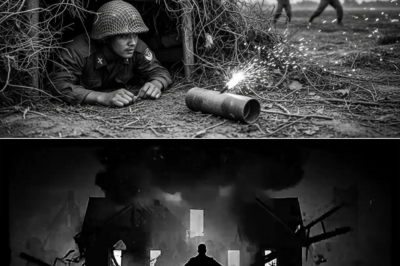

How an Ordinary Snowplow Became General Patton’s Unexpected Lifeline, Opening a Frozen Road to Bastogne and Transforming a Desperate Winter Standoff Into One of the Most Unlikely Turnarounds in Modern Battlefield History

The December wind cut across the Ardennes like a blade, sharp enough to sting through the thickest wool coat. Snow had been falling for days, blanketing every farmhouse, road, and treetop in a white silence that swallowed sound and hope alike. To most people trapped in that merciless winter, the storm felt like nature’s way of saying stop. But for the men encircled in the small town of Bastogne—cold, exhausted, and nearly out of supplies—stopping wasn’t an option.

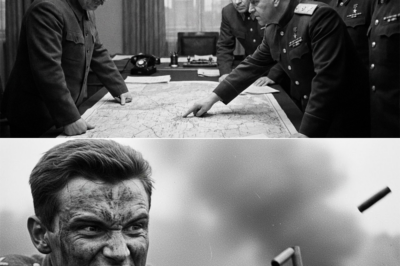

Far to the south, General George S. Patton paced inside his temporary headquarters like a restless storm. The Battle of the Bulge had erupted with frightening speed, and Bastogne—strategically perched at the crossroads of several vital routes—was now surrounded. Patton’s Third Army had been ordered to break through and relieve the troops trapped inside.

But the roads…

The roads were frozen walls of snow and ice, jammed with drifts waist-high. The tanks couldn’t pass. Trucks couldn’t move. Even jeeps spun helplessly like toys on polished glass. The most powerful armored force in Europe was pinned down by the simplest force on earth—weather.

Patton hated excuses. He hated obstacles. But more than anything, he hated delay.

He studied the maps, planned and replanned, sought alternate routes, and pushed his officers for solutions, yet every conversation circled back to the same problem:

No road, no rescue.

That night, a convoy of support vehicles rolled into camp, and among them was something Patton barely noticed at first—a battered snowplow attached to a humble maintenance truck. It looked almost comical, dwarfed by tanks and self-propelled guns around it. The paint was chipped, the steel blade dented. It had been requisitioned from a civilian depot miles away.

Patton stopped in his tracks. His eyes narrowed, then widened with a spark of curiosity.

“Whose truck is that?” he demanded.

A young lieutenant stepped forward nervously. “Sir, just a plow we picked up for clearing supply routes.”

Patton approached the machine as though it were a rare artifact. He ran a gloved hand across the blade.

“A plow…” he muttered. “Move snow… open roads…”

Then, turning sharply: “Lieutenant, can this push a drift taller than a man?”

The lieutenant swallowed. “With enough passes, sir—yes.”

Patton didn’t blink. “Then it’s not a snowplow. It’s the spearhead of the Third Army.”

The order spread like lightning. Mechanics were pulled from their cots. Drivers were summoned from mess tents. A quiet maintenance vehicle suddenly became the center of the entire operation. Chains were fitted to the tires, lights reinforced, fuel cans stockpiled. Tank crews watched with raised eyebrows, some smiling, some doubting, but Patton didn’t care.

The storm worsened through the night, yet by dawn, engines roared and the march toward Bastogne began.

The plow—driven by Sergeant Thomas Kearney, a man more used to farm roads than battlefields—rolled ahead of the entire column. Behind him stretched tanks, armored carriers, trucks filled with supplies, and thousands of soldiers desperate to reach their trapped comrades. Every man depended on that plain, rumbling vehicle to carve a path through the frozen wilderness.

The first hour seemed almost easy. The plow shaved through shallow drifts, tossing snow aside like white spray from a ship’s bow. But deeper into the forest, the drifts thickened. Snowbanks rose like walls. Ice turned the road into glass. Kearney gripped the wheel until his knuckles went pale. The plow slammed into drifts with a crunch that shuddered through the frame. The engine growled. Snow exploded outward. And slowly, foot by foot, the road opened.

Patton followed behind in his command vehicle, watching intently.

“Look at that,” he said to his aide. “One man, one machine, doing the job nature swore we couldn’t.”

But nature wasn’t finished yet.

Around midday, the wind picked up, hurling flakes sideways in blinding sheets. Drifts collapsed back onto the freshly cleared path. Trees groaned under the weight of ice. Visibility dropped to almost nothing. Several trucks slid off the road and had to be pulled back by tanks. The plow’s windshield iced over faster than Kearney could scrape it. He cracked a window to peer out, letting freezing air slash across his face.

Behind him, traffic slowed. Engines sputtered. Men coughed into scarves stiff with frost. Some wondered whether the mission was doomed.

Then Patton stepped out into the storm.

He stood in the road, coat snapping in the wind, and pointed ahead.

“Keep that plow moving!” he shouted. “If the road closes, the rescue dies. And we don’t let anything die today.”

His voice carried through the storm like a challenge to the sky itself.

Kearney pushed forward.

The plow carved another mile. Then another. And another. Each stretch opened a new artery for the massive steel column behind it. Tanks rumbled, trucks lurched, wheels spun, but they kept moving.

Hours later, the plow approached a frozen rise where wind had built a drift nearly eight feet tall. It looked like a white cliff, smooth and hard as stone. Kearney slowed. The engine coughed.

For a moment, doubt crept in.

Patton stepped to the plow’s door, his face frosted, his eyes burning with determination.

“Sergeant,” he said, “you break this drift, you break the siege.”

Kearney nodded once, tightened his grip, and gunned the engine.

The plow slammed into the drift with a thunderous crack. Snow burst upward in a blinding spray. The truck shuddered violently but kept pushing. Tires spun. The blade gouged. Inch by inch, the machine crawled forward. Men along the roadside held their breath.

Finally, with a roar that sounded almost triumphant, the plow punched through the other side.

A cheer went up along the column—an eruption of hope in a place where hope had frozen days ago.

From there, the advance accelerated. By evening, the first elements of Patton’s Third Army reached the outskirts of Bastogne. The troops inside, weary but unbroken, erupted in relief as the long-awaited column rolled through the snow-choked approaches, bringing food, blankets, medicine, and the promise that they were no longer alone.

The plow, caked in ice and battered beyond recognition, rolled into the town like an unlikely hero. Soldiers gathered around it, patting the hood, laughing, shaking Kearney’s hand. The humble machine had become a symbol—proof that sometimes victory doesn’t come from the loudest weapon or the largest force, but from the simplest tool used at the right moment by people refusing to give up.

That night, Patton walked up to the plow and rested a hand on the dented blade.

“In this war,” he said softly, “courage shows up in many forms. Today, it showed up wearing a snowplow.”

The storm continued to fall around him, but Bastogne was no longer trapped. The road—once buried and impassable—now stood open, carved by determination, steel, and a little machine that refused to quit.

And in the long years that followed, when historians wrote about the Battle of the Bulge, many focused on strategy, on maps, on famous speeches and daring maneuvers. But among the men who marched through that frozen forest, there was a quieter legend—of the day a snowplow became the sharpest blade in Patton’s arsenal.

THE END

News

When an Arab Billionaire Tested Everyone in His Native Language, Only the Quiet Waitress Responded — And What Happened Next Left the Entire Restaurant Frozen in Awe and Completely Transformed Her Life Forever

When an Arab Billionaire Tested Everyone in His Native Language, Only the Quiet Waitress Responded — And What Happened Next…

The Night a Hardened Billionaire CEO Dropped His Drink in Shock When a Quiet Waitress Revealed a Family Birthmark—Unraveling a Hidden Past, a Lost Connection, and a Life-Changing Truth Neither of Them Knew They Were Searching For

The Night a Hardened Billionaire CEO Dropped His Drink in Shock When a Quiet Waitress Revealed a Family Birthmark—Unraveling a…

Wealthy Businesswoman Secretly Leaves Her Newborn With a Quiet Gas-Station Janitor — Only To Return Five Years Later and Freeze When She Discovers What He’s Done With the Child’s Life

Wealthy Businesswoman Secretly Leaves Her Newborn With a Quiet Gas-Station Janitor — Only To Return Five Years Later and Freeze…

How a Young Black Woman Faced Birthday Heartbreak on a Failed Blind Date, Only to Have a Brave Little Girl Approach Her With a Question So Pure and Unexpected That It Changed Both of Their Lives Forever

How a Young Black Woman Faced Birthday Heartbreak on a Failed Blind Date, Only to Have a Brave Little Girl…

How One American Soldier’s Improvised “Mine-Throwing” Technique Was First Rejected by Nervous Commanders, Then Proven So Effective in a Single Daring Moment That It Turned Three Enemy Strongholds Into Openings for an Unstoppable Advance

How One American Soldier’s Improvised “Mine-Throwing” Technique Was First Rejected by Nervous Commanders, Then Proven So Effective in a Single…

The Secret Conversation Inside the Kremlin When Stalin First Understood That German Forces Might Reach Moscow Before Winter — And the Remarkable Shift in Mindset That Sparked a Fierce, Strategic Struggle for the Capital’s Survival

The Secret Conversation Inside the Kremlin When Stalin First Understood That German Forces Might Reach Moscow Before Winter — And…

End of content

No more pages to load