He Wore the Swastika on His Sleeve While Stitching Wounds at the Front, But in an American POW Camp a ‘Shocking’ X-Ray Forced a Nazi Army Surgeon to Question Everything He’d Been Proud to Believe

The first time Dr. Ernst Brandt operated under fire, he’d thought medicine was the one decent thing left in the mess he’d helped create.

It was 1942, on the Eastern Front. The field hospital had been a sagging canvas tent that smelled of mud, blood, and disinfectant, pitched far enough behind the lines that artillery sounded like distant thunder—until a shell fell short and punched a ragged hole through the far wall.

The wounded kept coming anyway.

“Another one, Herr Oberarzt,” the orderly had said, pushing a stretcher through spattered snow. “Shrapnel to the abdomen.”

Ernst had washed his hands in water that turned pink, pulled on stiff rubber gloves, and leaned over the table. A boy’s face looked up at him—eighteen, maybe. The kind of face propaganda posters used, all sharp jaw and bright eyes.

“Name?” Ernst had asked, more out of habit than necessity.

“Schmidt,” the boy had whispered. “I don’t want to die.”

“You won’t,” Ernst had lied, because that was what you said.

He’d cut. Tied off. Removed fragments. Worked by kerosene light with mortar thumps in the background. For hours that bled into days, he’d lived in that space between life and death, between orders and instincts.

He told himself that whatever madness raged above ground, on the maps, in speeches, he was at least doing something human: keeping men alive.

It was a comforting thought.

He held onto it all the way through winter, through retreat, through the collapsing front. He held onto it, even, when the division surgeon pressed a paper into his hand and said, “New directive. Priority for operating goes to those with the best chance of returning to combat. You understand, Brandt?”

“I am a doctor,” Ernst had said.

“You are an army doctor,” the surgeon had corrected. “Our oath is to the Fatherland first.”

Ernst had signed the directive anyway.

He knew where that put him. Somewhere between healer and accomplice. He just hoped the scales tipped the right way.

He still thought that was possible the day the war spat him out into an American POW camp.

He woke to the smell of soap and coffee.

For a moment his brain insisted on mud and kerosene, the taste of iron in the back of his throat. Then the light changed when he opened his eyes—clean, white, too bright.

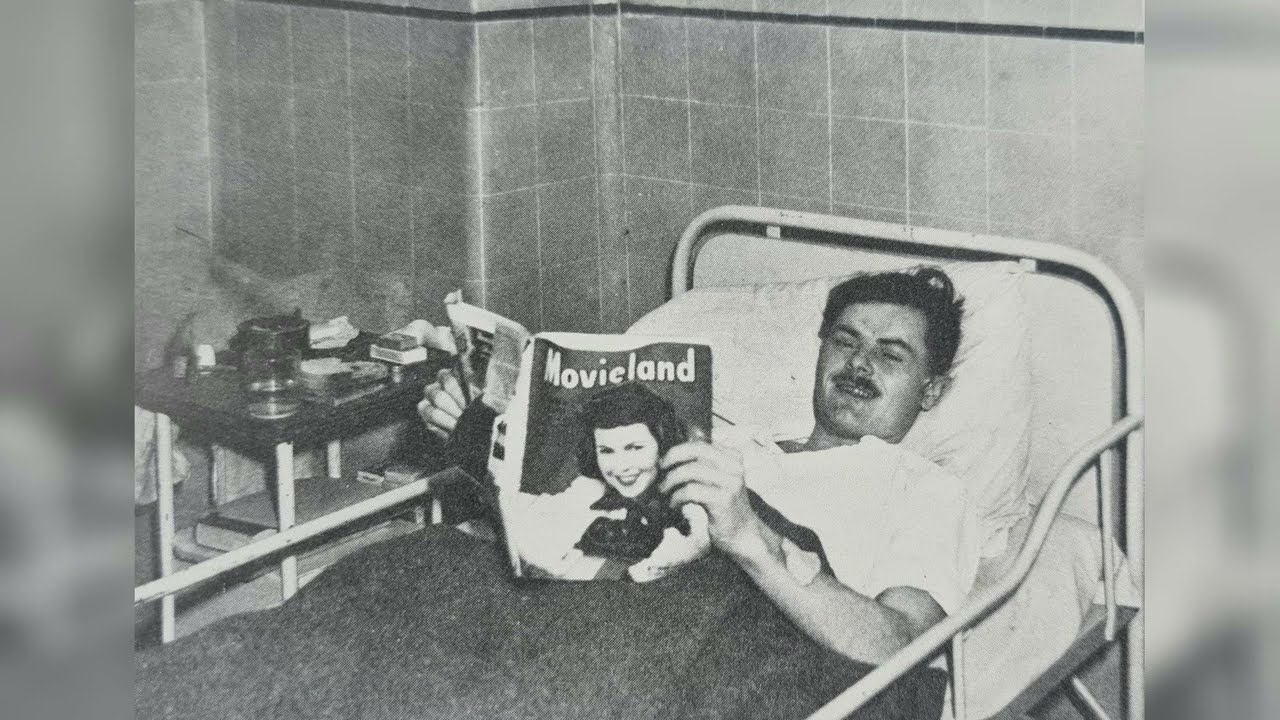

He lay in a narrow bed with crisp sheets, a blanket that actually covered his feet, and a bandage around his ribs that did not itch.

Disoriented, he tried to sit up. Pain stabbed under his left side. A hand appeared, firm but not rough, pressing his shoulder down.

“I wouldn’t do that yet,” a voice said in accented German. “You’ll pop your stitches. And after all the trouble I went to, that would make me very cross.”

Ernst turned his head.

The man standing beside the bed wore a clean khaki uniform with captain’s bars and a stethoscope slung around his neck. His hair was dark, cropped short. His eyes were tired but clear.

An American.

Ernst’s hand twitched toward his chest, searching for the rank insignia that were no longer there. His sleeve was plain. POWs didn’t rate decorations.

“Where…?” he rasped.

“Camp Ashford,” the American said. “Somewhere in France. Don’t worry, your geography will catch up. You took some shrapnel when your column ran into a bit of resistance. Our medics patched you up in the field, and I had the pleasure of finishing the job.”

He pulled a small X-ray from a folder and held it up to the light. Ernst’s own ribs glowed pale, a darker shard lodged between two shadows.

“See?” the American said. “Nasty angle, but it missed anything truly important. You’re a lucky man.”

Lucky.

The word jarred.

“Why?” Ernst asked.

The American frowned. “Why what?”

“Why treat me?” Ernst said. “I am your enemy.”

He expected the man to scoff, or to say something about the Geneva Conventions like a child reciting catechism.

Instead, the American shrugged.

“You’re my patient,” he said. “Everything else is someone else’s department.”

It shouldn’t have shocked Ernst. He knew, intellectually, that the Allies claimed to treat prisoners humanely. He’d seen pamphlets dropped by enemy planes, full of smiling POWs eating decent food.

Propaganda, he’d thought.

Now he was lying in a bed inside that propaganda, and the sheets were clean.

The American extended a hand. “Captain Michael Harris,” he said. “US Army Medical Corps. And you are…?”

“Dr. Ernst Brandt,” Ernst said automatically. “Oberstarzt, German Army.”

Harris whistled softly.

“A colonel,” he said. “Fancy. They must have been running out of doctors to put you that close to the fighting.”

Ernst didn’t answer. The old reflex to straighten under mention of rank fought with the new reality that his collar was bare and he was, by any measure, defeated.

His gaze flicked to the small table by the bed. A metal cup of water. A loaf of bread on a tin plate. No one standing guard with a rifle.

“If you’re expecting to be beaten,” Harris said dryly, “you’re going to be disappointed. I have enough work without adding war crimes.”

The word landed like a stone.

War crimes.

They’d whispered about trials in camp, about tribunals somewhere across the Channel. They’d joked, nervously, about hanging lists. No one thought it would touch them. That was for the big men. The ones in cities. The ones who gave speeches.

Ernst cleared his throat.

“Thank you,” he said stiffly.

“You’re welcome,” Harris said. “Drink. Eat. You’ll be on your feet in a few days. And when you are, we could use your hands.”

Ernst blinked. “What?”

Harris smiled faintly.

“You’re a surgeon,” he said. “I’m a surgeon. We have hundreds of POWs and only so many American staff. Geneva says we’re supposed to care for you lot. I say we might as well let you help.”

He tapped Ernst’s chart with two fingers.

“Relax,” he added. “We won’t give you scalpels until you stop listing sideways when you stand.”

He left with the X-ray under his arm, whistling some tune Ernst didn’t recognize.

Ernst stared at the ceiling.

He had expected captivity to be a humiliation. Hunger. Boredom. Guards with tight jaws and tighter trigger fingers. He had not expected… decency.

For a man who had spent years being told that the enemy was barbaric, it was a disorienting thought.

He told himself not to read too much into it.

It was just one doctor. One ward.

The world was still the world.

The camp hospital was a long, low, wooden building with windows that could be shuttered in an air raid and opened when the air got too thick inside. The floors were scrubbed so often they smelled permanently of soap. The beds were arranged in orderly rows, American wounded on one side, German POWs on the other.

The first time Ernst stood there in clothes that weren’t his own (drab camp-issue tunic, no rank), he felt like a ghost in someone else’s story.

Harris had thrust a white coat at him.

“Here,” he said. “This will make you look less like a patient and more like a colleague. Maybe even scare the guards into being polite.”

“I am your prisoner,” Ernst said.

“You’re my assistant,” Harris corrected. “Try not to confuse the two. At least not while we’re holding clamps.”

They moved down the rows. Harris greeted his own men by name, checking bandages, cracking jokes. When they reached the German side, he switched to more formal German.

“How’s the leg today, Müller?” he asked a lanky POW with a cast.

“Better, Herr Kapitän,” Müller said, eyes flicking to Ernst with wary curiosity.

“This is Dr. Brandt,” Harris said. “He’ll be helping out around here. Be nice to him. He’s had a rough week.”

There were snickers.

Ernst felt heat rise up his neck.

On the far side of the ward, a voice called out in German, “So this is where our colonels end up. Washing bandages for the enemy.”

Ernst turned.

A group of German officers lounged between beds, cigarettes dangling from fingers, posture too relaxed to be entirely natural. At their center sat Major Otto Reinecke, once of the Waffen-SS, his black uniform replaced by POW gray but his bearing unchanged.

Reinecke’s eyes were sharp, assessing.

“Oberstarzt Brandt,” he said. “I heard you’d been captured. I didn’t expect to see you holding an American’s coat.”

“I am assisting in the hospital,” Ernst said. “Our men are here. Someone must look after them.”

Reinecke’s lip curled.

“Is that what you call it?” he asked. “Looking after them? Under enemy supervision? Do they teach you new ways to stitch, Brandt? Using their hygienic democracy?”

His companions chuckled.

Harris watched the exchange, expression unreadable. He didn’t interrupt. Not yet.

Ernst forced his shoulders to stay level.

“We have wounded,” he said. “They need care. I am a doctor.”

“You are a German officer,” Reinecke said sharply. “Or have you forgotten? Your first oath is not to the man on the table. It is to the nation he served.”

Harris stepped in then, his German crisp.

“Funny,” he said. “Mine is to the patient first. Perhaps that’s why our guys let your colonel here treat them. They know he knows what he’s doing, regardless of which flag was on his sleeve before.”

Reinecke turned his gaze on Harris.

“You should watch which Germans you trust, Captain,” he said. “Some of us remember where we come from.”

“I’d be worried,” Harris said lightly, “if I were asking him to guard anything other than a scalpel. As it is, I’ll take my chances.”

The tension between them sparked, then settled into a low simmer.

“Come on,” Harris murmured to Ernst. “We have a schedule.”

As they walked away, Ernst felt the prickling heat of Reinecke’s stare between his shoulder blades.

In the small scrub room off the main ward, as they washed up for the morning’s first operation, Harris spoke without looking at him.

“He doesn’t like you much,” he said.

“He preferred it when I signed requisitions instead of patient charts,” Ernst replied. “He always thought doctors wasted their loyalty on people instead of the cause.”

“And what do you think?” Harris asked.

The question landed heavier than the soap in Ernst’s hand.

He thought of the directive on the Eastern Front. Priority to those who could return to combat. He thought of the faces he’d watched fade when he’d had to tell a nurse, “No, leave this one. We have orders.”

“I think,” Ernst said slowly, “that medicine without loyalty becomes… hollow. But loyalty without medicine becomes something worse.”

Harris rinsed his hands, turned off the tap with an elbow.

“Good,” he said. “Let’s see if we can find the middle without killing anyone.”

For a while, camp life settled into a strange rhythm.

Ernst assisted in surgeries, mostly on Germans—removing shrapnel, debriding wounds that had been left too long. He helped with rounds, with triage, with the endless paperwork that came with any army.

The Americans let him into their operating theater under guard at first. After a week without incident, the guard started standing outside instead of in the room. After two, he started reading a newspaper during procedures.

“You’re good,” Harris said once, as Ernst tied off a bleeder with quick fingers. “Efficient. Didn’t expect that from a guy who used to outrank everyone.”

“Work doesn’t care about rank,” Ernst said. “Blood is the same height on any sleeve.”

Harris snorted.

“Don’t let Reinecke hear you say that,” he said.

Reinecke and his circle stayed away from the hospital physically, but their presence lingered in the barracks. They held loud discussions about honor and betrayal, about “collaboration,” the word spat like a curse.

One evening, in the dim light of the barrack’s single bulb, the argument came to a head.

“Brandt,” Reinecke said, voice carrying. “We need to talk.”

Ernst had been sitting on his bunk, reading a tattered medical journal someone had smuggled into camp. He folded it carefully and looked up.

Reinecke stood in the aisle, hands behind his back. A small crowd had gathered, sensing a show.

“Yes, Major?” Ernst said.

Reinecke’s jaw worked.

“Word is,” he said, “you helped operate on an American today.”

Ernst shrugged. “He was bleeding,” he said. “It seemed unwise to let him continue.”

Murmurs. Someone hissed under their breath.

Reinecke’s eyes flashed.

“You betray us,” he said. “You betray every German who died under their bombs, every man rotting in their camps.”

Ernst felt something twist inside.

“I also operate on Germans,” he said. “Every day.”

“Under their command,” Reinecke snapped. “Like a dog fetching for a new master.”

“I am a doctor,” Ernst said, hearing the word grow thinner each time he used it as a shield.

“You are what you choose to be,” Reinecke shot back. “I chose my loyalty. Even here. Even now. When they tell you to cut one of theirs instead of one of ours, will you obey? When they tell you to share our medical records with their interrogators, will you hand them over?”

“That has not happened,” Ernst said.

“Yet,” Reinecke said. “They use you because it flatters you. A little respect after they’ve taken your rank. A warm room. Clean instruments. It’s easy to forget who you are when the water is hot and the coffee is theirs.”

Ernst set the journal aside, stood slowly.

“Who am I then, Major?” he asked.

“A German officer,” Reinecke said. “Or have you become just a pair of hands?”

Ernst’s pulse thudded in his throat.

He thought of the plank with Else and Lena’s names. Of the factories that had drawn the bombs. Of the boys on his operating tables, their eyes wide and trusting.

He also thought of the American he’d stitched up that afternoon—some kid from Ohio with a hole through his thigh, muttering about baseball in the recovery room. Harris had bent over him, adjusting the drip.

“You’re going to be fine, Private,” he’d said. “You can complain about the food in no time.”

To Harris, it hadn’t mattered that the bullet had been German. To Ernst, it had felt… clean.

In the barracks, Ernst met Reinecke’s stare.

“I am a man who helped do terrible things,” he said quietly. “Sometimes directly. More often by doing nothing. I signed papers that sent people away. I enforced policies that let some die and saved others based on what uniform they wore.”

Reinecke’s mouth curled. “So now you seek absolution from the enemy?” he sneered.

“No,” Ernst said. “There is no absolution. Only choices about what to do with what remains.”

He took a breath.

“You talk about loyalty,” he said. “Loyalty to what? To the men who told us we were superior? To the symbol that brought bombs down on our own cities? My wife and daughter were killed by those bombs, Major. Doesn’t that earn me the right to decide what my loyalty means now?”

The barracks had gone very still.

Reinecke’s jaw clenched.

“You sound like them,” he said. “Like their pamphlets. Their broadcasts.”

“Perhaps they were right about some things,” Ernst said, surprising himself.

A ripple of shock ran through the room.

Reinecke took a step closer, eyes wild.

“Be careful,” he hissed. “Traitor is a small step from coward. And we still remember what to do with traitors.”

“Enough,” another voice said.

Harris stood in the doorway, a guard behind him. He must have been passing by when the volume rose.

“This is a POW camp, not your old officer’s club,” Harris said. “We’re not going to have show trials in the barracks. You don’t like that Dr. Brandt works in the hospital, take it up with me. But you will not threaten him. Or anyone else.”

Reinecke’s gaze flicked between Harris and Ernst.

“You can protect him here,” he said. “You can’t protect him from what comes after.”

He stalked away, his shadow shrinking with distance.

Harris stepped inside, the guard hovering at the threshold.

“You alright?” he asked Ernst quietly.

Ernst sank back onto his bunk, suddenly exhausted.

“I am discovering,” he said dryly, “that there is more than one way to be a prisoner.”

Harris’s mouth twisted.

“Welcome to the club,” he said.

The shocking truth arrived three weeks later in the form of a convoy.

It rolled into camp on a gray morning, trucks growling, the air heavy with the smell of diesel and something else Ernst couldn’t place at first. Not cordite. Not blood. Something sour, like sick bodies packed too close.

Harris burst into the hospital ward, unshaven, eyes sharper than Ernst had ever seen them.

“Brandt,” he said. “I need you. Now.”

Ernst stripped off his gloves, wiped his hands.

“What has happened?” he asked.

Harris grabbed an extra tray of instruments, gestured for Ernst to follow.

“They’re bringing in prisoners from a camp,” he said. “Our boys liberated it yesterday. It’s… bad.”

“Prisoners?” Ernst repeated. “Our soldiers?”

Harris stopped so abruptly Ernst nearly ran into him.

“No,” Harris said slowly. “Not yours. Theirs. Civilians. Political prisoners. Jews. People your lot locked up and forgot how to feed.”

The words hit like a slap.

“That’s enemy propaganda,” Ernst said reflexively. “Exaggerations. There were—”

Harris cut him off with a look Ernst had never seen in his eyes before. It wasn’t anger. It was something colder.

“I have seen things in the last 24 hours,” Harris said quietly, “that I would not describe even to my worst enemy. And I am not a man prone to exaggeration.”

They stepped out into the yard.

The trucks lined up in a row, canvas flaps open. Medics moved between them, faces set in a kind of numb focus Ernst recognized from the Eastern Front.

Inside the trucks were people.

They were not soldiers. They were not even, in the first glance, distinguishable as men and women. They were shapes under blankets, gray faces peeking out, eyes sunk deep into skulls. Skin clung to bone like damp paper. Some had hair; some did not. Numbers were tattooed on forearms like dates on meat.

The smell hit Ernst full force—a mix of sweat, excrement, infection, and something else that made bile rise in his throat.

He heard, distantly, the sound of retching. One of the younger American medics bent double, vomiting into the mud. Another man clapped his shoulder, then turned back to his work.

“This is one of the better camps, they say,” Harris muttered.

Ernst stared.

His brain, desperate for familiar categories, tried to file what he saw under “refugees,” “displaced persons,” “casualties of advancing fronts.”

It didn’t fit.

These people had not been caught in crossfire. They had been starved. Over time. Deliberately.

He saw ribs like ladder rungs under skin. He saw sores where bone had rubbed through. He saw eyes too old for any face.

A woman clutched a bundle to her chest. Ernst thought it was a baby until he saw the stillness of the limbs and realized it was a body, too small even in her arms.

“Put them in here!” Harris shouted, pointing. “Triage by breathing and pulse. I don’t care what language they speak. I care whether they’re alive in an hour.”

He turned to Ernst.

“You’ve never seen anything like this?” he asked.

Ernst’s mouth was dry.

“I have heard rumors,” he managed. “Stories. Exaggerated. Enemy lies.”

Harris’s jaw tightened.

“Take a good look,” he said. “Tell me if you think anyone alive could invent this.”

An American medic struggled to lift a man whose legs were little more than skin-covered sticks. Ernst stepped forward, instincts kicking in, helping ease the man onto a stretcher. His hands brushed bone.

The man’s eyes fluttered open.

They were blue. Clear. Confused.

He whispered something in a language Ernst didn’t know—Polish, maybe. Or Yiddish.

Ernst’s German words caught in his throat.

He had treated emaciated soldiers before—men pulled from encirclements, retreats. This was different. This was not the result of a failed supply line or a sudden collapse.

This was the result of time. Of decisions. Of systems.

He flashed back to an office in 1940, when a liaison from the SS had visited the hospital. “Certain populations,” the man had said, “are being resettled. Relocated. You need not concern yourselves with them. The Reich will be stronger for it.”

Ernst had nodded, filed the phrase “certain populations” under “politics,” and gone back to his charts.

Now those phrases had bodies.

He helped move patients for hours. He started IVs. He wrapped bone-thin arms in blankets. He listened for breaths so shallow he had to lean close.

Between tasks, his eyes kept catching on those numbers burned into skin.

Eventually, the hospital filled beyond capacity. Beds were dragged into hallways. Americans and Germans worked side by side, passing bandage rolls, holding basins.

At one point, Ernst found himself at a light box, X-ray held up, evaluating the chest of a man who looked more skeleton than human. The transparent ribs arced across the film, casting stark shadows. The heart was an oversized blur—strained, struggling. Spots in the lungs suggested infection.

Harris leaned in beside him.

“See?” he said softly. “He’s about thirty, maybe. Weighed as much as you or me once. Now his heart is trying to pump blood through a body a child’s size. It’s tired. Some of them simply… stop.”

Ernst swallowed.

“Triage?” he asked.

Harris’s mouth twisted.

“We do what we can,” he said. “But some of these cases… if we pour resources into them, they might live another week. Another month. Or they might die tomorrow. Meanwhile, there are others we can actually bring back.”

He hesitated.

“We’re not gods, Brandt,” he said. “We’re men with bandages in a world that’s been bleeding for too long.”

The words echoed something Ernst had thought years before, at the Eastern Front, when resources had been scarce.

But then, the shortages had been the enemy’s fault. The Bolsheviks. The winter. The Führer’s stubbornness. Whoever he’d needed to blame.

Here…

Here, the scarcity had been engineered.

“Who did this?” he whispered, more to himself than to Harris.

Harris heard anyway.

“Men in uniforms,” he said. “Some like yours. Some with different badges. Some in suits who signed papers. Some who just drove trains and decided not to ask where they were going.”

Ernst’s hand shook, the X-ray rattling slightly on the light board.

“These are isolated incidents,” he said weakly. “War is… messy. Some camps. Some abuses. Not…”

He trailed off. The words tasted obscene in his mouth.

Harris looked at him.

“Brandt,” he said quietly. “We found ledgers. Lists. There are more camps. Many more. This wasn’t a mistake. It was policy.”

Ernst closed his eyes.

Policy.

He saw memos now in a different light. “Jews resettled from this district.” “Gypsies removed.” “Political enemies neutralized.”

He had told himself those were security matters. He had signed where necessary.

He had never once asked, “Where exactly are they going?”

The X-ray’s light glowed through his eyelids.

When he opened them again, the image of the frail chest blurred with the memory of another film—his own, a few weeks earlier, shard of shrapnel lodged near his ribs.

Harris had pulled that shard out with care.

No one had pulled anything out of these people. Only taken.

Ernst felt something inside him give way.

He lowered the X-ray slowly.

“I wore the swastika,” he said. The word felt heavier now than any metal badge. “I told myself I was not… one of them. I was a doctor. I patched up soldiers. I did not carry guns into villages. I did not… push people into trains.”

Harris watched his face.

“And now?” he asked.

“Now I see what those trains delivered,” Ernst whispered.

He put his hand over his mouth, as if he could push the shock back in. It didn’t move.

On the other side of the ward, Reinecke stood in the doorway, flanked by a couple of his circle. He’d come, perhaps, to gloat over the Americans’ new burden.

His face was pale.

He caught Ernst’s eye, then looked away quickly.

That night, long after they’d run out of morphine and clean sheets, after three of the camp survivors had died quietly and another had woken screaming and then slipped back into unconsciousness, Ernst sat on a bench outside the hospital.

The air was cold. The stars overhead looked indifferent.

His hands were raw from washing and gloving and ungloving. His back ached. His brain felt like someone had taken a scalpel to it and sliced away its neat compartments.

Harris sat beside him, elbows on knees, cigarette between two fingers. He offered one to Ernst.

“I don’t smoke,” Ernst said automatically.

“You might start tonight,” Harris replied.

Ernst took the cigarette.

The first drag made him cough. The second steadied his hands.

They sat in silence for a while.

Finally, Ernst spoke.

“You knew,” he said. “You Americans. The British. You knew about these camps.”

Harris exhaled smoke.

“We heard stories,” he said. “There were reports. People who escaped. Whisper networks. Some believed them. Some didn’t. Some didn’t want to. It was easier to think it was just… war. The usual ugliness.”

He stared at the glowing tip of the cigarette.

“Seeing it,” he said, “is different.”

Ernst nodded.

“I heard stories too,” he said. “About your bombings. About civilians killed. Women. Children. I told myself… that even if it was brutal, it was… symmetrical. We hit you. You hit us. It’s what war is.”

He looked at his hands.

“I did not imagine… that we were doing this while telling ourselves we were more civilized,” he said.

Harris’s mouth tightened.

“You had help,” he said. “The world let you pretend, for a long time.”

They fell silent again.

“It would be easy,” Ernst said slowly, “to say that I did not know. That I was just a surgeon. That my hands were busy with other things. It would be easy. And false.”

He remembered the liaison officer’s smooth assurances. The vague language. The way he’d avoided asking questions that might make his work harder.

“I chose not to know,” he said. “That is different from ignorance.”

Harris nodded.

“At least you see that,” he said. “Some of your compatriots are already rehearsing different lines.”

He jerked his chin toward the shadows near the barracks, where Reinecke stood with a small knot of men, voices low and harsh.

“They say we staged it,” Harris said. “That we starved those people ourselves to make you look bad. It would be funny if it weren’t so obscene.”

Ernst stared at Reinecke.

“Can you blame them?” he asked quietly. “It is easier to spit ‘lie’ than to swallow what we saw.”

“That doesn’t make it less poisonous,” Harris said.

“Poison takes time to purge,” Ernst replied.

“Think you can help?” Harris asked. “From your side, I mean?”

Ernst laughed, a short, humorless sound.

“Do I look like a man anyone listens to?” he asked.

“You looked like that when you were signing orders too,” Harris said. “They listened then.”

Ernst flinched.

“It is a bitter thing,” he said, “to realize the weight of your signature only when it’s too late.”

He stubbed the cigarette out on the bench.

“What will you do, Brandt?” Harris asked. “After the war. Assuming you don’t end up in one of those courts they keep talking about.”

It was the first time anyone had mentioned trials to his face.

Ernst considered.

“If they call me,” he said slowly, “I will go. I will tell them what I signed. What I chose not to ask about. What I saw. I will not say ‘just following orders.’ It is not enough.”

“And if they don’t?” Harris pressed.

“Then I will go home,” Ernst said. “If there is one. I will stand in whatever ruins are left. And I will tell anyone who will listen what we did.”

He looked at his hands.

“I used to think my job was to keep bodies alive,” he said. “Now I think my job is to keep memory alive. At least, the part that hurts.”

“That’s not much of a retirement plan,” Harris said.

“No,” Ernst agreed. “But it’s better than looking away again.”

He hesitated.

“Your camp,” he said. “You treat us… according to law. You treat these survivors… as if they were your own. You treat me as if my oath still means something. That is… not what we were told about you.”

Harris snorted.

“I’m sure you were told we eat babies and throw priests off cliffs,” he said. “Propaganda is a cheap diet.”

“It was a rich one, at the time,” Ernst said. “Now it tastes like ash.”

He looked at Harris.

“Your shocking truth,” he said. “It is not that my side committed atrocities. Even we suspected that, some nights. It is that you did not. Or at least, not in the same way. That you chose… restraint. Law. Even when you could have chosen revenge.”

Harris raised an eyebrow.

“You give us too much credit,” he said. “We’re not saints. We’ve shot prisoners in the heat of battle. We’ve bombed cities so hard I’m not sure what we were aiming at anymore. We’re not innocent.”

“No,” Ernst agreed. “But you are… bounded. That is the difference.”

He thought of Reinecke’s eyes, gleaming with injured pride.

“I wore a uniform that told me I was above bounds,” he said. “That only our will mattered. I see now where that road leads.”

Harris studied him for a long moment.

“You know,” he said, “some of my colleagues would say I’m crazy to trust you with so much. To let you see our records. Our wounded. To talk like this.”

“Perhaps they are right,” Ernst said.

“Maybe,” Harris said. “Or maybe, if anything decent is going to grow out of this mess, it’ll be because some of us took risks like this. With people like you.”

He stood.

“Get some sleep,” he said. “Tomorrow, the camp survivors will need more of those hands you’ve been trying to hide behind your guilt.”

Ernst smiled faintly.

“I thought guilt was the necessary anesthesia,” he said.

“Only if you let it numb you,” Harris replied.

Years later, when Ernst stood in a lecture hall in a rebuilt German university, gray hair at his temples and a neat suit replacing his uniform, he would tell medical students how he’d learned what the word “oath” really meant.

He would not start with grand statements about ethics. He would start with the Eastern Front. With the directive about prioritizing soldiers. With the liaison from the SS and the vague talk of “resettlement.”

He would describe, in calm words, how easy it had been to slide. How the path from “this is not my department” to “I don’t want to know” to “I refuse to believe” had been paved with small, comfortable decisions.

Then he would tell them about the American camp.

About Captain Michael Harris and his insistence that a patient was a patient, regardless of uniform.

About truckloads of survivors from camps with names etched now in Europe’s memory.

About the X-ray that had shown him a heart struggling in a body his own country had starved.

He would watch the students’ faces—a new generation, eyes wide, some skeptical, some already impatient with stories of an old war.

He would tell them, “You will be asked to compromise. To ignore. To prioritize the useful over the inconvenient. You will tell yourselves you are just doing your job. I did. Learn from my failure.”

He would say, “Medicine does not exist outside politics. But it must not become its servant.”

And, if any of them asked why they had to keep hearing about something that happened before they were born, he would take a breath and answer, “Because I once stood in a clean ward and told myself the filth was somewhere else. It was not. It never is. It starts where we stop looking.”

He would think, sometimes, of Reinecke. He had disappeared into the machinery of postwar justice—trials, sentences. Ernst had read his name once, in a newspaper, then never again.

He would think, often, of Harris.

They had corresponded after the war, letters crossing oceans with stories of hospital politics instead of battlefield triage. They had argued, still, about bombing campaigns, about whose civilians had suffered more, about how tribunals had been conducted.

But beneath it all was a shared conviction: that the line Harris had drawn in that camp hospital—patient first—was one of the few straight lines they could still trust.

In his last years, when his hands shook too much to hold a scalpel, Ernst would sometimes wake in the night, heart pounding, smelling again the sour air of the trucks, seeing again the numbers on skin.

He would sit, breathe, remind himself of later images: bright lecture halls, grandchildren with no memories of sirens, hospitals where patients wore gowns instead of uniforms.

He knew he had not redeemed himself. Some debts were greater than any lifetime could pay.

But he had, at least, stopped pretending he owed more to a flag than to a human being lying on a table.

That, he thought, was the shocking truth he’d found in an American POW camp: not that his enemies were better than he’d been told, not that his country had done worse than he’d wanted to believe, but that the choice between healer and accomplice had always been his, even when he’d tried to pretend otherwise.

He had simply run out of places to hide from it.

THE END

News

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si el capitán estaba desequilibrado… hasta que 36 marinos subieron a cubierta enemiga y, sin munición, pelearon cuerpo a cuerpo armados con tazas de café

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si…

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19 Silent Refugees, and One Impossible Decision Changed the Battle Forever

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19…

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the Reckless Engineer, a Furious Staff Argument and the Longest Span of WW2 Turned a River Into the Allies’ Unbreakable Backbone

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the…

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a 39-Kill Nightmare That Changed Everything in a Single Brutal Month Over Europe

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a…

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their Isolated Ridge, His Fight With the Sergeant, One Jammed Machine Gun and 98 Fallen Enemies Silenced Every Doubter

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their…

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His Metal Legs Locked Onto the Rudder Pedals, He Beat Every Test, and Sent Twenty-One Enemy Fighters Spiraling Down in Flames

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His…

End of content

No more pages to load