“He Expected Cold Barbed Wire and Cruelty — But Inside the American POW Camp, a German Prisoner Found Hot Bread, Music on Sundays, and a Question That Would Not Let Him Sleep: ‘If the Enemy Treats Me Like a Human, Who Am I When the Gates Open?’”

The first thing he noticed was the smell of bread.

It drifted on the Texas wind and slipped through the gaps in the truck’s canvas like a rumor. Hans Keller, twenty-two and hollowed out by months of surrendering ground and certainties, lifted his head from his knees. Across the flat, sunstruck landscape, rows of white barracks shimmered like bone. He had pictured cages, dogs, shouting. He had not pictured the smell of bread.

“America,” muttered the sergeant beside him, as if the country were a joke told too loudly. “They’ll make you soft and then they’ll forget you.”

Hans did not answer. He was counting fences. Two: the outer chain-link with its muted rattle, the inner one neat as a tailor’s stitch. Between them, a strip of sand raked clean, footprints already erased by a rake leaning against a post. Watchtowers at the corners: wooden, almost elegant. The guards wore broad-brimmed hats against the sun and looked, to his surprise, bored.

The truck stopped. A young American officer with a clipboard waited at the gate. He had the look of someone who had always been trusted with keys.

“Gentlemen,” he said in careful German, “welcome to Camp Able. You will be registered, deloused, and assigned bunks. You will not be harmed if you follow rules. You will be punished if you do not. Questions?”

A man in the back asked for water. The officer nodded. “At the pump. Cups are there. One line. No pushing.” He smiled—brief, real. “There is enough.”

The word landed strangely in Hans’s ears: enough. It had been years since anything had been enough.

They shuffled through the process that reduces a soldier to a ledger line. Name. Rank. Place of capture. The doctor—an older man with kind hands and a stethoscope polished like a talisman—listened to Hans’s lungs and said, “Dust,” as if diagnosing a weather pattern. A barber ran clippers across his scalp, and the hair fell in small storms. Under the showerhead, hot water pinned the cold out of him, and he closed his eyes until the soap felt like forgiveness.

When he emerged, an orderly handed him a linen bag stamped U.S. ARMY. Inside: two sets of clean clothing with PW stenciled in black, a towel so white it made his fingers look like stains, a bar of hard, fragrant soap, a pair of socks without holes. He had forgotten the feeling of fabric that did not argue with skin.

His assigned barracks smelled of pine and soap and something faintly sweet. Bunks in perfect lines. A potbelly stove. A window raised halfway to let in the kind of breeze that understands it is a guest. On each pillow lay a folded slip of paper: Camp Rules in plain German—no climbing fences, no hoarding food, no fights, no sabotage, attend roll call, work if assigned, respect others. At the bottom, the line that made the men look at each other: Violations will be punished, but dignity will be maintained.

Dignity. A word that had not appeared on orders in a long time.

At noon, a bell rang. They filed into a mess hall where an American cook with forearms like tree trunks handed out metal trays: stew thick with beans and carrots, bread warm enough to steam the skin, coffee that tasted like earth and decision. Hans carried his tray to a table and sat. Across from him, a boy with freckles pushed his bread around and muttered, “Trick.”

“Eat,” said the American who patrolled the aisle. “Please.” He did not carry a rifle. He carried a ladle.

Hans tore the bread. The crust crackled like brittle paper. He put a piece on his tongue and it dissolved into a taste that made him stupid with memory—Mother’s kitchen on Sundays, snow melting in the seams of boots by the stove, the scrape of Father’s chair and the way he always cleared his throat before speaking as if making room for words.

He ate. When he finished, he wanted to weep and did not.

The days found their rhythm quickly, as days do when they are given clean edges. Wake-up at six, roll call, breakfast, work details or classes, lunch, line inspections, recreation, lights-out. The camp was a small, efficient country that had declared war on chaos and boredom. The guards were firm and, to Hans’s shock, fair. They corrected without humiliation. They laughed—not at the prisoners, but at jokes that had nothing to do with them. They asked after coughs, after blisters, after letters from home.

Letters. The Red Cross delivered them by the sack, stamped and opened and resealed. Hans’s first arrived in late April, the paper thin as onion skin and the writing deeply familiar, Mother’s careful hand making each letter an apology. We received your notice. We are relieved you are alive. The barn roof is mended. Your sister’s baby cries like a kettle. The pastor says God’s mercy travels faster than war. At the end, a line that made him reread the whole letter to see if he had misunderstood before: Do not be ashamed if you are fed by those you were told to hate. Hunger is not loyal.

He kept the letter under his mattress like a passport.

The work was varied: some days kitchen duty peeling sacks of potatoes as if they were mistakes to be erased; some days mending fences with pliers and patience, barbs like arguments that needed careful fingers; some days stacking lumber, the smell of resin catching in the throat. In exchange, there were small privileges: extra bread, more time in the library, which was a surprise itself—shelves with dictionaries, volumes of Goethe and Schiller, a stack of American magazines with women smiling in a way no one in Europe had smiled in years.

There were classes, too, if you wanted: English in the afternoons with a schoolteacher from Ohio who said th as if it were a door you could open. Arithmetic with a humorless corporal who loved fractions as if they were his children. Civics, on Saturdays, for those who were curious or skeptical or simply liked to argue. The civics class was taught by a chaplain whose cross shone without scolding. He brought a copy of an American document and laid it on the table like a deck of cards.

“Rights,” he said in German. “Not because of behavior. Because of existence.”

The men scoffed, half out of habit, half out of fear of believing. The chaplain did not flinch. “You don’t have to love us,” he said. “Just read.”

Hans read. The sentences were simple, blunt, almost naive. The words did not swagger. They occupied the page the way decent people occupy rooms: respectfully.

On Sundays, an orchestra formed out of nothing—because a violin had been smuggled in by a man who had not been able to smuggle his wife; because a clarinet had arrived in a care package from a mother who knew her son’s fingers; because someone had made a drum from a barrel, a skin, and audacity. They played Bach, and then they played something American that sounded like trains taking curves. The guards leaned on the doorframes and listened without pretending not to. Once, the cook cried openly and then laughed at himself, wiping his face with a towel that left flour on his cheek. The sight lodged in Hans’s chest like a seed.

June arrived with heat that made the air look like it was thinking. The fields beyond the fence greened into a color he had forgotten existed. The camp commander—Colonel Avery, a man who wore his kindness like an unstarched shirt—announced a harvest detail: local farmers needed hands, and the Army would lend them some, supervised, paid in scrip. The rumor blew through the barracks and knocked over furniture: Outside the fence. The idea felt like stepping onto ice that might hold.

The first morning, guards marched twenty men through the gate to a truck. Hans was among them. The road ran straight between fields where corn counted the days. They turned down a lane lined with pecan trees and stopped at a farm that looked like postcards—white house, red barn, a porch with a swing that made shadow lace on the steps. A woman in a faded dress stood on the porch with her hands on her hips, assessing them as if they were a flock of stray geese. A boy of eight peered from behind her skirt with the fearless eyes of children who have never been told the world is complicated.

“You the prisoners?” the woman asked the lieutenant leading the detail.

“Yes, ma’am.”

She nodded once, weapons inspected and found adequate. “I’m Mrs. Dalton. The field’s ready.” She pointed to rows of beans like orderly sentences. “Pick what’s ripe, don’t trample what’s not. Drink from that pump, not the well. If anyone wanders, tell them the snakes will do my work before the Army can.”

The men grinned despite themselves. Work is work in any language. They set to it. Hans used his hands with the gratitude of a man returned to a language he had learned as a child. The sun pressed its authority upon their shoulders. Sweat made clean tracks through the dust on their faces. At noon, Mrs. Dalton sent out sandwiches—thick as dictionaries, slathered with mustard, edged in lettuce so crisp it spoke when you bit it. The boy hovered nearby, studying Hans’s armband with PW stenciled bold as a declaration.

“What’s that stand for?” the boy asked.

“Prisoner of War,” Hans said in his careful English.

The boy considered this. “You a bad guy?”

Hans hesitated. The answer had been simple once. “I am… a person,” he said.

The boy nodded as if that settled everything, which perhaps it did. “I’m Sam,” he said. “You want to see my dog?”

He returned moments later with a creature that looked as if God had been interrupted halfway through making a spaniel and told to try again. The dog’s tail moved as if it had its own plans. It licked Hans’s hand with forgiveness Hans did not know how to accept.

At day’s end, Mrs. Dalton handed the lieutenant a receipt for the Army. Then she walked down the line of prisoners and pressed something into each palm: a biscuit wrapped in cloth, a peach heavy with sugar, a small, folded square of paper with a drawing her son had made—a dog, a sun, a man with PW on his sleeve and a smile that made Hans wince because it was too kind for a world this complicated.

“Thank you,” she said. “For the work.”

Hans did not know where to put the thank you. He nodded, and for the first time since the truck had brought him to the camp, he allowed himself to look beyond the fences in his mind.

Back in the barracks, some men ranted. “Propaganda,” one said. “They want to wash our brains with biscuits.” Another agreed loudly, because loudness can feel like courage. Quietly, others tucked their peaches into their shirts, pretending to save them for later and then eating them at once, because sweetness will not be scheduled by mistrust.

That night, Hans lay on his bunk and stared at the ceiling where the faint outlines of knots in the wood looked like continents. He recited to himself the phrases he had been given as a child: Honor. Duty. Fatherland. He added the things the chaplain had said: Rights. Persons. Dignity. He added biscuits and peaches and a dog named something he had not caught. The ceiling refused to arrange itself into a map.

In July, the camp announced a soccer match: prisoners versus guards. The absurdity thrilled everyone. The field was chalked within the fence. A net was strung like a promise. The guards fielded a team of men who ran like men who had been told not to lose. The prisoners fielded a team that had an ace—Kurt, a former club striker whose run cut wind into pieces. The whistle blew. For ninety minutes, the war put down its heavy coat and played, sweating and shouting and laughing with its mouth open.

In the second half, the score tied, Kurt flicked the ball past a guard with a lightness that made the fence seem superfluous. He faked left, glanced right, and chipped the keeper. Goal. The prisoners erupted into a roar that sounded dangerously like joy. The guards clapped despite themselves. The colonel shouted, “Good play!” and then, remembering his uniform, added, “No fraternization,” which made everyone laugh because fraternization had already happened and would not be ordered away.

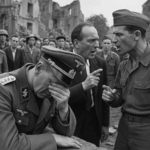

After the match, there were lemonade jugs and paper cups. The cooks, drunk on the idea of occasion, produced a cake decorated with both teams’ names. A photograph was taken: men in shorts and boots, arms slung across shoulders that had been enemies yesterday. In the back row, Hans did not smile; he looked as if a tiny new planet had appeared in his solar system and he was not yet sure of its orbit.

That evening, he wrote to his mother. Today I played against Americans and no one died. They gave us cake with our name on it. I do not understand this country. The chaplain says understanding is not required for decency. I am trying.

Autumn approached and with it rumors, the season’s first crop. The war was ending here, and then there, and then everywhere. The newspapers that trickled into camp wore headlines that were both relief and indictment. The chaplain’s civics class grew more crowded; men wanted to know what would happen to them when the fences became gates. Some were afraid of going home more than they had been afraid of coming here. Some were afraid of both.

One afternoon, the colonel gathered the camp under a sky so blue it felt like it was showing off. He climbed a crate and removed his hat.

“Men,” he began, “news has come that changes everything and nothing.” He paused. “Your country has surrendered.” The word fell with a soft thud. “The war is over.”

No one cheered. A sob, small and feral, escaped someone’s chest and ricocheted through the crowd like a swallowed bird. The colonel’s eyes softened.

“You will not be punished for what you did not do,” he said. “You will be processed and repatriated as efficiently as we can manage. If you fear returning, counselors are available to talk with you. If you do not wish to return immediately, there are formal requests you can file. For now, eat your supper. Tonight there will be music.”

Music. It seemed both appropriate and cruel. That night the orchestra played the slow movement of a symphony that was almost too generous for men with such tangled insides. The guards stood by the doors and watched the music move through the room, rearranging faces like furniture.

After lights-out, a fight broke out near the latrine—a sudden tearing of the peace. Words were said that should not be said in the dark. The guards intervened with discipline and restraint, as if those were two separate tools. The next morning, without fanfare, the colonel assembled the camp again.

“Last night,” he said, “fear wore its boots into our barracks. Fear tells you to be cruel. You have a choice.” He looked at the men as one looks at a class one knows is capable. “Do not let victory or loss make you forget you are men.”

Later, Hans found himself at the fence, staring out across the clean strip toward the second fence, then the road, then the world that might be his again. A shadow fell and resolved into the chaplain.

“Permission to speak?” the chaplain asked, smiling. He always asked as if words were someone else’s property.

“Please,” Hans said.

The chaplain leaned on the post. “You look like a man with two maps.”

“I had one,” Hans said. “Someone has drawn another on top of it.”

“And the roads do not line up.”

“They cross in places. In others they fall off cliffs.”

The chaplain nodded. “Have you learned anything here that does not require you to love us?”

Hans considered. “I learned that coffee can be kind,” he said, surprising himself. “I learned that a man in a guard tower can wave to a child and it does not make him less a guard. I learned that rules written simply might be harder to obey because they are not dressed in fear.”

“And you?” the chaplain said gently. “What did you learn about you?”

Hans looked at his hands—callused, cut, healed. “That I can be grateful without being disloyal. That I can lose a war and gain a different kind of self. That dignity is not something someone gives you. It is something you carry, and sometimes you need a stranger to remind you where you put it.”

The chaplain grinned, unexpected and boyish. “Write that down. It will read well when you forget.”

The days between announcement and transport crawled and sprinted by turns. There were more farm details, more classes, a final soccer match that dissolved into hugs that pretended to be accidental. The orchestra played a last concert, ending with a song the chaplain taught them that had only three chords and a chorus everyone could sing in any language: We will meet again, we don’t know where, we don’t know when. The guards blinked hard and blamed the dust.

On the final morning, Hans packed his bag: one extra shirt, socks, a bar of soap, the book of poems he had checked out and been allowed to keep, his mother’s letter worn fancy by folding, and the drawing from Sam of a dog with a tail like joy. He stood in the doorway of the barracks and looked back once. It looked like order. He felt a sudden, treacherous longing for the safety of a fence that had not demeaned him.

At the gate, Colonel Avery shook each man’s hand as if checking a grip for a lesson learned.

“Mr. Keller,” he said when Hans came forward. He had never called him that before. “A few of the local farmers asked if you might write, when you can. Mrs. Dalton in particular.”

Hans swallowed. “Please tell her—tell them—I will.”

“I have a note from her,” the colonel said, producing an envelope that smelled faintly of biscuits. Hans tucked it with the reverence of a sacrament.

The chaplain stood nearby, his cross warm in the morning. “Remember,” he said softly, “decency is portable.”

On the truck, the sergeant who had warned Hans on that first day climbed up and grunted as he sat. He looked older, as if the months had added rings to him like a tree.

“Soft?” Hans asked, unable not to.

The sergeant stared at the camp. “No,” he said finally. “Just… reminded.” He spat over the side and then, embarrassed by his own poetry, added, “Don’t tell anyone I said that.”

The truck rolled. The fence retreated without triumph. The road unspooled like thread waiting for mending. They passed the pecan lane, and Hans saw a boy running full tilt alongside for a dozen meters, waving, the dog galloping in a cloud of joy behind him. Hans raised his hand and waved back. The boy shouted something Hans could not hear and did not need to.

The convoy headed toward the rail line, toward ships, toward home or what would pass for it after so much had been revised. Hans looked down at his hands and then at the land, which did not know who had planted it and did not care as long as hands were careful.

He closed his eyes and whispered a line he would later put in a letter to his mother, a letter that would weave together fences and biscuits, music and maps, fear and dignity.

They treated me like a man, and now I must learn to deserve it.

News

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the Ashes of a Broken Nation, and Spent Three Decades Rebuilding Trust, Bridges, and the Dream of a United Europe

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the…

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose From the Dust to Prove Skill, Honor, and Command Presence Matter More Than Intimidation or Muscle

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose…

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders, and Quietly Shifted the Balance of a War Few Understood Was Already Changing

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders,…

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a Force Far Stronger and Sparked One of the Most Astonishing Moments of Bravery in Naval History

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a…

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable Trial That Exposed the Fragility of Power and the Hidden Strength of Ordinary People During the Hamburg Crisis

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable…

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into the Pivotal Moment Changing an Entire War at the Battle of Midway

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into…

End of content

No more pages to load