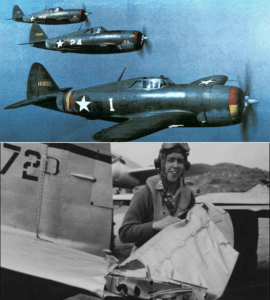

Engineers Scoffed That the P-47 Thunderbolt Was Too Fat, Too Slow, and Too Heavy to Dogfight—Then Its Pilots Turned It Into a Diving Monster That Crushed 3,752 Luftwaffe Fighters and Saved Countless Crews

The first thing Lieutenant Sam Carter heard about the P-47 Thunderbolt was that it was a joke.

He was standing on the edge of the hardstand in muddy English drizzle, flight jacket zipped to his chin, watching a ground crewman taxi the big radial-engined brute past the dispersal hut. The airplane looked less like a sleek fighter and more like someone had bolted wings to a beer barrel.

Beside him, his roommate, Eddie “Tex” Malloy, whistled low.

“Good grief,” Tex said. “They shipping us to the front or the county fair? That thing looks like it should have a merry-go-round pole through the middle.”

One of the engineers from Republic Aviation, in a crisp coat that hadn’t yet learned what oil stains were, overheard and smirked.

“You boys wanted something that could do it all,” the engineer said. “High altitude, long range, carry weight, take abuse. That’s what does it.”

Tex shook his head. “That thing’s too heavy to dogfight,” he said. “Put that up against a Messerschmitt and the only way we win is if he dies laughing.”

The engineer shrugged. “Design says it can dive like a stone and climb like a home-sick angel once it’s going,” he said. “You don’t fight in circles in this. You fight vertical.”

Sam didn’t say anything. He just watched the Thunderbolt rumble by, props chopping the mist into swirling vortices. The pilot sitting high in the cockpit raised a gloved hand in a lazy salute.

The airplane’s nose art—a freshly painted cartoon jug with wings—grinned back at them.

“Jug,” Tex said. “Fits.”

The nickname stuck quicker than the official name ever did.

The P-47 was not Sam’s first fighter.

Back in the States, he’d trained on lighter, more graceful machines. The P-40 had been his first love—sleek, shark-mouthed, with a nose that pointed exactly where your heart did. It wasn’t perfect, but it looked like what a fighter pilot imagined when he closed his eyes.

The first time he climbed the ladder into a Thunderbolt, his hands hesitated on the rungs.

Up close, the engine looked absurd—an eighteen-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2800, all plumbing and fins and mass. The propeller blades were broad and heavy, like paddles. The wings were thick, built to hold fuel and ammunition and still bring you home when someone took a bite out of them.

He settled into the cockpit and immediately felt small. The nose ahead of him stretched long; the canopy framing was sturdy, not delicate. The panel was full of gauges, more than he was used to. There were extra levers, extra switches—turbo-supercharger controls, intercooler, more complication.

The crew chief, a stocky sergeant named Russo with a permanent smear of grease along his jaw, leaned against the side and peered in.

“Like it?” Russo asked.

Sam tried to decide.

“It’s… big,” he said.

Russo grinned. “So’s a bull,” he said. “Doesn’t mean you want to be in front of it when it gets moving.”

Sam looked around the cockpit again.

“What do you think of it?” he asked.

Russo patted the fuselage fondly. “She’s ugly, loud, and drinks fuel like a sailor,” he said. “But she’ll bring you home with half a wing and holes you could crawl through. And she dives like nothing I’ve ever seen. Just don’t try to dance with it.”

“Dance?” Sam asked.

Russo held his hands up, mimicking an airplane rolling and turning.

“You try to twist and twirl on the same level as those little German jobs,” Russo said, “you’ll feel like you’re moving through syrup while they skate around you. This thing’s about momentum. Use it right, you’ll love her. Use it wrong…”

He shrugged.

“Well,” he said. “We’ll patch what’s left.”

Engineers back at Wright Field, safe behind drafting boards and calculations, called the P-47 “multi-role.” They wrote memos about airframes, load factors, compressibility limits. On the line, the pilots distilled all of that into one blunt opinion:

“It’s too heavy to dogfight.”

First combat tour, Sam got to see how that opinion formed.

They’d been flying top cover for a formation of B-17s, their squadron strung out in a high, loose weave above the big bombers. The mission card said “escort,” but in practice that meant “stay high, shout warnings, and try not to get bounced yourselves.”

It was a bright day over France, the sky full of contrails and the faint, blurry flashes of flak in the distance.

“Bandits, three o’clock high!” the controller’s voice crackled over the radio, almost bored.

Sam craned his neck.

Dark specks were coming in out of the sun, sliding down like beads on invisible wires. Bf 109s and Fw 190s—thin-winged, angular, purpose-built.

“Blue Flight, break!” Major Collins, their squadron leader, barked.

Sam rolled his Jug into a turn, hauling back on the stick, feeling the weight of the airplane resist him. The Thunderbolt tightened its turn, but not as fast as his training reflexes wanted. The G-forces piled on, pressing him into the seat.

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Tex’s airplane trying to follow. The Jug’s wings bit into the air, but the German fighter dropping toward them from above seemed to pivot like it was weightless, sliding inside their turn with predatory ease.

“Can’t hold him off—” Tex grunted, the strain in his voice transmitting as clearly as the words.

Sam mashed the throttle, but at that altitude, with that load, the P-47 didn’t leap the way the P-40 had. It lumbered, then gathered itself, then began to claw upward.

The 109, lighter and already with speed, slid into firing position on Tex’s tail.

“Tex, break down!” Sam shouted.

Tex rolled inverted and dropped, but the German pilot anticipated the move, following him down in a spiraling dive. Tracers flashed between them, then through Tex’s machine.

“Hit—hit—” Tex’s voice cracked. “I’m on fir—”

It cut off.

Sam swallowed once, hard, and forced himself not to stare at the trail of smoke spiraling down.

He dove, trying to catch the attacker as it pulled out, but the German had already used his advantage and left. He zoomed back up to altitude, a sharp, climbing arc that the heavy Thunderbolt struggled to match.

By the time Sam reached where the fight had been, there was nothing but air and smoke.

Back at Debden, in the debriefing hut that smelled of sweat, coffee, and wet wool, the opinion solidified.

“We can’t turn with them,” one pilot said bitterly. “They dance around us, pick what they want, and leave.”

“We’re flying dump trucks,” another muttered. “Jeez. Are they trying to get us killed with this beast?”

Major Collins let them vent, arms folded, jaw tight.

When the grumbling subsided a bit, he slapped the board with a stick.

“Enough,” he said. “You’re right about one thing: you can’t fight this bird the way you fought P-40s. This isn’t a knife fighter. It’s a sledgehammer. Stop trying to fence with it.”

He pointed to a sketch he’d drawn—two lines, one coming down, one going up.

“You see them high? You don’t meet them on the same level and play ring-around-the-rosie,” Collins said. “You go higher. You get sun. You get speed. Then you drop. One pass. One burst. Then you keep going and climb. You don’t stick around to see how it turned out until you’re ready for another run.”

“Boom-and-zoom,” someone said skeptically.

“Exactly,” Collins said. “You’re thinking like you’re flying a featherweight. You’re not. You’ve got eight .50s and a turbocharged supercharger that will still shove air at this engine when those little 109s are gasping. Use that.”

He tapped the sketch again.

“And for heaven’s sake,” he said, “stop saying ‘too heavy to dogfight.’ You’re not supposed to dogfight. You’re supposed to break bones and leave.”

Sam sat there, hearing the words, feeling the gap between how he’d been flying and how he needed to fly.

He thought of Tex’s Jug tumbling, fire licking out of the cowling.

He didn’t want to repeat that lesson.

He went back to his dispersal hut that evening and pulled out his notebook. On the front, he wrote in block letters:

FIGHT YOUR AIRPLANE, NOT YOUR MEMORY.

Underneath, he listed what the Thunderbolt did well.

High-altitude performance.

Dive speed.

Ruggedness.

Firepower.

He underlined each word.

“Too heavy to dogfight” wasn’t the flaw.

It was the point.

The first time he really trusted the Jug was over Germany, escorting bombers to a ball-bearing plant that intelligence officers kept calling “vital” with a seriousness that hinted they’d be in trouble if it wasn’t.

They climbed for what felt like forever, the Thunderbolt’s engine rumbling steadily, turbocharger whirring as it shoved dense, cold air into the cylinders. The altimeter crept up past twenty thousand, then twenty-five.

By thirty thousand, the world below looked like a map. The bombers hung a little lower than them, silver beads in a long, shimmering string.

“Eagle Lead from Control,” the controller’s voice came. “Bandits assembling, ten o’clock high, distance twenty.”

“Copy, Control,” Major Collins replied. “Blue Flight, with me. Red Flight, stay high cover. Yellow, watch the tail.”

Sam, in Blue Two, glanced up and ahead.

Black dots crawled at the edge of sight, organizing themselves into something more dangerous.

“Let’s take it upstairs,” Collins said. “We’ll come down our way this time.”

They climbed.

The Thunderbolt felt more at home up here than any airplane Sam had flown. The engine still had power to spare. The wings, thick though they were, bit cleanly into the thin air.

Thirty-five thousand.

The Luftwaffe fighters were now slightly below and ahead, starting their glide into the bombers.

“Blue Flight, roll,” Collins said. “We’re going to drop some presents.”

Sam rolled his Jug onto its back and pushed the nose down.

Gravity, plus a whole lot of Pratt & Whitney, took over.

The noise in the cockpit changed. Air rushed louder against the canopy. The Mach meter’s needle crept up. The controls stiffened as compressibility—the new word everyone was muttering about—nibbled at the edges of command.

Out of habit, Sam reached for the trim tabs, adjusting, keeping the stick where he wanted it.

The airspeed indicator’s needle wrapped itself around numbers that would have made a P-40 shudder and shed parts.

The P-47, dense and solid, loved it.

Below him, the German formation swelled from dots to shapes—wings, fuselages, crosses.

“Pick one and stay with him,” Collins’ voice crackled. “Short burst. Don’t get greedy.”

Sam chose a Messerschmitt that was sliding slightly away from the main group, lining up on the left flank of the bomber box.

He adjusted his lead, aiming not where the plane was, but where it would be when his cascade of .50s crossed its path.

His thumb found the trigger.

For a second, the cockpit shook as all eight guns spat flame and brass. The smell of cordite flooded in, familiar and oddly comforting.

He saw his tracers walk through the 109’s right wing root and canopy in a clean, savage line.

The German fighter flinched, rolled, then dropped away trailing smoke.

Sam didn’t watch it fall. He pulled slightly, letting the Jug’s tremendous speed carry him down and out under the German formation.

There was a moment—just a heartbeat—when he was the lowest airplane in that sky, bombers above, German fighters turning to look, gravity still dragging him earthward.

Then he eased back, felt the air thicken under his wings, felt the engine’s surge as he regained vertical space.

The climb was slower than the dive, but he had momentum. The Jug, heavy as it was, translated that speed into altitude like it was cashing in stolen chips.

“There you go, Blue Two,” Collins called. “That’s the way.”

Sam leveled off above the fight again, heart pounding, breath clouding the inside of his oxygen mask.

He’d been the hammer that time, not the nail.

Compared to that first messy, turning engagement over France, this felt… almost clean.

They did it again. And again.

Sometimes the Germans managed to twist up enough to drag them into flatter fights, where the Thunderbolt’s bulk hindered more than helped. On those days, things got ugly. Men didn’t come back. The “too heavy” whispers returned.

But gradually, a new reputation layered itself over the old worries.

B-17 crews, looking up from bombardier sights or out from waist windows, saw big, chunky silhouettes dropping from the sun, ripping through attackers, and then clawing back up.

“Those Jugs can move,” one gunner said in a debrief. “They drop like anvils and go back up like they’re hooked to a winch. I like seeing them around.”

Somewhere, someone wrote that down.

Sam started keeping his own tally.

Not of “victories”—he never got comfortable with that word—but of missions where the P-47’s supposed flaws turned out to be its strengths.

The day they limped home with a cylinder shot out and oil pressure dropping, and the engine still ran long enough to get them back over friendly fields.

The time his wingman, Roberts, took flak to one wing that would have snapped a more fragile fighter in half, and the Jug held, bent but together.

The afternoon they drew the short straw and got tasked to hit a rail yard instead of escorting bombers.

They’d loaded the Thunderbolts with bombs under the wings and belly tanks that would be dropped along the way. The airplane, already hefty, now felt downright gluttonous.

“You sure we’re still fighters?” Roberts had grumbled. “Feels like we’re borrowing a job from the heavies.”

“Trust me,” Collins had said. “Those eight fifties don’t care what you call yourself.”

They came in low that day, too low for anyone’s comfort.

Tracers reached up. Light flak pocked the air. The P-47s roared in over the yard, the Jugs’ radial engines howling.

Bombs fell, tearing up tracks and boxcars.

And then, as they pulled up, those eight guns spoke.

Sam raked a line of freight cars with .50-caliber fire, seeing wood and metal burst apart in a spray of splinters. Another pilot stitched a row of locomotives, sending one boiler bursting sideways.

When they broke away, the rail yard was a mess.

“Too heavy to dogfight,” Roberts said over the radio, breathing hard. “But just about perfect for this.”

They were still there to escort bombers, to tangle with fighters when needed. But more and more, in the margin notes and mission cards, other words appeared next to the P-47’s designation.

“Ftr-bomber.”

“JABO.” Jagdbomber, the Germans called it, not as a compliment at first.

The pilots adopted it anyway. It sounded like something that punched back.

The war stretched on.

Sam flew more missions than he ever thought one person could, each one blurring into the next, except for the moments that didn’t.

The cloud you could walk on at twenty thousand feet.

The sudden, hateful red flower of a bomber exploding in midair.

The eerie beauty of contrails crisscrossing a blue sky, turned into a shape you might have admired on a peaceful day.

And always, the P-47 under him, loud and solid.

The engineers kept tinkering as the months dragged by.

They gave the Jug a bubble canopy, taking away the old razorback spine and giving pilots a clear, almost panoramic view. Sam loved it; he no longer had to crane his neck as far to check his six.

They bolted on bigger, paddle-blade propellers to better harness the engine’s power. They tweaked the turbo system, refined cooling, added hardpoints.

“Look at that,” Tex would have said, if he’d been there. “They put the Jug on a diet by feeding it more.”

Tex wasn’t there to say it. A lot of men weren’t.

That was the part no engineer’s chart captured: the quiet subtraction of names from the list.

Sam carried those in a different ledger.

One gray afternoon, between missions, he walked past Operations and saw an intelligence officer pinning a fresh chart to the briefing board.

It was a simple line graph, but the heading caught his eye:

ENEMY AIRCRAFT DESTROYED BY ALLIED FIGHTERS IN ETO – BY TYPE

Underneath, colored lines traced upward at different angles. P-51, P-38, P-47. RAF types. Each had a number at the end.

A few pilots clustered around, murmuring.

“Look at that,” one said. “Those Mustangs really racked ’em up once they came in.”

“Yeah,” another replied. “But check the Jug’s line.”

Sam stepped closer.

On the right edge, next to the P-47’s color, a handwritten note:

3,752

“Is that…?” someone started.

“Air-to-air claims in this theater,” the intel officer said. “All Thunderbolt units combined. As of last month.”

“Three thousand seven hundred fifty-two?” a young pilot repeated, disbelieving. “In this ‘too-heavy’ thing?”

The intel officer shrugged.

“Too heavy to dogfight if you try to turn it like a Spit,” he said. “Just heavy enough to drop out of the sun like a brick and turn fighters into confetti on the way. It’s not the prettiest, but it’s done work.”

One of the newer arrivals, fresh from stateside training, whistled.

“I heard engineers back home calling it a flying milk bottle,” he said. “You think they’ve seen this?” He tapped the number.

“Engineers see numbers before we do,” the intel officer said dryly. “Trust me. They’re arguing right now about what it means.”

Sam looked at the figure, then at the thick, rising line.

3,752.

It wasn’t a single story. It was thousands.

Some of those were his. Most weren’t. All of them were a little piece of airspace somewhere over Europe where a Thunderbolt pilot, sitting behind all that metal and noise, had done what the airplane was built to do.

“Too heavy to dogfight,” Sam murmured.

Collins, passing by with a cup of coffee, heard him and snorted.

“Too heavy for some dogfights,” the major said. “Just right for the kind we decided to fight.”

He nodded at the chart.

“See that number?” he said. “That’s engineers being wrong in the right direction.”

Sam flew his last combat mission in a Jug on a day that smelled like wet soil and spring, even from twenty thousand feet.

The war in Europe was nearing its end. Everyone could feel it—like a storm that had passed but still growled on the horizon.

The Luftwaffe, once a constant, ferocious presence, now came up only in fits and starts. Fuel was scarce. Pilots were scarce. The ones that did appear were often either very young or very desperate.

The mission was supposed to be a routine sweep—“armed reconnaissance,” the briefing card said, as if that made driving into danger sound tidy.

They’d take their P-47s across the Rhine, range ahead of the ground forces, and hit targets of opportunity—trucks, rail cars, maybe an airfield if they got lucky.

The Thunderbolt was in its element.

They roared in low, engines thunderous, eight-gun wings reaching out.

Sam dropped his belly tank over a patch of woods, feeling the Jug lighten. He rolled in on a column of vehicles, released his bombs, watched the near end of the road blossom into craters.

Then he pulled up and squeezed the trigger, stitches of tracer walking along a row of trucks. Canvas tops shredded, vehicles slewed sideways.

“Too heavy to dogfight,” Roberts said over the radio, whooping. “But these boys aren’t fighting back in the air, are they?”

“Stay sharp,” Collins cautioned. “Flak’s still real. So’s small arms. Don’t get cocky.”

Sam took a breath, steadying. He did one more pass, then pulled up to rejoin the squadron.

Above them, the sky was strangely empty.

No contrails. No neat boxes of bombers. No dark specks rising to meet them.

Just pale blue and a few wisps of cloud.

“See much when you were a rookie?” Roberts asked later, at the bar in the battered officers’ club.

“Too much,” Sam said.

“You think they’ll remember the Jug?” Roberts asked. “Thirty years from now, when they’re all flying rocket ships, or whatever engineers dream about next?”

Sam took a sip of beer, the glass cool in his hand.

“Maybe,” he said. “Maybe they’ll remember it as the airplane everyone thought was too heavy, too clumsy, too late… and then had to rewrite the charts for.”

He thought about all the times he’d cursed the Thunderbolt’s weight in a tight turn. And all the times he’d blessed it when flak hit and the airplane just shrugged and kept flying.

“I think,” he added slowly, “they’ll remember it as the fighter that did the ugly, important work. The one that showed up anyway.”

After the war, Sam went home.

The fields looked smaller. The sky did not.

He took a job flying crop dusters for a while, then small transports. Nothing with a turbocharger. Nothing with guns.

He kept a photograph on his study wall—his squadron lined up in front of a row of P-47s, bubble canopies catching the light, noses painted with teeth and ladies and lucky charms.

Visitors would sometimes point.

“Must’ve been something, flying those,” they’d say.

“They were loud,” Sam would reply with a half-smile. “And heavy. And just about perfect for what we had to do.”

Years later, when an aviation magazine published a retrospective on World War II fighters, they asked him for a quote.

The article, written by someone who’d grown up after the war, opened with all the old complaints—too heavy, too slow to climb, too big to turn with the svelte fighters.

Then it listed the 3,752 confirmed enemy aircraft the P-47 had destroyed in the European theater, the thousands of locomotives and vehicles it had hit, the miles of rail it had torn up.

“We have to revise our view of the Thunderbolt,” the author concluded. “It was not just a brute. It was a workhorse and a scalpel, depending on how you flew it.”

At the end, under a grainy black-and-white photo of a Jug in flight, they printed Sam’s contribution:

“When I first saw the P-47, I thought it was too big and too heavy for a fighter. Then I saw what it could do in a dive, how much punishment it could take, and how many friends it brought home. It taught me that an airplane isn’t what the engineers say it is on paper. It’s what it becomes when the people flying it learn how to use it.”

Sam read the article, folded the page, and tucked it into the back of his old flight logbook.

He went out to his porch that evening and watched the sunset.

On the horizon, a small private airplane buzzed by, graceful and light.

He wondered, not for the first time, what some future engineer might be saying about that airplane now.

Too slow.

Too small.

Too something.

He smiled.

Out there, somewhere, was probably another pilot about to prove them wrong.

Just like a big, heavy, “too clumsy” Jug had done all those years ago, roaring over Europe with eight guns blazing and a job to do.

THE END

News

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her Laughed—Until the Screen Changed, and the Truth Sparked the Hardest Argument of His Life

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her…

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind the $600 Million Deal That Was About to Decide Every One of Their Jobs and Futures

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind…

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the Millionaire in Line Behind Him Heard Everything—and What Happened Next Tested Pride, Policy, and the True Meaning of Help

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the…

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up a Doll, Looked Under the Bed, and Uncovered a Hidden “Secret” That Nearly Blew the Family Apart for Good

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up…

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really on His Plate and the Argument That Followed Changed Everything About What He Thought Money Could Buy

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really…

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught His Own Wife Sneaking Out and Discovered the Secret That Changed All Their Lives Forever

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught…

End of content

No more pages to load