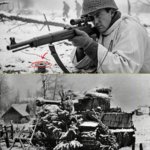

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare Rifles, Ignored His Own Commissar’s Orders, and Turned One Hill Into a “Forest of Ghosts” That Killed 225 Attackers and Broke the Siege

The first thing Sergeant Nikolai Sokolov ever shot wasn’t a person.

It was a crow.

He was twelve years old, standing in the thin birch forest outside his village in the Ural foothills, holding his grandfather’s single-shot hunting rifle with sweaty hands. The crow sat on a branch, black against the pale sky, watching him with one bright, indifferent eye.

“You breathe first,” his grandfather had said. “Then you shoot. Not the other way around.”

The sound of that shot had echoed through the trees for a long time.

By the time Nikolai was twenty-three, the echoes were different.

Artillery. Machine guns. Shouts in languages he didn’t understand and ones he did, all mashed together into one long, terrible noise that never really stopped.

The crow had fallen without understanding what had hit it.

The men he was shooting at now… they understood exactly.

Winter 1942, somewhere west of Stalingrad.

The ground was frozen hard enough that every step crunched.

Snow lay in dirty ridges, piled against tree trunks and shallow trenches. Breath hung in front of faces like ghosts that hadn’t decided where to go yet.

Nikolai lay on a low rise, the barrel of his Mosin-Nagant sniper rifle resting on a folded blanket, eye pressed to the PU scope.

Through the fogged lens, the world narrowed.

German helmet.

Shoulder.

Half a face above a shovel.

They were digging in along the tree line opposite his brigade’s positions, using their last hour of dull gray daylight to carve shelter out of the frozen earth.

He put the crosshairs just above the visible cheekbone—enough for gravity and distance—and exhaled sluggishly through his nose.

His finger tightened.

The rifle cracked.

The man dropped behind the lip of his half-dug foxhole, spade flying from his hand.

Nikolai blinked once, lifted his head a fraction, and scanned.

To his left, another German jerked, startled, ducked. A third turned, shouting something.

Nikolai shifted, sighted on a figure who’d popped up behind a short stump to look for the source of the shot.

Another breath.

Another squeeze.

Another crack.

Another body in the snow.

He didn’t count them as they fell.

He counted them afterward, because his commanders wanted numbers.

Numbers went into reports.

Reports went into the mouths of political officers and into newspapers, where they became stories about heroes and villains and unbreakable will.

Reality was simpler.

You stayed alive as long as you could.

You tried to keep the people next to you alive, too.

If the reports turned that into something glorious, that was their business.

That night, in a commandeered farmhouse with frost on the inside of the windows, the battalion staff crowded around a rough table.

Kerosene lamps cast yellow light on hollow faces.

Captain Leonid Volkov, the battalion commander, traced the lines on a mud-stained map with his finger.

“Here,” he said, tapping a small, unpleasantly narrow bulge. “That’s us.”

The bulge was a small Soviet foothold jutting into German lines. On either side, thick blue pencil marks indicated enemy positions. The battalion had been ordered to hold the hill that anchored the bulge.

If they lost it, the line would straighten.

Along with a lot of graves.

“And here,” Volkov continued, tapping the map behind their position, “is where the rest of the regiment was supposed to be. Supporting us. But the Germans hit them with tanks and artillery this afternoon. Command says they’ve had to fall back to secondary positions.”

“So we’re out in front,” said Senior Lieutenant Pasha Vinogradov, the artillery liaison, his voice flat. “Alone.”

“For now,” Volkov said. “Division promises counterattacks tomorrow. We just have to hold until then.”

He didn’t need to say the rest.

If they actually come. If the Germans don’t break us first.

In the corner, sitting straighter than anyone else, Political Officer (Zampolit) Viktor Petrov listened with the narrowed eyes of a man who measured everything against a manual in his head.

“Hold,” Petrov said. “That is the order from above. And we will obey it.”

His uniform was cleaner than most. His boots had fewer scuffs. His hands, when he placed them on the table, were not chapped and cracked like some of the others.

Nikolai stood near the stove, thawing his gloved fingers.

He looked tired in a way that had nothing to do with sleep.

Volkov turned to him.

“Your report, Sokolov?” he asked.

Nikolai straightened.

“Seventeen confirmed kills today, comrade captain,” he said. “Mostly machine-gun crews and forward observers. A few officers. No enemy armor spotted near our sector, but movement suggests they are shifting troops to our flank.”

Petrov raised an eyebrow.

“Only seventeen?” he asked. “When Comrade Zaitsev writes in the papers that some snipers kill dozens in a week, this seems… modest.”

Nikolai met his gaze without flinching.

Zaitsev. The famous sniper from Stalingrad. Hero of the Soviet Union. Name on posters.

Nikolai had read the articles.

He’d also seen men die trying to live up to them.

“I can only confirm what I see,” Nikolai said. “If they fall behind cover where we can’t count them, I don’t write them down.”

Petrov sniffed.

“Accuracy is important,” he said. “For the record. And for morale.”

“Morale,” Volkov said dryly, “will be greatly improved if we are not overrun in the morning.”

He tapped the map again.

“The Germans pushed us hard today,” he said. “We stopped them at the tree line. Barely. They’ll attack again at first light. Intel says they’ve got at least one full infantry battalion opposite us now. Maybe more.”

“How many rifles do we have?” Nikolai asked.

“After the casualties today?” Volkov said. “Two hundred and ten men in the line company with working weapons. Plus support, plus the wounded who can still hold a rifle if we have to drag them back to the trench.”

“So we’re outnumbered,” Nikolai said.

“Yes,” Volkov said.

Petrov stiffened.

“We have the advantage of defending,” he said. “We have the advantage of fighting for our land, our people, our—”

“We have less ammunition than they do,” Nikolai said, voice quiet but steady. “Last resupply was three days ago. We fired most of what we had today.”

The room went still.

Volkov’s jaw tightened.

“Rifle ammo is down to about thirty rounds per man,” Vinogradov said reluctantly. “Machine guns are better, but not by much. Mortars have a handful of bombs. Our attached artillery battery has fired through most of their allotment. They might manage a short barrage tomorrow, but not much.”

“And the Germans?” Nikolai asked.

“Truckloads,” Vinogradov said. “Always.”

He wasn’t being dramatic.

They’d all heard the difference.

When the Germans attacked, their machine guns didn’t stutter because someone was counting rounds. Their mortars kept thumping. Their rifles cracked and cracked and cracked.

The Red Army had numbers.

The Wehrmacht had logistics.

Sometimes those numbers and that logistics met in the worst possible places.

“Command says if we can hold this hill until midday,” Volkov said, “the regiment will counterattack from the south and relieve pressure. If we can’t…”

He didn’t finish.

He didn’t have to.

Petrov leaned forward.

“We will hold,” he said. “We have the Party behind us. We have the Motherland. We have—”

“We have thirty rounds per rifle,” Nikolai repeated. “And an enemy with more men, more bullets, and likely more mortars than we do.”

Petrov’s eyes flashed.

“Are you suggesting,” he said, “that we disobey orders?”

Nikolai shook his head.

“I am suggesting we think of ways to make those thirty rounds count for more,” he said. “Ways to make them believe we have more rifles than we do.”

Volkov’s gaze sharpened.

“What are you thinking, Sokolov?” he asked.

Nikolai hesitated.

He looked at the map.

Then at the stove.

At the men gathered around the table.

At the pile of damaged and spare weapons stacked near the door—rifles with broken stocks, jammed bolts, ones taken from the fallen and set aside for later repair.

“How many spare rifles do we have?” he asked.

Duffy—no, that was the other front, he corrected himself mentally; here, it was Sergeant Mikhail Antipov, the armorer—grunted.

“Forty?” Antipov said. “Maybe fifty. Most are damaged. Some are German. Why?”

Nikolai’s fingers moved unconsciously, as if tracing lines in the air.

“What if we made them think we had… three hundred rifles,” he said. “Four hundred. What if every time a head appears, it gets shot from a different place, even if it’s just one man pulling the trigger?”

Vinogradov frowned.

“What are you talking about?” he asked.

“A trick,” Nikolai said. “A six-rifle trick.”

The argument started quietly.

And then it didn’t.

“You want to do what?” Petrov said, voice rising.

Nikolai stood in front of the pile of spare rifles, holding one up.

Its stock was cracked, but its barrel was straight.

Its bolt, with a little cleaning, would slide.

“I want to take six rifles,” he said. “Maybe more, if we can make them work. I want to set them up on the flanks and rear of our position. On tripods, on tied branches, on mounds. I want to be able to fire them from a distance. All of them. Myself.”

Petrov stared.

“That is the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard,” he said.

Volkov rubbed his forehead.

“Explain,” he said. “Slowly.”

Nikolai knelt and set the rifle on the floor.

He used his hands as if drawing on the dirt.

“Here is our trench,” he said. “Here is the tree line where they will gather. Our men are here. When the Germans attack, they will be listening as much as seeing. If they hear one rifle, from one place, they will mark it. They will say, ‘Here is their sniper. Here is their line.’ They will concentrate fire. They will push through.“

He moved his hand.

“But if, when they attack, they hear rifles from here…”—he tapped one spot—“and here…”—another—“and here… and each time they lose a man, it seems to come from a different angle… what will they think?”

Vinogradov’s eyes shifted.

“That there are many of us,” he said slowly. “That they are walking into an ambush.”

“Exactly,” Nikolai said. “I can set up rifles at fixed angles, pre-sighted on likely paths of advance. I can rig them with strings, wires, anything that lets me fire without being at the stock. Six rifles. Six different mouths of fire. They will think they are coming under attack from a company of snipers.”

Petrov snorted.

“You would waste six rifles on a parlor trick,” he said. “When we barely have enough to arm our men?”

“Those rifles are not in men’s hands now,” Nikolai said. “They are broken, yes, but not beyond use. A cracked stock can be strapped to a log. A sticky bolt can be oiled and worked once or twice. I’m not asking for their best weapons. I am asking for the ones you’ve already written off.”

Petrov opened his mouth.

Volkov held up a hand.

“And you think,” the captain said carefully, “that you can manage this alone? Fire six rifles, in different places, at different times, while also staying alive?”

Nikolai nodded.

“I can place them so the strings run back to one slit trench,” he said. “Mine. I can fire one, then another, then another. I can move between them. If I hit a few men every time they try to advance, from different directions, it will slow them. Confuse them. Make them think twice.”

“You cannot guarantee hits with rifles fired by strings,” Petrov snapped. “Our doctrine emphasizes accurate fire, not theater.”

“Our doctrine also emphasizes surviving to carry out our mission,” Volkov said mildly.

Petrov turned on him.

“You cannot seriously be considering this,” he said. “He will be taking weapons from the repair queue, diverting effort that could go to strengthening our line. For what? Some circus trick?”

Nikolai kept his voice calm.

“I have watched the way they move,” he said. “They count shots. They look for patterns. Today, every time I repositioned, they adjusted quickly. Tomorrow, if we do not sow confusion, they will notice how thin our fire is. They will press. And when we are out of bullets…”

He let that hang.

“Have faith in the men,” Petrov said. “They will fight to the last.”

“I know they will,” Nikolai said softly. “I have watched them. That is why I would like to give them more than faith.”

The room went quiet.

Volkov looked between them.

Between Petrov’s stiff anger and Nikolai’s steady gaze.

Then he made his decision.

“Do it,” he said.

Petrov’s head snapped toward him.

“What?” he demanded.

“Do it,” Volkov repeated. “Antipov, give him six rifles. Ones we don’t expect to get back in perfect condition anyway.”

Antipov shrugged.

“I can find six that will shoot,” he said. “If he doesn’t mind ugly.”

“I don’t mind ugly,” Nikolai said.

Petrov slammed his fist lightly on the edge of the table.

“This is a waste,” he said. “A selfish misuse of comrades’ weapons.”

Volkov’s jaw hardened.

“No, Comrade Petrov,” he said. “Selfish would be keeping every weapon in the same place, firing in the same pattern, and then dying bravely when the enemy understands exactly how thin we are. This is a gamble, yes. But we are already gambling with our lives. I prefer to choose the terms when I can.”

Petrov’s nostrils flared.

“I will note this decision in my report,” he said.

“Do that,” Volkov said. “And if we survive tomorrow, we can all argue about it with the division chief of staff. If we don’t… the report won’t matter much.”

Petrov’s jaw clenched.

He stood abruptly.

“Do as you wish, then,” he said.

He snatched his cap and left the room, the door slamming behind him, letting in a blast of cold air.

The others exhaled.

Volkov looked at Nikolai.

“You’d better make this trick of yours work,” he said. “I just picked a fight with a zampolit over it.”

Nikolai’s mouth quirked, just a fraction.

“I will do my best, comrade captain,” he said.

“Your best had better be very good,” Volkov said.

Night came early at that latitude.

By the time the wounded had been carried further back, rations distributed, and sentries posted, the sky was already a deep, blue-black bowl over the frozen world.

Nikolai spent every minute before full dark working.

Antipov produced six rifles.

Two had cracked stocks.

One had a bent front sight he straightened with a pair of pliers and a little hammering.

Another had a bolt that stuck; Nikolai worked it until it slid.

A fifth was a captured Mauser, its wooden stock scuffed, its action smooth.

“Magazine-fed,” Antipov said. “More chances before you have to touch it.”

The sixth was an older Mosin, the bluing worn.

“Six rifles,” Nikolai murmured. “Six mouths.”

He wrapped each in cloth to muffle clinks and carried them out one by one into the frozen night.

He knew the terrain around the hill better than anyone.

He’d crawled through every thicket, every clump of dead grass, every shallow fold in the ground, looking for positions, for paths, for angles.

Now, he used that knowledge differently.

On the left flank, halfway down the slope, he found a low mound of earth with a shattered tree stump jutting from it.

He lashed one rifle to the stump, stock against the wood, barrel poking through a gap between broken branches.

He carefully aimed it at a stretch of ground he’d seen Germans use as a covered approach that afternoon.

He wedged stones under the barrel until the sight picture matched the memory in his mind.

Then he tied a cord to the trigger, ran it back through the brush, and looped it along the ground toward a shallow scrape near the crest of the hill.

On the right flank, he did the same, finding a cluster of rocks that made a natural rest.

Another rifle.

Another string.

In a small depression behind the main trench, he set up the captured Mauser, its scope glinting faintly; he dulled it with soot from the chimney.

He made sure each rifle was protected from the wind as best he could, wrapped with rags where they touched cold metal.

He loaded each with a single round at first, then tucked spare cartridges nearby, in little piles, protected under bits of tarp.

He knew he might not have time to reload them all.

But he also knew that if he got lucky, if he had a moment, he’d want more shots.

By midnight, his hands ached from cold and work.

But the network was laid.

Six rifles.

Six strings.

All of them ran back, eventually, to a narrow dugout he’d carved for himself at the highest point of the hill, where a small rock outcropping jutted above the trench line.

From there, he could reach each cord.

From there, he could watch.

From there, he could pull.

When he crawled back into the farmhouse briefly to warm up, Petrov was sitting by the stove, writing in a notebook.

He looked up as Nikolai entered, eyes flinty.

“Enjoy playing with your toys?” Petrov asked.

Nikolai shrugged.

“We will see in the morning if they are toys,” he said.

Petrov’s lips thinned.

“Remember,” he said, “if your trick fails, there will be no excuses. Only graves.”

Nikolai met his gaze.

“If my trick fails,” he said quietly, “we will all be too busy being dead to argue about it.”

He left Petrov there, ink scratching on paper, and went back out to his hill.

Dawn came gray and slow.

Nikolai lay on his stomach in his little scrape, breath forming a steady cloud in front of his face.

He had his own rifle next to him, its scope caps closed to keep frost off the glass.

Around him, the six cords lay like thin, frozen snakes on the ground.

Each was tied to a trigger somewhere on the hill.

He could feel them under his gloved fingertips.

Down in the main trench, men muttered, coughed, cleared their weapons.

Volkov walked the line, speaking quietly to each squad.

“Remember,” the captain said. “Hold your fire until you have a clear target. Don’t waste bullets on shadows. Let them come close, then make it count.”

Petrov followed, watching.

When he reached Nikolai’s position, he stopped.

“You really think you can fire all six?” he asked.

“I don’t need them all at once,” Nikolai said. “Just enough to make them hesitate.”

“And if they don’t?” Petrov asked.

“Then I will do what I can with the one in my hands,” Nikolai said.

Petrov looked as if he wanted to say something more.

Then, unexpectedly, he sighed.

“I hope, for all our sakes,” he said, “that your… creativity… is as effective as you believe.”

He moved on.

Nikolai turned his attention back to the tree line.

Mist hung low over the frozen ground.

Snow crunched faintly as figures moved among the trees.

He couldn’t see them yet.

He could feel them.

He closed his eyes for a heartbeat.

He tried to remember the crow.

The stillness before the shot.

The way the world narrowed to a single line between his eye and the target.

When he opened them, the fog seemed thinner.

Shapes emerged.

German soldiers.

Dozens.

Then hundreds.

They gathered at the tree line, dark shapes against the frost.

He saw officers moving among them, pointing, waving.

He saw machine guns being set up.

Mortar tubes.

He checked the positions he’d chosen.

The left flank riffle was aimed at a shallow fold where their left assault group would likely advance.

The right flank covered a gully.

The Mauser in the rear covered a path they might use to flank if they thought the main line was weak.

The other three rifles covered spots in front of the trench where he expected them to go to ground.

He breathed.

He waited.

From the German side, a shrill whistle.

Then another.

The line moved.

Men stepping out of the trees, spreading into assault waves.

Rifles.

Submachine guns.

Some carrying satchel charges.

From the Russian trench, someone muttered a prayer.

Volkov’s voice, calm: “Hold… hold…”

Nikolai watched through his scope now, using his own rifle for the first shot.

He picked a German NCO near the front, shouting and waving his men forward.

He exhaled.

The rifle cracked.

The NCO dropped.

A brief hesitation in that group.

Shouts.

Then they surged again.

He slid the bolt, chambered a new round, and shifted slightly.

Picked another.

Crack.

Another man down.

German machine guns opened up, stitching the ridge line.

Snow and dirt spat up along the trench.

The battalion’s own machine guns answered, their slower, heavier rhythm underlining the higher staccato of individual rifles.

Nikolai saw one of the Germans in the left-hand wave break into a run, head low, aiming for the fold in the ground he’d marked the night before.

He let his own rifle rest.

His left hand found the first cord.

He pulled.

Fifteen meters away, hidden by brush and snow, the first borrowed rifle bucked, its muzzle flash brief.

Downrange, the German jerked and fell face-first.

The ones nearby dropped, scrambling for cover.

“Sniper!” someone shouted—in German, but Nikolai knew the word in any language.

He heard their officers yelling.

His fingers moved to the second cord, running toward the right.

A different group, on the right flank this time, was moving in bounds.

One of them popped up from behind a low mound to sprint.

The cord tightened under his hand.

He pulled.

The second rifle fired.

The angle and distance were just right; the bullet caught the runner mid-stride.

He collapsed, sliding in the snow.

From the German perspective, two shots had just come, in quick succession, from two very different directions.

Their advance slowed.

Not stopped.

But slowed.

Men looked around, trying to spot muzzle flashes.

Trying to guess where the Putin (Russian slang) was.

They saw the ridge.

The main trench.

They didn’t see the stump or the rocks or the little depression where an ugly, half-broken rifle sat lashed to a log.

“Faster,” Volkov called. “Keep shooting! Don’t let them get too close!”

The line obeyed, but it was measured.

Ten rounds here.

Five there.

Men firing only when they saw shapes, not just movement.

Nikolai saw three Germans dive into a shallow hollow he’d predicted, thinking they were out of the main line’s fire.

He switched cords.

The third rifle, on the middle slope, had its muzzle pointed at that hollow.

He pulled.

The shot kicked up snow.

Off by a hand’s width.

He adjusted the cord, pulled again.

This time, one of the three jerked backward.

The others froze.

They’d been shot from above and slightly to the side—different again.

The impression he wanted wasn’t of one invisible marksman.

It was of many.

Many, many.

“Where are they?” he imagined them shouting.

Nikolai smiled grimly.

He knew exactly where he was.

They didn’t.

That was the whole point.

—

The Germans pressed.

They were professionals.

They’d faced snipers before.

They told themselves this was merely the usual.

They kept moving.

But the ground in front of the Soviet trench began to sprout more prone shapes than advancing ones.

Every time they tried to form up another wave, another man near the front would drop, his helmet spinning, his body crumpling.

Sometimes it was Nikolai’s own rifle.

Sometimes it was one of the six others, triggered by a yank of cord at just the right moment.

On the flank, a small group attempted to use a gully he hadn’t anticipated.

He saw them by chance—shadows where there should have been none.

He couldn’t shift a fixed rifle that quickly.

So he used his own.

Crack.

The point man fell.

The others dropped.

They hesitated.

Hesitation, he knew, was almost as valuable as death.

It bought time.

Time for his own men to reload carefully instead of desperately.

Time for the machine gunners to swap barrels.

Time for men whose weapons had jammed to clear them.

On the German side, the battalion commander—a major with a red scarf tucked under his collar—cursed behind a tree.

“This is nonsense,” he growled to his aide. “Their line is thin. Our patrols reported little movement. Yet every time we advance, we lose men as if they have an entire company of snipers.”

His aide glanced nervously at the ground, littered with dark shapes.

“Do we call artillery?” the aide asked.

The major hesitated.

They had mortars.

They had a battery of field guns further back.

But ammunition was not infinite.

High command expected results, not excuses.

“If we call artillery, they’ll say we asked for steel to finish a job infantry should have done,” the major muttered. “Assault again. Left and right concurrently. Find their shooters.”

He stood up, waving.

“Forward!” he shouted. “They are only men! They bleed!”

He was right.

They were only men.

They did bleed.

He wasn’t counting on the fact that some men on that hill had learned to make their thirty bullets sound like three hundred.

—

The second wave came in thicker.

Mortar shells crumped around the hilltop.

Shrapnel hissed.

A machine gun position two foxholes down from Nikolai vanished in a rain of dirt and wood.

Screams followed.

A runner came scrambling up the trench, eyes wild.

“Machine gun down!” he shouted to Volkov. “Third squad is low on ammo! Fourth lost their section leader!”

Volkov swore.

“Tell them to fall back to the reserve line if they’re hit too hard,” he said. “No use dying in a crater if you can still shoot from five meters back.”

The runner dashed off.

Petrov hovered nearby, face pale now, notebook abandoned.

“Comrade captain,” he said tightly, “they are pushing on the right!”

“I can see that,” Volkov snapped, glancing that way.

The right-hand flank rifle Nikolai had set up was doing what it could.

He saw a German aiming a grenade at a cluster of his comrades.

He yanked the cord.

The improvised shot hit the grenade-thrower in the shoulder.

The grenade flew instead at a shallow angle, landing short.

It exploded among his own advancing men.

Confusion.

More shouting.

“Who is doing that?” Petrov demanded, as if accusing someone in the trench.

Nikolai didn’t answer.

He didn’t have breath to spare.

His fingers were moving faster now.

Left.

Right.

Center.

His own rifle barking in between.

Sometimes he hit cleanly.

Sometimes he missed.

But every shot from a new angle made the Germans flinch in a new direction.

Their major finally cursed and grabbed the radio handset.

“Artillery,” he barked. “On the hill. Full barrage. They are infested with snipers.”

On the Soviet side, Vinogradov heard something similar in his own headphones.

Artillery—what was left of it—checking in.

“We have a few shells we can spare,” the battery commander said. “Where do you want them?”

Vinogradov looked at the map.

At the hill.

At the Germans.

At Volkov.

“We’re too close to call it on their heads,” he said. “It would hit us as much as them.”

Volkov nodded grimly.

“Save it,” he said. “If they break through, drop it on our own positions after we’ve fallen back. Better craters than graves.”

Petrov stared at him, aghast.

“You would call fire on our own hill?” he demanded.

“If it keeps them from rolling over us and using this ground to move deeper,” Volkov said, “yes.”

Argument sparked again.

“Unbelievable,” Petrov said. “You rely on the trick of one man with six rifles and plan to shell your own troops—”

“And yet,” Volkov said, “we are still here.”

All three men turned instinctively as a German officer stood, blew a whistle, and waved another wave forward.

Another fifty men.

Maybe more.

Their helmets ducked.

Feet pounding.

“Someday,” Volkov muttered, “they will run out of courage. Or people. Or both.”

Nikolai didn’t answer.

He was too busy.

—

By late morning, the battalion’s ammunition was truly low.

Men had resorted to collecting cartridges from the dead and wounded.

Some had picked up German weapons.

Snow turned gray-brown in patches where men had fallen and been dragged back.

The German assault had slowed.

Not stopped.

Slowed.

Casualties had piled up in front of the hill.

Ragged lines of bodies, sprawled, frozen in strange positions.

The six-rifle trick had not killed them all.

No trick could.

But the impression it created—that there were snipers everywhere on that slope—had forced the German commander to pause, to regroup, to reconsider each push.

He’d lost more men than he’d budgeted.

He was starting to think like a man who might have to explain himself.

At one point, he ordered a flanking maneuver around the right, through a copse of trees he believed to be unguarded.

Nikolai’s Mauser, lashed in that small depression behind the Soviet line, had a different opinion.

Crack.

One German fell.

Crack.

Another.

From their perspective, it felt like they’d stumbled into yet another nest of shooters.

“Do they breed in the snow?” one of them shouted bitterly, ducking.

In truth, it was still one man.

One man, six rifles, thirty fingers of cord.

And his own weapon.

His shoulder ached.

His hands were numb.

His eyes burned from staring through glass and down sights all morning.

But he kept moving.

Cord.

Trigger.

Bolt.

Sight.

Breath.

Fire.

What he would remember later, more than the shots, was the feel of those cords under his hands.

Taut lines between him and the barrels spread across the hill.

Every pull a choice.

Every choice a life, or not.

At last, around midday, the Germans wavered.

Their major, his red scarf darker now with mud and something else, stared through his field glasses at the hill.

His battalion had taken losses approaching thirty percent.

His assault platoons were shadows of their morning strength.

Each time they tried to mass for one more push, fire came from unexpected angles.

From the left.

From the right.

From somewhere behind his own perception of the line.

“Enough,” he said hoarsely.

He slammed the butt of his hand against a tree.

He was not a monster.

He cared about his men, as much as anyone.

He could not justify spending them on a hill that seemed to have far more defenders than his intelligence reports had suggested.

“Pull back,” he ordered. “We will hold them in place and wait for orders. Let artillery and higher-ups decide how badly they want that hill.”

His aide looked relieved.

Some of the remaining men did too.

They began to drift back into the tree line.

Slowly, carefully, covering each other, watching for those invisible flashes of fire.

The Soviet soldiers in the trench watched them go.

Their fingers, cramped, did not relax yet.

“This could be a feint,” Petrov warned.

“Maybe,” Volkov said.

He didn’t quite believe it.

He knew retreat when he saw it.

Nikolai watched through his scope until the last helmet vanished.

He didn’t fire at their backs.

No need.

No ammunition to spare, either.

His world, which had narrowed to reticles and cords and trigger pulls, expanded again.

He became aware of his own body.

Of the pounding in his temples.

Of the ache in his shoulders.

Of the way his fingers were bleeding under the gloves where the cords had rubbed skin raw.

He realized he was smiling.

Very, very faintly.

He stopped.

“Any word from regiment?” Volkov called to Vinogradov.

The artillery officer listened to his headset, then nodded.

“They’ve begun their own attack on the German flank,” he said. “Our job was to hold. They say we’ve done it.”

Volkov closed his eyes for a second.

Then opened them.

“Count casualties,” he said. “Gather ammunition. Mark the wounded. And for the love of God, get those men some hot water if we have any.”

Men moved.

Slowly.

Stiffly.

Like puppets whose strings had been cut.

Petrov approached Nikolai’s position as he rolled onto his back, staring at the colorless sky.

“You did it,” Petrov said.

It wasn’t quite admiration.

But it wasn’t contempt, either.

Nikolai turned his head.

“We did it,” he said.

“Your trick,” Petrov said, glancing at the spread of cords. “It worked.”

Nikolai shrugged.

“It didn’t bring anyone back,” he said. “But it kept more from joining them, maybe.”

Petrov looked down the slope.

At the shapes in the snow.

At the distance.

“How many?” he asked quietly.

Nikolai frowned.

“What?” he said.

“How many did you kill?” Petrov asked.

Nikolai thought.

He thought of each shot he was certain had hit.

The man in the fold.

The grenadier.

The NCO.

The runners.

The ones in the hollow.

Recollections layered over recollections.

“Around forty with my own rifle,” he said slowly. “The six others, I don’t know. Two hundred shots, maybe. Many misses. Many… not.”

Petrov stared.

“You must know,” he said.

Nikolai shook his head.

“I am not the one who counts,” he said. “You are.”

Petrov swallowed.

He nodded slowly.

“We’ll estimate for the report,” he said. “From the ground. From blood. From positions. Battalion says—already—that preliminary counts show at least 225 Germans killed in front of our line.”

“225,” Nikolai repeated softly.

He didn’t feel pride.

He didn’t feel guilt exactly, either.

He felt… empty.

And tired.

Petrov hesitated.

“You disobeyed doctrine,” he said. “You took weapons from the repair pile without properly documenting them. You diverted energy. You argued with your political officer.”

Nikolai stared at him.

“Do you intend to arrest me?” he asked, tone mild.

Petrov’s lips twitched.

“No,” he said. “I intend to write your name into the part of the report that will be sent up. Along with that number.”

Nikolai frowned.

“What for?” he asked.

“For morale,” Petrov said. “You were right earlier. Numbers do matter. Stories do matter. The men will fight better knowing someone up there can make a few bullets sound like many. The people back home will sleep better knowing that tricks and courage still work.”

Nikolai’s eyes narrowed, just a little.

He’d seen what the papers did with men like Zaitsev.

Turned them into symbols.

Symbols that could be heavy to carry.

“I’m not interested in being in your stories,” he said.

Petrov studied him.

“Perhaps not,” he said. “But your battalion might be interested in the food that comes with a commendation. Or the extra ammunition. Or the medical supplies. You saved them today. Let the story do something for them tomorrow.”

That made Nikolai pause.

He thought of the men in the trench.

Of Eddie—no, that was the other front—of Sasha, with the big nose and bad jokes.

Of Yura, who still wrote letters to a girl in Minsk he hadn’t seen in two years.

Of Petrenko, who sang softly under his breath when artillery fell.

He sighed.

“Write whatever you like,” he said. “As long as they get something from it.”

Petrov nodded.

“You have my word,” he said.

“As a political officer?” Nikolai asked dryly.

“As a man who was just as interested in seeing the sun today as you were,” Petrov replied.

For the first time since they’d met, Nikolai saw something in Petrov’s eyes that wasn’t calculation.

Fear, maybe.

Relief.

Shared.

The argument, which had started bitterly in the night, had shifted.

They were no longer on opposite sides of a theoretical doctrine.

They’d stood on the same hill.

Under the same mortar shells.

Sometimes, that changed people.

Sometimes, it didn’t.

Today, it had.

After the battle, during a lull in the front, an officer from division came to inspect the positions and take statements.

He wore a long coat, its collar up, and had the clipped manner of someone who would be writing a report on people who might never read it.

He asked questions.

He wrote down names.

He tallied ammunition.

“Your battalion commander reports that this hill was held against repeated attacks,” the officer said to Volkov. “That casualties were high but acceptable. That the enemy suffered… considerably more.”

“Yes, Comrade Major,” Volkov said.

“And he says,” the major went on, “that one of his snipers improvised a method using six rifles to produce the effect of a larger force. Killing… two hundred twenty-five of the enemy and causing confusion.”

Nikolai shifted uncomfortably nearby.

The major turned his gaze on him.

“You are Sokolov?” he asked.

“Yes, Comrade Major,” Nikolai said.

“You came from where?” the major asked. “Before the war.”

“From Sverdlovsk oblast,” Nikolai said. “Village of Novaya Reka.”

“Hunter?” the major asked, as if ticking off a stereotype.

“Yes,” Nikolai said.

The major nodded.

“Good,” he said. “Hunters understand patience. And tricks.” He gestured toward the hill. “Show me.”

Nikolai walked him to the positions.

Showed him the stump.

The rocks.

The little depression.

The cords, frayed and tinged with dried blood.

The rifles, now cool and empty, their barrels marked by the day’s work.

The major listened.

He didn’t interrupt.

When Nikolai finished, the major stood for a moment, looking down the slope.

At the shapes that had been hastily buried in shallow graves.

At the ground, scuffed and stained.

“Commander of the enemy unit reported to have pulled back?” he asked.

“Prisoners say he was furious,” Volkov said. “He demanded to know who had filled the hill with snipers. Some of his men told him they’d only seen one sometimes. They fought about it.”

The major snorted once.

“We will not be putting that part in the official account,” he said.

He turned to Nikolai.

“You understand that some will say you wasted resources,” he said. “That those six rifles might have been better used in six other hands.”

“Yes,” Nikolai said.

“Others will say you used what was already almost lost to change the shape of the battle,” the major continued. “That you took broken things and made them bite again. That’s a story worth telling.”

“I didn’t do it for the story,” Nikolai said.

The major’s mouth twitched.

“Good,” he said. “The ones who do,” he added, “tend not to survive long.”

He tore a sheet from his notebook, scribbled something, and handed it to Volkov.

“Recommendation for award,” he said. “Medal… we’ll see. Higher-ups like big numbers. ‘225 enemy dead from one man’s sector’ will make them sit up.”

Volkov nodded.

“Yes, Comrade Major,” he said.

The major glanced at Petrov.

“And you approve?” he asked the zampolit.

Petrov held his gaze.

“I… had doubts,” he said. “I still worry about deviation from doctrine. But when the doctrine runs out of bullets, one must improvise. He kept our men alive. That is loyalty to the Motherland in another form.”

The major seemed satisfied.

He left with his notebook.

Life on the hill moved on.

Orders came.

Orders changed.

The battalion was rotated back, then forward again.

Spring came, in muddy, reluctant fits.

The war moved west.

Years later, when the war was long over and Soviet uniforms had changed colors and shapes, when new slogans had been painted on walls and old ones quietly scraped off, an old man with a lined face stood in a small apartment in Sverdlovsk oblast and watched his grandson play with a toy rifle.

The boy, eight years old, made pew-pew noises, hiding behind a chair.

“Enemy, Dedushka!” the boy said. “Over there!”

Nikolai Sokolov—white-haired now, his back stiff, his fingers twisted a little from old cold—smiled faintly.

“Is that so?” he said. “How many?”

“Lots,” the boy said. “But I have many rifles.” He puffed out his chest. “Like the story.”

The story.

It had come back to his village in a newspaper printed decades ago, in faded ink. People had copied it. Passed it around.

Sniper Sokolov’s Six-Rifle Trick Stops German Battalion, Saves Position.

225 Fascists Sent To Their Graves by One Man’s Ingenuity.

It sounded more heroic in print than it had felt in his frozen hands.

He’d never corrected it.

What was the point?

You couldn’t explain in a paragraph how your fingers had bled.

How some of the shots had missed.

How some of the men who survived that day had died a week later, or a month, or at Kursk, or outside some nameless village no one remembered.

You couldn’t print the way Petrov’s face had changed when he’d seen the hill in the morning and understood that sometimes, breaking small rules to keep larger ones was not a sin.

You couldn’t put into neat columns how complicated during war the word “saved” really was.

He shuffled over to the cupboard.

On the top shelf, wrapped in a cloth, he kept an old scope.

The rifle it had been mounted on was long gone—left behind in some army storehouse or cut up to make room for newer designs.

But he’d kept the glass.

He took it down, unwrapped it, and handed it to his grandson.

“What’s that?” the boy asked.

“A way of seeing differently,” Nikolai said.

The boy lifted it to his eye.

“Oh!” he said. “It makes things big!”

“It makes you choose,” Nikolai said softly. “What you look at. What you don’t.”

The boy frowned, not quite understanding.

“You killed two hundred twenty-five Germans with six rifles,” the boy said. “Papa says so. He read it in the book.”

“Papa shouldn’t believe everything he reads in the book,” Nikolai said, but there was no heat in it.

“Did you?” the boy pressed.

“I helped my comrades stay on a hill until someone bigger than us decided to fight over it,” Nikolai said. “That is what I did.”

“Is that yes?” the boy asked.

Nikolai smiled.

“It is the answer you get,” he said. “When you are old enough, you will learn that not every question has a simple yes or no.”

The boy looked back through the scope, turning, making his grandfather’s face large, then small.

“Why did you use six rifles?” he asked.

“Because I didn’t have seven,” Nikolai said dryly.

The boy giggled.

“And because,” he added more seriously, “sometimes it is not how much you have, but how the enemy thinks you have that matters.”

The boy nodded slowly, as if absorbing something that would make more sense later.

“Do you still hate them?” he asked quietly, surprising Nikolai.

“The Germans?” Nikolai asked.

“Yes,” the boy said.

Nikolai looked out the window.

At the birch trees.

At the snow, thinner now, but still there in patches.

At the sky, which had long since stopped echoing with guns.

“I don’t think about them much anymore,” he said. “I think about the ones next to me on the hill. The ones whose names are on the stone in town. Hate is heavy. Ingenuity is lighter.”

The boy thought about that.

“Grandma says you saved your battalion,” he said.

Nikolai hesitated.

He remembered Volkov’s hand on his shoulder.

Petrov’s signature on the recommendation.

The major’s rough nod.

The way men on that hill had looked at him differently afterward.

As if he’d been more than just the quiet one with the good eye.

As if he’d somehow become something larger.

He’d never felt larger.

He’d felt… small.

And tired.

And grateful.

And guilty.

All at once.

“I did what I could with what I had,” he said. “That’s all any of us ever does.”

The boy lowered the scope.

“Can you show me how to shoot?” he asked.

Nikolai laughed softly.

“Not today,” he said. “Today, we eat. Your grandmother has made soup. Tomorrow, perhaps. First, we learn to breathe.”

“Breathe?” the boy asked.

“Yes,” Nikolai said. “You breathe first. Then you shoot. Not the other way around.”

He thought of the crow.

Of the hill.

Of the cords under his fingers.

Of the thin line between being called a hero and being another name on a stone.

His grandson nodded, solemn.

“Okay,” the boy said. “We breathe.”

Nikolai patted his shoulder.

“Good,” he said.

Outside, the birch trees stood, white and quiet.

No rifles.

No cords.

No shapes in the snow.

Just the wind.

And, faintly, somewhere deep in the old man’s memory, the echo of six rifles and one more, speaking with a single voice across a frozen field on a morning no one would ever fully put into words.

THE END

News

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six Hours Later, His Lone Gamble Turned Their Mockery into Shock, Freedom, and a Furious Argument in the War Room

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six…

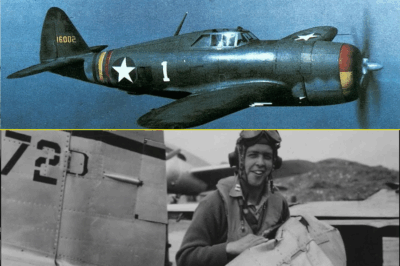

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That Weight Into a Weapon and Sent 3,752 Luftwaffe Fighters Plummeting From the Sky

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That…

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion, Claimed Ninety-Six Enemy Combatants Without a Single Direct Shot, and Sparked One of the War’s Most Tense Command Arguments

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion,…

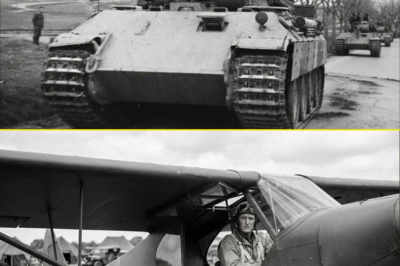

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane, Dove Through Fire, and Knocked Out Six Panzers to Save 150 Men

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane,…

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to Notice — But What He Saw, What He Asked, and the Argument That Followed Changed the Boy’s Entire Life Forever

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to…

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet Single Dad Janitor Stood Up, Walked to the Defense Table, and Changed Everything

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet…

End of content

No more pages to load