a wide piece of equipment that tossed soil behind it in neat, dark waves.

It was very clearly working.

Jakob watched, and for the first time since his capture, a strange new thought crept in beside his exhaustion and resentment.

How can you fight a country that treats its fields like this?

They arrived at the Carter farm an hour later.

The main house was two stories tall, painted white with peeling trim. A big maple tree shaded the yard. Chickens pecked near the porch. A dog lifted its head, decided the truck was uninteresting, and flopped back down.

Behind the house stood a red barn with tall sliding doors opened wide. Beside it, a long shed. A silo rose like a giant metal candle.

And parked near the barn, standing in a row as if ready for inspection, were three tractors.

The first was large and new-looking, its paint still glossy, wide tires thick with dust. The second was older, faded, a few panels patched but clearly in working order. The third was smaller, narrow front wheels set close together, its engine cowling dented but intact.

Jakob counted them twice.

Three.

“Off the truck,” called the sergeant.

They climbed down.

A man stood near the barn, his thumbs hooked in his belt loops. He was in his fifties, with strong shoulders, sunburned forearms, and lines around his eyes that spoke of both years and laughter. His shirt sleeves were rolled up; a wide-brimmed hat cast his face in partial shadow.

Beside him stood a woman around the same age, her hair pulled back with a scarf, her expression guarded but not hostile. A young girl of maybe twelve peeked out from behind her skirt, eyes wide.

“Morning, sergeant,” the man said. “These my new farmhands?”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Carter,” the sergeant replied. “Ten prisoners, all medically cleared for labor. They speak some English, some more than others. Orders say you treat them according to regulations. You know the drill.”

Carter nodded.

“Had Italians last year,” he said. “They worked hard enough once they figured out the milking schedule.”

He turned to the prisoners, taking them in with a steady gaze. His eyes lingered on Jakob for a second longer than the others.

“Name?” he asked.

Jakob hesitated.

“Jakob Vogel,” he said at last.

Carter nodded.

“Well, Jakob Vogel,” he said, “you and your friends are going to help me get this crop in. The army pays me, I feed you and give you cots in the machine shed. You work, you eat. You cause trouble, you go back on the truck. Simple enough?”

Jakob nodded.

“Simple,” he echoed.

The girl by the porch whispered something to her mother, who hushed her gently.

Carter jerked his thumb toward the tractors.

“Ever used one of those?” he asked.

Jakob swallowed.

“I have seen one,” he said carefully. “I have repaired smaller engines. But on our land… we used horses.”

Carter raised an eyebrow.

“Horses,” he repeated. “You plowed with horses.”

“Yes.”

The older tractor caught Dieter’s eye. He stepped forward, forgetting for a moment that he was a prisoner.

“That one…” he said, “it is an Allis-Chalmers, yes? Model from before the war.”

Carter’s face flickered with surprise and something like respect.

“You know your machines,” he said.

“I was a mechanic,” Dieter replied. “Before.”

“Well then,” Carter said, “you’ll like it here. We’ve got more engines than hands some weeks.”

He clapped his hands once, decisively.

“All right,” he said. “You’ll get settled, then we’ll talk chores. Supper’s at six. My wife doesn’t cook separate meals, so if you’re hungry, you’ll get what we get.”

Hungry was an understatement.

They were starved.

The smell from the house already suggested things Jakob hadn’t seen on a plate in years: bread, thick and warm; meat; something with sugar in it.

As they followed a young American private toward the machine shed, Jakob glanced back at the tractors.

Three.

Each big enough to pull the plow that had once taken two of their best horses all day to drag.

His mind worked the numbers again.

Hours.

Days.

Seasons.

“Dieter,” he said under his breath, “do you know what this means?”

Dieter looked at him, eyes bright.

“Yes,” he said. “It means we were wrong about something much bigger than the front lines.”

Their first day on the farm was a blur of new routines wrapped around old exhaustion.

They were given cots in the machine shed—simple canvas stretches lined up along the wall, with straw-filled mattresses and rough blankets. To men who had slept in foxholes and on barracks floors, it felt almost luxurious.

At noon, they were fed.

Jakob sat at a long wooden table under a tree, a metal plate in front of him, steam rising from thick slices of potato, roasted chicken, and green beans that tasted like they had been picked that morning.

He took his first bite in disbelief.

The chicken was tender, the potatoes buttery, the beans crisp.

He had expected thin soup and crusts of bread. Rationed sugar, maybe. Something as tired as the men who served it.

Instead, every bite tasted like someone had not yet learned to be afraid of tomorrow.

“You eat like this… every day?” he asked the private assigned to watch them, a young man named Tom who spoke German with evident school-day pride.

Tom shrugged.

“More or less,” he said. “My ma cooks better, though. Mrs. Carter is in a hurry—too many mouths to feed.”

Jakob nearly choked.

Too many mouths to feed.

In his village, one chicken like this would have fed a family of four for two days. Here, it was a midday meal for a dozen people and three prisoners who had, until recently, been the enemy.

“And this is during war?” Dieter asked softly.

Tom frowned.

“Yeah,” he said. “Guess so.”

He sounded almost puzzled, as if he had never considered that his country was at war and yet still full of food.

Jakob stared at his plate.

A thought flickered at the edges of his mind, one he pushed away quickly:

What do their tables look like in peace?

In the following weeks, the German prisoners became part of the rhythm of the Carter farm.

They were given chores according to strength and skill. Jakob, with his steady hands and knack for understanding how things fit together, found himself working with Carter in fields and on machinery.

The first time he touched the steering wheel of a tractor, his palms tingled.

“All right,” Carter said, climbing up onto the step beside him. “This one’s the older Allis. Good for plowing, planting, pulling half the county if the tires don’t burst. You respect it, it’ll respect you.”

He pointed at the controls.

“Throttle, clutch, brake. You want to move, you ease off the clutch, feed it a little gas. You want to stop, you think about it before the ditch shows up.”

Jakob smiled despite himself.

“Yes,” he said. “I have driven trucks. This is… larger, but familiar.”

Carter watched him closely.

“You treat it like a truck, you’ll break something,” he said. “This machine lives in the field. You gotta feel the soil through the seat. You listen to the engine. It’ll tell you when it’s angry.”

He had the easy, affectionate way with the machine that farmers had with their animals.

Jakob settled his feet.

He pressed the clutch, turned the key, and felt the engine shudder to life.

The power was immediate, tangible. It thrummed under him like a living thing.

“Takes some getting used to,” Carter said, raising his voice over the noise.

“Yes,” Jakob replied.

But deep inside, something else was getting used to a different idea:

One of these equals how many men with shovels? How many horses? How many days?

They drove slowly at first, then faster, turning in wide arcs at the edge of the field.

By late afternoon, Jakob could guide the tractor in relatively straight lines—straight enough to please Carter, who nodded gruffly.

“Not bad,” he said. “Tomorrow we’ll put some equipment on the back and see how you handle real work.”

As they parked the machine near the barn, Jakob saw the other two tractors sitting side by side.

“Why three?” he asked, unable to hold the question back any longer. “Why not one? Or two? Quite enough, I think.”

Carter wiped his hands on a rag.

“Because if one breaks, I still got two,” he said. “Because some tools do one job better than another. Big John Deere there”—he gestured at the largest—“pulls the heavy stuff. That little Ford? Nimble. Good for cultivating without crushing the crops. This Allis is my old reliable. Friend in a pinch.”

He considered Jakob for a moment.

“You don’t have that where you come from?” he asked.

Jakob thought of his father’s fields, the worn harness, the single plow, the one machine that had been shared between neighbors like a precious heirloom.

“No,” he said. “We had one plow. Shared. And a machine in the village the party men said was proof that we were ‘modern.’”

He heard the bitterness in his own voice and let it hang there.

Carter watched him.

“Well,” he said at last, “maybe when this is all over, you’ll take some ideas home.”

He clapped Jakob lightly on the shoulder.

“Come on,” he added. “Chickens won’t feed themselves.”

The more Jakob saw of American farming, the less he understood his own war.

It wasn’t just the tractors.

It was the way the fields were laid out, the fertilizers applied, the combine harvesters that appeared at the edge of late-summer wheat like hungry metal beasts, swallowing rows of grain in minutes.

It was the way Carter talked about ordering new parts from a catalog, as if steel and rubber and bolts could be conjured from paper and postage.

It was the way neighbors arrived in trucks to help with big tasks, not dragged by orders but arriving with pies and jokes and extra hands.

One evening, after a long day baling hay, the prisoners sat on the back step of the machine shed, watching the sunset smear orange and pink across the sky.

Dieter spoke first.

“I have been counting,” he said quietly.

“Counting what?” Jakob asked.

“For each of Carter’s tractors, how much work could be done with men instead,” Dieter replied. “One tractor pulling a plow does the work of maybe… what… twenty men with shovels, over a day? Perhaps more. So three tractors…”

He trailed off, doing math in his head.

“And this is one farm,” he said. “One family. Multiply by all the farms we saw from the truck. Multiply by the rest of this state. Multiply by all the states.”

Jakob stared at the dark shapes of the tractors near the barn.

“You’re saying the Americans have an army,” he said slowly, “made of machines. That never wears out, never goes hungry, never sleeps.”

Dieter nodded.

“And we were told,” he added, his voice tightening, “that we could outlast them. That our will would overcome their factories.”

He kicked at a small stone.

“I think,” he said, “that those speeches never visited these fields.”

Lea, who had been mending a torn shirt with neat, precise stitches, looked up.

“We are alive,” she said. “We sit here. We breathe. That is something. Better than lying under the fields we left behind.”

Jakob nodded.

“But if I had known this,” he said, “when I was twenty and full of slogans… would I have been so eager to march?”

No one answered.

The question hung in the evening air, as persistent as the hum of distant crickets.

Summer turned to early autumn.

The work shifted from planting and tending to harvesting. Jakob drove tractors while Carter rode on attached equipment, adjusting controls as grain poured into wagons.

The rhythm of the engine became a kind of music to him. He began to sense when a belt was too loose, when a bearing was too hot. He and Dieter spent evenings in the shed, cleaning air filters, checking oil, discussing designs.

“Look how thick this steel is,” Dieter would say, running his hand along a bracket. “Someone designed this to last twenty years.”

“And the spare part arrives in a box with instructions,” Jakob would reply. “Printed instructions. Not whispers and improvisation.”

One afternoon, as they paused to refuel, Jakob noticed Carter watching him with a curious expression.

“You ever think about staying?” Carter asked, almost casually.

Jakob froze.

“Staying?” he repeated.

“In this country,” Carter said. “After the war. Not here on my farm necessarily—though I wouldn’t say no to a good mechanic—but in general. There’s land out west. Towns growing. Factories. They’ll need men who know machines.”

A year earlier, Jakob would have laughed in his face.

Now, he found he could not summon the laugh.

“I have family,” he said at last. “Or… I had. I don’t know now. The last letter from my sister came before… everything.”

He gestured vaguely toward the east, where an entire continent lay between him and the past.

Carter nodded, his gaze softening.

“I get that,” he said. “I’d want to know too.”

He wiped sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand.

“Still,” he added, “if you ever do decide, there’s room. This country’s big. Bigger than you’ve seen.”

He patted the side of the tractor.

“And we’ve got work,” he said. “So much work.”

Jakob looked at the machine.

He thought of the speeches he’d heard in his youth—about destiny and struggle and superiority. He thought of the reality he had seen—of shortages, ration cards, scavenged parts.

He thought of three tractors on one farm.

“You fight a war,” he said slowly, more to himself than to Carter, “believing that your hardship proves your strength. But what if it only proves your leaders never learned how to keep their people fed?”

Carter frowned, not fully understanding.

“What’s that?” he asked.

Jakob shook his head.

“Nothing,” he said. “Thinking out loud.”

News arrived in pieces.

A radio in the farmhouse kitchen crackled with bulletins that the prisoners were not always allowed to hear. Still, the big stories slipped through: a beach with a strange name; a surrender in one theater; rumors of terrible new weapons in another.

One crisp morning, Mrs. Carter came out to the machine shed with a folded newspaper in her hand.

Her face looked different.

“Mr. Carter,” she called, voice tight. “You better come see this.”

He took the paper from her, scanned the front page, then let out a long, low whistle.

Tom, the young guard, peered over his shoulder.

“It’s over?” he asked. “Really over?”

“Looks like it,” Carter said. “Germany’s surrendered. Official.”

He looked up at the German prisoners.

“Well,” he said softly, “that answers that.”

Silence fell over the shed.

Jakob felt it like a physical weight.

The war—this huge, all-consuming thing that had taken seven years of his life and countless more from others—had ended not with a bullet or a blast he could see, but with black ink on white paper in a faraway city.

Dieter sat down on an overturned crate, as if his legs had given out.

Lea’s mouth trembled once, then settled into a tight line.

Jakob stepped forward slowly.

“May I see?” he asked.

Carter hesitated for a fraction of a second, then handed him the paper.

The headline was large, in bold letters he could sound out even in English:

“GERMANY SURRENDERS. WAR IN EUROPE ENDS.”

The words swam on the page.

Underneath, there was some mention of unconditional terms, of Allied leaders, of dates and times.

Jakob read none of it.

His eyes drifted instead to a photograph printed on the front—the face of a general, the image of a document being signed, flags.

He thought of his father’s small house.

He thought of the fields he had left behind.

He thought of the tractors parked outside.

“We lost,” he said quietly.

No one contradicted him.

It was too obvious now.

Not just in the newspaper.

In everything.

In the plates of food that appeared every day as if summoned by routine rather than desperation.

In the spare parts that arrived in crates instead of being scavenged from wrecks.

In the three tractors on one farm.

Carter rubbed the back of his neck.

“War’s over,” he said. “That’s not the same as ‘you lost’ and ‘we won,’ not the way folks like to shout it. Lot of people on all sides lost more than they can say.”

He shrugged.

“But, yes,” he added. “Your government signed papers saying they gave up. That’s the official answer.”

Jakob handed the newspaper back.

He felt strangely hollow.

He had expected to feel rage.

He felt something closer to… release.

And underneath it, a question that wouldn’t let him go:

If we had seen this place before the war, would any of us have believed we could beat it?

Months passed.

The formal end of the war did not mean immediate freedom for the prisoners. There were procedures, transports, decisions to be made about repatriation. For the moment, they stayed on the farm, working through the harvest, then the preparations for winter.

The tractors kept rolling.

Jakob grew familiar with every rattle and hum.

One evening, as they lubricated joints and wiped down surfaces before closing the barn doors, Dieter spoke up.

“Do you remember the first day we were here?” he asked.

“Yes,” Jakob said. “You tried to explain to the guard that his fuel lines were routed inefficiently.”

Dieter snorted.

“Not that,” he said. “The moment on the road. When we first saw the tractors.”

Jakob smiled faintly.

“Yes,” he said. “I remember.”

“I thought it was a trick,” Dieter admitted. “Some kind of show. Bring the prisoners past the richest farms, make them feel small. But this…” He waved his rag at the horizon, where lights from distant farmhouses glowed. “This is just… how it is.”

“Yes,” Jakob agreed.

“And you remember what you said?” Dieter pressed.

Jakob frowned.

“I said many foolish things,” he replied.

“You said,” Dieter continued, “that you didn’t understand how we could fight this and expect to win.”

Jakob nodded slowly.

“I was being polite,” he said. “What I meant was: the war was lost before it began. We just didn’t know it yet.”

He looked at his hands.

“I thought we were the strong ones,” he said quietly. “Our leaders told us that hardship was proof of our superiority. That suffering made us pure. That luxury made others soft.”

He exhaled.

“But here, in the middle of nowhere, a farmer has three tractors and a pantry full of food and still sends his son to the army,” he said. “Tell me, Dieter—who was really strong?”

Dieter said nothing.

He didn’t need to.

The tractors stood behind them, silent now but full of potential energy.

Jakob put his hand flat on the hood of the old Allis.

The metal was still warm from the day’s work.

He closed his eyes.

In that moment, he realized that his understanding of power had shifted forever.

Not from guns to machines.

From slogans to storage barns.

From flags to harvests.

Years later, long after he had been repatriated, Jakob found himself standing at the edge of a small field in a changed Germany.

The war scars were still there—some visible, some buried—but new buildings had risen. New factories hummed. New roads stretched across the landscape.

And in his field, painted a bright, defiant green, stood a tractor.

Not as big as Carter’s top-of-the-line model had been.

Not as new.

But it was his.

He had bought it with money saved from odd jobs and careful planning. He had assembled it with his own hands, with a manual translated into his own language. He had felt the engine turn over for the first time like a promise.

Now, his son, a boy of ten with serious eyes, stood beside him.

“Papa,” the boy asked, “is it true that when you were a prisoner, every American farmer had three of these?”

Jakob smiled, the lines around his eyes deepening.

“Not every farmer,” he said. “But enough that it shocked me.”

The boy frowned.

“Why?” he asked. “We have one.”

Jakob rested a hand on his son’s shoulder.

“Because,” he said, “I had been told all my life that we were the most advanced, the most prepared, the strongest. I believed it. And then I saw a place where machines worked while people slept, where food grew faster than armies could march, where ordinary farmers owned more engines than our whole village.”

He nodded toward the tractor.

“This,” he said, “is not just a machine. It is a memory. It reminds me that loud speeches cannot fill an empty pantry. It reminds me that a country that feeds its people has already won half its battles before they begin.”

His son thought about that.

“Did you hate them?” he asked. “The Americans?”

Jakob looked at the boy against the backdrop of the field, the house behind them, the sky above—smaller than the one he had first seen stepping off the train, but still open.

“I thought I did,” he said. “Then I worked their land. I broke their bread. I learned to fix their tractors. I realized that some of the things we envied most were things we could build ourselves if we stopped listening to voices that only knew how to shout.”

He knelt beside his son, so their eyes were level.

“People will tell you, all your life,” he said, “that strength comes from flags and speeches and marching. Remember what I’m telling you now: strength also comes from full barns, from good tools, from neighbors you can borrow a wrench from.”

He smiled, remembering Carter’s rough clap on his shoulder, Mrs. Carter’s dinners, Tom practicing German with clumsy enthusiasm, the hum of the generators, the scent of fresh-cut hay.

“And from knowing,” he added, “when to stop fighting and start rebuilding.”

His son nodded solemnly.

“Can I drive it?” the boy asked, glancing at the tractor.

“Someday,” Jakob said. “When your legs reach the pedals and you promise to listen when the engine talks.”

The boy grinned.

They walked back toward the house together.

As they reached the door, Jakob looked back one more time.

In his mind’s eye, he saw again that first long view of the American countryside—the rows of farmhouses, each with their barns and silos and, astonishingly, their multiple tractors.

He remembered the hollow shock in his chest.

He remembered the tears he had hidden at the edge of the machine shed when he had realized what that meant.

The world would keep telling the story in simplified form:

“German POWs couldn’t believe American farmers had three tractors each.”

People would repeat it as a curious anecdote from a distant war.

They would laugh.

They would shake their heads.

They would say, “Can you imagine?”

But for Jakob, it would never be a joke.

It had been the moment he understood that his world was smaller than he’d been told—that his country had sent its sons to fight not just armies, but an entire way of life that could grow food and machines faster than fear.

And the real shock, the one he carried with him long after the fences and guard towers were gone, was this:

He had thought he was seeing the enemy’s strength.

In truth, he was seeing a future his own country could choose to build—if it ever learned that power was not only measured in guns, but in how many tractors stood quietly in the yard at sunset.

He opened the door and stepped inside.

Behind him, the tractor waited for morning.

THE END

News

BEHIND THE LIGHTS & CAMERAS: Why Talk of a Maddow–Scarborough–Brzezinski Rift Is Sweeping MSNBC — And What’s Really Fueling the Tension Viewers Think They See

BEHIND THE LIGHTS & CAMERAS: Why Talk of a Maddow–Scarborough–Brzezinski Rift Is Sweeping MSNBC — And What’s Really Fueling the…

TEARS, LAUGHTER & ONE BIG PROMISE: How Lawrence O’Donnell Became Emotional During MSNBC’s Playful “Welcome Baby” Tradition With Rachel Maddow — And Why His Whisper Left the Room Silent

TEARS, LAUGHTER & ONE BIG PROMISE: How Lawrence O’Donnell Became Emotional During MSNBC’s Playful “Welcome Baby” Tradition With Rachel Maddow…

🔥 A Seasoned Voice With a New Mission: Why Rachel Maddow’s “Burn Order” Is the Boldest Move MS Now Has Made in Years — and the Hidden Forces That Pushed It to the Front of the Line 🔥

🔥 A Seasoned Voice With a New Mission: Why Rachel Maddow’s “Burn Order” Is the Boldest Move MS Now Has…

They Mocked the Plus-Size Bridesmaid Who Dared to Dance at Her Best Friend’s Wedding—Until a Single Dad Crossed the Room and Changed the Whole Night’s Story

They Mocked the Plus-Size Bridesmaid Who Dared to Dance at Her Best Friend’s Wedding—Until a Single Dad Crossed the Room…

The Night a Single Dad CEO Stopped for a Freezing Homeless Girl Because His Little Daughter Begged Him, and the Unexpected Reunion Years Later That Changed His Life Forever

The Night a Single Dad CEO Stopped for a Freezing Homeless Girl Because His Little Daughter Begged Him, and the…

The Young White CEO Who Refused to Shake an Elderly Black Investor’s Hand at Her Launch Party—Only to Be Knocking on His Door Begging the Very Next Morning

The Young White CEO Who Refused to Shake an Elderly Black Investor’s Hand at Her Launch Party—Only to Be Knocking…

End of content

No more pages to load