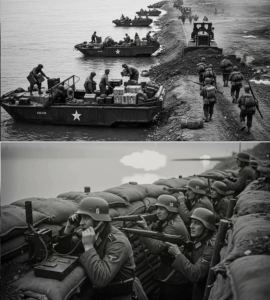

German River Defenses Crumbled When Amphibious ‘Duck’ Trucks Turned the Impassable Rhine into a Highway, and Inside One Secret Crossing an Angry Argument over Risk, Cowardice and Logistics Nearly Sank the Plan

By the time Captain Jack Mercer saw the Rhine, he’d spent three years of his life trying to get things across water.

Pontoon bridges in North Africa. Ferry sites in Italy. Makeshift crossings over rivers in France that had looked small on the map and turned out to be anything but when you were standing on the bank in the rain, watching the current carry logs and the occasional dead cow downstream.

He’d watched too many operations slow to a crawl because supplies couldn’t keep up. Tanks that arrived with their fuel a day late. Infantry who reached an objective only to find their artillery still on the far bank. Men who died in fields that would have been empty if someone had thought to load one more crate of ammunition.

So when he stepped out of his jeep that gray March morning in 1945 and stared at the wide, cold sweep of the Rhine, he felt both very small and very tired.

The river was swollen with spring melt, the surface a restless sheet of gray under a low, sullen sky. On the far bank, the bare trees of Germany stood like a broken picket fence. Somewhere beyond them, enemy guns were quiet for now—but only because the Allied guns on Jack’s side had been thundering all night.

“Big,” said Sergeant Lou Franklin, climbing out of the passenger seat. “Always figured ‘Rhine’ would be more poetical. This looks like the Mississippi got mad.”

Jack grunted.

“Maps don’t remember to mention temperature,” he said. “Or current speed.”

He squinted at the water, watching how it curled around a half-submerged tree stump near the shore.

“Fast,” he added.

Behind them, the staging area bustled. Trucks growled, men shouted, artillery rolled up to pre-sighted positions. A pontoon company unrolled canvas boats and tested their outboard motors, each cough of an engine another small question: will you work when we need you?

A colonel from higher headquarters had briefed Jack’s group the night before.

“Montgomery’s already got his bridge at Wesel,” he’d said, stabbing a finger at the map. “We’re going over here. Ninth Army. XVI Corps. The engineers build bridges, the infantry goes first in boats, then the armor. Your job, Mercer, is to make sure that once we get a foothold, we don’t lose it because nobody remembered to send over gasoline and shells.”

He’d tapped another stack of papers then, as if remembering an afterthought.

“Oh, and those amphibious jobbies you’ve been experimenting with,” he’d added. “The ducks.”

“The DUKWs, sir,” Jack had said. “General Motors 6×6 amphibious truck.”

The colonel had waved a hand.

“Ducks,” he said. “Use them. Don’t use them. Just don’t let my bridges get clogged with your crates.”

Jack had bitten back a retort. If he’d learned anything in three years, it was that logistics officers only got noticed when something went wrong.

He’d also learned that it was the “jobbies” and improvisations—the weird vehicles, the improvised ramps, the decisions made at 0300 in rain ponchos—that won or lost the days after the big arrows on the map.

Now, as he stood on the bank and watched the engineers test the current with weighted lines, he thought about the ducks.

They sat in their own makeshift motor pool behind the tree line: long, low, homely-looking things with boat-shaped hulls and truck tops, painted olive drab. The DUKW had been designed as an all-terrain amphibious truck, capable of driving on land and floating in water, its six wheels retractable, its propeller and rudder controlled from the cab.

To most of the infantry, it was just another piece of weird American hardware. To Jack, it was an answer: a way to move not only men, but supplies, straight from the far bank onto roads without waiting for bridge all-clear.

If he could get permission to use them properly.

“Mercer!”

The shout came from behind him. Major Alan Bowers, one of the senior engineers, strode down the track, helmet pushed back on his head, a rolled-up set of bridge plans under his arm.

“Got a minute to talk about insanity?” Bowers asked.

“Which kind?” Jack replied.

“The floating kind,” Bowers said. “I just came from Corps. They want us to keep the ducks on a short leash.”

“Of course they do,” Jack said. “God forbid logistics should get creative.”

Bowers shook his head.

“It’s not just that,” he said. “They’re worried about interference with the bridging. We’re putting up a Bailey and a heavy pontoon span as fast as we can once the far bank is secured. They don’t want your duck circus clogging the approaches or getting in the way of the anchoring.”

“They want to make sure the big, photogenic bridges go up on schedule,” Jack said. “Which is fine. As long as the first wave doesn’t run out of bullets while the photographers are lining up their shots.”

Bowers grimaced. He liked maps and math more than headlines.

“Oberst thinks the river’s too fast for those things anyway,” he said. “Says you’re going to send them out and lose half of them downstream before they ever reach the shore.”

“Oberst isn’t the one who’s going to be yelling for shells at midnight,” Jack said. “Look, we’ve been in eight-foot seas with those ducks. We’ve landed on beaches under fire. The Rhine is no picnic, but it’s not the Atlantic.”

“Try telling that to the staff,” Bowers muttered. “They see ‘truck’ and ‘boat’ in the same sentence and think ‘toy.’”

Jack took a slow breath.

“Alright,” he said. “Let’s go argue.”

On the German side of the river, Oberleutnant Karl Steiner watched the American preparations through the lenses of a pair of binoculars that had once belonged to a Prussian cavalry officer and now were older than some of the men in his platoon.

The glass was slightly fogged at the edges. So, he thought, were his superiors.

He lay on his stomach in a shallow slit trench near a ruined farmhouse, the remnants of a company—his company—spread out in foxholes and cellars along a stretch of the eastern bank.

Behind them, the village of Rheindorf smoldered in places. Allied bombers had hit it hard the week before, cracking cobblestones and shattering windows in houses that had stood since before Napoleon.

Beyond the village, the remains of what had been a “reserves strongpoint” were now just jagged concrete and a small forest of wooden crosses.

He lowered the glasses, rubbed his eyes.

Down by the river, the Americans moved with maddening calm. Trucks brought in bundles of pontoon bridge sections and stacked them neatly. Men in engineer helmets paced out distances, marking spots with white flags. Others dug gun pits, rolled up barbed wire, set up command tents with large antennas.

“They look like they’re building a festival,” muttered Unteroffizier Max Vogel next to him. “All that bustle. This bank will be full of sausage and beer in no time.”

Karl snorted once, humorless.

“If they bring sausages, I might consider defecting,” he said. “For now, they bring artillery.”

He lifted the glasses again.

Something caught his eye.

Not a tank. Not an ordinary truck.

Down the bank a hundred meters from the main engineer cluster, half hidden behind a stand of trees, sat a row of vehicles that looked like boats that had decided to grow wheels.

Their hulls were rounded, their bows pointed, but above the waterline, they had truck cabins with windshields and canvas tops. A few men in American uniforms moved around them, checking tires, coiling ropes.

“What in God’s name…” Karl murmured.

Vogel squinted.

“Boats… with wheels?” he said. “Perhaps they couldn’t decide.”

Karl adjusted the focus.

He saw one of the vehicles’ drivers climb into the cab, start the engine. The thing chugged forward, rolling down a crude ramp toward the waterline as if it were just a regular truck heading toward a flooded street.

Then, without stopping, it rolled into the Rhine.

Karl tensed, expecting a splash and a sinking.

The vehicle dipped, bobbed, and… floated.

Its wheels churned below the surface for a moment, then retracted. A small propeller kicked in at the rear, spitting water. The “truck-boat” nosed out into the current and turned upstream with surprising stability.

Vogel’s jaw dropped.

“They’re… driving in the river,” he said.

Karl watched, fascinated despite himself, as the strange amphibious vehicle journeyed along the bank for a few hundred meters, then swung back toward shore, its bow cutting the surface like a shallow draft launch. It drove straight up onto the muddy opposite bank, wheels extending again as if nothing odd had happened, and rolled toward a group of waiting soldiers, who greeted it with casual shouts.

“It’s a test,” Karl said. “They’re experimenting. Reconnaissance for ferry sites.”

“Ferry,” Vogel said. “With that? It can carry, what, a squad? Two?”

“Or crates,” Karl said quietly. “Or fuel. Or shells.”

Vogel spat.

“The river is too strong,” he said. “They will capsize if they try to load them. The current will take them. God is not on the side of such… contraptions.”

Karl thought of the past year. The sound of Allied Jabos—the fighter-bombers—screaming down on retreating columns. The endless fuel problems. The bridges blown and repaired and blown again.

He was not sure God was paying close attention to contraptions.

“The staff back at Corps would probably agree with you,” he said. “They think technology has to look impressive to be dangerous.”

“They have their tanks and their planes,” Vogel said. “What more can they need?”

Karl watched another amphibian roll down the ramp and into the water, joining the first.

“What they need,” he said, “is to get those tanks and planes across this river before we can knock them out. Those… ducks, or whatever they are, might help.”

“Ducks,” Vogel said skeptically. “We will shoot them like hunting.”

“Perhaps,” Karl said. “If we have bullets left.”

He lowered the binoculars, heart heavier than before.

He knew that somewhere behind him, far from the front, men in staff cars and intact uniforms still spoke of “impenetrable river lines” and “natural barriers.” The Rhine had been the last line in many speeches. Now he watched the enemy test ways to treat it as an inconvenience.

He thought of writing a report, warning of the amphibious trucks. Then he pictured the staff officer’s face as he read the description and imagined the smirk.

We have bigger problems than toy boats, Oberleutnant.

He folded the glasses.

“Keep watching,” he told Vogel. “And tell the men to dig deeper. The Americans are building something. Our job is to make sure they pay attention to the obvious and forget the quiet parts.”

“That sounds… philosophical,” Vogel said.

“It sounds like the only prayer left,” Karl replied.

In the U.S. Ninth Army’s forward command tent, the argument over the ducks reached a boil.

Jack stood at the end of a long table covered in maps, his hands braced on the edge. Across from him, Colonel McKenzie—chief engineer for the corps—tapped a pencil against the river line, his jaw set.

“For the last time, Mercer,” McKenzie said, “I don’t care how seaworthy your duck-mobiles are. We will not have them interfering with the bridge approaches. We have a schedule. The infantry goes at oh-two-hundred. The first pontoon sections go in as soon as we’ve got a secure strip on the far bank. The Bailey anchors follow. Then the armor. That’s the plan.”

Jack kept his voice level.

“And who supplies the infantry until the bridge can take traffic?” he asked. “We’re not building a heavy span in ten minutes, sir. Even if everything goes right, we’re looking at hours before trucks can cross. They’re going to need ammunition, food, water, medical supplies.”

“We can bring some over in assault boats,” McKenzie said.

“Boats that have to be manned by engineers and infantry,” Jack countered. “Boats that can be shot full of holes. The ducks can come in behind the first waves, using the same smoke cover. They can carry two and a half tons of cargo each—as much as a regular deuce-and-a-half—straight from our depots to the far bank without waiting for the first plank to be nailed.”

McKenzie frowned.

“And what happens when one of them gets swamped?” he demanded. “What happens when the current flips it and a dozen men drown? That will be on my report.”

Jack swallowed his frustration.

“They’re not perfect,” he said. “No vehicle is. But we’ve tested them. In heavy surf, in storms. The Rhine is dangerous, but not beyond what they can handle. We’ll pick our routes. Use guides. We’re not talking about a stampede in the dark.”

At the far end of the table, Major Bowers cleared his throat.

“Sir,” he said to McKenzie, “Mercer’s got a point. The more we can keep heavy loads off the early bridgework, the less stress we put on the pontoons. The ducks could alleviate some strain while we’re still securing the site.”

McKenzie shot him a look.

“Don’t you start,” he said. “You engineers fall in love with anything that floats.”

Bowers spread his hands.

“I fall in love with things that work, sir,” he said. “I’ve seen those DUKWs on the Channel coast. They’re ugly, but they get the job done.”

“I’ve seen them tip over in calm harbor water, too,” McKenzie retorted. “Because some idiot overloaded them or forgot to batten down. The Rhine is not ‘calm harbor water.’ It’s a major river in flood, with debris, currents, and, oh yes, people shooting at us.”

The tent felt smaller, the air heavier.

Jack knew the colonel wasn’t wrong about the risks. He’d been on a duck that had nearly broached in Italian surf when the driver misjudged a wave and their cargo shifted dangerously. They’d been one bad bounce away from turning turtle.

But he also knew what happened when the infantry outran their supply.

He took a breath.

“Sir,” he said, “with respect, this is bigger than whether you have to write an unpleasant paragraph in your after-action report. If those first battalions on the far side run dry because we played safe on the near side, that’s on all of us. The ducks aren’t a sideshow. They’re a way to treat the river as less of a wall and more of a… rough road.”

McKenzie bristled.

“And what happens,” he demanded, voice tightening, “when one of your ducks gets hit in midstream and burns like a Roman candle, and the Germans use it as a target buoy? What happens when your men panic the crossing because they see a truck on fire in the water and think every craft is going to blow?”

Jack’s hands clenched.

“You think I haven’t thought about that?” he said, sharper than he intended. “You think I don’t wake up at night picturing men screaming in a river because I put them there?”

Bowers raised a placating hand.

“Gentlemen,” he said. “This is getting us nowhere.”

McKenzie turned on him.

“This is getting a lot of someones killed if we’re careless,” he snapped.

“And doing nothing also kills people,” Jack shot back. “It just does it later, when nobody traces it back to this conversation.”

The tent went very quiet.

That was a line you had to be careful with—a suggestion that inaction could be as deadly as a direct order. It brushed close to the idea that caution itself might be cowardice.

McKenzie’s cheeks flushed.

“Are you calling me a coward, Captain?” he asked, each word brittle.

Jack felt the bottom drop out of his stomach.

“No, sir,” he said quickly. “I’m calling this situation what it is: damned if we do, damned if we don’t. I’m asking you to let us choose our damned with a clear eye.”

McKenzie stared at him for a long, tense moment.

Bowers shifted, ready to intervene if the colonel decided to make an example of the uppity captain.

At last, McKenzie exhaled through his nose.

“You really believe in these things, don’t you?” he said, voice losing some of its heat.

“I believe in not losing another platoon because the bullets are still on the far bank,” Jack said.

McKenzie rubbed his forehead.

“Fine,” he said. “We’ll compromise. You can run ducks in limited numbers in the first hours—priority to ammunition and medical supplies. No joyrides. No stacking them four deep on the approaches. You coordinate with Bowers so you’re not interfering with bridge assembly. And if I see one of your contraptions blocking a pontoon panel, I will personally ensure you spend the rest of the war inventorying rope.”

Jack felt sudden, immense relief.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “That’s all I ask.”

“Don’t thank me yet,” McKenzie said. “Thank me if we’re all still alive in a week.”

As Jack left the tent, Bowers fell into step beside him.

“You weren’t wrong,” Bowers said. “But you almost danced on the edge there.”

Jack nodded grimly.

“If we’re careful, the ducks will look like genius,” he said. “If we’re not, they’ll look like folly. Either way, the river doesn’t care.”

“Rivers rarely do,” Bowers agreed.

In the early hours of March 24, under a sky lit intermittently by artillery flashes and the ghostly glow of flares, the Rhine assault began.

Kenji’s platoon on the German bank crouched in their foxholes, cold fingers on triggers, listening to the distant thrum of engines building on the far side.

“They’ll come at night,” Vogel whispered. “They always do.”

“They’ll come whenever suits their timetable,” Karl said. “Our job is to be here when they do.”

Signals came from higher command by field telephone—short, clipped orders from unseen officers further back.

“Hold your fire until boats are midstream.”

“Prioritize engineer craft.”

“Muzzle flashes must be limited. Ammunition must be conserved.”

Karl relayed them quietly, his voice carrying down the line.

In between, he heard other voices: messengers breathless with news from other sectors, rumors of bridges intact upstream and blown downstream, reports of artillery units without shells.

They had been ordered to defend this stretch of river, but no one had told them for how long. Or to what end.

“Maybe we’ll stop them,” Vogel said. “Maybe they’ll decide it’s too costly and turn back.”

Karl didn’t answer.

He’d seen the Allied armies grind forward for months. They didn’t seem to know how to stop.

Across the river, Jack stood in the shadow of the tree line beside the ramp where the ducks waited.

The night smelled of cordite, gasoline, and river.

A row of assault boats—low, shallow craft loaded with infantry—bobbed at the water’s edge, engines idling quietly. Engineers checked lines, tightened straps, murmured last-minute advice nobody would remember once the first shot was fired.

Jack’s ducks sat behind them, engines off for now, loaded with neatly stacked crates.

The nearest one, Duck 17, held ammunition: boxes of .30 and .50 caliber rounds, mortar shells, rifle grenades.

Duck 19 carried medical supplies: bandages, plasma, morphine.

Duck 21 had fuel cans and radio batteries.

Their drivers—a mix of seasoned truckers and men who had never been on water before the war—stood by their fronts, helmets strapped tight, life jackets snug.

Sergeant Lou Franklin checked the straps on 17, then looked at Jack.

“You sure about this, Captain?” he asked quietly.

“No,” Jack said. “I’m sure it’s necessary.”

Lou chuckled.

“You and your necessity,” he said. “One of these days, we should schedule a vacation from it.”

A whistle blew. Officers shouted.

“First wave!” someone yelled. “Move out!”

The infantry in the assault boats clambered aboard, weapons clutched, eyes dark hollows under their helmet rims. The outboard motors snarled to life, the crafts nudging into the water, forming a ragged line.

“Hold it steady!” an engineer called.

On the German bank, Karl saw the dark shapes begin to move.

“Boats,” Vogel said, voice tight. “There. And there.”

Karl raised his whistle.

“Remember,” he said. “Engineer boats first. They’re the ones with the big loads. Infantry’s bad, but bridges are worse.”

“Bridges are their problem,” muttered someone down the line.

“Not if they get across,” Karl replied.

He waited until the boats were past the midstream mark.

“Fire!” he shouted.

The night exploded.

Machine guns chattered. Mortars coughed. Tracer bullets stitched across the water, their greenish lines striking sparks as they hit metal and wood.

In the assault boats, men hunkered down, some firing back blindly, others simply holding on and praying.

Some boats reached the far bank, scraping onto the mud under bursts of covering fire. Men spilled out, throwing themselves flat, then scrambling up the slope.

Others didn’t.

From his position, Jack saw two boats in the middle of the river take direct hits. One burst into flame, briefly lighting up the scene like a photograph. The other broke in half, its occupants thrown into the cold water, arms thrashing.

He swallowed hard.

“You want us in?” Lou asked, voice taut.

“Not yet,” Jack said. “We wait for the signal. They’ve got enough targets out there.”

On the German side, Karl watched the first Americans gain the eastern shore.

“They’re fast,” Vogel said.

“So are we,” Karl replied. “Or we used to be.”

He directed machine gun fire at the emerging shapes, rattling the slopes with bullets, but the enemy had picked their landing zones carefully. They used dips in the terrain, small rises—anything to avoid presenting silhouettes.

Flares popped overhead, bathing the scene in a ghostly light. Smoke shells hissed, laying down curtains of white.

Back on the western bank, a runner sprinted up to Jack.

“Mercer!” he shouted. “Colonel says go! Ducks to follow second wave. Priorities as planned.”

Jack nodded.

“Lou!” he barked. “Mount up! Ducks 17, 19, 21—into the water as soon as there’s a lane. Stay behind the assault boats. Use the smoke.”

The DUKW drivers clambered into their cabs, engines coughing into life. Jack hopped into the passenger seat of 17, pounding the dash.

“Let’s take a drive,” he said.

Lou grinned.

“Into hell,” he said.

“Better than hanging around the lobby,” Jack replied.

The first ducks rolled down the ramp.

The sensation of a DUKW leaving land and entering water was always unnerving. The front dipped, the hull shuddered, then, if all went well, the wheels lifted just enough and the buoyancy of the hull took over.

Duck 17 bobbed, settled, then floated.

“Prop engaged,” Lou said, hand on the lever. “Steering to port.”

The engine note changed as the propeller bit into the river. The duck nosed into the current, following the path the assault boats had taken, using their wakes as rough guides.

“Keep an eye on that far bank,” Jack said, scanning through the windshield barely cracked open, the cold night air knifing in.

Tracer fire still stitched the water ahead, but much of it was now aimed at the infantry clusters around the first footholds.

As they reached midstream, the current tugged harder, trying to push them downriver. Lou compensated with careful steering, the rudder biting at the water’s pressure.

Behind them, Duck 19 followed, its driver white-knuckled but steady. Further back, others lined up, waiting their turn.

On the German bank, Vogel blinked.

“What is that?” he said. “More boats?”

Karl lifted the binoculars, squinted.

In the smoky haze, the shapes were hard to distinguish. They were lower in the water than assault boats, longer. For a moment, he thought they were barges—but then he saw wheels.

“Those are the trucks,” he said slowly. “The ones we saw in the test. They’re… actually doing it.”

“What are they carrying?” Vogel asked.

“Whatever they think they need most,” Karl said. “Which means, for us, the worst possible gifts.”

He shouted down the line.

“New targets!” he called. “Aim for the long ones. The ones with the heavy wakes. They will feed this attack.”

Machine gunners adjusted their aim.

Jack heard the bullets hitting the water around them, the plunk and hiss of near misses.

“Zigzag,” he told Lou. “Not too tight. We don’t want to roll.”

Lou grunted, hands firm on the wheel, making small adjustments.

On the far bank, infantry crouched in shell holes, watching the low shapes approach.

“Christ,” said one private. “They’re driving trucks on the water.”

“Just be glad they’re ours,” his sergeant replied.

Duck 17’s bow scraped the mud, hull tilting forward as the wheels found purchase.

“Drive!” Jack yelled.

Lou gunned the engine. The ducks’ tires dug into the bank, pulling the heavy load up and out of the water. The transition was always the most vulnerable moment—neither fully afloat nor fully grounded.

A shell burst nearby, spraying dirt and shrapnel. A fragment pinged off the side of the duck’s hull.

“Welcome to Germany,” Lou muttered.

They lurched forward, climbing the short rise until the ground leveled out.

Ahead, a cluster of American troops huddled behind a low farmhouse foundation.

“Ammo?” Jack shouted.

“God, yes,” their lieutenant replied.

Duck 17 slid in behind the partial cover, brakes squealing.

Jack jumped down, motioning for the men to grab boxes.

“This is for the fifty-cal,” he called. “This crate here—mortar rounds. Don’t mix them up or you’ll have a surprise party.”

The lieutenant laughed despite the danger, hefting a box.

Behind Duck 17, 19 crawled up the bank, medics already waving it toward a makeshift casualty collection point.

Back on the western bank, McKenzie watched through his own field glasses.

He saw the ducks roll into the water, saw them buffeted by the current, saw them emerge on the far side.

He exhaled slowly.

“Looks like your lunatic idea didn’t drown them,” he said to no one in particular.

Bowers, standing nearby, allowed himself a small smile.

“Genius and lunacy are close cousins, sir,” he said. “Sometimes we get lucky which one shows up.”

McKenzie lowered the glasses.

“All right,” he said. “Get more ducks into the water. Ammunition first. Then fuel. Keep the bridge approaches clear, but use them. Mercer was right about one thing—if those boys run dry while I’m still driving decking bolts, I’ll have more than rope inventory to worry about.”

The battle for the bridgehead lasted days.

From Karl’s foxhole, it felt like an eternity measured in artillery barrages and the steady, relentless arrival of more Americans on his side of the river.

They came in boats. They came, more and more, in ducks.

“We shoot them,” Vogel said, weary, “and more come.”

“That is their way,” Karl replied.

He found himself watching the amphibious trucks with a strange mix of hatred and respect. They were not glorious war machines like tanks or fighter planes. No one would paint murals of them. They were plain, pragmatic, and terribly effective.

At one point, he watched one take a direct hit from a mortar near midstream.

For a moment, it looked like a scene from one of the staff’s nightmares: the duck listing, smoke pouring from its hull.

But instead of flipping and sinking, it wobbled, corrected, and limped toward the far bank, the driver clearly fighting the wheel.

Men in the back threw cargo overboard—crates, cans—lightening the load. When it finally scraped the shore, listing, infantry rushed to help pull it up.

“They get hit and keep going,” Vogel said.

Karl frowned.

“Not always,” he said. “We’ve sunk some. Don’t let a survivor erase that.”

Vogel sighed.

“It’s just… they treat this river like a puddle,” he said. “We were told it would stop them. It slows them. That’s all.”

Karl thought of all the speeches he’d heard about “natural barriers.” About “no step backward.”

He thought of those amphibious trucks, those ducks, humbly turning water into something manageable.

“Sometimes,” he said quietly, “a puddle is all you need if you have the right shoes.”

Vogel gave him a sidelong look.

“You’re getting poetic, Herr Oberleutnant,” he said. “War is bad for your cynicism.”

Karl chuckled once, dry.

“On the contrary,” he said. “It confirms it.”

When the Rhine crossings were finally secure, when the bridges arched over the water like steel-backed colossi and armor rolled east in endless columns, Jack stood again on the western bank.

He was exhausted. He hadn’t slept more than an hour at a stretch in three days. He looked like someone who had lost a fight with a coal scuttle.

But when he watched a duck roll out of the river, mud dripping from its hull, driver grinning in relief, he felt something like pride.

Lou climbed down from the cab, stretching his cramped legs.

“That river,” Lou said. “I don’t ever want to see it again.”

“You and me both,” Jack said.

Lou squinted back across the water.

“We did it, huh?” he said. “Rio Grande would’ve made a better story. ‘From Texas to Berlin by duck.’”

Jack laughed, then sobered.

“We did something,” he said. “The rest is up to other people with bigger guns.”

Behind them, a staff car pulled up, engine purring. Colonel McKenzie stepped out, boots crunching on gravel.

He looked older than he had a week ago. Everyone did.

“Mercer,” he called.

Jack straightened instinctively.

“Yes, sir?”

McKenzie glanced at the ducks, at the river, at the occupied far bank.

“I owe you an apology,” he said.

Jack blinked.

“Sir?”

“I let my fear of things going wrong make me hesitate to let something go right,” McKenzie said. “You were right about the ducks. They made a difference.”

Jack shook his head.

“I was stubborn,” he said. “We all were. It worked out.”

“It worked out because you pushed,” McKenzie said. “There’s going to be a lot of talk about this crossing. Bridges, coordination, air cover. But somewhere, in a paragraph nobody reads, it’ll mention that some captain insisted on bringing his weird amphibious trucks along.”

He held out a hand.

“Good work,” he said.

Jack took it.

“Thank you, sir,” he said.

McKenzie nodded toward the far bank.

“The Germans never saw it coming, you know,” he said. “We can hear it on the prisoners’ interrogations already. They expected boats and bridges. They didn’t expect their river to turn into a logistics lane in the first twenty-four hours.”

Jack exhaled.

“You think it ended things faster?” he asked quietly. “This river crossing?”

McKenzie considered.

“Hard to say,” he said. “But I know this much: every day we shaved off this campaign is a day fewer that planes are bombing cities. A day fewer that men are dying in trenches. If a few ugly trucks helped with that, I’m not going to complain.”

He climbed back into his car.

“Get some sleep, Mercer,” he said. “Knowing you, you’re already thinking about the next river.”

Jack watched the car drive off.

Lou whistled softly.

“That was almost… human,” he said. “From the colonel.”

Jack smiled.

“Rivers change people,” he said.

“War does, too,” Lou replied.

On the other side of Europe, years later, Oberleutnant Karl Steiner would sit in a de-Nazification hearing in a small, cold room, answering questions about his time on the Rhine.

He would be asked about his orders, his men, his actions. He would speak of foxholes and bunkers, of artillery and surrender, of the day he laid down his weapon when the ammunition ran out and his company shrank to a handful of hungry, exhausted boys.

The Allied officer interviewing him, a Frenchman with a thin moustache and a stack of forms, would ask, “When did you know the war was lost?”

Karl would think.

“At the Rhine,” he would say. “When I saw them treat that river like… an inconvenience. When I watched trucks float where we had been told only bridges mattered.”

The officer would arch an eyebrow.

“Trucks?” he would ask.

“Boats,” Karl would correct. “Both. Neither. Ugly things that ignored the rules. We had planned around the river. They planned around how to make it irrelevant.”

The officer would scribble something.

“You respect that,” he would say.

Karl would nod.

“I respect the way they thought,” he said. “Not the way they fought, necessarily. War is war. But the thinking… we were taught that will and bravery could make up for anything. They were busy inventing machines that made our bravery bleed faster.”

He’d pause, then add, “If we had spent half as much effort on making sure our soldiers had shoes and food as we spent on flags and speeches, perhaps I would not have watched American ducks bobbing past while my men rationed bullets.”

The officer would give him a long look.

“And what do you do with that respect now?” he would ask.

Karl would shrug.

“I teach my children,” he would say. “That technology is not just toys. That logistics wins wars. That rivers are not promises. And that anyone who says, ‘There is no way the enemy can cross here,’ is either a fool or a liar.”

In a lecture decades after the war, when Jack Mercer, retired colonel, stood in front of a class of young officers, he didn’t talk first about courage or bayonets or heroism.

He talked about ducks.

He showed a photograph of a DUKW rolling out of the Rhine, mud dripping, driver grinning, crates stacked in the back.

“This,” he said, tapping the projected image, “is what caught the enemy off guard as much as any thunder run. Not because it was glamorous, but because it took something they thought was fixed and treated it like a puzzle.”

He told them about the argument in the tent. About how close the ducks had come to staying on the bank. About his own fear that he would send men to drown.

“Our job,” he said, “was not to make the river disappear. It was to make it manageable. To turn a barrier into a workload.”

He saw skepticism in some faces.

“You might never command ducks,” he said. “New war, new toys. But you will meet your own ‘Rhines’—things everyone around you assumes cannot be crossed, or can only be crossed one way. Your civilians will tell you some problems are impossible. Your superiors will tell you some risks are unacceptable. Your job is to be honest about what happens if you don’t try.”

A hand went up in the back.

“Sir,” a cadet asked, “how do you know when you’re being bold and when you’re being reckless?”

Jack smiled, tired and rueful.

“You don’t,” he said. “Not always. That’s why we argue. That’s why we listen to the colonels who are afraid of us drowning. That’s why we look at the river and listen to the men who’ve almost died in one before. Then we decide anyway, and we live—or don’t—with the results.”

He paused.

“But I’ll tell you this: if the only reason you’re not trying something is because you’re afraid of looking foolish in a report, you’re probably leaning toward cowardice, not caution.”

The room was very quiet.

Jack clicked to the next slide.

On it was a map of Europe, the Rhine a thin blue line.

He traced it with a finger.

“The enemy thought this line meant something permanent,” he said. “We turned it into a chapter heading. A paragraph. A crossing. The ducks didn’t win the war alone. Nothing does. But they helped us treat geography as an engineering problem instead of a prophecy.”

He looked at the faces in front of him.

“And that,” he said, “in war and in life, is a very useful habit.”

He ended the lecture there.

Outside, the world went on, full of new rivers, new problems, new contraptions that people would call toys until they crossed something nobody expected.

Back in Europe, the Rhine flowed on, indifferent, carrying barges and tourists instead of ducks.

On some of its banks, small plaques mentioned the crossings of 1945. Most visitors took a photo and moved on.

The men who had been there remembered other things—the shock of seeing a truck float, the fear of stepping into a river at night, the bitter realization that “natural barriers” had a way of dissolving when someone showed up with a strange-looking vehicle and a stubborn logician behind it.

Somewhere, in a basement where an old amphibious truck still sat on display, its hull rusting gently, a child looked up at it and laughed.

“It’s ugly,” she said.

Her grandfather, who had once driven something like it across a river under fire, laughed too.

“Yes,” he said. “But it did a beautiful thing once.”

THE END

News

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si el capitán estaba desequilibrado… hasta que 36 marinos subieron a cubierta enemiga y, sin munición, pelearon cuerpo a cuerpo armados con tazas de café

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si…

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19 Silent Refugees, and One Impossible Decision Changed the Battle Forever

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19…

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the Reckless Engineer, a Furious Staff Argument and the Longest Span of WW2 Turned a River Into the Allies’ Unbreakable Backbone

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the…

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a 39-Kill Nightmare That Changed Everything in a Single Brutal Month Over Europe

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a…

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their Isolated Ridge, His Fight With the Sergeant, One Jammed Machine Gun and 98 Fallen Enemies Silenced Every Doubter

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their…

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His Metal Legs Locked Onto the Rudder Pedals, He Beat Every Test, and Sent Twenty-One Enemy Fighters Spiraling Down in Flames

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His…

End of content

No more pages to load