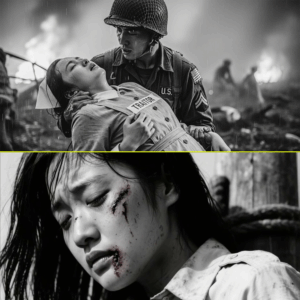

He Thought She Was the Enemy Until He Read the Tag on Her Wrist: How a Nisei Soldier Saved a Japanese POW Nurse Branded “Traitor” and Discovered His Own Courage

By the time Sergeant Kenji “Ken” Nakamura saw the word on her wrist, he’d heard it his whole life.

Traitor.

Not in Japanese, not with ink on skin, but in the quieter ways people looked at his family in California after December 7th. In the barbed wire around the camp in the desert. In the way the recruiting officer raised an eyebrow when he walked into the office and said, “I want to serve.”

Now the word was right in front of him, written in black characters on a filthy strip of linen tied around the wrist of a Japanese nurse sitting alone in the corner of the POW enclosure.

裏切り者.

Uragirimono.

Traitor.

Ken stopped short in the packed red dirt, the humid air hugging his neck like a damp towel. The smells of the processing yard swirled around him—sweat, iodine, boiled coffee from a field kitchen down the slope, and the faint metallic tang that lingered after every battle.

The POW pen was a rectangle of barbed wire and rough posts, slapped together on the leeward side of the ridge. Inside, dozens of Japanese prisoners sat or squatted, some in tattered uniforms, some stripped to undershirts, all of them exhausted, their eyes tracking every move of the American guards on the perimeter.

Most of the prisoners clustered together in knots around battered canteens, around the single water barrel, around the makeshift latrine. But in the far corner, separated by several arm-lengths of tamped dirt, sat one woman in a grimy white nurse’s smock, back straight despite the slumped weariness around her.

Her hair, once probably neat and pinned, now limped out of its bun in greasy strands. She was barefoot. Her knees were drawn up, arms wrapped around them. And around her right wrist, like a crude bracelet, was that strip of cloth, ink bleeding slightly into the weave.

“Sergeant?” called Lieutenant Reynolds from behind him. “You seeing what I’m seeing?”

Ken kept his eyes on the tag. “Depends,” he answered. “Are you seeing a woman with a bandage where her name should be?”

“I’m seeing our only Japanese medical staff POW so far,” Reynolds said, stepping up beside him. “A nurse. And from the way the others have been looking at her, I’m guessing she’s not winning any popularity contests in there.”

Ken had noticed it too. Every time a prisoner went near the corner to drink from the barrel or relieve himself behind the screen, his gaze snagged on the nurse. Some glared. Some spat in the dirt. One had hissed something under his breath—quick, sharp syllables Ken caught without even meaning to.

“Uragirimono.”

Traitor.

Reynolds shifted his helmet back, squinting. “What’s that say?” he asked, nodding toward the linen strip. “Can you read it?”

Ken inhaled slowly, the tropical heat swelling in his lungs.

“It says ‘traitor,’ sir,” he replied.

Reynolds let out a low whistle. “So it wasn’t just my imagination.” He crossed his arms. “Figure out what that’s about, will you? Before someone decides to settle an old score through the fence.”

Ken’s jaw flexed. “Yes, sir.”

Reynolds glanced sideways at him. “You all right with this, Nakamura?”

Ken knew what the lieutenant was really asking: Are you all right talking to people who look like you but would have shot you an hour ago?

He’d been answering that question since he’d joined the Military Intelligence Service.

“Yes, sir,” he said again, and started toward the gate.

The guard at the gate—Corporal Doyle, sunburned and perpetually chewing something—straightened as Ken approached.

“Interpreter coming through,” Ken said. It was half announcement, half warning.

Doyle moved aside and lifted the loop of wire that served as a gate latch. “You want me in with you?” he asked.

“Stay close,” Ken said. “But let me try talking before we add extra rifles to the conversation.”

“You got it, Sarge.”

The instant Ken stepped inside the enclosure, the atmosphere shifted. The prisoners’ murmurs dropped to a low buzz. Dozens of eyes flicked to his face, then to his uniform, then to his face again. You didn’t have to be a mind reader to catch the confusion there.

Japanese features in an American uniform did that to people.

He kept his posture easy, his hands visible, his voice calm.

“Watashi wa Nakamura gun-sō desu,” he said in clear Japanese. I am Sergeant Nakamura. “Amerika-gun no tsuyaku desu.” I’m an interpreter for the U.S. Army.

A ripple went through the group. A few men stiffened. One older soldier barked, “You shame your ancestors!” under his breath.

Ken’s stomach tightened, but he didn’t break stride. He’d heard worse—in English and Japanese.

He walked toward the far corner, where the nurse sat with her knees hugged to her chest, eyes fixed on a patch of dirt between her bare feet.

Up close, she looked younger than he’d thought. Mid-twenties, maybe. Younger than him by a couple of years. Hard to tell under the grime and exhaustion.

“Sumimasen,” he said gently, stopping a few paces away so he wouldn’t loom over her. “May I speak with you?”

Her eyes flicked up, iris dark, sharp even through the haze of fatigue. For the briefest second they brightened in recognition—Japanese face, Japanese eyes—then clouded with suspicion when they took in the olive drab uniform, the U.S. patch, the stripes on his sleeve.

“You’re… Japanese?” she asked in their language. Her voice was hoarse, but steady.

“Japanese American,” he replied. “My parents were born in Japan. I was born in California.” He offered a small, wry half-smile. “So I confuse people. On both sides.”

She stared at him, then let her gaze drop pointedly to his uniform. “You work for them,” she said quietly.

“I work for the United States,” he answered, just as quietly. “It’s my country.”

Her lips pressed together, and for a moment he thought she might spit at his boots. Instead she looked away, jaw clenched.

“You can call me Ken,” he said. “What’s your name?”

She hesitated, as if even offering that was a concession. Then, reluctantly,

“Sato Naomi,” she said. “First name Naomi.”

He nodded. “Naomi-san. May I sit?”

She almost said no. He could see the refusal forming in the tightening of her shoulders. But something—weariness, perhaps, or the uselessness of protest now—made her give the smallest nod.

He lowered himself into a squat a polite distance away, boots flat, elbows resting on his knees, matching her height. The dirt was hot even through the soles.

“Naomi-san,” he said. “I’d like to ask you about… that.” He gestured to her wrist, to the stained band of linen. “Who put it there?”

Her fingers twitched, as if tempted to hide the tag in her sleeve. Then, deliberately, she pulled her hand into her lap, palm up, letting him see the word more clearly.

“The doctor,” she said. “Our own. Before they left.”

“The Japanese doctor?” Ken clarified. “Not our medics.”

A humorless flicker passed through her eyes. “You think you Americans had time to write Kanji on the wrists of your prisoners?” she asked. “No. It was one of ours. He wanted everyone to know what he thought I was.”

“Which is?” Ken prompted.

She looked up, meeting his gaze.

“A traitor,” she said flatly. “To the Empire. To the Army. To them.” Her chin flicked towards the other prisoners. “And maybe… to you as well.”

The word sat heavy between them. Ken felt it in the back of his throat, where old insults and new loyalties had scraped for years.

“What did you do,” he asked quietly, “to earn that many people’s anger?”

Naomi held his gaze for a long moment, as if weighing whether anything she said could possibly matter now.

“Are you asking as my interrogator?” she said. “Or as… something else?”

“As someone who has been called that word too,” he replied.

Her eyes sharpened. “You?” she said. “Your own people call you traitor?”

“My own people?” he repeated. “Which ones? The ones who sent my family to a camp in the desert because of our faces? Or the ones in here who look at me like I’ve betrayed a blood oath?”

He hadn’t planned to say that much. The words surprised even him. Maybe the heat was loosening his tongue. Or maybe it was the way she sat there with that ugly word on her wrist, like they were both walking around with the same invisible sign.

Naomi’s expression changed—just a flicker at the mention of his family in a camp—but she didn’t look away.

“I am a nurse,” she said, voice gaining a little strength. “Or… I was. Army hospital unit. I treated our wounded. I followed orders.” Her fingers curled slightly. “Until the orders were to stop treating certain men. To let them die because they had tried to surrender, or hesitated, or… questioned.”

Her throat worked. Ken stayed quiet.

“I refused,” she continued. “I said a man bleeding on a cot is just a body that needs help, not a lesson. The doctor said I was weak. An enemy of discipline.” Her mouth twisted. “He said if I cared so much about cowards, I could join them.”

“And that’s when you got that?” Ken asked, nodding toward the tag.

She nodded once. “He tied it on himself,” she said. “In front of everyone. Said, ‘Now they will know who you are.’”

Ken exhaled slowly. “And who you are, in your mind?” he asked.

She looked at him, something fierce and fragile behind her eyes.

“I am a nurse,” she repeated. “I was meant to save lives, not choose which ones deserved it.”

Her hand brushed the band on her wrist. “If that makes me a traitor, then I suppose I am one.”

The first time someone called Ken a traitor, he’d been twelve.

He’d been leaving school, backpack slung over one shoulder, when a man had shouted from a truck idling at the curb.

“Go back where you came from!” the man had yelled. “Traitor!”

Ken had stared, stunned, arms full of textbooks about American history and English grammar. He’d been born in Fresno. His favorite baseball team was the San Francisco Seals. He’d known the Pledge of Allegiance before he knew his grandparents’ village names.

That night his mother had held his face in her hands and said, “You know who you are, Kenji. Don’t let someone’s fear rename you.”

He’d tried to hang onto that. Even when the FBI agents came to their house after Pearl Harbor. Even when the notice went up ordering all persons of Japanese ancestry to report for relocation. Even when the train took them to a barren camp surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

“Why are they doing this to us?” his kid sister had asked, eyes huge in the dust.

“Because they’re afraid,” he’d said. “And they’re wrong.”

When the Army later announced that Japanese Americans—even those with family behind wire—could volunteer for service, Ken had gone down to the recruiting office anyway. Some said he was crazy. Some said he was brave. Some whispered traitor under their breath.

“Which is it, Mom?” he’d asked, half joking.

She’d looked at his new uniform, at the flag patch on his shoulder, and said, “Maybe it is its own thing. Maybe it’s just you being you.”

He’d chosen the path that was both complicated and simple: serving the only country he’d ever known as home, using the language his parents had brought with them across the ocean.

Now, sitting in the POW pen across from a woman whose own people had named her traitor for a different kind of refusal, he felt that old tension hum in his bones.

“Naomi-san,” he said carefully, “the men in my unit want to know if you’re dangerous. If this ‘traitor’ label means you’re an informant, or a spy, or… something that could hurt them.”

She laughed, short and sharp.

“Dangerous?” she said. “Look at me.” She held up her hands—calloused, scraped, but empty. “I have no weapons. The last time I tried to hurt someone it was an infected toe that wouldn’t stop bleeding.”

He couldn’t help it; a corner of his mouth quirked.

“Then why are they so angry with you?” he asked, glancing at the other prisoners.

She followed his gaze.

“Because I did not agree to die the way they wanted,” she said. “Or to watch others die for nothing.”

She drew in a breath, her shoulders tightening.

“When the shelling began, the officers told us if the enemy got too close, we were to leave the most wounded behind,” she said. “No morphine, no mercy. Just… let them slow you down.” Her fingers dug into her knees. “I hid ampoules in my pockets. I went back. I gave some men a chance not to be in pain. The doctor caught me. He called me traitor to the end.” Her lips twisted. “He ran. I stayed with the men who couldn’t.”

Her voice went quiet. “That is why I am still here to talk to you.”

Ken’s throat felt thick.

“You disobeyed orders,” he said softly.

“I chose a different duty,” she replied. “It seems every side has words for that.”

For a long moment, the only sounds were the low murmur of the other prisoners, the clink of metal mugs at the water barrel, the distant rumble of trucks down on the road.

Behind Ken, Corporal Doyle shifted his weight. “You getting anything useful, Sarge?” he called, trying to sound casual.

“Yes,” Ken answered, still watching Naomi. “Very useful.”

Lieutenant Reynolds listened to Ken’s report with a frown that deepened the line between his eyebrows.

“So she disobeyed her own officers to help wounded men,” he said slowly. “That’s what got her that label.”

“Yes, sir,” Ken said.

“She didn’t feed any intel to our side. Didn’t sabotage anything. Didn’t, I don’t know, smuggle maps.”

“No, sir.” Ken’s tone stayed even. “If anything, her actions probably kept some of our guys under fire longer. Some of those wounded may have gone back to fighting if she helped them.”

Reynolds snorted. “Great,” he said. “So she’s a traitor and a headache.”

Ken hesitated. “With respect, sir,” he said, “she’s a medic who refused to go along with what she thought was wrong. That’s… not something I want to punish.”

Reynolds studied him for a beat. “You’re not being objective about this, Nakamura?” he asked. “Given your own… experiences?”

There it was again, that careful dance around the fact that Ken’s family was behind barbed wire because a lot of people still didn’t trust faces like his.

“I’m being as objective as a man can be out here, sir,” Ken said quietly. “If she’d been giving us trouble, I’d tell you. She hasn’t. The problem is inside the pen.”

“You think the other prisoners might hurt her?” Reynolds asked.

“I think some already want to,” Ken said. “They’re not stupid enough to start something with our rifles pointed at them. But tempers don’t need much excuse.”

Reynolds drummed his fingers on the edge of the table—just a crate with a map tacked on top.

“What do you suggest?” he asked.

“Move her,” Ken said promptly. “Assign her to our medics’ tent under guard. She’s trained. Doc Harris is begging for extra hands. We gain a nurse, we lower the temperature in the pen, and we stop tacitly agreeing with that label on her wrist.”

Reynolds raised his eyebrows. “That’s a lot of trust to give someone who was patching up men trying to kill us yesterday.”

“She’ll be under supervision,” Ken said. “She can’t exactly run off with our secrets. And if we’re serious about the Geneva rules, sir, we’re supposed to treat medical personnel differently from combat troops.”

Reynolds sighed. “You and your rule book,” he muttered. Then, more loudly, “You really believe she won’t stick a scalpel into somebody’s throat the first chance she gets?”

“I believe,” Ken said slowly, choosing each word, “that a woman who risked being called traitor by her own side to ease suffering isn’t likely to start causing it for ours.”

Reynolds stared at him a moment longer, then let out a breath.

“All right, Sergeant,” he said. “I’ll talk to Harris. We’ll move her under guard, see how it goes. But if this blows up in our faces—”

“It won’t,” Ken said, more confidently than he felt. “I’ll keep an eye on her.”

“You planning on being her shadow now?” Reynolds asked dryly.

“Call it… part of my job as interpreter,” Ken replied.

Reynolds smirked. “You and your big heart,” he muttered. “Dismissed.”

Moving Naomi was supposed to be a simple operation: open the gate, escort her out with two guards, walk her down to the aid station.

It turned into a flashpoint before the first step.

When Doyle unlatched the gate and called Naomi’s name, she stood slowly, hugging her arms around herself.

Several prisoners snapped to attention, hearing the name. The older soldier who’d hissed at Ken earlier took a step forward, eyes narrowed.

“Where are they taking you?” he barked at her in Japanese.

“To the American medical tent,” Naomi said, voice steady enough to surprise herself. “To work.”

The word hung there: work. As in, for the enemy.

The man’s face twisted. “So now it is official,” he snarled. “You don’t even pretend anymore.”

She lifted her chin. “They asked. I agreed,” she said. “I am a nurse. I will treat whoever is bleeding. Even you, if you are brought there.”

A murmur went through the pen, anger and disbelief braided together.

“You shame us,” another man spat. “You shame the Emperor.”

One of the younger soldiers—barely more than a boy, bandage wrapped around his temple—lurched forward, hand half-raised as if to strike her.

Ken stepped between them without thinking.

“Enough,” he said in Japanese, his voice cutting through the rising noise. “You’re prisoners now. She’s a prisoner. None of you get to decide who lives or dies anymore. That job is out of your hands.”

The young soldier glared at him. “And in yours, America-jin?” he sneered, emphasizing the word like a curse. “You think wearing that uniform makes you one of them? You’re just another traitor—hers, not ours.”

The word slid into Ken’s ears with that old sting, but he didn’t flinch.

“I’m a soldier doing his duty,” he said. “Same as you thought you were, once.”

The older soldier spat in the dirt. “We will remember this,” he muttered to Naomi. “When we go home.”

Naomi laughed softly, a sound with no humor in it.

“If we go home,” she said.

Ken touched her elbow—lightly, barely. “Come on,” he said in English. Then, in Japanese, “This way.”

She moved past him, back straight, the linen band on her wrist stark against her skin.

As they walked out of the pen, Ken had the odd sensation of stepping through a line on the ground he couldn’t see—one that separated not just enemies and prisoners, but all the versions of himself that might have been.

Doc Harris was, predictably, unimpressed at first.

“I asked for help, not more complications,” he grumbled when Reynolds and Ken brought Naomi into the aid station tent. “I’ve got wounded Americans in here who don’t exactly feel warm and fuzzy about Japanese uniforms walking past their cots.”

“She’ll stay on the far side,” Reynolds said. “You said yourself you needed someone who knows how to clean a wound without making a mess of it.”

Harris scowled, rubbing the bridge of his nose. “Can she follow instructions?” he asked.

Ken translated. Naomi’s lips twitched.

“I managed not to kill anyone in our ward,” she said dryly. “Despite some of the doctors’ efforts.”

Ken suppressed a smile as he translated. Harris’s eyebrows went up.

“All right, nurse,” the medic said. “You so much as look sideways at a scalpel when my back’s turned, and you’re out, got it? But if you can keep your hands steady and your head on straight, we might just make this work.”

Naomi nodded. “Understood.”

They started her on the basics: washing instruments, changing dressings under supervision, fetching water, checking bandages for seepage. Harris watched her like a hawk at first, arms folded, jaw set.

But competence has a way of wearing through suspicion.

She moved with practiced efficiency—rolling down a bandage, checking the skin beneath for redness, cleaning gently, rewrapping with sure fingers. When a young private flinched as she approached, she stopped a few feet away, met his eyes, and said in halting English, “I help. I not hurt.”

Her accent made the words softer. The private hesitated, then nodded, jaw tight.

As the days passed, her presence became part of the odd rhythm of the station. American groans and Japanese instructions mingled under the canvas. “Hand me that clamp” began to sit alongside “Hairetsu o mite”—check the alignment.

Ken found himself acting as bridge more often than not. He translated Harris’s jokes so the tension would ease. He put Japanese words to American procedures—suture kit, antiseptic, morphine.

One afternoon, as Naomi smeared salve over a rash on a sergeant’s arm, the man squinted at Ken.

“She understand me if I say thanks?” he asked.

Ken translated. Naomi glanced up, startled.

“You’re… welcome,” she said in careful English.

The sergeant managed a brief, stiff smile. “Guess we’re both stuck here, huh?” he muttered.

“Guess so,” she replied.

Ken watched the exchange, feeling something he almost didn’t recognize at first.

Hope.

Not the loud, trumpeting kind. The quiet sort that creeps in when people who were never meant to share air start to share small, necessary kindnesses.

At night, when the aid station quieted—not silent, never that, but less frantic—Naomi would sit on an overturned crate outside the tent, looking up through the gap in the palms at the unfamiliar constellations.

The linen tag was still on her wrist. No one had ordered her to remove it, and she hadn’t asked. It felt less like a sentence now and more like a reminder.

One evening, Ken joined her, easing down beside her with two enamel mugs in hand.

“Coffee,” he said, offering one. “Very American. Very bad.”

She accepted the mug, sniffed cautiously. “It smells like burned beans,” she said.

“That’s because it is,” he said. “Tastes better than it smells. Sometimes.”

She took a tiny sip and grimaced. “This is what they fight for?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “Baseball. We fight for baseball.” When she looked blank, he added, “It’s a game. Long story.”

She absorbed that, then glanced at his profile.

“Tell me about… the camp,” she said, surprising him. “The one your family is in.”

He’d mentioned it once, in passing, when trying to explain why the word on her wrist sat uncomfortably on his skin too. He hadn’t gone into detail.

“What do you want to know?” he asked.

“Everything,” she said. “Nothing. I don’t know.” She turned the cup in her hands. “We were told…” She trailed off.

“Told what?” he prompted.

“That Japanese people in America would rise up,” she said slowly. “That they would sabotage, spy. That the American government would never trust you. That they would… remove you.” Her fingers tightened. “Some said we should be proud of that. That it meant we were feared.”

Ken nodded, not surprised. “Some people did fear us,” he said. “We tried to show them they were wrong. Some listened. Some didn’t.”

He stared into the dark liquid.

“The camp…” He hesitated, then continued. “They called it relocation. Said it was for our safety, and everyone else’s. My parents lost the store they’d run for twenty years. We had to sell what we could carry. They gave us little tags with numbers and put us on trains.”

“Tags,” she said softly, her gaze dropping to her wrist.

He followed her eyes.

“Ours had numbers, not words,” he said. “But sometimes it felt the same.”

“Did anyone call you traitor there?” she asked.

“Not out loud,” he said. “They didn’t have to. The fences said it.”

“Why did you still join their army?” she asked, the question that had burned behind her eyes since the first time she saw him.

He thought about all the half-answers he’d given to others. To recruitment officers. To nosy fellow soldiers. To himself.

“I wanted to prove I belonged,” he said. “To show them I was American. That I wasn’t what they feared.” He shrugged. “And…I wanted to do something that felt like it mattered. Sitting behind wire while other people shaped the world outside didn’t sit right.”

“Even if it meant fighting men who looked like your uncles,” she said.

He flinched inwardly. “Even then.”

She considered that. “You are very… complicated,” she said finally.

He huffed a soft laugh. “You’re one to talk, Naomi-san.”

They sat in silence for a moment.

“Do you hate them?” she asked suddenly.

“Who?” he said.

“The Americans who put your family in the camp,” she said. “The ones who look at you and see… not enough.”

Ken tipped his head back, studying the slice of night sky.

“I used to think hate would keep me warm,” he said. “But it just kept me tired. So now I try to save it for things that deserve it. Like bad coffee.”

She smiled despite herself.

“And you?” he asked. “Do you hate the doctor who gave you that?” He nodded toward the band.

Her hand moved to it unconsciously.

“I did,” she said. “In the moment. When he tied it and said I had betrayed everything. When the others looked at me like a stranger.” She exhaled. “Now…I mostly feel sorry for him. That his world was so small he couldn’t see past his orders.”

Ken nodded slowly.

“Maybe that’s the real difference between traitors and… whatever we are,” he said. “Whether we choose to stay in the small world someone drew for us. Or step outside it.”

She looked at him. “Outside,” she repeated. “Like here.”

“Like here,” he agreed.

They sipped coffee that tasted faintly of seawater and burnt hopes, and for a little while the war felt a fraction of a degree farther away.

The war didn’t end in a single moment for them. It ended in announcements over tinny loudspeakers, in rumors rushing through barracks, in cheers and silence and men staring at their hands as if seeing them for the first time.

For Ken, it ended in a briefing tent where an officer read out the terms of surrender from a typed sheet, his voice oddly flat.

“For you MIS boys,” the officer added, “it means more work. Translation. Processing. Reconstruction. Hope you weren’t planning on a long vacation.”

Ken hadn’t been planning anything beyond the next day. The future had felt too big to look at directly.

For Naomi, it ended in a notice tacked to the POW camp bulletin board—repatriation schedules, lists of ships, instructions for returning personnel.

“Your case is… unique,” a Red Cross worker told her, frowning slightly at the form with her name on it. “Some of your former compatriots have, ah, opinions.”

“They always have,” she said calmly. “The boat doesn’t care.”

Still, there were moments when old labels threatened to leap new fences. A Japanese officer at the camp glared openly when he saw her helping an American nurse change a dressing. A passing comment—“collaborator”—drifted to her ears.

She turned away, focusing on the patient in front of her, the same way she had the night she refused to abandon wounded men.

The day before Naomi was due to be transported to a port for repatriation, Ken found her in the aid station, carefully inventorying supplies they’d be handing over to a new unit.

“You’re leaving,” he said, stating the obvious.

“Yes,” she said. “They say I will see my homeland again soon.” Her fingers paused on a bottle of aspirin. “It feels like trying to remember a dream I woke from too quickly.”

He nodded. “Do you have anyone waiting?” he asked.

“My mother, if she is still alive,” she said. “A younger brother, maybe. Our last letter from him was… before.” She didn’t define before.

“Mine are in California,” he said. “Camp’s closing. They might be back home by the time I get there. Or what’s left of home.”

They stood there, two people suspended between places, between labels.

Naomi glanced at her wrist. The linen strip was frayed at the edges now, the ink faded but legible.

“You know,” she said slowly, “when I go home… that word will follow me. Not written, maybe. But in whispers.”

He met her eyes. “What will you do?” he asked.

She took a breath. “The same thing I did when they tied it on,” she said. “I will be a nurse. I will help rebuild. I will treat whoever comes into my ward. If that makes me traitor to someone’s idea of purity, then I will be that.”

He reached into his pocket. “Then consider this a counter-label,” he said.

He pulled out a narrow strip of olive drab cloth—cut from an old, worn-out uniform—and a stub of pencil. Quickly, he wrote four characters, brow furrowed as he remembered the strokes from childhood lessons at the Japanese school in Fresno.

He handed it to her.

She looked down.

勇気ある者.

“Yuuki aru mono,” she read aloud. “‘One with courage.’”

He shrugged, suddenly self-conscious. “My kanji might be rusty,” he said. “But… seemed more accurate than ‘traitor.’”

Her throat worked.

“They will not let me wear this,” she said. “Not… openly.”

“It’s not for them,” he said. “It’s for you.”

She folded the cloth carefully, then untied the old linen band. Her wrist felt oddly bare without it. She slipped both strips into the small cloth pouch she wore around her neck, next to the photo of her family she’d kept safe through everything.

“Will they call you home now?” she asked him.

“Eventually,” he said. “They still need interpreters. Someone has to sit at tables and argue about rice shipments instead of artillery ranges.”

She imagined him at such a table, translating words about trade and reconstruction instead of surrender terms.

“Do you think they will ever stop calling you… traitor?” she asked.

He thought of the old man in Fresno, of the guard in the camp who had refused to look at him, of the soldier in the POW pen.

“Maybe not all of them,” he said. “But I’ve learned I don’t have to wear every name someone hands me.”

She nodded slowly.

“Then we are the same that way,” she said.

“Yeah,” he replied. “I guess we are.”

They stood there in a silence that wasn’t empty at all.

“Naomi-san,” he said at last, “when you’re in a hospital in Yokohama or Tokyo someday, and some young doctor tells you to let a patient suffer because of politics… what will you do?”

She smiled, small and fierce.

“I will say,” she answered, “‘I am a nurse. My duty is to the living.’ And if they call me traitor again…” She shrugged. “I will think of a Nisei soldier who wrote ‘one with courage’ on a scrap of cloth, and I will remember that someone once agreed with me.”

His chest tightened.

“And you?” she asked. “When someone in your country forgets what you did, forgets where your family sat behind wire… what will you do?”

“I’ll keep showing up,” he said. “Keep speaking up. Keep being both things they say can’t exist together.”

“Japanese and American,” she said.

He nodded. “Nurse and traitor,” he added wryly.

She laughed, the sound surprising them both.

“Maybe someday,” she said slowly, “people will understand that loyalty and conscience are not enemies.”

He looked at her, at the woman who had sat in the dirt with a word around her wrist and chosen, over and over, not to let it define her.

“Maybe someday,” he agreed.

When they said goodbye at the transport truck the next morning, it was without big speeches.

“Take care, Naomi-san,” he said simply.

“Take care, Nakamura-san,” she replied. Then, after a heartbeat, “Take care, Ken.”

He smiled. “You too.”

The truck pulled away in a cloud of dust, carrying her toward the long journey home. He watched until it disappeared around the bend.

Then he turned back toward the camp, toward his work, toward the messy task of helping two countries who had torn each other apart figure out how to live in the same world again.

Years later, long after the camps had closed and new wars had begun in other places, a letter crossed the Pacific in a Red Cross pouch.

It arrived at a modest house in California where an aging former sergeant sat at a kitchen table, reading glasses perched low on his nose.

The envelope was thin, the handwriting on the front careful, the characters a mixture of English and Japanese.

“Mr. Kenji Nakamura,” it read.

He opened it with fingers that weren’t as steady as they’d been on that island.

Inside, on faintly yellowing paper, was a letter written in neat Japanese script.

Dear Nakamura-san, it began. Or should I say, dear Sergeant Ken.

You may not remember me. I was one of many you spoke to, one of many you helped. But I have carried your name, and that piece of cloth, for many years.

He read on, the past rising up around him in waves.

I am writing from a hospital in Yokohama, she wrote. Not as a patient, but as a head nurse. We rebuilt slowly, stone by stone, bed by bed. There were days we treated people whose uniforms I had grown up fearing. There were days we had to decide how to stretch medicine between too many hands.

On those days, when someone questioned why I would treat “the enemy,” I thought of the word the doctor tied on my wrist. And then I thought of the words you wrote to replace it.

He could almost feel the frayed linen between his fingers.

I have been called many names since the war, she continued. Some kind, some not. But the ones that matter most are the ones my patients whisper when they leave the ward on their own two feet.

She didn’t write those words out. She didn’t have to.

I hope life has been kind to you, she wrote. I hope your family’s shop is open again, and that your children—if you have them—grow up in a world where no one looks at them and sees a traitor for the shape of their eyes.

She signed it simply:

With respect,

Sato Naomi

(former Army Nurse, former POW, always a nurse)

Ken sat there for a long time, the letter open on the table, the afternoon light slanting across the words.

On a shelf nearby, in a small wooden box, was a folded strip of olive drab cloth he’d kept as a reminder of who he believed he could be. Next to it, tucked into the corner, was an old camp tag with his family’s number, saved not out of bitterness but as evidence. Proof that the past had happened, and that they’d lived through it.

He put Naomi’s letter in the box with them, closing the lid with a soft click.

When his granddaughter came running in, breathless from a game outside, he scooped her up onto his knee.

“Grandpa, tell me a war story,” she demanded, the way children do when they don’t understand the weight of what they’re asking.

He thought of battles he could describe. Of close calls and narrow escapes. Of fear and noise and smoke.

Instead, he told her about a nurse on an island who sat in the dirt with a word on her wrist and decided, anyway, to save as many lives as she could.

He told her how people on all sides had tried to rename them both.

And he told her how, sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is refuse to answer to a name that shrinks you, and choose instead the one that calls you toward courage.

“Is that true?” she asked, eyes wide.

“Every word,” he said.

“Did you save her?” she asked.

He thought of Naomi in Yokohama, of the patients whose names he’d never know, of the quiet ripples from one decision on a hot afternoon.

“I think,” he said slowly, “we helped save each other.”

Outside, the world went on—cars passing, children shouting, the distant bark of a dog. Inside, an old man and a small girl sat at a table, building a different story of what it meant to be loyal, to be brave, to belong.

THE END

News

He Came Back to the Hospital Early—And Overheard a Conversation That Made Him Realize His Wife Was Endangering His Mother

He Came Back to the Hospital Early—And Overheard a Conversation That Made Him Realize His Wife Was Endangering His Mother…

He Dressed Like a Scrap Dealer to Judge His Daughter’s Fiancé—But One Quiet Choice Exposed the Millionaire’s Real Test

He Dressed Like a Scrap Dealer to Judge His Daughter’s Fiancé—But One Quiet Choice Exposed the Millionaire’s Real Test The…

“Can I Sit Here?” She Asked Softly—And the Single Dad’s Gentle Answer Sparked Tears That Quietly Changed Everyone Watching

“Can I Sit Here?” She Asked Softly—And the Single Dad’s Gentle Answer Sparked Tears That Quietly Changed Everyone Watching The…

They Chuckled at the Weathered Dad in Work Boots—Until He Opened the Envelope, Paid Cash, and Gave His Daughter a Christmas She’d Never Forget

They Chuckled at the Weathered Dad in Work Boots—Until He Opened the Envelope, Paid Cash, and Gave His Daughter a…

“Please… Don’t Take Our Food. My Mom Is Sick,” the Boy Whispered—And the Single-Dad CEO Realized His Next Decision Would Save a Family or Break a City

“Please… Don’t Take Our Food. My Mom Is Sick,” the Boy Whispered—And the Single-Dad CEO Realized His Next Decision Would…

They Strung Her Between Two Cottonwoods at Dusk—Until One Dusty Cowboy Rode In, Spoke Five Cold Words, and Turned the Whole Valley Around

They Strung Her Between Two Cottonwoods at Dusk—Until One Dusty Cowboy Rode In, Spoke Five Cold Words, and Turned the…

End of content

No more pages to load