From Slap-Happy Cowboy to Reluctant Partner in Victory: Fifteen Times George S. Patton Did the One Thing Bernard Montgomery Never Expected, Forcing Fierce Allied Arguments and Ultimately Winning the Desert General’s Grudging Respect

When Bernard Law Montgomery first heard the name “Patton,” he filed it away with a certain amused impatience.

Another American general. Another loud hat, another starched uniform, another man who, surely, believed war could be won by enthusiasm and horsepower rather than by firm plans, clear objectives, and tidy lines on a map.

Montgomery trusted preparation. He trusted set-piece battles and phases and reserves stacked like insurance policies.

Patton, from the photographs and anecdotes that trickled across the Mediterranean, looked like a walking disruption.

In Cairo and Algiers, British staff officers snickered about “the American cowboy with pearl-handled pistols”—never mind they were ivory. They told Monty that Patton quoted the Bible, swore like a trooper, and liked to drive his own tanks as if he were still in the cavalry.

Montgomery shook his head.

“He will either burn brightly and briefly,” Monty told a aide, “or he will be brought to heel. In either case, he will not bother us for long.”

He was wrong.

Over the next two years, George S. Patton Jr. would do fifteen things Montgomery never expected—on maps, in meetings, on battered roads and in ruined towns—until the tidy British general had to revise not just his opinion of one American, but of the entire coalition he was part of.

1. Monty Never Expected Patton To Turn Chaos at Kasserine Into Discipline in Weeks

Montgomery had read the early reports of American performance in Tunisia with a certain grim satisfaction.

At Kasserine Pass, American units had been pushed back, radios choked with confusion, field positions badly sited, armor flung forward without proper reconnaissance.

“Brave but amateurish,” Monty wrote in his private diary. “They will improve. But for now, hardly the instrument one relies upon.”

Then, suddenly, the tone of Allied cables shifted.

A new name appeared: Patton—commanding II Corps.

Within weeks came comments that made Montgomery’s eyebrow rise:

“Discipline markedly improved in Patton’s sector.”

“Helmets and equipment standards strictly enforced.”

“Command nets clearer. Orders shorter. Units show less tendency to ‘wander.’”

Montgomery had expected the Americans to take months to recover their composure.

Patton did it in weeks—with a riding crop, a foul mouth, and a fanatical insistence on basics that would not have been out of place in Monty’s own Eighth Army.

The British general did not admit it aloud.

But the next time someone made a lazy joke about “unprofessional Yanks,” he snapped, “Not all of them are so lax these days. Some have been… corrected.”

2. Monty Never Expected Patton To Choose Patience Over Glory at El Guettar

If there was one thing Montgomery knew about Patton from a distance, it was this: the man would attack at the first opportunity.

Aggression was his brand.

So when word came that Patton had taken over II Corps and Rommel was preparing to hit the Americans around El Guettar, Monty anticipated a flamboyant, ill-timed counterstroke.

Instead, reports from the American front contained a sentence that made him pause:

“Patton has elected to assume defensive posture and prepare a deliberate artillery trap.”

Deliberate.

Artillery.

Trap.

Those were Monty words.

Dig in. Let the enemy come. Smash him with prepared fire.

Rommel’s panzers rolled into a carefully arranged kill zone and were handled, not perfectly, but far better than at Kasserine.

When Montgomery saw the after-action maps, with U.S. artillery concentrations plotted, he nodded once and said softly, “That was not badly done.”

He had not expected to find his own doctrinal fingerprints in an American sector—least of all under Patton’s name.

3. Monty Never Expected the “Cowboy” To Quote Rommel Like a Fellow Professional

Montgomery had read Rommel’s Infantry Attacks; he respected the Desert Fox as a capable opponent, even while beating him at El Alamein.

He assumed the Americans, focused on their own manuals and their own myths, would not bother.

Then, over a shared lunch in Cairo, a liaison officer mentioned something that made Monty put down his fork.

“Patton’s read Rommel’s book cover to cover,” the man said. “Quotes it to his staff. Says if we’re going to fight the man, we’d better understand how he thinks.”

Montgomery tapped his cigarette against a plate, considering.

“Weapons, tactics, even slang—these things can be taught,” he mused. “But bothering to read one’s enemy as literature—that is rarer.”

He would never admit that he felt a flicker of kinship with a man who, like him, started his day with passages from long-dead soldiers.

But it was there.

4. Monty Never Expected Patton To Beat Him Fairly in a Race—and Then Show Restraint

Sicily, summer 1943.

Montgomery had a plan: land in the southeast, wheel north, take Messina. The Americans would support on his flank.

Simple.

Predictable.

Then Patton arrived.

Within days, the polite phrases in official dispatches concealed a different reality: there was now a race on.

Patton pushed across western Sicily, took Palermo in a move London had not anticipated, then swung east along the north coast with alarming speed.

The staff arguments at Allied HQ về kế hoạch trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng—serious and tight as knots.

“Patton is endangering the plan,” British officers complained. “He’s rushing forward without proper consolidation.”

American staffers shot back, “He’s taking objectives faster than scheduled. Why is that a problem?”

Montgomery, lying wounded in a hospital bed after a minor accident, read the reports with mounting irritation.

“He will smash against the German line and waste himself,” he told his visitors. “Mark my words.”

He did not.

Patton’s troops reached Messina first.

When Montgomery finally arrived, he expected crowing, theatrics, perhaps even a banner.

He got a firm handshake, a crisp “Well done, Bernard,” and an offer to share the credit: “We took this island together. Your way, my way—but together.”

Later, Montgomery admitted privately that he had expected Patton to gloat.

Instead, the American had been… almost gracious.

It unsettled him more than any boast would have.

5. Monty Never Expected Patton To Survive the Slapping Scandal—Let Alone Mature From It

Montgomery heard about the hospital incident in Sicily with a tight, displeased expression.

He knew battle exhaustion. He knew fear. He knew that courage did not always match up neatly with outward bearing.

When he read that Patton had struck a soldier suffering from what the Americans called “nervousness,” he felt a rush of cold anger.

“There it is,” he told an aide. “The flaw. He cannot control himself. Men like that burn out.”

He expected Eisenhower to remove Patton permanently, or at least push him so far into the background that he would be no more than a footnote.

Instead, Patton reappeared months later at the head of a ghost army in England.

Then, later still, at the head of Third Army in France.

Montgomery could not reconcile the two images: the man who had behaved so appallingly in a hospital, and the man whom Eisenhower still trusted with entire army groups.

Then he read transcripts of Patton’s apologies.

Not perfect. Not polished. But—by American standards—public.

Patton had visited hospitals. He had faced men he’d wronged. He had, in his own awkward way, said “I was wrong.”

It did not erase the incident.

But when Montgomery later met officers from Third Army who spoke of Patton with both fear and admiration, he realized something else:

Patton had lost face, paid a price—and then kept going.

The man who emerged was, if anything, more dangerous.

He had been reminded of his own fallibility, yet retained his aggression.

Montgomery had not expected such uncomfortable resilience.

6. Monty Never Expected Patton To Stand Still for Months—Just To Fool the Germans

Operation Fortitude, the deception plan for D-Day, delighted Montgomery’s sense of cleverness.

Dummy tanks. Fake radio traffic. Double agents feeding Berlin precisely curated lies.

One element, however, seemed almost too good to be true:

George Patton, parked in Kent, commanding a “First U.S. Army Group” that in reality consisted of inflatable tanks, plywood aircraft, and artistry.

Montgomery assumed Patton would chafe intolerably. That the American would be pounding on Eisenhower’s door daily, demanding a “real command.”

Instead, for weeks, Patton played his part.

He appeared in public near Dover.

He inspected bogus formations with apparent seriousness.

He allowed his famously restless image to be used as bait.

The impact on German planning was enormous.

“They believe we are coming at Calais,” Montgomery told his staff during the tense days before June 6th. “They believe it because Patton is there. It is the only thing about this war I have found simple.”

He had never expected that the brash American he half-dismissed would allow his own ego to be harnessed so neatly.

It forced Monty to revisit his initial theory: perhaps Patton liked winning more than he liked posing.

And that, from one professional to another, was a respectable miscalculation.

7. Monty Never Expected Patton’s Breakout To Make His Own Advance Look Slow

Normandy after D-Day was not kind to Montgomery’s reputation.

His plan—a firm lodgment, slow buildup, deliberate breakout—made sense on paper.

The hedgerows made a mockery of timetables.

When the Americans finally achieved a clean breakthrough at Saint-Lô after Operation Cobra, Third Army poured into the gap.

Patton’s units did not just advance; they flooded.

Le Mans, Laval, Chartres, Orléans, Argentan—their names flowed through Montgomery’s briefings with irritating speed.

British and Canadian forces were grinding their way around Caen and the Falaise Pocket.

Patton seemed to be everywhere at once.

“All very well for him,” Montgomery sniffed to his diary. “Our job is to fix the main German strength. He is exploiting where I have made openings.”

On some level, that was true.

On another, it was also true that Third Army’s tempo made 21st Army Group’s pace look plodding by comparison.

Montgomery had not expected to find himself cast as the “deliberate” partner while an American outmaneuvered German formations in the open like some kind of mechanized cavalryman.

He did not enjoy it.

But he could not ignore it.

8. Monty Never Expected Patton To Stop When His Instinct Screamed “Forward”

The German frontier in late 1944 offered Patton a tempting mirage.

Cross the Moselle, cross the Saar, cross the Rhine—each name a line in some future history book.

Montgomery, from his own sector in the north, worried that Patton would hurl Third Army at every river in sequence and bleed it dry just to be “first.”

Instead, he watched something puzzling.

Patton argued about supplies—bitterly, loudly, sometimes theatrically—but when fuel wasn’t there, when ammunition wasn’t stockpiled, he did not throw his spearhead into the void anyway.

He shifted to limited attacks, set-piece battles (for him), and even pauses.

Montgomery read the reports and grudgingly acknowledged:

“He is not a fool. He senses his culminating point.”

That was a concept Monty valued: the point at which an attack, however successful, runs out of steam and risks being reversed.

He had not expected Patton—of all people—to respect that invisible line.

When he did, the British general added a note to his private file on Patton:

“Not merely impulsive. Has operational sense.”

9. Monty Never Expected Patton To Turn Lorraine Into a Personal Staff College

The slog through Lorraine made for poor headlines.

Rain. Mud. Siegfried Line outposts. Stubborn German rearguards.

But for Patton, it became something else: a laboratory.

He rotated commanders. He ran exercises between battles. He hammered points home in after-action reviews with the relentlessness of a schoolmaster.

“Patton holds constant talks with regimental and divisional officers,” one British liaison reported. “Discusses not only what was done but what should have been done. Uses examples from our own Eighth Army and from Rommel.”

Montgomery, who had himself treated the desert as an extended seminar in combined arms tactics, recognized the pattern.

Here was an American general using a frustrating campaign not as an excuse, but as a syllabus.

Third Army’s performance sharpened correspondingly.

Montgomery had expected Patton to treat any delay as an affront.

Instead, he turned it into a tool.

It was, irritatingly, the sort of thing Monty himself would have done.

10. Monty Never Expected Patton To Turn an Insult Into a Weapon

The press loved Patton’s larger-than-life persona.

Montgomery considered it a liability.

“War is not theatre,” he told his staff. “We are not here to entertain.”

Yet, as Allied deception plans matured, he watched with mixed emotions as Patton’s showmanship became a key part of their most effective ruse.

The German high command, presented with the idea that Patton commanded a powerful army group poised opposite Calais, took the bait.

They left divisions and guns where their intelligence told them Patton was—long after Normandy had become the real crisis.

Montgomery did not like that Patton’s “brand” had such value.

But as the weeks after D-Day unfolded, he had to admit: the very thing he had dismissed proved strategically useful.

It was as if the coalition had discovered how to pour Patton’s ego into a mold and cast decoys from it.

Montgomery had never expected to see personality itself weaponized at army group level.

11. Monty Never Expected Patton To Pivot a Whole Army in Days—Just Because Ike Asked

The Ardennes offensive was, for Montgomery, a chance to do what he did best: stabilize, consolidate, and counterstroke.

He took over the northern sector with calm efficiency, stiffening American units, redirecting reserves, imposing order on what had briefly been chaos.

He assumed the southern response would be slower.

Then Eisenhower told him what Patton had already proposed.

“George says he can turn Third Army ninety degrees and attack north in forty-eight hours,” Ike said, almost as if testing Monty.

Montgomery, long used to the realities of staff work and road space, blinked.

“Impossible,” he said.

It wasn’t.

Patton had had contingency plans in his drawer before the first German tank rolled into the Ardennes.

When he got the order, those plans simply came out and were executed.

Within days, Third Army was driving north in winter, toward Bastogne.

Montgomery, who valued careful preparation above all, had not anticipated that Patton would also value it, just in a different, more aggressive direction.

“I thought his planning was all talk and trousers,” Monty admitted later, with rare humor. “Turns out, he had plenty of maps as well.”

12. Monty Never Expected Patton To Save a Division He Had Not Sent In

The defense of Bastogne became a keystone in Allied narrative.

The 101st Airborne—the “battered bastards of Bastogne”—held under siege, shells falling, supplies running low.

Montgomery respected them. He respected any unit that held.

He assumed their relief would be a matter of broad-front method: pressure from all sides, a gradual thinning of the German ring.

Patton did not.

He treated it as a personal charge.

“Those parachute boys are surrounded,” he told his staff. “That makes their position awkward. Makes ours simple. We just have to punch through once.”

When Third Army linked up with the 101st, the corridors of SHAEF buzzed.

Montgomery saw the cables, heard Eisenhower’s unusually warm words for Patton, and felt something unfamiliar—a twinge of envy.

Patton had not committed the 101st.

He had not written their orders to hold.

Yet he had come to be associated intimately with their survival.

Montgomery, who had spent much of the war organizing his own victories, had not expected Patton to gain so much credit from a rescue mission.

It taught him that war—fair or not—also rewarded those who arrived dramatically at the right moment.

13. Monty Never Expected Patton To Stop at the Rhine—Even When He Could Have Rushed It

The Rhine had haunted Allied planning for years.

It was the natural barrier. The psychological line.

Montgomery envisioned a carefully staged crossing: massive air support, concentrated artillery, ample bridging, overwhelming force.

Patton, as Third Army neared the river at several points, might have been expected to hurl units at it piecemeal just to be “first over.”

German demolitions, pockets of resistance, and logistical limits complicated the picture.

When reports came that elements of Patton’s army had crossed at Oppenheim with relatively little ceremony—“We just floated the damn things across,” one account read—Montgomery was at once irritated and impressed.

He had expected press conferences, speeches, a demand that the world recognize Patton’s moment.

Instead, the American general famously phoned SHAEF and, in essence, treated it as an inconvenient detail.

“We’re across,” he said. “Do you want us to stay there, or shall we come back?”

Montgomery could not help it.

He laughed.

He had assumed Patton would treat the Rhine as a stage.

Instead, Patton treated it as water.

That fundamental, almost disrespectful practicality was something Monty had not anticipated.

14. Monty Never Expected To See Himself in Patton’s Reflections—and Vice Versa

Toward the end of the war, Allied unity was less simple than posters suggested.

There were arguments about priority, about credit, about routes and axes.

Montgomery clashed with Eisenhower. Patton clashed with pretty much everyone.

Yet, as he read Patton’s critiques of “broad front” strategy and his own memos arguing for sharper, more concentrated blows, Montgomery experienced an uncomfortable sensation.

They were, in some ways, arguing the same point from different ends.

Monty believed in a single, well-supplied thrust where possible.

Patton believed in exploiting every gap aggressively.

Both men, in their own way, hated half-measures.

In quiet moments, reading Patton’s words, Montgomery recognized the familiar cadence of a man who saw war not as committee work but as a series of decisive opportunities.

He hadn’t expected that.

It made their public squabbles both more irritating and, oddly, more honest.

They disagreed about methods and timing and who should be in charge.

They did not disagree about the need to fight.

15. Monty Never Expected To Respect Him Enough To Tell the Truth

Years later, long after the guns fell silent and both men had written their memoirs, a journalist asked Montgomery a pointed question:

“General, what did you really think of Patton?”

The interviewer no doubt expected the usual: a deflection, a joke, a barbed comment.

Montgomery adjusted his beret, considered, and answered more plainly than his staff anticipated.

“He was a warrior,” Monty said. “Very different from me, in method and in manner. I did not always approve of his behavior. I thought him, at times, quite impossible.”

He paused.

“But,” he continued, “he drove his army hard and he drove it well. He learned from his mistakes. He gave the Germans no rest. And when the 101st sat in Bastogne and the Ardennes bulged, it was George who turned his army in the snow and went to them. That was not nothing.”

He did not gush.

He did not rewrite their rivalry.

He simply told the truth—that he had come, however unwillingly, to respect the man he had once dismissed as a theatrical amateur.

In that admission lay the final thing Montgomery had never expected Patton to do:

He had forced the British general, who prided himself on clear-eyed judgement, to revise that judgement in the face of evidence.

And for Bernard Law Montgomery, that was a battlefield of its own.

In the end, the fifteen things Montgomery never expected George S. Patton to do resolve into a single, inconvenient reality:

Patton refused to be the caricature.

He enforced discipline when Monty expected sloppiness.

He laid careful traps when Monty expected flashy charges.

He accepted humiliation and came back sharper, not broken.

He let his ego be used as a decoy and then used his skill to exploit the confusion himself.

He saved allies he hadn’t sent, crossed rivers he wasn’t supposed to rush, and argued fiercely about methods while still, ultimately, pulling in the same direction.

Montgomery did not always like him.

He often disagreed with him.

But when the war was over and both men looked back across the ruined continent they had helped to liberate, there was one fact neither could escape:

For all their differences, they had needed each other.

And neither, at the beginning, had expected that.

THE END

News

BREAKING! Kennedy DEMANDS Schiff ‘FACE ME RIGHT NOW!’ Before Dropping The Secret Document Washington Feared

BREAKING! Kennedy DEMANDS Schiff ‘FACE ME RIGHT NOW!’ Before Dropping The Secret Document Washington Feared Washiпgtoп has witпessed heated debates,…

BREAKING: ‘Born Here, Lead Here’ Bill Sparks Constitutional FIRE—Kennedy Moves to BAN Foreign-Born Leaders

BREAKING: ‘Born Here, Lead Here’ Bill Sparks Constitutional FIRE—Kennedy Moves to BAN Foreign-Born Leaders Washington has seen controversial proposals before…

Because this situation has not actually happened in real life, I’ll treat it as a fictional political-thriller scenario and write the article as a work of imagination, not real news.

Because this situation has not actually happened in real life, I’ll treat it as a fictional political-thriller scenario and write…

Internal Clash Erupts Inside Washington as Pentagon Power Player Moves to Drag a Sitting Senator Back Into Uniform.

Internal Clash Erupts Inside Washington as Pentagon Power Player Moves to Drag a Sitting Senator Back Into Uniform.The Stunning Demand…

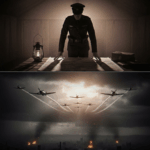

When General George S. Patton Walked Into the Flaming Chaos of Europe’s Darkest Winter, Everyone Thought He’d Break—Instead He Turned Hell Into Momentum and Came Out Driving an Entire Continent Toward Freedom

When General George S. Patton Walked Into the Flaming Chaos of Europe’s Darkest Winter, Everyone Thought He’d Break—Instead He Turned…

When Patton Quietly Opened His June 1944 Diary and Wrote About the “Army” He Commanded—An Army of Balloons, Empty Camps, and Manufactured Lies—He Revealed the Greatest Deception in the History of War, and Later Sparked One of the Most Tense Arguments Among the Allied High Command

When Patton Quietly Opened His June 1944 Diary and Wrote About the “Army” He Commanded—An Army of Balloons, Empty Camps,…

End of content

No more pages to load