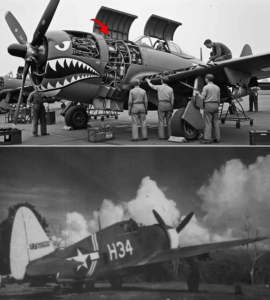

German aces mocked the clumsy “useless” P-47 Thunderbolt as a slow flying bathtub that would never survive over the Reich — until one battered Jug and its stubborn pilot quietly shattered every insult by downing thirty-nine fighters in the space of just thirty days

The first time Lieutenant Jack Murphy heard a German pilot laugh at the P-47, it was over a crackling radio, in a language he barely understood but a tone that needed no translation.

He was sitting in the ready room at RAF Hawkinge, boots up on a battered chair, staring at the blackboard covered in mission times and targets. Rain hammered the tin roof. Someone had tuned the radio to a captured Luftwaffe frequency their intelligence guys liked to monitor for gossip.

“…diese amerikanische fliegende Badewanne…” the German voice said, followed by an easy, confident chuckle. The room’s interpreter, a lanky sergeant from Chicago whose parents were from Hamburg, smirked.

“He said ‘flying bathtub,’” the sergeant translated. “Talking about the P-47s. Says they’re big, slow, useless beyond the coast. Easy meat.”

There was more laughter, joined by another voice. Someone mentioned “Mustangs” with a different respect, and the room went quieter.

Captain Mark Caldwell, a P-51 pilot passing through from another group, grinned and nudged Jack with his boot.

“Hear that, Murph?” Caldwell said. “Even the Germans know the Jug’s a bathtub. You boys should be grateful we brought real fighters to this war.”

A couple of the other Thunderbolt pilots chuckled uneasily. Jack didn’t. He stared at the dust on the floorboards, jaw tight.

“I’ll remember that next time you lot are bingo fuel over Berlin and need someone with a real gas tank to get you home,” Jack said.

It was meant as a joke, but there was an edge to it. The tension, already hanging in the air like cigarette smoke, thickened.

Caldwell leaned forward, suddenly serious. “Come on, Jack. You know I’m right. They’re already talking about phasing your big radials out for more Mustangs. High, fast, nimble— that’s what keeps bombers alive.”

A murmur passed through the Jug pilots in the room. Everyone had heard the rumors. Some pretended not to care. Others, like Jack, felt a cold fist close around their stomach.

“The only reason you can chase anything that far inland is because we spent a year getting shot up teaching the Luftwaffe how hard it is to knock down this ‘bathtub,’” Jack replied. “You ever tried bringing a Mustang home with half a wing missing?”

Across the room, Lieutenant Danny Krause, Jack’s usual wingman, exhaled sharply.

“Easy, guys,” Danny said. “We’re on the same side, remember?”

But Caldwell wasn’t letting it go. He stood, walked over, and tapped the silhouette poster of a P-47 on the far wall— barrel fuselage, stubby wings, big prop.

“Be honest,” Caldwell said. “When you’re up there at twenty-five thousand, dragging that much iron through thin air, you feel it. Takes you half a century to climb. You dive, sure, you’re a brick. But dogfighting Focke-Wulfs? Messerschmitts? This thing’s a pig.”

Conversation in the room slowed, then stopped. The argument was no longer friendly banter; it had become serious and tense, like a thunderstorm gathering above a flat field. A couple of heads turned toward them, eyes narrowing.

Jack stood, boots thudding on the wooden floor.

“You know what we call it?” he asked quietly. “We call it the Jug. And you know why we still love it? Because when you bring a Jug home, it forgives you for every stupid thing you did that day. It takes hits that would tear your pretty Mustang in half and keeps running. It dives faster than anything in the sky. And when those eight .50s speak, things in front of us stop flying.”

Caldwell opened his mouth to answer, but the briefing room door banged open. Major Harlan Pierce, their squadron CO, stepped inside, wearing his flight jacket and that permanently annoyed look he seemed born with.

“Save the aircraft theology for the bar, ladies,” Pierce snapped. “We’ve got a frag order. Target’s Brunswick. Heavy fighter opposition expected.”

The room snapped upright. Chairs scraped. Cigarettes were stubbed out. Caldwell gave Jack a last half-smile.

“Try not to let any bathtubs crack,” the Mustang pilot said, and headed out.

Jack watched him go, anger simmering under his ribs, alongside something uglier: doubt.

Because the truth was, under all that bravado, he’d had the same thought more than once climbing through cloud, watching the fuel gauges tick down: Are we really the right tool for this job?

The Germans on the radio laughed at them. The new darling P-51 pilots mocked them. Even some of their own bomber boys wrote home about “that bulky, ugly American fighter” trying to escort them.

But every morning, Jack still walked out across the wet grass toward the big-radial brute that wore his name under the canopy rail: “Mary Jane II”, a beat-up P-47D with patched bullet holes and a nose art girl who’d survived more than most pilots. Serial number 42-74819. The crew chief swore the airplane had a soul.

If it did, Jack thought, it was a stubborn one.

The sky over Germany was a dirty, layered gray that day, the kind that made altitudes tricky to judge and exhaust smoke hang in bands.

“Blue Leader, this is Blue Two. You still got me?” Danny’s voice crackled in his headset as their flight of four P-47s climbed to join the stream of bombers.

“Loud and clear,” Jack replied. “Form on my right. Keep your head on swivel. Intelligence says they’re desperate enough to throw everything they’ve got at us.”

The B-17s they were shepherding looked like slow, steady islands in a sea of cold air— silver forts, contrails streaming, bombs tucked tight. Somewhere up there ahead and above, other groups had sleek new P-51s flitting around like dragonflies. Somebody had to watch the sides and rear. That was where the Jugs lived.

“Thunderbolts, ugly but faithful,” Danny quipped. “Like that one dog your uncle has that won’t die and scares off every stranger.”

Jack smiled despite himself. “I’ll tell Mary Jane you said that. She’s sensitive.”

They leveled off at twenty-three thousand. The engine hummed, a deep, reassuring vibration through the stick. Jack scanned the sky: above for sun glints, below for dark specks rising, ahead for anything breaking through the contrails.

Five minutes later, the radio erupted with warnings.

“Bandits! Twelve o’clock high, diving on lead group!”

“Someone just called tally-ho on the Mustangs,” Danny muttered.

“Let them dance,” Jack said. “We’ll watch the bombers.”

But the Luftwaffe didn’t read their script.

“Blue Leader, this is Top Cover command. We’ve got reports of a second wave forming at three o’clock low, coming up under the bomber stream. Looks like 190s. That’s your sector.”

Jack’s focus sharpened like a lens turning.

“Blue flight, go line abreast,” he ordered. “Drop tanks. Arm guns. We’re going hunting.”

The empty tanks tumbled away, flashing silver as they fell. His finger flicked the gun switch up; the comforting red “ARM” light glowed.

There: nine, maybe ten dark crosses below, climbing in a loose formation. Focke-Wulf 190s, chunky fighters with butcher-bird reputations. They hadn’t spotted him yet.

Jack nudged the nose forward, feeling the Jug tip over the top of its climb.

“Coming left, twenty degrees,” he said. “We’ll roll in from above and behind. Don’t shoot until you see them fill the glass. You miss, you don’t get a second chance at this altitude.”

“You sure you don’t want to call the Mustangs?” Danny asked.

“Let’s show them what a flying bathtub can do,” Jack said.

Gravity grabbed the P-47 with eager hands. The airspeed needle climbed: 350, 380, 410. The Jug loved to dive. Wind howled around the canopy. The whole airframe seemed to hunch down and grin.

The Germans grew fast in his windscreen now. They were focused on the bombers’ bellies, not on the thin sliver of sky above them where four Thunderbolts streaked down, sun at their backs.

At five hundred yards, Jack picked one 190— the second in their left element, slightly out of line. He led it just a hair, squeezed the trigger.

The Jug shuddered as eight .50-caliber machine guns poured fire. A river of tracers reached out, stabbed into the German fighter’s wing root and fuselage. Pieces flew. Flames licked. The 190 snapped over and tumbled, spinning, a trail of smoke dragging behind it as it fell through cloud.

“One!” Danny yelled. “Nice hit, Blue Leader!”

“Break right!” Jack shouted. No sense flying straight down their lane any longer. The sky exploded around them as the other 190s scattered, some turning toward the P-47s, others rushing the bombers.

For the next ten minutes, the air over Brunswick was a blur of arcs and flashes. Jack fired in short bursts, energy, always energy. Don’t try to turn with them. Climb, dive, roll, use the Jug’s weight like a hammer.

He saw a 190 slide onto Danny’s tail, dove, fired, watched the German pilot jink away— then caught him half a second later when he misjudged the Thunderbolt’s dive speed. Another burst. Another spiraling black cross.

Two.

He took a hit in return— three holes stitched across his left wing, one round pinging off the armor plate behind his head. The Jug shrugged like a heavyweight boxer taking a jab.

Breathing hard, Jack swung around, checked his six, then climbed back toward the bombers.

“Blue Two, you still with me?”

“Still ugly, still flying,” Danny replied. “I’ve got one kill, maybe two damaged. You?”

“Two confirmed,” Jack said. “Maybe a third. We’ll see what the gun camera says.”

By the time they regrouped, the worst of the attack was over. The bombers had taken hits, trailing smoke, a few lagging behind, but the formation held.

Back at Hawkinge that afternoon, their intelligence officer pinned up the mission board results. Under “Claims,” next to JACK MURPHY – LT. – P-47D “MARY JANE II,” he chalked:

FW-190 x 3 (2 confirmed, 1 probable)

“Not bad for a bathtub,” Danny said, bumping his shoulder.

Caldwell, leaning against the wall waiting for his own debrief, glanced at the board, then at Jack.

“Come see me when your flying refrigerator can make it all the way to Berlin and back,” the Mustang pilot said, but there was less bite in it now.

“If the brass ever let us try, we’d probably scare the entire Luftwaffe into quitting,” Jack said.

He said it lightly, but that night, lying in his bunk, he stared at the wooden slats above and thought of three spiraling 190s and the voices on the German radio. Flying bathtub. Useless. Easy meat.

Mary Jane II had come back with holes in her skin and oil streaks down the cowl, but she’d come back. And under her name on the kill board, chalk dust spread into little clouds around three tally marks.

It was only the beginning.

By the time July rolled around, Jack and Mary Jane II had become a running joke and a quiet legend at the same time.

The joke part came from allied propaganda and the Mustang crowd. Newspapers loved the sleek lines of the P-51, the “Cadillac of the sky.” The Jug, in comparison, looked like a barrel with wings.

The legend part came from the scoreboard.

On the blackboard in the squadron ops hut, under “Kills This Month,” someone had drawn a doodle of a cartoon P-47 squashing little black crosses beneath its tires. Beneath it were chalk marks. A lot of chalk marks.

“Thirty-one,” Danny said one evening, counting them off. “You know that, right? Thirty-one in the last three weeks. That’s insane, Jack.”

“Not all mine,” Jack protested. “Some of those belong to you. And to Charlie. And the new kid, Samuels.”

“Sure,” Danny said. “But look closer.”

Next to each mark was a tiny label: M, K, C, S. The majority had an M.

Mary Jane II, flown mostly by Jack, had racked up twenty-seven confirmed kills in the last twenty-one days. A mix of 190s, 109s, and the odd twin-engine fighter. Four more “probables” were waiting on gun camera review.

Part of it was luck. Part of it was that the Luftwaffe was being forced to commit more and more fighters against the ever-growing tide of bombers. And part of it, Jack grudgingly admitted to himself, was that he and his crew were learning how to squeeze every ounce of strength from a machine that had been underestimated.

High cover, low cover, diving slashes, coordinated attacks— they were treating the Jug less like a brute that happened to carry eight guns, and more like a specialist tool.

The German pilots, according to the latest intercepted chatter, had stopped laughing.

“…die Thunderbolts im Sturzflug… vermeiden, mit ihnen nach unten zu gehen…” the radio squawked one day.

The interpreter nodded. “They’re telling each other not to follow the P-47s in a dive. Saying our big fighters are too fast downhill, too tough to knock down. Now they’re calling you ‘Sturzbomber-Jäger’— dive bomber hunters.”

“‘Flying bathtub’ doesn’t sound so funny anymore, huh?” Danny said.

Jack smiled, but there was hardness in it. He’d seen what it took to earn a change in enemy vocabulary: dead men on both sides, smoke against gray clouds, parachutes that didn’t open.

Still, when Pierce called him into his tent one damp morning, he didn’t expect the number the CO slid across the map table.

“Thirty-nine,” Pierce said, tapping the paper. “You and your Jug have racked up thirty-nine confirmed victories this month. Thirty. Nine.”

Jack blinked. “That can’t be right.”

“It’s right,” Pierce said. “Intel double-checked the gun camera footage with bomber reports and radio logs. Some of those kills were after you’d already taken hits that would’ve sent other birds home. That crate of yours—” he jerked a thumb toward the flight line “—shouldn’t even be standing on its gear, let alone flying.”

The report in Jack’s hand listed dates and types in dry typing:

7 JUL – 2 x FW-190

8 JUL – 1 x Me-109, 1 x FW-190

10 JUL – 3 x Me-109

…and on it went.

“I don’t know whether to pin a medal on you or ground you for being crazy,” Pierce said. “Probably both.”

Jack swallowed. Thirty-nine. The number felt unreal, like something out of a comic book.

“Sir, I was just doing my job,” he said.

“You were doing more than that,” Pierce said. “Which is why Group wants to send a photographer over to take your picture for some stateside magazine. ‘Thunderbolt Pilot Defies Odds,’ that sort of thing.”

Jack grimaced. “I’d rather you just give the crew chief more spare parts.”

Pierce snorted. “You and that airplane. You realize you’re proving every fool who called the Jug ‘useless’ dead wrong, don’t you?”

Jack thought of the German radio laughter, of Caldwell’s smirk in the ready room weeks ago.

“I’m proving the Jug’s only useless if you don’t know how to use it,” he said.

Pierce nodded. “Exactly.”

He sobered.

“There’s one more thing,” Pierce said. “INTEL’s picked up talk of a new German formation tactic. They’re sending experienced Rotte— pairs— of their best aces to hunt our top scorers. They’re not just hitting bombers blindly anymore. They’re reading our kill boards, same as we read theirs.”

Jack raised his eyebrows. “You saying I’ve got a target on my back now, sir?”

“You and your bathtub,” Pierce said. “They know the serial number. They know your callsign. One of their Gruppenkommandeure supposedly made a speech: ‘The American Jug that has shamed our fighters for a month will be brought down.’ Their words, not mine.”

Jack let out a slow breath. “Well. That sounds personal.”

“It is,” Pierce said. “Which means tomorrow, you don’t get to make mistakes. Neither does your wingman. I want you at your absolute sharpest. Take tonight off. No booze, no late-night poker. Get some sleep for once.”

Jack nodded and turned to go, the number thirty-nine buzzing around his thoughts like a persistent fly.

“Murphy,” Pierce called after him.

Jack paused at the tent flap.

“Sir?”

“You remember that argument with Caldwell at the beginning of the month?” Pierce asked. “The one I walked in on halfway through?”

Jack shrugged. “Yes, sir.”

“Word is, his buddies aren’t laughing anymore either,” Pierce said. “Couple days ago, one of his boys took flak over Munich and limped home on one engine. A Jug picked up his tail and rode shotgun all the way to the Channel, chasing off two 109s in the bargain. You know what the Mustang driver said when he got out of his crate?”

Jack shook his head.

“He said, ‘That flying bathtub saved my life.’”

They came for him on a bright morning that looked, for all the world, like it had been painted for a propaganda poster.

The air over northern France was a flawless, hard blue. Sunlight flashed off aluminum wings. Down below, patchwork fields slid past like an old quilt.

“Blue flight, check in,” Jack said, scanning his instruments as they climbed.

“Blue Two, looking good,” Danny replied. “If I were any more ready, I’d be bored.”

“Blue Three, no problems,” said Samuels. “Except your singing on the radio, sir. That’s a war crime.”

“Blue Four, still ugly,” Charlie added.

Their target was deep today— the marshalling yards near Kassel. Intelligence said the Luftwaffe had scraped together what fuel they could to mount one of their last big responses. There were rumors of fresh units, replacement pilots, even a couple of experimental aircraft. But what worried Jack wasn’t the unknown. It was the known.

Someone out there, under a black cross, wanted his Jug on the ground.

They reached altitude. The bomber stream stretched ahead and behind them, contrails like scars across the sky. Far above, tiny sparkles marked where Mustangs and Spitfires roamed. Closer in, P-38s flickered like twin-boom dragonflies.

“Blue flight, take four o’clock high,” Jack said. “Stack it up. Eyes everywhere.”

For a while, it was almost peaceful. The rhythmic thrum of the engine, the occasional scratch of the oxygen mask, Danny humming some big band tune over the intercom.

Then: “Bandits! Six o’clock low on the bombers! Looks like 109s—no, 190s too!”

A call from another fighter group. Closer than Jack liked.

“Blue flight, follow me,” Jack said. “We’re going down.”

They started their familiar dance: roll, dive, pick targets, blast, climb. A 190 loomed in his sights; he fired, saw pieces fly. A 109 streaked past his nose, so close he saw the pilot’s scarf whip. He pulled, rolled, felt the G-forces clamp down on his chest.

Two kills, maybe three, in the first chaotic minutes. It would have been another day at the office— if not for what happened next.

“Blue Leader, check your high twelve!” Danny yelled.

Jack yanked his head up just in time to see them.

Two silhouettes, cleaner, darker, more disciplined than the swirling mess of fighters around them. They came in from above and into the sun, classic trap. Whoever was flying them knew exactly what they were doing.

Messerschmitt 109s, but not the worn, patched birds they’d been seeing lately. These looked fresh, sleek. Their movements were crisp, no wasted motion.

“Break right!” Jack snapped, shoving the stick. Mary Jane II rolled heavily, wings biting air.

Tracers stitched through the place he’d been half a second before.

The two 109s split— one went high, zooming up into the sun, the other stayed on his tail, sliding just beyond the reach of Jack’s guns.

“Blue Two, get him off me!” Jack said.

“I’m trying!” Danny grunted. “He’s good—”

The German behind Jack dabbed his triggers. Rounds smacked into the Jug’s right wing with a metallic thud. A gauge glass shattered. Oil sprayed across part of the windscreen.

“Murph, you’re hit!” Danny said.

“I noticed!”

Jack shoved the throttle forward, let the Jug start to do what it did best: fall like a safe.

The airspeed needle leaped. The 109 stayed with him— for a moment. Then, as the Jug sank into the dive, the German fighter began to edge back, unable or unwilling to match the plummeting weight.

Jack grinned, feral.

“Not so easy to chase a bathtub downhill, is it?” he muttered.

At the last possible moment before his stomach tried to leave through the top of his head, he eased back, feeling the Gs crush him, the straps bite into his shoulders. The Jug groaned but held together. Below, a thin layer of cloud streaked past like white smoke.

He broke out under the bombers, leveled for a second, then climbed in a shallow arc, looking for his bandit.

The 109 had pulled out higher, not as deep. Lugging its sleeker frame back up, it crossed in front of him, just for an instant, at maybe six hundred yards.

Jack didn’t hesitate. He squeezed the trigger, let off a one-second burst.

Tracers crawled up and met the German fighter just as it started to roll. The 109’s canopy exploded outward. Flames licked along the fuselage. The pilot bailed out, chute snapping open, a small, frail flower against the deep blue.

“One,” Jack panted. “Who’s his friend?”

As if in answer, the second 109 swooped down from above, cutting across Jack’s nose in a high-speed pass. He caught a flash of markings on the tail— some kind of personal emblem, a stylized bird of prey. This one was aggressive, confident.

“Murphy,” Danny said, breathing hard. “This guy is not like the others. He’s calling the shots. I think he’s the one they sent for you.”

Jack believed it.

“All right,” he said, settling the Jug into a climbing turn. “Let’s make him work for it.”

The next five minutes were some of the purest, hardest flying Jack had ever done.

The German ace—because that’s what he had to be, Jack realized— refused to commit the usual mistakes. He never followed the P-47 too deep in a dive. He tried to lure Jack into flat turns, where the Jug’s weight was a liability, then switched to vertical maneuvers at just the right moments to keep his energy. He took snap shots, not long bursts, preserving ammunition.

Jack matched him move for move, but it was costing him. Sweat crawled down his back. His wounded right wing felt sluggish. The engine temps climbed.

Once, they crossed so close canopy-to-canopy that Jack saw the man’s face clearly: middle-aged, jaw tight, eyes like chips of ice. Not a kid. Not one of the new, desperate pilots thrown into the meat grinder. This was a professional, the kind who had probably laughed at P-47s over schnapps not long ago.

“Danny, you still with me?” Jack gasped.

“Trying to get an angle,” Danny replied. “He’s good at shaking me. Keeps forcing me out of position. I get near his six, he rolls out and uses the sun. Half a second later, I’m defensive. I don’t like it.”

“Join the club.”

The dogfight had drifted slightly away from the main bomber stream now. For a moment, it was just three fighters tracing loops and spirals high above central Germany.

The German made his first real mistake when he got greedy.

Jack caught a glimpse of a P-38 limping away, smoke trailing. The 109 broke off him for a heartbeat, rolled toward the wounded twin-engine fighter, tried to snap in a quick kill.

It was a logical move. One less enemy in the sky. One more notch on his scoreboard. But in that split second, he lost sight of Jack.

And Jack, battered Jug and all, was waiting.

He rolled after the 109, not directly— that would take too long— but along a shorter arc. The Jug’s heavy nose dipped, his airspeed jumped. He pulled up, fingers white on the stick, lining up the sight.

For a heartbeat, the 109 filled the circle in his gun glass. Not perfectly— a little far, maybe three hundred seventy yards— but this was as good as it was going to get.

Jack exhaled, steadied, squeezed.

The Jug convulsed as eight Brownings roared. A lance of fire leapt across the intervening air.

The German ace tried to roll out, but the stream caught his right wing root and fuselage. Pieces flew. Smoke billowed. The 109 rolled inverted, then snapped upright again, trailing a thick black line as it dove.

Jack watched, breath held, as the 109’s pilot fought to keep his machine level. For a moment, it looked like he might pull it out.

Then the wing separated.

The fighter cartwheeled, broke apart, and vanished into a distant gout of dark smoke on the fields below.

A small, white dot appeared a moment later— a parachute. Even from this height, Jack could see it jerk as the canopy blossomed.

“Two,” he murmured, though he knew the debriefers would count this one different. This wasn’t just another tally. This was the man who’d come to kill him.

“Murphy, you crazy Irishman,” Danny said, his voice caught between awe and relief. “You got him. I saw it. You got him.”

“Don’t start knitting me a medal yet,” Jack said. “We’re not home.”

He glanced at his fuel gauges and winced. The dogfight had burned more gas than he’d like. Mary Jane II had taken more hits, too; the engine sounded just slightly off, a subtle cough under the hum.

“Blue flight, form up if you’re still with me,” he said. “We’re heading west. The bombers can finish this one alone.”

Two voices answered; one didn’t. Samuels hadn’t replied in a while.

Jack fought down the familiar stab of guilt. There would be time for that later. If he started counting the empty bunks every time he climbed into the cockpit, he’d never get off the ground.

The flight west was a long, quiet slog. The English coast at last appeared as a smudge on the horizon, then solid land. Jack’s hands relaxed slightly on the stick.

Mary Jane II landed with a bounce, rolling out on the grass with her right main gear protesting. Mechanics waved them in, their faces tight until they saw the Jug was in one piece.

Jack throttled back, flipped switches, and the big prop spun down with a final sigh.

When he dropped to the wing, his legs shook. Not all of it was adrenaline.

His crew chief, Sergeant O’Malley, looked up at the canopy and whistled low.

“Mother of mercy, Lieutenant,” O’Malley said. “What’d you do, wrestle a flak battery?”

The Jug’s right wing was peppered with holes. One panel hung partly free, flapping gently. There were scorched streaks on the fuselage where rounds had skipped. A piece of a 20mm shell was embedded in the armor plate behind the cockpit, inches from where Jack’s spine had been.

“She took care of me,” Jack said, patting the side of the fuselage. “Again.”

Danny slid down from his own cockpit, helmet under his arm.

“Told you the bathtub can swim,” Danny said weakly.

They joked, because the alternative was sitting down in the grass and shaking.

Later, in the debriefing room, the intelligence officers played back the gun camera film frame by frame. The room filled with the familiar monochrome flicker of fighters dancing, spitting fire.

“That’s one 190, one 109 early, and…” the intel officer paused as the final sequence came up. “Well, well. That last one is definitely the ace we’ve been hearing about. Tail markings match. That’s Oberstleutnant Klaus Reimer, group commander. They’ve had him credited with over seventy kills.”

The room murmured.

“Guess he won’t be gunning for you anymore,” Danny said softly.

Jack watched the film image of the 109 breaking apart, the tiny white parachute blossoming.

“I hope he survives,” Jack said quietly.

Danny stared at him. “You hope he— after all that—”

Jack shrugged, eyes still on the screen.

“If he lives,” Jack said, “he’ll have to sit in some POW camp and explain to his buddies how his ‘useless’ P-47 bathtub shot him out of the sky. That might do more damage than if he’d gone in with his boots on.”

The room laughed, but there was respect in it.

The next morning, the blackboard in the ops hut changed again.

Under “Mary Jane II – 42-74819 – Lt. J. Murphy,” the chalk now read:

39 CONFIRMED – JUNE TOTAL

At the bottom, someone—probably Danny—had drawn a little German pilot shouting “Badewanne!” with a Jug looming behind him.

The magazine photographer did come, eventually.

He was a young guy from New York, hair slicked back, wearing a clean jacket that looked wildly out of place among oil-stained mechanics and mud. He posed Jack beside Mary Jane II, asked him to fold his arms just so, to put one foot up on the tire, to look off into the distance like he was thinking about home.

“What are you thinking about, Lieutenant?” the photographer asked, lining up his shot.

Jack squinted at the horizon, where silver streaks in the high blue marked bombers heading east again.

“I’m thinking about how a month ago, people laughed at this airplane,” Jack said. “And how they still do, sometimes. They see a big, ugly jug and assume it’s slow, dumb, easy.”

The photographer lowered his camera slightly. “And you?”

“I’ve seen what happens to people who underestimate it,” Jack said. “I’ve seen our boys come home in a Jug that’s missing half its tail and chunks of wing, the pilot white-knuckled and breathing hard, and that engine still pulling. I’ve watched German fighters dive after us and realize, too late, that we dive faster than anything they’ve got. I’ve watched them try to break away and not make it.”

He took a breath.

“People can call it a flying bathtub if they want,” he said. “Personally, I kinda like it. Bathtubs keep you afloat when there’s a whole lot of water trying to drag you under.”

The photographer smirked. “That’s quite a line, Lieutenant. Mind if I quote you?”

Jack shrugged. “Just spell the crew chief’s name right. He’s the one who keeps this crate together.”

The article, when it came out weeks later, was titled something like: “The Jug That Wouldn’t Quit: Thunderbolt Pilot Downs 39 Enemy Planes in One Month.” Stateside readers marveled at the statistics. Mothers clipped it for scrapbooks. Mechanic crews pinned the picture up in their huts, not because of Jack’s face, but because Mary Jane II’s battered nose art was front and center.

Caldwell, the Mustang pilot, saw a copy in the mess tent.

He walked over to Jack’s table, magazine folded under his arm.

“You know,” Caldwell said, “I used to think you were crazy for defending that bathtub.”

Jack sipped his coffee. “Used to?”

Caldwell smiled thinly. “Now I think you’re crazy for flying it that hard and still walking around on two legs.”

He slid the magazine across.

“I lost a man last week,” Caldwell said quietly. “New kid. Flak hit his wing tank. He bailed out okay, but watching that Mustang fall apart after a few hits… I kept thinking about your Jug taking punishment that would’ve shredded ours. We might be faster and prettier. But I’m starting to see why your boys swear by that radial.”

Jack nodded. “Mustangs have their place. We’ve got ours.”

Caldwell exhaled.

“Word is, the Germans have orders now: ‘Avoid Thunderbolts in dives. Do not assume they are easy.’ Their own pilots were complaining in an intercepted briefing: ‘The heavy American fighters we laughed at killed more of us this month than the light ones.’”

“Good,” Jack said simply.

Caldwell hesitated, then offered his hand.

“Here’s to useless bathtubs,” he said. “And the maniacs who fly them.”

Jack shook it. For the first time, there was no hint of mockery in the Mustang pilot’s eyes.

Years later, long after the war, when the sky over Europe had gone back to hosting only clouds and passenger liners, an old man named Jack Murphy sat in a lawn chair behind a small house in Ohio, watching his grandkids run around with model airplanes.

They argued— fiercely, as kids do— about which plastic fighter was better.

“The Mustang’s faster!” one boy shouted. “It’s the coolest!”

“The Jug’s tougher!” another retorted, waving a stubby-winged model. “Look, Grandpa flew one of these. The magazine says so.”

“That thing looks like a garbage can with wings,” the first kid snorted.

Jack laughed, a deep, rusty sound.

“Careful, kiddo,” he said. “I’ve heard that before.”

The boys looked over.

“Grandpa, which one was really better?” the Mustang fan asked.

Jack thought of the German voices on the radio. Of Caldwell’s smirk turning into respect. Of Mary Jane II groaning in a max G pullout, wings flexing, engine roaring. Of thirty-nine black crosses marked in chalk on a board in a damp hut, and all the faces behind them— some he saw bailing out under silks, some he never saw again.

He thought of walking away from the flight line one twilight and seeing his Jug silhouetted against the sun, scars and all, looking, for a brief second, like something holy and battered and stubborn.

“They were both good at what they did,” he said finally. “The Mustang could go far and fast. The Jug could take a beating and hit like a freight train. But I’ll tell you something the numbers and the magazines never quite did.”

The kids leaned in.

“What?” the model Jug pilot asked.

“The best airplane is the one that brings you home,” Jack said. “And for one very long, very hard month, there was a so-called ‘useless bathtub’ that not only brought me home, but made a lot of men on the other side stop laughing.”

He picked up the plastic P-47 from his grandson’s hand, turned it between his fingers, traced the stubby wings.

“They said it couldn’t climb. They said it couldn’t dogfight. They said it was a waste of metal,” he murmured. “But that ugly brute chewed up thirty-nine fighters in thirty days when the sky was as dangerous as it’s ever been.”

He smiled, lines around his eyes deepening.

“Funny thing about war,” he said. “It has a way of making you eat your words. Especially if those words are ‘useless’ and they’re aimed at a Thunderbolt.”

The boys went back to their game, swooping and diving, making engine noises with their mouths. Jack leaned back in his chair, eyes half-closed, hearing echoes in the summer air: the roar of a big radial, the rattle of eight .50s, the crackle of a German pilot’s voice calling something a flying bathtub before going suddenly, permanently silent.

He had lived long enough to see the Jug in museums now, polished and roped off, kids pressing their faces against glass to stare at the bulky fighter that didn’t look like much until you read the plaque beneath:

REPUBLIC P-47D THUNDERBOLT – “THE JUG”

ONE OF THE MOST RUGGED FIGHTERS OF WORLD WAR II

COULD ABSORB TREMENDOUS DAMAGE AND STILL RETURN HOME

FAMOUS FOR ITS ROLE IN AIR SUPERIORITY AND CLOSE SUPPORT

The plaques never mentioned the laughter. Or the radio insults. Or the way some of their own allies doubted them.

But Jack remembered.

And somewhere, he liked to imagine, in a house in Germany, an old man with pale eyes and a scar on his arm remembered too— not the number thirty-nine, but the day his own certainty had broken apart under the guns of a “useless” P-47 that refused to die quietly.

News

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load