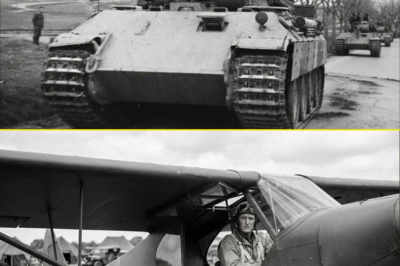

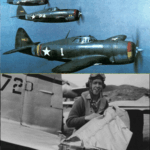

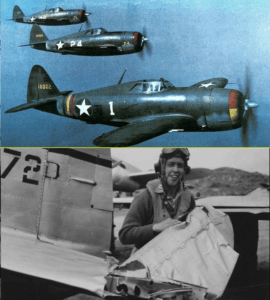

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That Weight Into a Weapon and Sent 3,752 Luftwaffe Fighters Plummeting From the Sky

The first time Lieutenant Joe Harper saw a P-47 Thunderbolt up close, he said the same thing everyone said.

“That’s a fighter?”

It sat on the pierced-steel planking of the English airfield like someone had parked a grain silo on a set of landing gear. A huge, round engine up front, a barrel of a fuselage behind it, a massive belly that looked like it could hide a small truck.

Next to it, the sleek Spitfires parked at the far end of the field looked like ballerinas. The P-47 looked like a heavyweight stepping into the wrong ring.

The crew chief, Staff Sergeant Frank Duffy, heard him and snorted.

“Yeah, Harp,” Duffy said, wiping his hands on a rag. “They told us we were gettin’ fighters. Instead we got the Brooklyn water tower with wings.”

Joe walked slowly around the big machine, craning his neck. The dorsal spine rose behind the cockpit like a small wall. The tail, when you got to it, was almost absurdly high. Under the wings, eight machine gun ports—four per wing—yawned like a row of blunt teeth.

“What’s it weigh?” Joe asked.

“Too much,” Duffy said. “Empty, about what your mom’s Buick does. Loaded, I don’t wanna think about it.”

“You got a problem with my mom’s Buick?” Joe shot back automatically.

Duffy grinned.

“Nah,” he said. “Just saying, they told us fighters had to be light. Nimble. You know, like those little Spits over there that dance around the sky. Then the eggheads show up with this thing and say, ‘Here—this is the future.’”

Joe stopped under the nose and shaded his eyes to look up at the engine.

It was a brute.

Eighteen cylinders arranged in two rows, big as a garden shed and twice as mean. Somewhere back inside the fuselage, ducting and machinery for a turbo-supercharger twisted its way to a turbine under the tail. Instead of a slim inline engine like the P-51 or the Spit, the Thunderbolt had this massive radial that gave it a face like a fist.

“What’d the engineers say?” Joe asked.

“What, when they saw it?” Duffy said. “Some loved it. Most of the old fighter jocks took one look and said, ‘Too heavy to dogfight. Too big. Too slow. Won’t turn. Might as well paint bull’s-eyes on the wings and call it a day.’”

He paused, then kicked the big main tire affectionately.

“Then they flew it,” he added. “And some of ’em changed their minds. The smart ones, anyway.”

Joe raised an eyebrow.

“Yeah?” he said. “What made ’em change?”

Duffy scratched the side of his nose.

“Well,” he said, “for one thing, it goes downhill like the world’s ending. You point this big girl at the ground, and if you’ve got altitude? Ain’t much up there that’s gonna catch you in a dive. And that big ol’ radial engine? Takes punishment like a heavyweight. Spit’s a fencer. This thing’s a barroom brawler.”

Joe smiled at that.

He liked that image.

He’d been flying for as long as the Army had let him, first Stearmans and Vultee trainers, then the nimble P-40s in stateside training. He’d pictured himself in something sleek when he got to Europe. Something that could turn on a dime and leave change. Something that looked like the posters.

He hadn’t pictured… this.

“You flown one yet?” Duffy asked.

“Orientation hop tomorrow,” Joe said. “Colonel says we’re trading our P-38s and P-39s for these. Something about range and high-altitude performance.”

Duffy rolled his eyes.

“Yeah, they love to talk about the supercharger,” he said. “How it can pull in thin air at thirty thousand like it’s sea level. How it’ll keep up with bombers all the way to Berlin and back while you boys babysit ’em.”

He leaned closer.

“Just do me a favor,” he said. “When you go up tomorrow… treat her like a lady at first, okay? Don’t go yanking and banking like you’re tryin’ to break a mustang on day one.”

“You think I’m that dumb?” Joe asked.

“I think you’re a fighter pilot,” Duffy said. “Which is the same thing some days.”

At the morning briefing, the squadron CO, Major “Red” Kearns, stood in front of a map of Europe with a pointer in one hand and a stack of papers in the other.

Kearns had the kind of weathered face you only got by flying a lot and sleeping very little. A faint white line cut across his right eyebrow—a scar from some long-ago cockpit mishap.

“All right, listen up,” he said. “For those of you who haven’t walked out to the line yet and had a heart attack, yes, we’re getting Thunderbolts. Yes, they’re huge. Yes, they look like they ate another airplane for breakfast. Get your jokes in now, because once you’ve flown them, you’re going to look stupid if you keep calling them pigs.”

There was a ripple of laughter.

“Sir,” someone in the back said, “engineers back home say they’re too heavy to dogfight.”

“Engineers back home also said we wouldn’t need more than a dozen B-17s,” Kearns replied dryly. “So you’ll excuse me if I take their opinion with a few grains of salt.”

He tapped the map.

“Here’s the deal,” he said. “Our job is changing. No more short-range sweeps where we tangle with whatever the Luftwaffe throws at us over the Channel and then scoot home for tea. Eighth Air Force is pushing deeper. Hamburg, Bremen, the Ruhr. Soon, maybe farther. They need escort. High-altitude, all the way there, all the way back. Spits can’t go that far. P-38s and P-51s are still in short supply. But we’ve got these beasts.”

He jerked a thumb toward the flight line outside.

The men shifted in their seats.

“So we’re gonna take what the engineers call a ‘too heavy’ fighter,” Kearns said, “and we’re going to learn to make that weight work for us. We’re going to use that big turbo-supercharged jungle up its tail to climb high and dive fast. We’re gonna use that armor and that big radial to bring you boys home when something else might’ve gone down in flames.”

He scanned the room.

“You fly it wrong,” he said, “you’ll be a rumor by supper. Fly it right, you’ll put holes in the Luftwaffe they don’t know how to patch.”

He nodded at the operations officer.

“For today,” Kearns said, “orientation hops only. Get a feel for her. Climb, cruise, a little gentle maneuvering. You try to turn with a Focke-Wulf like you’re in a Spit, I will personally see to it your next assignment is peeling potatoes in Reykjavik. Clear?”

“Yes, sir,” the room chorused.

“As for those engineer fellas calling it ‘too heavy to dogfight,’” Kearns added, his voice losing its formal edge just a fraction, “they’re not the ones who have to look a B-17 crew in the eye after we’ve lost half their formation. We are. So they can call it whatever they like. We’re going to call it a tool. And we’re going to learn to use it.”

The first time Joe pushed the power forward on the P-47, he understood what Duffy had meant about barroom brawlers.

The engine roared to life with a deep, throaty sound that vibrated through the seat. The propeller blurred into a silver disk. The whole airframe shook, impatient.

“Tower, this is Hellcat Two-One,” he said into the throat mike, feeling a little silly using the squadron’s new call sign. “Ready for takeoff.”

“Hellcat Two-One, cleared for takeoff,” came the reply.

He rolled onto the runway, lined up, and took a breath.

“Okay, girl,” he murmured. “Let’s see what you got.”

He pushed the throttle forward and felt the shove.

The P-47 took a moment to gather herself, then surged.

The tail lifted.

She didn’t leap into the air like the trainers had.

She strode into it.

The controls were heavier than the P-40’s had been, but not unmanageable. Just… substantial. Like moving a sturdy door instead of a screen.

At a safe speed, he eased back.

The landscape dropped away.

And then he climbed.

Oh, how she climbed.

The turbo-supercharger liked high altitude. Below ten thousand, it felt like the engine was clearing its throat. Above that, it sang.

He spiraled upward over the field, watching the altimeter tick.

Ten thousand.

Fifteen.

Twenty.

The P-47 kept going like she was barely noticing.

Up here, the English countryside looked like a patchwork blanket, the clouds like islands.

He leveled at twenty-five thousand and pushed her into a gentle turn.

That’s when he discovered something else.

She didn’t want to turn sharp.

He muscled the stick, feeling the resistance.

The big Thunderbolt rolled, but reluctantly.

He pictured a Messerschmitt 109 or a Focke-Wulf 190 dancing around him.

If he tried to out-turn one of those, he realized, he’d end up chasing his own tail while they walked their guns onto him.

He heard Kearns’s voice in his head.

You fly it wrong, you’re a rumor by supper.

“Okay,” he muttered. “No turning contests. Got it.”

He tried a dive.

He rolled the nose down slightly.

Gravity, which had grumbled about the climb, started smiling again.

The airspeed needle swept right.

Three hundred.

Three-fifty.

Four hundred.

He eased back, feeling the control surfaces stiffen as compression built.

He’d been warned about that in the briefing. High-speed dives could lock the controls. But used right…

Used right, it gave him something other fighters didn’t have.

He pulled out gently and leveled.

Everything held together.

He leveled over the field and called the tower.

“Hellcat Two-One returning to land,” he said.

“Hellcat Two-One, wind from the southwest,” came the reply. “Welcome back.”

On the ground, cracking open the canopy, he felt the adrenaline buzz in his fingers.

Duffy was waiting.

“Well?” he asked.

Joe grinned.

“She’s heavy,” he said. “But she falls like a safe.”

Duffy laughed.

“Yeah,” he said. “You learn to aim that safe just right, Krauts aren’t gonna like it.”

By late ’43, the Luftwaffe definitely did not like it.

The first few times groups of P-47s had shown up to escort bomber streams, the German pilots hadn’t known what to make of them.

From a distance, the Thunderbolt’s bulky silhouette and big radial could look like a twin-engine job. Some German aces, used to diving on what they thought were bombers, found themselves stroking their chins when those “bombers” suddenly rolled over and spat .50-caliber fire like anger from both wings.

Eight guns.

That was the other thing the engineers had given the Jug.

Eight Browning AN/M2 .50-caliber machine guns, four in each wing, with hundreds of rounds per gun.

Each one could hurl a stream of heavy bullets that chewed up metal and snapped control cables. All eight together turned a P-47 into a flying buzz saw.

“There ain’t much out there you can’t cut with eight fifties,” Kearns liked to say. “You just gotta hit ’em.”

The trick was making sure the Thunderbolt was in the right kind of fight.

For a while, the old argument simmered in mess halls on both sides of the Atlantic.

Engineers and traditionalists insisted a real fighter had to be light, nimble, quick to respond. The P-47’s high wing loading—weight divided by wing area—made it reluctant to yank and bank.

On paper, that meant “too heavy to dogfight.”

On paper, the Luftwaffe’s pilots should’ve eaten it alive.

Reality, as it often did, had other opinions.

January 1944, north of Bremen.

The weather over the North Sea had cleared just enough to tempt the planners at Eighth Air Force.

The 91st Bomb Group’s B-17s—those big Flying Fortresses everyone back home thought were invincible—climbed in their tight formations, contrails painting white streaks across the cold blue.

Joe’s group, the 356th Fighter Group, was one of the units assigned to escort them.

In the mission briefing, the intelligence officer had tapped a spot near the top of the board.

“Expect heavy Luftwaffe presence here,” he’d said. “They’ve been pulling their fighters back, conserving them for when they can hit our boys over Germany instead of wasting fuel chasing them over France.”

He’d leaned on the word our like a preacher.

The bomber crews had looked… not scared.

But focused.

They knew the statistics.

The P-47s, lined up on the runway that morning, wore their new paint jobs: olive drab tops, light gray undersides. Unit markings splashed on tails and cowlings. Some pilots had nose art half-finished.

Joe’s plane had a red cowling and the name “Miss Arkansas” in neat script under the canopy, in honor of the home-state girl whose letters he kept folded in his flight jacket.

He’d only met her once at a USO dance.

But letters traveled better than people in wartime.

“Remember,” Kearns had said before takeoff, standing on a crate so he could see everyone’s eyes. “Up there, their job is to kill bombers. Your job is to kill them before they get the chance. You see a Boche fighter lining up on a Fortress and you think, ‘Can I get there?’ the answer is yes unless your wings have fallen off.”

They’d laughed, but it was tight.

Up there, everything would compress to split-second choices.

Climb with the bombers?

Dive after a bandit?

Turn and fight or use the Jug’s speed?

Those questions were theoretical until someone was shooting at you.

They weren’t theoretical long.

At twenty-five thousand feet, the air was clear and brutally cold.

Joe’s breath fogged his oxygen mask every time he exhaled.

Ahead and slightly below, the B-17 boxes marched across the sky—three-plane elements stacked into larger formations, all moving at the same speed, the same direction, because that’s how they threw overlapping fire at anything that came close.

“Hellcat Flight, stay in Vic formation,” Kearns called over the radio from the lead ship. “Keep your eyes peeled. Contrails at eleven o’clock, high.”

Joe squinted.

He saw them.

Thin lines at first, then thickening.

German fighters.

Dozens of them.

“Fighters, three o’clock high!” someone on the bomber frequency shouted. “They’re coming around!”

The Luftwaffe had developed a tactic they called the Sturm Staffel attack—heavy armoured Focke-Wulf 190s and Bf 109s making head-on or stern passes at bomber formations, relying on concentrated cannon fire to smash through.

Escort fighters were their main worry.

On some days, during earlier raids, the bombers had outpaced or outrun their escorts, leaving them alone over target.

Those days were supposed to be over.

Today, looking at the swarm of black crosses wheeling at altitude, Joe hoped the planners were right.

“Hellcat Flight, this is Hellcat Leader,” Kearns said calmly. “Break into them. Don’t get suckered into low-altitude turning fights. Hit, dive, climb, hit again.”

“Roger,” Joe said, fingers tightening on the stick.

The German fighters came in from above and ahead, sun glinting off their wings.

For a moment, the sky looked like someone had thrown a handful of sharp stones into a river of bombers and escorts.

Then everything dissolved into motion.

Joe saw a 109 angle in on the right-hand bomber squadron, its cannon flashing.

He rolled, dove, and felt Miss Arkansas leap forward.

The Thunderbolt might have been heavy in a turn, but pointed downhill, it moved.

A line of tracers from the 109 stitched across a B-17’s nose.

Smoke burst from the Fortress’s right inboard engine.

Joe’s stomach lurched.

He didn’t have time to watch what happened next.

He was on the 109’s tail.

Not a perfect angle.

Slightly high, slightly off, but closing fast.

“Lead him,” he muttered, thumb on the gun button.

He squeezed.

The eight fifties roared.

The wing shuddered.

Shell casings cascaded out of the ejection ports like brass rain.

His tracers arced ahead of the Messerschmitt, then walked back, back, until they intersected its tail.

Chunks flew off.

A liquid streak—coolant—poured from its nose.

The 109 jinked.

Then its propeller slowed.

The pilot bailed out, a tiny figure tumbling, chute snapping open a heartbeat later.

“Scratch one,” Joe said, heart pounding.

“Nice work, Two-One,” Kearns said. “Don’t smell the roses. There’s plenty more.”

He pulled up, scanning.

Everywhere he looked, little dogfights sprouted around the bomber boxes—three 190s tangling with two Jugs, a lone 109 streaking through the formation and peeling away with half its tail missing, a Thunderbolt streaming smoke but still flying.

At one point, a Bf 110 twin-engine heavy fighter tried to sneak in low and slow.

A Jug above it rolled inverted, dropped like a stone, and with one furious burst turned the 110 into a cloud of debris.

Engineers back home, Joe thought, could have all the doubts they wanted.

Up here, the numbers were starting to tell a different story.

The tally for that day’s mission would show a dozen Luftwaffe fighters destroyed, with another handful damaged, for the loss of two P-47s and several bombers.

It wasn’t a perfect exchange.

No day in the air war was.

But it was better than many that had come before.

The Jugs had done what they were meant to do: dive into attacks, tear German fighters off the bomber’s backs, then climb back up and do it again.

They hadn’t won by out-turning anyone.

They’d won by controlling energy.

By using weight and speed in ways most ground-bound engineers hadn’t imagined when they’d shaken their slide rules and muttered, “Too heavy.”

As the months went on, the statistics piled up.

At first, it didn’t look like much.

A dozen here.

Twenty there.

Some missions were quiet; the Luftwaffe didn’t always show.

Others were wild.

Then, as Allied strategic bombing ramped up, the Thunderbolts moved into a new role: fighter-bomber.

Not only did they escort—their big radial engines making them tough to bring down with a single hit—but they also started diving on trains, flak positions, airfields.

The Thunderbolt’s weight, once a liability in theory, became an asset in practice.

You could hang bombs under this thing.

Lots of bombs.

Or rockets.

Or both.

And that big radial, that thick “jug” of a fuselage, could take hits from small arms and flak that would have shredded lighter fighters.

Every bullet it absorbed without disintegrating was one more minute for a pilot to limp home.

Every time a pilot who should’ve been dead rolled to a stop back at base with half his cylinders shot out, the crews got a little more fond of the “too heavy” design.

April 1944, France.

They called it “rhubarb” work: low-level sorties where a few fighters would peel off from escort duty or fly specific missions to harass anything moving on roads and rails.

Joe’s squadron had been given a stretch of railway the planners believed the Germans were using to shuttle fuel and troops toward the coast.

“Anything with a black cross, blow it up,” Kearns said at briefing. “Anything with a swastika, blow it up. Anything that looks like it’s helping the swastikas get around, blow that up too. Just watch your fire near civilians. We’re here to break their war, not their country.”

That was a line Joe appreciated.

War had a way of blurring lines until you needed someone to say them out loud.

Miss Arkansas taxied with two 500-pound bombs under her wings and a belly tank slung underneath.

The Jugs lifted from the field, climbed a bit, then dropped to the deck once they were over the Channel.

Flying a Thunderbolt at treetop level was a different kind of thrill than high-altitude escort.

The speed felt faster, the ground rushed by in a blur, and every hedgerow and hill looked like it was trying to leap up and smack you.

“Hellcat Flight, stay in line abreast,” Kearns said. “Eyes out. Watch for flak trucks. If you see flashes, jink.”

Almost an hour into the run, they spotted a train.

It snaked along a stretch of track near a small town, black smoke puffing from its locomotive.

On some days, the Luftwaffe might’ve had fighters patrolling nearby.

Today, the sky above was empty.

“Here we go,” Kearns said. “Two-Flight, you take the front. Three-Flight, the back. One-Flight, you get the middle. Hit the locomotive and the tank cars if you can.”

Joe’s mouth went dry.

He’d dropped bombs in training.

He’d strafed trucks and warehouses.

But there was something about a moving target like that, all that mass and momentum, that made the stakes feel different.

He rolled Miss Arkansas into a shallow dive.

The train grew larger in his windscreen.

He saw the locomotive engineer’s tiny figure leaning out of the cab, looking up.

“Sorry, pal,” Joe muttered. “Wrong war, wrong side.”

He released at just the right moment, judging speed and angle.

The Jug jumped as the bomb left its wing.

He pulled up, jinked, and looked over his shoulder.

The 500-pounder dropped, slowed, then hit the track just ahead of the locomotive.

The world went briefly white and gray.

When the smoke cleared, the front of the train was off the tracks, cars jumbled.

Secondary explosions marched along the line as other Jugs’ bombs found tankers.

Fireballs bloomed.

“Nice one, Two-One!” Kearns whooped. “Get those guns ready. We’re gonna clip its wings.”

They came back around, lower this time, strafing along the length of the train.

Eight fifties chewed through steel like an angry saw. Sparks flew. Wheels shattered.

Anti-aircraft fire—light stuff, from trucks or hasty gun pits—stabbed up, but the P-47s were there and gone too fast, their armor shrugging off near-misses.

Back at base that night, the intelligence officer showed them reconnaissance photos.

Burned train.

Scarred tracks.

Disrupted timetable.

“Another piece off their board,” he said.

The P-47s kept flying that kind of mission.

By the time Allied troops went ashore on D-Day and pushed inland, the Thunderbolts had become a familiar and welcome sight to ground troops.

“Every time I heard that big radial up there,” one infantryman would say years later, “I figured somebody on the other side was about to have a real bad day.”

Not every Thunderbolt story was a clean hit and a safe landing.

It was war.

Some P-47s didn’t come back.

Others limped in, full of holes.

During one mission over France, Joe’s wingman, Lieutenant Fred “Tex” Doyle, got too focused on a juicy convoy target and flew straight through a flak trap.

A 20-millimeter shell punched through his wing root.

Another shattered part of his canopy.

Joe saw his Jug jerk, saw pieces fly.

“Tex!” he shouted into the mic. “You hit?”

Tex’s drawl came back, strained but alive.

“Little bit, Harp,” he said. “Got some extra air-conditioning where I didn’t order it.”

“Can you climb?” Joe asked.

“Engine’s runnin’ rough,” Tex said. “Oil pressure’s low. She’s shakin’ like a leaf.”

Joe slid into formation with him, close enough to see Tex’s pale face.

The Jug’s right side was a mess—holes in the wing, a jagged wound near the cockpit, oil streaking along the fuselage.

In a smaller fighter, Joe knew, that kind of damage might have meant an explosion, a fireball, nothing left.

In the Thunderbolt, it meant a long, nerve-wracking ride home.

“Hang in there,” Joe said. “We’ll nurse her back.”

They climbed, slowly, babying the gas.

Once they crossed the Channel, Tex’s engine coughed.

He lost some power.

But the Jug kept flying.

When they finally reached the field and Tex touched down, his landing was ugly and hard, but the big fighter stayed in one piece.

The crew chiefs counted the holes.

“Twenty-seven,” Duffy said. “I’m gonna need a bigger patch kit.”

Tex limped away from his plane and looked back at it, shaking his head.

“Too heavy to dogfight, huh?” he said. “Feels just about heavy enough to bring my sorry hide home.”

The crew laughed.

Later, when mechanics back in the States analyzed combat reports and wreckage, they’d marvel at how often the P-47 brought pilots home with damage that would’ve been fatal in something else.

They’d add more armor in smart places.

They’d tweak systems.

They’d keep shipping Thunderbolts to Europe and the Pacific, where they’d fly from rough strips and take on roles that would have crushed lighter airframes.

The engineers who’d once complained about weight began to talk about “structural robustness” instead.

Sometimes reality changed minds.

Sometimes performance dragged opinion along behind it.

Autumn 1944.

By now, the numbers were starting to speak loudly.

P-47 units in the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces had racked up hundreds of aerial victories over the Luftwaffe—fighters, bombers, even the occasional unfortunate transport caught in the wrong patch of sky.

In addition, they’d destroyed or damaged thousands of vehicles on the ground.

Trains.

Tanks.

Trucks.

Anything that moved.

The Luftwaffe, bled white by years of attrition, found itself struggling to put experienced pilots in new aircraft. Some squadrons were filled with kids barely out of training, thrown into combat against seasoned Thunderbolt jocks who’d cut their teeth over Bremen and the Ruhr.

On one chilly morning, Joe and his squadron got orders for a “fighter sweep” over central Germany.

No bombers to babysit.

No bridges to hit.

Just patrol and tangle with whatever the Germans could still put in the air.

“You might get quiet skies,” the briefing officer said. “You might fly into a hornet’s nest. Be ready for both.”

Kearns, pulling on his gloves afterward, looked at Joe.

“You know what we’ve done, right?” he asked.

“In what sense, sir?” Joe said.

“Kill tallies,” Kearns said. “Not just ours. All P-47 drivers.”

Joe had seen some numbers.

Charts on walls.

Black silhouettes of enemy planes painted on fuselage sides.

“Over three thousand Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed,” Kearns said quietly. “Fighters, mostly. Some bombers. That’s what they’re saying.”

Joe blinked.

“Three thousand,” he repeated.

“Three thousand seven hundred fifty-two is the last tally I heard from group Intel,” Kearns said. “Give or take. For a fighter that was ‘too heavy to dogfight.’”

Joe exhaled.

It was just a number.

An abstract way of summing up a thousand individual fights.

A thousand split-second decisions.

A thousand chutes opening—or not.

But it meant something.

It meant the runway wasn’t as crowded with enemy fighters anymore.

It meant bombers made it home that would’ve gone down.

It meant ground troops didn’t have to look over their shoulders as often for swooping, screaming shapes with black crosses.

“You proud of that?” Kearns asked.

Joe thought.

“Proud we did our job,” he said. “Sad we had to.”

Kearns nodded.

“That’s the right answer,” he said. “Now let’s go see how many of them still feel like coming up to play.”

They found out over Kassel.

The Luftwaffe, sensing the end but determined not to go quietly, had massed a group of Bf 109s and Fw 190s to contest the area.

Joe’s squadron and two others flew into a sky that quickly turned into a chaotic dance of contrails and tracers.

This time, the Germans were aggressive.

They dove from the sun, cannons blazing, aiming to break up the American formations before they could use their speed and dive.

Teams of Thunderbolts used the tactics they’d honed.

They didn’t try to out-turn.

They didn’t get stuck in long, flat circling fights.

Instead, they dove, hit, and zoomed.

Joe latched onto a 190 that had just streaked through an American formation, damaging a Jug’s tail.

He rolled into a shallow dive, gaining speed.

At four hundred miles an hour, the P-47 felt like a bullet.

He lined up, squeezed the trigger.

The eight guns roared.

His tracers hit the Focke-Wulf’s wing root and walked inward.

The 190 snapped into a roll as its pilot bailed out.

Joe pulled up hard, feeling the onset of compression.

For a moment, his controls stiffened.

He held his breath, eased off a little, and felt them respond again.

Two German fighters latched onto his tail.

He saw their shadows flicker.

He rolled inverted, then pulled, diving away.

Bullets stitched the air where he’d been.

He went down, down, down, the altimeter unwinding.

At a low altitude, he leveled, kicked the rudder, and jinked.

The Germans followed—but one of them misjudged, lost speed, and ended up in front of another Thunderbolt coming the other way.

A quick burst.

Another black cross turned into a smear of smoke.

The fight went on for fifteen minutes that felt like fifteen years.

When they finally re-formed and pointed their noses home, Joe counted heads.

They’d lost one.

Lieutenant Parks.

No chute.

The price was always there.

No matter how good the machine, how skilled the pilot, how favorable the tactics, war took its share.

But the scoreboard would show something else that day.

Ten enemy fighters destroyed.

Six probables.

A few more damaged.

Engineers who’d stared at weight charts and wing loading figures now had to stare at the tallies.

3,752 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed by P-47s over the course of the war.

That number didn’t erase the losses.

It didn’t erase the cost.

But it stuck a fork in the idea that the Thunderbolt had been a mistake.

Years after the war, long after the last P-47 had been retired from front-line service and many had been sold to foreign air forces or turned into gate guardians at airfields, Joe stood in a museum in Ohio and stared up at one suspended from the ceiling.

She looked smaller indoors.

Shinier.

The paint was perfect, the invasion stripes crisp, the nose art carefully restored: a pinup girl leaning against a lightning bolt, the name “Lucky Lady” cursive under the cockpit.

A plaque nearby listed statistics.

Republic P-47D Thunderbolt. Fighter-bomber. Engine: Pratt & Whitney R-2800 radial. Armament: eight .50 cal machine guns, up to 2,500 pounds of bombs/rockets. Over 15,000 produced. Credited with destroying 3,752 enemy aircraft in air-to-air combat in the European theater.

A little boy stood next to Joe, reading.

“Three thousand seven hundred fifty-two,” the kid said, sounding out the number. “Whoa.”

His grandfather, wearing a baseball cap with “WWII Veteran” embroidered, nodded.

“That’s a lot of planes,” the old man said.

“Was it really too heavy?” the boy asked. “It says here some people said it was too heavy to dogfight.”

Joe smiled, unseen.

He’d heard that line for most of his life.

He’d heard it in training, in mess halls, even at post-war cocktail parties where someone who’d read half a book would say, “You flew Thunderbolts, right? Weren’t they kind of… big?”

He’d always answer the same way.

“Big enough to bring me home,” he’d say.

The boy’s grandfather chuckled.

“They said a lot of things back then,” he said. “Some people looked at it and said, ‘Too heavy. Won’t turn. Bad idea.’ Others looked at it and said, ‘Big engine, big guns, strong frame. We can do something with this.’”

“Which ones were right?” the boy asked.

The old man pointed at the plaque.

“That number up there,” he said. “That’s your answer.”

He put a hand on the boy’s shoulder.

“Sometimes,” he said, “you can’t tell what something’s good for until you stop asking it to be something it’s not. The P-47 wasn’t built to be a ballet dancer. It was built to hit hard, dive fast, and take a beating. Once pilots learned to fight its way instead of someone else’s, it did just fine.”

The boy thought about that.

“So… like if I’m big and everyone says I shouldn’t play shortstop,” he said, “but I’m real good at pitcher instead?”

The grandfather laughed.

“Exactly,” he said. “You don’t tell a Thunderbolt to twirl. You tell it to punch.”

Joe felt a lump in his throat.

He wondered how many of the engineers who’d grumbled about weight had later watched combat footage and revised their opinions.

He wondered how many young pilots had looked at the big, ungainly thing on the tarmac and felt the same doubt he had, only to fall in love with it at twenty thousand feet.

He wondered, briefly, about Miss Arkansas.

She hadn’t made it to any museum.

She’d been lost near the end of the war, when a rookie pilot flying her tried to out-turn a 190 over the Ardennes and paid the price.

Joe had been sick for days.

Not just for the plane.

For the kid.

For the reminder that every lesson in tactics was written in someone’s blood.

He took a breath, pushed the memory down gently, and focused on the Thunderbolt above him.

“Too heavy to dogfight,” he murmured.

Maybe, on a blackboard.

Definitely not, in the skies over Europe and the Pacific, where weight could be turned into momentum, where a big radial could soak up hits, where eight fifties could turn enemy fighters into falling wreckage and armored trains into scrapyards.

It had never been about being the most graceful.

It had always been about getting the job done.

He stepped back, gave the big fighter one last look, and smiled.

“You did all right, Jug,” he said softly.

Then he turned and walked toward the exit, the echo of a big radial engine humming somewhere in the back of his mind, mingling with the distant voices of men he’d flown with.

Engineers could argue.

Historians could debate.

Pilots remembered.

They remembered how the “flying tank” had climbed with them into hostile skies.

How it had shrugged off hits that should’ve been fatal.

How it had turned shallow dives into sledgehammer blows against an enemy that had once ruled the air.

And somewhere, in the logbooks of squadrons scattered across old bases in England and France, the tally sat inked in neat columns:

Enemy Aircraft Destroyed (Air-to-Air): 3,752.

Numbers on paper.

Stories in the sky.

THE END

News

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six Hours Later, His Lone Gamble Turned Their Mockery into Shock, Freedom, and a Furious Argument in the War Room

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six…

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare Rifles, Ignored His Own Commissar’s Orders, and Turned One Hill Into a “Forest of Ghosts” That Killed 225 Attackers and Broke the Siege

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare…

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion, Claimed Ninety-Six Enemy Combatants Without a Single Direct Shot, and Sparked One of the War’s Most Tense Command Arguments

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion,…

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane, Dove Through Fire, and Knocked Out Six Panzers to Save 150 Men

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane,…

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to Notice — But What He Saw, What He Asked, and the Argument That Followed Changed the Boy’s Entire Life Forever

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to…

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet Single Dad Janitor Stood Up, Walked to the Defense Table, and Changed Everything

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet…

End of content

No more pages to load