Fainting in My Cap and Gown, Being Left Behind by the People Who Raised Me, and the Unexpected Fight for My Own Future That Started Under Fluorescent Lights in a Crowded Hospital Emergency Room

WHEN I COLLAPSED AT MY GRADUATION CEREMONY, THE DOCTORS CALLED MY PARENTS. THEY NEVER CAME. INSTEAD, a stranger reached for my hand in the waiting room and said, very simply, “You’re not alone, okay? Not today.”

At first, I thought I was still dreaming.

The ceiling over me was a blur of white tiles and harsh, buzzing lights. My ears rang with an alarm I couldn’t see. Something squeezed my arm. A cool wind brushed my face.

Then voices came into focus.

“Blood pressure’s dropping.”

“Keep her talking.”

“Miss? Can you hear me? What’s your name?”

My mouth moved before I could think. “Lia,” I whispered. My tongue felt heavy. “My name is Lia.”

“Okay, Lia. I’m Ben. I’m a paramedic,” a calm male voice said near my left ear. “You’re going to be okay. You passed out at your graduation. We’re taking you to the hospital. Just stay with me.”

Graduation.

The word hit me harder than the actual fall.

I tried to lift my head, tried to imagine the gymnasium stage I had worked four years to reach. The school colors. The folding chairs. The buzz of air conditioning that never quite kept up with the June heat. The sea of black gowns, mortarboards, and families holding bunches of flowers wrapped in shiny plastic.

My family should have been in that crowd.

Even with my eyes closed, I could see the seats where they were supposed to sit. Row 5, near the middle, because Mom didn’t want to be too close to the aisle where people would “bump into her with their backpacks.” Dad would be straightening his tie, checking his work email between speeches, pretending it was “urgent” when really he just hated sitting still.

“Mom,” I murmured. “I—I need my parents…”

“We’re calling them now,” Ben said. “They’ll meet you at the hospital, okay? Just breathe. Can you tell me if you’re in pain anywhere?”

I tried to scan my body. My chest felt tight, like someone had stacked textbooks on it. My head pounded. My hands tingled. My gown clung to me, damp with sweat.

“I can’t… I can’t really breathe,” I managed.

“You’re breathing,” he replied gently. “Slow, but you’re breathing. You might be having a panic episode and also got dehydrated standing in that line, but we’re going to check everything. Just focus on my voice. What did you graduate in, Lia?”

“Business,” I said automatically, the way I’d said it to relatives, professors, strangers. “Top of… top of my class.”

I heard a low whistle. “Impressive. You must have worked really hard.”

My brain fluttered around the word “worked” like a trapped bird. Late nights. Early mornings. Color-coded planners. Highlighters lined up on my desk. My mother’s voice over the phone at midnight: Top of the class or you might as well not go at all, do you understand?

I let myself sink into the movement of the stretcher, the sway of the ambulance. I tried not to think about the phone call my parents would be getting.

I tried not to think about whether they would answer.

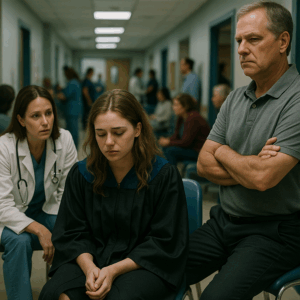

The emergency room was colder than the gym had been, but somehow it felt harder to breathe.

I lay on a narrow hospital bed, the rails up on both sides, an IV taped to the back of my hand. Machines hummed and beeped around me. Nurses moved briskly, their conversations overlapping: room numbers, blood work, x-rays, lunch schedules. Everything had a rhythm I couldn’t follow.

A nurse with smooth brown skin and neat braids leaned over me. Her name tag said “T. Harris, RN.”

“How you doing, Lia?” she asked, adjusting a monitor. “On a scale of one to ten, what’s your chest feeling like now?”

“Five?” I guessed. The pressure had loosened a little, but my heart still skipped like it couldn’t decide how fast it wanted to go. “My head hurts more now, though.”

“That can happen. Your labs are running,” she said. “The doctor will be back soon. Your vital signs are already looking better.”

“Did… did anyone call my parents?” I asked.

She glanced at the chart on the side of my bed. “We called the number you listed as your emergency contact,” she said carefully. “Your mother’s number, right?”

“Yes,” I said. “Did she…?”

“She answered,” Nurse Harris said. Her voice stayed professional, but her eyes softened. “I let her know what happened and that you’re stable and being evaluated. She said she appreciated the call.”

I waited. The silence stretched.

“And?” I pressed.

“And she said she and your father were… unavailable to come right now,” the nurse said. “But they’d check in later.”

It felt like all the air left the room.

“Unavailable?” I repeated. “My mom said she’s unavailable?”

“I’m sorry,” the nurse said quietly. “She mentioned your graduation ceremony and said there was some, uh, scheduling conflict. I’m just relaying what she told me.”

A scheduling conflict.

I pictured my mother glancing at the unknown number, lips tightening, stepping out into the hallway away from the ceremony she’d already told me was “a formality.” I saw my father checking his watch, his expression caught somewhere between irritation and boredom.

Of course they were “unavailable.”

Of course.

I stared at the white blanket over my legs. Suddenly, my cap and gown felt like costumes from a play I’d accidentally walked into. The Latin honors cords around my neck—now resting in a plastic bag on the floor—felt like props.

They didn’t come to the hospital.

They weren’t coming.

Nurse Harris hesitated like she wanted to say more, then just patted my arm. “You’re not alone here, though,” she said. “We’re going to take good care of you.”

I nodded, because I didn’t know what else to do.

After she left, the curtain around my bed rustled and a middle-aged man stepped through. He wore dark slacks, a button-down shirt, and the kind of face that looked like it smiled often, even when it wasn’t currently doing it.

“Hey there,” he said, holding up both hands like he wanted to show he meant no harm. “I’m Dr. Patel. I’m one of the attending physicians in the emergency department. Mind if I sit?”

I shook my head.

He pulled a stool closer and sat near the foot of the bed, flipping through my chart. “So, you had quite a morning,” he said. “Collapsed on stage, ambulance ride, first IV. That’s a lot at once.”

“I was really looking forward to posing for nice diploma pictures, not… this,” I muttered.

“I can imagine,” he said with a small sympathetic smile. “We ran some tests. Your heart looks structurally normal. Your blood work shows you’re dehydrated, your blood sugar was low, and your stress hormones are through the roof. Have you been pushing yourself hard lately?”

I laughed once, a bitter little sound. “Define ‘lately.’”

He nodded, like that answer didn’t surprise him. “I’m guessing not a lot of sleep, not a lot of real meals, a lot of pressure?”

“That’s just… life,” I said. “I graduated top of my class. It’s not like that happened by accident.”

“True,” he said. “But your body also isn’t a machine. Sometimes it decides to shut down before you decide you’re done.”

“You’re saying I did this to myself,” I muttered.

“I’m saying your body is waving a giant red flag,” he replied, still gently. “We’re going to observe you for a while, make sure your heart rhythm stays stable, and talk about follow-up care. I also want you to consider talking to a counselor about stress and anxiety. This kind of event can be a wake-up call.”

“A wake-up call,” I repeated. It sounded like a phrase my father would use in a performance review.

Dr. Patel glanced once more at the chart. “I see we called your parents. Do you have any other family or friends you’d like us to reach out to? You’re technically an adult, so you get to decide.”

Something in the way he emphasized “you” made my throat tighten.

“My best friend, Rosa,” I said. “She was at graduation. I don’t know where she–”

“I’m here, you idiot.”

The curtain burst open and Rosa slipped inside, her graduation cap askew, curl-framed face flushed. Her gown was unzipped, revealing her bright yellow dress underneath. Mascara had smudged under both eyes like she’d cried and then wiped it away with the back of her hand.

She rushed to my bedside, grabbing my free hand. “Do not scare me like that again,” she said, half whisper, half growl.

Something inside me finally cracked. I squeezed her hand, and suddenly the room blurred again, this time with tears.

“You missed your name,” she said softly. “They called ‘Amelia Tran, summa cum laude’ and you weren’t there to cross the stage. The whole row was whispering, people were looking around. The dean just kind of waved at the empty space.”

“Great,” I croaked. “So I ruined even that.”

“You didn’t ruin anything,” Rosa said firmly. “You collapsed because you’ve been running on fumes since sophomore year. I’ve seen your schedule.”

“I’m going to go check on your admission paperwork,” Dr. Patel said, standing up. “Rosa, right? I’m glad you’re here. Lia should have someone with her.”

He left us, and for a while, we just breathed in sync.

“Your parents on their way?” Rosa asked eventually.

The question landed like a stone in my stomach.

“They said they’re ‘unavailable’ right now,” I said. “So. No.”

Rosa’s face changed. Her brows drew together, her mouth pressed into a hard line. “You have got to be kidding me,” she said quietly.

“I’m not surprised,” I said, trying to sound casual, like it didn’t matter. “They probably have some networking lunch or whatever scheduled. They can’t miss that.”

“This is an emergency room,” Rosa said. “Your heart freaked out and you passed out cold in front of the whole graduating class. That kind of outranks a networking lunch.”

I had no answer to that. Because she was right, and because some part of me had expected it anyway.

A nurse came in and asked Rosa to step out while they checked my vitals again. Once they were done, I was wheeled to a different part of the ER, past other curtained spaces and a loud television locked on a daytime show.

We passed the waiting room on the way. People sat hunched in plastic chairs: a woman with a bandaged hand, an older man clutching his stomach, a young couple whispering urgently. Families. Friends. People there for each other.

My parents were not among them.

Still, as my gurney rolled past, a woman in a light blue cardigan looked up from her magazine and caught my eye. She had gray streaks in her dark hair and laugh lines carved deeply into her face. Something about her expression was so open and kind that I instinctively wanted to apologize for being in a hospital gown and socks.

Our eyes met for only a second.

She gave me the smallest nod. Not a big, dramatic gesture. Just a quiet acknowledgment, like she saw me and wanted me to know that.

It shouldn’t have mattered. But somehow, it did.

They placed me in a small room off the main section, one with a door instead of curtains. I was “under observation” now, which I learned meant a lot of waiting punctuated by occasional visits from nurses and doctors.

Rosa stayed in a chair by my bed until a nurse reminded her visiting hours had limits and she needed to grab food and check in with her own family.

“My mom’s already trying to cook for you,” she told me as she left. “Text me if you need anything. I’ll be back soon.”

After she was gone, quiet settled around me. The TV in my room was off. The hospital hummed with a low drone of HVAC and distant voices. My phone buzzed on the tray table beside me, screen lighting up with a few scattered messages.

One from a class group chat:

Did anyone see what happened to Lia?

Another from my honors advisor:

Heard you had a medical incident at the ceremony. Please let me know you’re alright when you can.

And one from my mother, at last.

It was not a call.

It was a text.

Mom: We heard from the hospital. They said it isn’t life-threatening. We’re very busy with guests who came to see you graduate. We’ll talk later about this.

I stared at the message until the words blurred.

No “Are you scared?”

No “How do you feel?”

Not even a simple “Are you okay?”

Just an agenda item. We’ll talk later about this.

There it was again: that old feeling I’d carried around like an invisible backpack my whole life, filled with bricks I couldn’t put down.

You are a project.

You are a performance.

You are not allowed to make a scene.

I don’t know how long I stared at the screen before I realized there was someone standing in the doorway.

It was the woman from the waiting room—the one in the blue cardigan.

“Oh,” I said, startled, dropping my phone onto the blanket. “Hi. Sorry. I thought you were a nurse.”

She smiled a little. “I get that a lot,” she said. “I think it’s the cardigan. And the sensible shoes.”

There was something light in her voice, but she hovered uncertainly at the door. “I’m sorry, I don’t want to intrude,” she added quickly. “I was just… I saw you rolled past earlier and I overheard that you collapsed at your graduation.”

I blinked. “You overheard that?”

“This place echoes,” she said. “Anyway, my name is Maria Martinez. My younger son is down the hall with a sprained ankle, and I’ve been in that waiting room for three hours now. I was getting coffee and walked by. I just… I kind of wanted to check on you. Is that okay?”

I should have said thank you and waved her away. She was a stranger. People didn’t just wander into patients’ rooms.

But something about her face—the lines around her eyes, the way she didn’t look away when she saw the dried tear tracks on my cheeks—Made me say, “Yeah. Yeah, that’s okay.”

She stepped in, closing the door partway behind her. Up close, I could see she was wearing a simple gold necklace and her nails were painted a soft pink, though the polish was chipped at the tips.

“I promise I’m not weird,” she said. “Or, if I’m weird, it’s the regular kind of weird, not the scary kind.”

A small laugh escaped me, surprising even myself. “That’s… good to know,” I said.

“So congrats,” she continued, settling into the chair Rosa had vacated. “On graduating, I mean. That’s a big deal.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Feels kind of… overshadowed right now.”

“I imagine,” she said. “I saw your friend, the one in the yellow dress, in the vending machine line. She looked like she was about ready to fight the walls for you.”

“That tracks,” I said. “Rosa’s like that.”

“Good,” Maria said. “Everyone needs at least one person who will fight the walls for them.”

Her eyes flicked to my phone. “Family on their way?” she asked, not nosy, just gently curious.

I swallowed. “No,” I said. “They’re… unavailable.”

Her brows rose just a little, but she didn’t say What? or How could they? the way Rosa had. Instead, she nodded, like she was filing the information away.

“Well,” she said slowly. “Then I guess it’s a good thing hospitals have open visiting policies, right? If you don’t mind the company, I can sit here for a bit. My son’s watching sports with the nurse and frankly, I think they’re having more fun without me.”

“You don’t even know me,” I blurted out.

“That’s true,” she said. “But I know what it looks like when a kid is lying in a hospital bed with no parent in sight.

“And I also know what it feels like to be the parent in the wrong waiting room.”

I frowned, not understanding. She waved it off.

“Long story,” she said. “We don’t have to talk about me. We can just sit. Or talk about graduation. Or the terrible coffee.”

We did end up talking, because silence felt too heavy.

She asked what I’d studied. I told her about my major, my honors thesis, the internship I’d already lined up at a consulting firm downtown. The words came out rote, phrases I’d practiced for interviews.

“Impressive,” she said, genuinely. “Do you like it?”

The question caught me off guard. So few people had ever asked that.

“It’s… what I’m good at,” I said.

“That’s not what I asked,” she replied, tilting her head.

I stared at my hands. “It’s complicated.”

“Complicated how?” she prompted gently.

I heard myself before I realized I was truly answering. “My parents came here with nothing,” I said. “They built this whole life from scratch. They work all the time. They pushed me to aim for something bigger, better. I was supposed to become the first real success story in our family. So I picked the path that would make the most money, the one that sounded impressive at dinner parties. It’s what they wanted.”

“What about what you wanted?” she asked.

The question was so simple it almost felt rude.

“What I wanted didn’t really come up,” I said.

She nodded thoughtfully. “My mom used to say that when you’re tired enough, your body will make decisions for you that your mouth is too scared to say out loud,” Maria said. “Sometimes it looks like getting sick. Sometimes it looks like forgetting things. Sometimes, maybe, it looks like collapsing in the middle of the biggest performance of your life.”

“That’s dramatic,” I said, but there was no bite in it. I was too tired.

“Maybe,” she said with a small shrug. “Maybe not.”

We were interrupted when Dr. Patel came back in to review my test results. Maria stood up quickly.

“I’ll step out,” she said. “I just wanted you to know there’s at least one extra mom in the building thinking about you.”

“Thank you,” I said, and I meant it more than I expected.

Later, when the hallway lights dimmed for evening hours, my phone rang.

The caller ID said “Mom.”

I stared at it long enough that it almost went to voicemail.

Then I hit accept.

“Hi,” I said.

“You sound weak,” my mother’s voice said immediately, sharp even through the phone. “What did the doctor say? Is this going to be some long-term problem?”

“Hi to you too,” I said before I could stop myself.

“We stopped everything to come home from the reception,” she replied, ignoring my sarcasm. I could hear dishes clattering in the background, the muffled murmur of voices. “People were asking where you were, why you hadn’t taken more pictures. We were embarrassed, Lia. Completely blindsided. Why didn’t you tell us something was wrong?”

“Because I didn’t know something was wrong,” I said. “I was standing in line, and everything started to spin, and then I was on the floor.”

“You must have done something to cause it,” she insisted. “Not eating, not sleeping. You know better than that. We taught you better than that.”

I bit down so hard on my tongue I tasted copper. “The doctor said it was a combination of things,” I forced out. “Stress, dehydration, low blood sugar. He said I need to slow down. Maybe see someone about anxiety.”

“Anxiety,” she repeated like it was a foreign word. “Everyone is anxious these days. It’s fashionable.”

“It’s not fashionable if your body literally collapses,” I snapped, my voice rising. “It’s not a trend. I was unconscious, Mom. I scared Rosa half to death. They put me in an ambulance. That’s not some kind of aesthetic.”

On the other end, there was a sharp exhale, almost a scoff. “Watch your tone,” she said.

“Watch my—?” I repeated. “You didn’t even come to the hospital.”

“We were at the reception with important people who came to celebrate you,” she shot back. “It would have been rude to leave. The hospital said it was not life-threatening. You were conscious. Your father and I made a judgment call.”

“You chose not to come,” I said slowly, like I was explaining it to myself as much as to her. “You got a phone call saying your daughter collapsed and your first thought was whether leaving would be rude.”

“Do not twist my words,” she said. “We have raised you, fed you, paid for your education. We have sacrificed for you. One fainting episode does not erase that. Are you trying to make us the villains now?”

I swallowed hard. “I’m not trying to make you anything,” I said. “I’m just telling you how it feels.”

“How it feels,” she repeated, and I could practically see her rolling her eyes. “Feelings are not facts, Lia. The fact is, we had responsibilities. You’re an adult now; you should understand that.”

“I’m an adult,” I echoed. The words hung between us like a challenge.

“Yes,” she said firmly. “Which means we expect you to behave like one. No more episodes. No more drama. You have a job starting in six weeks with a top firm. You will rest, take some vitamins, and then you will get back on track. Do you hear me?”

Something inside me shifted then, a quiet click like a lock turning from the inside.

For years, I’d tried to compress myself into the shape of their expectations. Good daughter. Perfect student. Future business leader. I had measured my worth in GPAs, awards, and bullet points on a résumé that would make them proud.

But lying there in that hospital bed, a flimsy gown tied at the back, a plastic band tight around my wrist, I realized something I’d never let myself admit out loud.

I was exhausted. Not just tired. Not just stressed.

I was done.

“Actually,” I said, surprising even myself, “I don’t think I do hear you.”

A beat of silence. “What did you say?” my mother asked.

“I said I don’t think I hear you,” I repeated, more clearly. “I hear what you want. I hear your expectations. But I don’t think I can do it anymore.”

“Do what?” she demanded.

“Live like this,” I said. My voice trembled, but I didn’t stop. “Push and push until my body literally gives out. Pretend I’m fine because you have guests. Go to a job I don’t even want just so you can say your daughter works at a firm with a fancy name.”

“We discussed this,” she said sharply. “You agreed. You wanted that internship.”

“What I wanted was for you to stop looking at me like I was a disappointment,” I said. The words came faster now, like a dam had broken. “I wanted you to stop comparing me to other people’s kids. I wanted to sit at dinner without hearing about how so-and-so’s son got into medical school or how your coworker’s daughter already makes six figures. You made it very clear what it would take for you to be proud of me. So I tried to give you exactly that.”

“And you succeeded,” she said. “Top of your class. Full-time job. You should be proud of yourself, not complaining.”

“I’m not proud,” I said quietly. “I’m just tired.”

On the other end, I heard her breath catch. For a second, I thought maybe—just maybe—something would crack in her voice, that she’d say something real.

Instead, she said, “You sound ungrateful.”

“Maybe I am,” I replied. “Maybe I’m ungrateful for a life where collapsing in public gets treated like an inconvenience.”

“You are being dramatic and disrespectful,” she snapped. “When you are discharged, come home. We will talk about this face to face. I’m not having this conversation on the phone.”

She hung up before I could answer.

I stared at the blank screen. A buzzing filled my ears, but it wasn’t the machines this time. It was my own heartbeat, loud and insistent.

I didn’t realize my hands were shaking until a tissue appeared in front of my face.

I looked up.

Maria stood in the doorway again, a hesitant look on her face. “I was walking by,” she said softly. “Your door was open. I heard raised voices. I didn’t… I wasn’t trying to eavesdrop, I swear. I just…” She gestured helplessly with the tissue.

“It’s fine,” I said, taking it. My voice cracked on the last word.

“May I come in?” she asked.

I nodded.

She stepped inside and closed the door quietly behind her, as if sealing us into a small bubble of calm.

“I have two sons,” she said without preamble. “One is a straight-A student at a fancy college on the other side of the country. The other dropped out after his first year and is currently trying to figure out what he wants to do, much to his father’s frustration.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I just held the tissue.

“Eight years ago, when my oldest had his high school graduation, I almost missed it,” she went on. “I was at work. I had a deadline, a client breathing down my neck, a boss who thought family events were optional. I kept telling myself I had time. I could leave at the last minute, drive a little fast, it would be fine.”

“What happened?” I asked quietly.

“I got stuck in traffic,” she said. “An accident on the freeway. I sat there in my car, watching the clock, feeling this slow panic crawl up my spine. By the time I finally got to the school, they were stacking chairs. The janitor was sweeping confetti into a corner. My son was gone. I missed the whole thing.”

I winced. “Did he forgive you?”

“Eventually,” she said. “But that’s not why I’m telling you this. I’m telling you because what hurts most, when I think about it, isn’t that I missed the chance to see him in a cap and gown. It’s that I made him feel like he wasn’t worth rearranging my life for.”

She looked at me, eyes bright.

“You are worth rearranging a life for, Lia,” she said. “Even if your parents can’t see that right now.”

A lump rose in my throat. “You don’t even know me,” I repeated again, but this time it came out small.

“I know that you’re a young woman who worked herself so hard she collapsed on a day that was supposed to be a celebration,” she said. “I know you have parents who are more comfortable listing sacrifices than saying I’m sorry or I’m scared for you. I know you’re sitting in a hospital bed wondering if you’re the crazy one for being hurt that they didn’t show up.”

Tears spilled over before I could stop them.

“You are not crazy,” she said firmly. “You are human. And sometimes humans need their parents to come sit by their bed and hold their hand, even if the doctors say it’s not life-threatening.”

My shoulders shook. I tried to wipe my face, but more tears kept coming.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t usually cry in front of strangers.”

“Then it’s a good thing I don’t feel like a stranger anymore,” she said. “May I—?”

She gestured toward my hand. I nodded, and she reached for it, her grip warm and steady.

We sat like that for a while. I cried until my chest felt raw. Maria didn’t offer platitudes or life lessons. She just stayed.

When I finally dried my eyes, she let go of my hand.

“You don’t have to decide anything big tonight,” she said. “Not about jobs, not about your parents, none of it. Right now, your only job is to rest and to listen to your body.”

“My body’s kind of a drama queen,” I said hoarsely.

“Maybe,” she said with a small smile. “Or maybe it’s just louder than your fear for the first time.”

The argument with my mother didn’t end that night. It didn’t really end at all. It went quiet, like embers under ash, waiting for air.

The next day, they discharged me with a follow-up appointment to a cardiologist and a list of referrals for mental health services. Dr. Patel stood at the foot of my bed while Nurse Harris went over the paperwork with me.

“I’m not your therapist,” he said dryly, “but I’m going to give you one piece of unsolicited advice anyway.”

“Is it about drinking more water?” I asked.

“That too,” he said. “But mostly this: your life is not a checklist. You can’t keep treating it like a series of boxes to make other people happy. That kind of living ends one of two ways—burnout or resentment. Sometimes both.”

“I’m already there,” I admitted. “Both, I mean.”

“Then maybe this is your chance to start living differently,” he said. “Take the referrals seriously. Talk to someone. And don’t be afraid to make choices that look selfish from the outside but are kind to your insides.”

“Kind to my insides,” I repeated, amused. “You always talk like that to your patients?”

“Only the ones who try to joke their way out of talking about their feelings,” he said. “Which is most of them.”

After they left, I got dressed slowly, every movement reminding me I wasn’t as strong as I’d been last week. Rosa arrived with a small overnight bag that contained clothes from my apartment, my toothbrush, and a bag of homemade empanadas from her mom.

“You’re coming to my house,” Rosa said. “My mom already changed the guest sheets. She said she wanted to ‘borrow’ you for a few days and that if your mom has an issue, she can call her.”

“I can’t just… move in with you,” I protested weakly. “My stuff is at home. My parents—”

“Your parents didn’t come to this hospital,” she said. “We did. We get first dibs.”

It was said lightly, but there was steel underneath.

“I do have to go home at some point,” I said.

Rosa sighed. “I know. But at least give yourself a couple of days before the big showdown, okay? Come rest. Eat food that wasn’t cooked in a microwave. Watch dumb movies. Then go talk to them when you’re stronger.”

I thought of my mother’s tight voice on the phone. Come home. We will talk about this face to face.

The idea of walking into that house right away made my stomach knot.

“Okay,” I said finally. “A couple of days.”

On the way out, we passed the waiting room again. Maria was there, standing by the vending machines with a paper cup of coffee in her hand. Her son stood beside her, tall and lanky, leaning on a pair of crutches, his ankle wrapped.

When she saw me, her face lit up. “Hey, look at you,” she said. “Standing on your own two feet.”

“Mostly on my own,” I said, gesturing at Rosa, who was practically glued to my side.

“Good,” she said. “Everybody needs a Rosa.”

“This is my mom behavior in action,” Rosa said to her, grinning. “Hi, I’m Rosa. Thank you for sitting with Lia yesterday. She told me.”

“Just doing what I wish someone had done for my boy years ago,” Maria said. “Hi, I’m Maria. This is my son, Nico.”

“Nice to meet you,” he said, raising a hand.

We exchanged a few more polite words, then the nurse at the front desk called Maria over to sign discharge papers.

As she turned to go, she looked back at me. “Hey, Lia?” she said.

“Yeah?”

“You have my number,” she said.

I blinked. She must have put it in my phone at some point while I was half asleep.

“If you ever need another mom pep talk,” she added, “or a neutral adult who doesn’t know your entire childhood but understands the general chaos of it, call me. Or text me. Or send smoke signals. I mean it.”

For a second, emotion rose up in my throat again. But this time, the tears didn’t come. Instead, my chest felt… fuller. Stronger.

“Thank you,” I said. “For everything.”

She nodded once, like we’d just sealed a quiet agreement.

As Rosa drove us away from the hospital, sunlight flooded through the windshield. The city moved around us like nothing had happened: people walking dogs, delivery trucks double-parked, kids on scooters. Life, continuing.

Inside the car, though, something had shifted.

“Do you ever feel like you’re breaking a rule by putting yourself first?” I asked suddenly.

“All the time,” Rosa said. “I was raised Catholic, remember? We’re basically programmed to feel guilty for existing.”

I snorted.

“But you know what I realized?” she continued. “There’s a huge difference between being selfish and having a self. You’ve spent your whole life making sure everyone else is okay with your choices. Maybe it’s time to make sure you are.”

“What if my parents never accept that?” I asked.

She drummed her fingers on the steering wheel. “Then you’ll still be alive, and you’ll still be you,” she said. “And maybe, one day, they’ll change. Or maybe they won’t. But you can’t put your life on pause while you wait to find out.”

The “couple of days” at Rosa’s house turned into a week.

Her mom fussed over me like I was an extra daughter, filling my plate with food and shaking her head when I tried to help with dishes.

“You can help when your face doesn’t look like it lost a fight with finals week,” she said.

At first, I felt guilty. Guilty for not being home. Guilty for resting when there were emails I could be answering, future projects I could be planning.

But every time my chest tightened, every time my mind raced, I remembered the floor of the gym, the blinding lights, Ben’s calm voice in my ear.

Your body will make decisions for you when your mouth is too scared to say the words.

One afternoon, I carved out an hour and called the counseling center from the referral list. The soonest appointment was in two weeks, but I took it. Just putting it on the calendar felt like planting a small flag in new territory.

My parents called every day but one. The conversations followed the same pattern: my mother demanded updates, my father asked brief, practical questions about tests and results, and then they circled back to logistics.

“When are you coming home?”

“What did the doctor say about work?”

“This company expects reliability, you know that.”

The longer I stayed away, the more tension I heard in their voices. I could picture my mother pacing in the kitchen, my father sitting at the table, silent but present, the way he always was in our arguments—there, but not really part of the emotional storm.

Finally, at the end of the week, I knew I couldn’t delay it any longer.

“I’m coming home tomorrow,” I told my mother on the phone.

“Good,” she said immediately. “We need to have a serious conversation about what happens next.”

“Yeah,” I said. “We really do.”

Walking up the front path to my parents’ house felt like walking onto a stage where I already knew my lines but hated the script.

The lawn was trimmed, the flower beds neat. The porch light was on even though it was still early evening, a warm glow that had once made me feel safe when I came home from school.

Now, it just made my stomach tighten.

Rosa squeezed my hand before I got out of the car. “Text me if it turns into a whole thing,” she said. “Say ‘pineapple’ if you need an extraction.”

“Why pineapple?” I asked, half laughing.

“Because it’s funny,” she said. “And because you would never casually text me that otherwise.”

“Fair,” I said.

I stood on the porch for a full thirty seconds before knocking, even though I had a key. I needed the tiny buffer, the line of formality.

My mother opened the door almost immediately, like she’d been waiting right behind it.

She looked put together, as always: hair styled, lipstick on, earrings matching her blouse. The only sign anything was off was the faint tightness around her eyes.

“You look pale,” she said by way of greeting. “And thinner.”

“Hi, Mom,” I said.

She stepped aside. “Come in. Your father is in the dining room. We’ve been waiting.”

It sounded like an evaluation, not a welcome.

I followed her down the hallway, past framed photos of our family: me in braces, me at piano recitals, me with trophies that felt almost heavier now. All of them versions of me trying so hard.

My father sat at the dining table, a glass of water in front of him. He wore his work clothes still, sleeves rolled up, tie loosened.

“Hi, Dad,” I said softly.

He stood up awkwardly, like he wasn’t sure whether to hug me. After a brief hesitation, he patted my shoulder once and sat back down.

“You gave us quite a scare,” he said.

I blinked. “I did?”

“Yes,” he said. “Hearing that you collapsed in front of hundreds of people. That’s not nothing.”

“You could have come,” I said, the words out before I could swallow them.

He looked away. “The hospital said you were stable,” he murmured. “Your mother already explained.”

My mother took her seat across from him and folded her hands on the table.

“Sit,” she said. “We need to talk.”

I sat at the end of the table, halfway between them.

They looked at me like a panel facing a candidate.

“We are glad you are home,” my mother began. “But this situation is not something we can just ignore. The way you spoke to me on the phone was unacceptable.”

“The way you talked to me on the phone was unacceptable,” I said before I could stop myself.

She stiffened. “Excuse me?”

“You called me ungrateful for being scared and hurt,” I said, my voice shaking but steady enough. “You told me not to ‘cause drama’ when I literally passed out in front of everyone I know. You made it about your embarrassment and your guests, not about my health.”

“We have every right to be upset,” she said. “We spent years investing in you. You had everything lined up—honors, a job offer, a clear path. And then, in one day, you create this chaos that makes people question whether you can handle pressure. Do you have any idea what this looks like?”

I stared at her. “I almost ended up back in the hospital listening to you talk about optics,” I said. “Do you have any idea what that feels like?”

My father cleared his throat. “Let’s everyone calm down,” he said. “We’re all coming at this from different perspectives.”

My mother shot him a look like whose side are you on?, then turned back to me.

“What, exactly, do you want from us, Lia?” she demanded. “Because from where I’m sitting, it sounds like you’re blaming us for your choices.”

“I’m not blaming you for everything,” I said. “But I am saying your expectations are part of what pushed me to this point. I’ve been chasing your version of success since I was old enough to count. I never stopped to ask myself if it’s what I actually want.”

“And now?” my father asked quietly.

“Now I know it’s not,” I said. Saying it out loud felt like stepping off a cliff—and realizing there might be a bridge just out of sight. “I don’t want to start that job in six weeks.”

Silence slammed into the room.

My mother’s eyes widened. “You have an offer from one of the top firms in the city,” she said slowly, as if I’d forgotten. “Do you know how many people would kill for that opportunity?”

“I know,” I said. “And maybe one of them should have it. Someone who actually dreams of doing what they do. I never did. I picked that path because it sounded like the right answer whenever anyone asked, ‘So what are you doing after graduation?’ It made you happy. It impressed your friends. But it never felt right to me.”

My father rubbed his temples. “So what would you rather do?” he asked. “Because if this is just ‘I don’t want to work’—”

“That’s not what I’m saying,” I cut in. “I’m saying I want time to figure it out. I want to work, but at something that doesn’t make my heart race in the wrong way. I’ve thought about nonprofit work. Maybe something with education, or community programs. I’ve thought about grad school in a different field entirely. But I can’t even hear my own thoughts clearly when all I hear outside is, ‘Don’t waste your potential’ and ‘Don’t embarrass us.’”

My mother scoffed. “You sound very naive,” she said. “This is not how the real world works. You don’t just… wander around doing what feels good. You take opportunities when they come. You secure your future.”

“I took all the opportunities you told me to take,” I said. “And my body hit the brakes for me.”

Her lips pressed together. “Are you really going to keep throwing that in our faces?” she asked. “People faint. People get overwhelmed. It happens. It doesn’t mean you throw your whole life plan away.”

“Maybe it means the life plan needs revisiting,” I said. “Maybe it means I stop pretending I’m okay with everything just to keep the peace.”

“You’re being selfish,” she said flatly.

There it was. The word I’d been bracing for.

I took a deep breath. Maria’s voice echoed in my head: There’s a difference between being selfish and having a self.

“Maybe,” I said quietly. “Or maybe I’m finally having a self. Either way, I’m not going back to the way things were.”

My father looked between us, exasperation etched into his features. “We cannot support you if you just throw away a stable career path,” he said. “We paid for your education with the expectation that you would use it. We are not going to fund you ‘finding yourself’ while you drift around trying hobbies.”

“I’m not asking you to,” I said quickly. “I’ll get a job. It may not be glamorous, but I’ll pay my own bills. Maybe I’ll live with roommates, maybe I’ll stay with Rosa’s family until I can save up. I’m not asking you for money. I’m asking you to accept that this is my choice.”

My mother’s eyes flashed. “So that’s it?” she said. “You’re just going to walk away from everything we planned?”

I swallowed. “I’m walking toward something,” I said. “I just don’t know exactly what it is yet. That’s scary enough without you making me feel like I’m betraying you on top of it.”

“We didn’t raise you to be this irresponsible,” she shot back.

“No,” I said. “You raised me to be responsible at any cost. Even if the cost was me.”

The room went very still.

My father looked like he’d been struck. My mother stared at me, mouth slightly open, and for the first time, I saw something besides anger flicker across her face.

Fear.

“You really think… we don’t care about you?” she asked, voice quieter.

“I think you care about the version of me that fits the story you wanted to tell,” I said. “I think you care about not wasting the sacrifices you made. I think you care about not being judged by your friends or family. But when I was lying in that hospital bed, alone, the people who showed up for me were Rosa… and a stranger whose son had a sprained ankle. You stayed at a reception.”

“That’s not fair,” she whispered.

“It’s honest,” I replied.

We sat there, the three of us, suspended in a moment that felt like it could tip either way.

Finally, my father spoke.

“I don’t know how to do this,” he said slowly. “When we were your age, we didn’t have choices. We took jobs, we worked, we saved. We didn’t talk about feelings. We just… survived. We pushed you to aim higher because we didn’t want you to struggle like we did.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m grateful for that. I really am. But I don’t want to spend my life just surviving, Dad. I want to actually live it. And that means I have to make some of my own choices, even if they scare you. Even if they disappoint you.”

My mother swallowed. “And if we say we can’t support those choices?” she asked.

“Then I’ll still make them,” I said. “But I’ll miss you. Every day.”

Tears shimmered in her eyes, but she blinked them back quickly, like she was ashamed to let them fall.

“We need time to think,” she said. “Your father and I need to discuss this.”

“I figured,” I said, standing up. My legs trembled, but I stayed upright. “I’m going to stay at Rosa’s a little longer while I look at other options. I’ll send the offer letter to the firm and let them know I’m withdrawing.”

“You’re going to regret this,” my mother said.

“Maybe,” I said honestly. “Or maybe I’ll regret it more if I don’t try.”

I walked to the front door, feeling their eyes on my back the whole way. My hand shook as I reached for the knob.

Just before I opened it, my father’s voice called out.

“Lia.”

I turned.

He stood in the hallway, hands shoved in his pockets.

“For what it’s worth,” he said, “I’m… proud you’re thinking for yourself. Even if I don’t understand it yet.”

My throat tightened. “Thank you,” I whispered.

My mother said nothing. But she didn’t tell him to take it back.

It wasn’t a perfect ending. It wasn’t a movie moment where everyone hugged and cried and everything was suddenly fixed.

But it was something.

In the weeks that followed, my life didn’t magically snap into place.

I withdrew my acceptance from the firm. The recruiter’s email was curt but professional. We are disappointed you’ve chosen this path, but we wish you the best. I stared at the words for a long time.

I got a part-time job at a local community center helping with after-school programs and weekend events. It paid less than minimum wage at first, but it was something. I helped kids with homework, played basketball badly, learned how to referee arguments over board games.

On my first day, a tiny girl with pigtails took my hand and said, “Are you coming back tomorrow?” like it was the most important question in the world.

“Yes,” I said without hesitation. “Yes, I am.”

I started therapy. The first session felt awkward; I was hyper-aware of every word I said, as if I were being scored. But slowly, I began to peel back layers of expectations and fear. I said things out loud I’d only dared to think in the quietest parts of my mind.

My therapist, a woman about my mother’s age with kind eyes and a no-nonsense tone, gave me tools to recognize when my body was sounding alarms. She helped me name anxiety, not as a moral failure but as a signal.

Sometimes, I still woke up in the middle of the night with my heart racing, convinced I’d made a terrible mistake turning down that job. Other times, I walked past office buildings downtown and felt a pang of longing for the simple clarity of a paycheck and a business card with a logo people recognized.

And my parents? We were… complicated.

My mother didn’t call for three days after I withdrew the offer. When she finally did, it was to ask if I’d remembered to send a thank-you card to my scholarship donor.

But over time, the conversations changed.

One night, weeks later, she called and didn’t mention work at all. Instead, she asked, “What do you do at this community center, exactly?”

I told her about the reading program, about the kids who’d never had someone sit with them patiently while they stumbled over new words. I told her about a teen who’d lit up when we started a photography club using donated cameras.

“That sounds…nice,” she said slowly. “Nice” was not a word she usually applied to jobs.

“It is,” I said. “I like feeling like I can help someone directly.”

We argued again, of course. Old patterns don’t vanish overnight. She still worried I was wasting my degree. I still bristled when she compared me to someone else’s child.

But once, when I mentioned an upcoming cardiology appointment, she said, very softly, “Do you want me to go with you?”

I hesitated, then said, “Yeah. I think I do.”

She sat beside me in the waiting room, hands folded tightly in her lap. We didn’t say much, but when they called my name, she stood up with me.

Walking into that exam room, I remembered collapsing on the graduation stage. I remembered Ben’s calm voice, the ambulance ceiling, the cold of the ER.

I also remembered Maria’s hand in mine, Rosa’s fierce loyalty, Dr. Patel’s gentle reminder that my life was not a checklist.

I remembered my own voice at my parents’ dining table, trembling but clear.

I don’t want to live like this anymore.

The doctor said my heart was fine. Some minor rhythm quirks, nothing dangerous, manageable with awareness and care.

Afterward, Mom and I walked to the parking lot together.

“I’ve been thinking,” she said quietly as we reached the car. “About what you said. About not wanting to just survive.”

I looked at her, waiting.

“Your father and I… we don’t know how to help you with that,” she admitted. “We only know survival. But we’re… trying. I’m trying.”

The admission cracked something open in me.

“I know,” I said. “And I’m trying too.”

We stood there in awkward silence for a moment, then she reached out and adjusted the collar of my jacket like she had when I was ten.

“You should drink more water,” she muttered.

“I know,” I said, smiling a little. “Everyone keeps saying that.”

Months later, on a rainy Tuesday when the community center was quieter than usual, I sat in my tiny office between stacks of art supplies and bins of sports equipment.

My phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number.

Unknown: Is this Lia from the hospital?

Unknown: It’s Maria. Hospital stranger / emergency room cardigan lady.

My heart leaped.

Me: Hi!! Yes, it’s me. How are you and Nico?

Maria: We’re good. His ankle is fully recovered. He’s back to playing pickup soccer and ignoring his mother’s advice.

Maria: I was just thinking about you and wanted to check in. How’s your heart? (In every meaning of the word.)

I stared at the question, then looked around my little office. At the crayon drawings pinned to the wall, at the schedule of programs I’d helped plan, at the slowly growing plant Rosa had given me as a “new life” present.

My heart beat steady and strong in my chest.

Me: My heart is okay. Still a work in progress. But beating in the right direction, I think.

Maria: That’s all any of us can ask for.

Maria: Proud of you, kid.

Proud of you.

Three words I’d spent twenty-two years chasing from the wrong directions.

I smiled at the screen, then at the stack of handouts on my desk for a new mentoring program I was helping launch.

When I collapsed at my graduation, I thought it was the worst thing that could have happened. The day my carefully constructed future crumbled, the moment I proved, once and for all, that I was too weak for the path laid out for me.

But it turned out to be something else, too.

It was a pause. A forced breath. A crack in the script big enough to step through.

It was the moment I realized that being abandoned in one waiting room didn’t mean I was alone forever. Sometimes, the people who held your hand weren’t the ones who shared your last name. Sometimes, family showed up in borrowed cardigans and bright yellow dresses and late-night phone calls that began with “You okay?” instead of “What did you do?”

Most of all, it was the beginning of a life where my worth wasn’t measured in the lines of a résumé, or the approval sitting across a dining table, but in the quiet, steady beat of my own heart—finally allowed to set the pace.

THE END

News

BEHIND THE LIGHTS & CAMERAS: Why Talk of a Maddow–Scarborough–Brzezinski Rift Is Sweeping MSNBC — And What’s Really Fueling the Tension Viewers Think They See

BEHIND THE LIGHTS & CAMERAS: Why Talk of a Maddow–Scarborough–Brzezinski Rift Is Sweeping MSNBC — And What’s Really Fueling the…

TEARS, LAUGHTER & ONE BIG PROMISE: How Lawrence O’Donnell Became Emotional During MSNBC’s Playful “Welcome Baby” Tradition With Rachel Maddow — And Why His Whisper Left the Room Silent

TEARS, LAUGHTER & ONE BIG PROMISE: How Lawrence O’Donnell Became Emotional During MSNBC’s Playful “Welcome Baby” Tradition With Rachel Maddow…

🔥 A Seasoned Voice With a New Mission: Why Rachel Maddow’s “Burn Order” Is the Boldest Move MS Now Has Made in Years — and the Hidden Forces That Pushed It to the Front of the Line 🔥

🔥 A Seasoned Voice With a New Mission: Why Rachel Maddow’s “Burn Order” Is the Boldest Move MS Now Has…

They Mocked the Plus-Size Bridesmaid Who Dared to Dance at Her Best Friend’s Wedding—Until a Single Dad Crossed the Room and Changed the Whole Night’s Story

They Mocked the Plus-Size Bridesmaid Who Dared to Dance at Her Best Friend’s Wedding—Until a Single Dad Crossed the Room…

The Night a Single Dad CEO Stopped for a Freezing Homeless Girl Because His Little Daughter Begged Him, and the Unexpected Reunion Years Later That Changed His Life Forever

The Night a Single Dad CEO Stopped for a Freezing Homeless Girl Because His Little Daughter Begged Him, and the…

The Young White CEO Who Refused to Shake an Elderly Black Investor’s Hand at Her Launch Party—Only to Be Knocking on His Door Begging the Very Next Morning

The Young White CEO Who Refused to Shake an Elderly Black Investor’s Hand at Her Launch Party—Only to Be Knocking…

End of content

No more pages to load