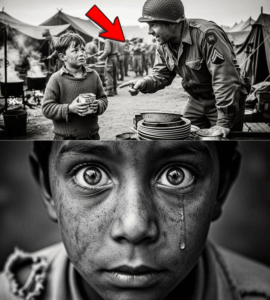

Caught Stealing Bread in a Ruined City, a Terrified German Boy Braced for an American Soldier’s Fury—What Happened Next Changed Both of Their Lives and an Entire Village Forever

Emil had been hungry for so long that hunger no longer felt like a feeling. It felt like a place.

It was the broken doorway where he slept with his little sister Anna curled against his chest. It was the empty cupboard in the apartment that no longer had windows. It was the crunch of plaster and glass under his bare feet when he woke in the middle of the night, stomach clawing at his spine, and went searching for something—anything—left behind in the ruins.

And on that gray afternoon, hunger pushed him through the shattered streets toward the smell of bread.

The American supply truck was parked beside the old town square, its olive-drab side marked with white numbers that meant nothing to him. What mattered were the wooden crates stacked at the back, and the soldiers laughing, their gloves brushing crumbs from their uniforms.

Bread. Real bread. Not the hard, stale crusts neighbors guarded like treasure, not the watery broth given out by relief workers when they came through once a week. These loaves were round and full, with crackling brown tops and tiny clouds of steam curling into the December air.

Emil hovered behind the twisted frame of a doorway, hands shoved into his ragged coat, watching. His heart pounded so loudly he feared the soldiers would hear it.

He counted them.

One at the back of the truck, talking to a man with stripes on his sleeve. Two more stood nearby, smoking and arguing about something in rapid English. Another watched the road with a bored expression, his rifle slung across his chest.

Four. Four soldiers, four rifles, and a truck full of bread.

“Don’t,” Anna had whispered that morning, when he’d told her his plan. Her eyes, too big for her thin face, had filled with tears. “Emil, they have guns.”

“So does everyone,” he’d snapped, more sharply than he meant, then softened. “We can’t stay hungry forever, Anna. I’ll be careful.”

Now, hiding among the ruins, he thought of her sitting on the cold floor, hugging her knees beneath the blanket they shared. Her lips had cracked from dryness. She wasn’t complaining anymore, and that scared him most. Complaining meant you still believed someone might fix it.

He had to bring her something. Just a loaf. One loaf.

The soldier at the back of the truck turned to grab another crate, his back fully exposed. The others shifted their attention to him as he started talking, his hands drawing shapes in the air like he was telling a story.

There. That was the moment.

Emil took a breath so deep it hurt his ribs, then slipped from the doorway and ran.

He moved low, the way he’d seen stray dogs move, quick and close to the ground. The cold air burned his lungs. His boots—two sizes too big, taken from a cousin who’d gone and never come back—slapped the cracked pavement.

He reached the back of the truck unseen.

Up close, the smell was overwhelming. Yeast and warmth and salt, everything his life had not been for months. His hands were shaking so badly he almost fumbled the first loaf. He pulled it close to his chest, like a baby, then grabbed a second.

Just one more. Just in case.

“Hey!”

The shout hit him like a physical blow.

Emil froze. The loaf slipped from his grasp and tumbled to the ground, rolling through a smear of gray slush.

He spun and tried to run, but a hand closed around the back of his coat and yanked him backward. He fell, the breath slammed from his lungs as he hit the ground. The world blurred for a second.

Then the American was standing over him.

He was younger than Emil expected, maybe in his mid-twenties, with tired blue eyes and a square jaw darkened by stubble. His helmet was pushed back a little, and there was a smear of grease on his cheek. His gloved hand still gripped Emil’s coat.

The soldier’s eyes dropped to the fallen loaf of bread, then to Emil’s thin face.

The yelling brought the others.

“What’s going on, Miller?” one of them called.

“Kid tried to lift our bread,” the first soldier replied without looking up.

Hands grabbed Emil’s arms, hauling him to his feet. Someone cursed in English. Another soldier stepped forward, his stripes marking him as the man in charge.

The sergeant.

He looked Emil up and down, his gaze taking in the patched coat, the dirty knees of his trousers, the shoes with the worn-out soles. His eyes were hard.

“Stealing from the U.S. Army, huh?” he said slowly, in heavily accented German. “That’s a serious thing, Junge. Very serious.”

Emil understood enough to know he was in real trouble. His knees started to tremble. He tried to speak, but the words stuck behind his teeth.

The first soldier—Miller—gave him a little shake. “You speak English?” he asked, his tone more curious than cruel.

Emil swallowed. “A little,” he whispered, his own accent thick and clumsy. “School… before.”

“Before,” Miller echoed softly, and something flickered in his eyes.

“He’s a thief,” the sergeant said flatly. “Regulations are clear. We can’t have these kids crawling all over our supplies. Next time it’s not just bread.”

The other soldiers muttered in agreement. One of them said something about setting an example.

Miller’s jaw tightened. His grip on Emil’s coat loosened, just slightly.

“He’s skin and bone, Sarge,” Miller said. “Look at him. He’s what—twelve? Thirteen?”

“Fourteen,” Emil whispered, though he wasn’t entirely sure anymore. Birthdays were something from another world.

The sergeant looked unimpressed. “He knows what he’s doing. He gets away with it, then his friends try it. Then he’s cutting canvas or siphoning gas. Rules are rules.”

He took a step closer, looming over Emil. “You know what we do with thieves, boy?”

Emil’s breathing grew shallow. He’d heard stories. Men taken away. Men who didn’t come back.

His vision narrowed, sound dropping to a distant murmur. His body wanted to run, but there was nowhere to go, nothing he could say that would matter.

Miller stepped between them.

“Sergeant, with respect,” he said, voice low but firm, “we’re not on the front line anymore. The war’s over. We’re supposed to be helping these people get back on their feet, not—”

“Helping them doesn’t mean letting them rob us blind,” the sergeant snapped. “You’ve been here long enough to know that, Miller.”

The air between them crackled. The other soldiers went quiet, watching.

Emil stood caught between them, a ragged scarecrow in a too-big coat, as two armed men argued over his fate.

“The kid’s starving,” Miller insisted. “So are half the people in this town. You think throwing him in some camp is going to fix that?”

The sergeant’s eyes flashed. “This isn’t about fixing everything. It’s about order.”

Their voices rose, German and English tangling in the air. The argument sharpened, becoming serious, tense, each word like a step closer to some invisible cliff.

Emil looked from one to the other, not understanding every word but feeling the danger rise like the wind before a storm. The sergeant’s hand brushed the butt of his sidearm, an unconscious gesture. One of the other soldiers shifted his weight, boots scraping on the frozen ground.

Miller noticed. His expression changed, the heat in his eyes cooling into something more controlled.

“Let me handle this,” he said at last, his voice quieter but no less determined. “I caught him. Let me decide what to do with him. Within reason.”

The sergeant studied him. The silence stretched.

Finally, he exhaled through his nose. “Fine,” he said. “He’s your problem now. But if I see him near this truck again, I’ll deal with him my way. Understood?”

Miller nodded once. “Understood.”

The tension eased, if only a little. The other soldiers drifted back to their tasks, though they kept glancing over, curiosity written all over their faces.

Miller turned to Emil and released his coat. Emil swayed but kept his feet.

Up close, the American’s eyes weren’t hard at all. They were tired, yes, but there was something else there. Something that looked a little like pity, and a little like recognition.

“What’s your name, kid?” Miller asked.

“Emil,” he whispered.

“Emil,” Miller repeated, testing the sound. “You got family, Emil?”

For a heartbeat, Emil thought about lying. About saying no, that there was no one, that taking him away would hurt no one. But Anna’s face rose in his mind.

“My sister,” he said. “Anna. She is nine. Our parents…” The words faltered. He shrugged instead. “Just us.”

Miller’s jaw worked for a moment, as if he were chewing something difficult. His gaze flicked to the fallen loaf, now ruined by slush.

“You tried to steal two?” he asked.

Emil hesitated, then nodded. “One for me. One for her.”

Miller looked down, then back up. “All right,” he said. “You’re coming with me.”

Fear slammed into Emil so hard he almost doubled over. “Please,” he blurted out. “I am sorry. I will not—”

Miller held up a hand. “Relax. Take it easy. I’m not throwing you in a camp.” He glanced toward the sergeant, then leaned closer, dropping his voice. “But we can’t talk about this here. You understand? Too many eyes.”

Emil swallowed, confused but hopeful. “Where?” he asked.

“Where you live,” Miller said. “You’re going to show me. And if you’re lying about that sister, I swear you’ll wish you hadn’t tried to grab that bread.”

The warning was real, but there was no cruelty in it. That puzzled Emil almost as much as everything else.

He nodded.

Miller grabbed two fresh loaves from the crate, tucking them under one arm. The sergeant’s eyebrows shot up, but he said nothing as Miller slung his rifle over his shoulder and jerked his chin at Emil.

“Let’s go,” he said.

They walked through the broken streets, side by side.

Emil led the way, darting glances at the soldier. Miller’s boots crunched over rubble. Every so often he looked around, taking in the collapsed roofs, the walls blackened by fire, the empty spaces where houses once stood.

“Used to be a nice town?” he asked.

Emil nodded. “There was a fair in the square. Every summer. Music, lights.” He tried to picture it, but the memories were hazy, fading behind months of fear and sirens and running.

“You go to the fair?” Miller asked.

“Once,” Emil said. “My father won a toy for Anna. A bear.” He smiled faintly. “She still has it. One ear.”

They turned down a narrower street, where the damage was worse. Windows gaped like missing teeth. A bicycle lay twisted in a doorway, rust eating at its frame.

Finally, Emil stopped in front of what had once been an apartment building. Now it was a skeleton of brick and broken beams, open to the gray winter sky.

“We live here,” he said.

Miller stared. “Here?”

“We have one room,” Emil said. “Not all the building. Come.”

He climbed carefully over the collapsed steps, using the path he and Anna had worn through debris. Miller followed, the loaves still tucked under his arm, his rifle bumping against his back.

They entered what had once been a second-floor apartment, now exposed where an entire wall had blown away. A jagged edge of floor marked the borderline between shelter and open air. Someone had hung a blanket from a bent pipe to block the wind. It fluttered weakly.

Anna sat in the corner, near the remains of a stove. She looked up at the sound of their footsteps, her eyes going wide when she saw Miller.

She scrambled to her feet, backing against the wall. The stuffed bear dangled from one hand, its fabric threadbare.

“It’s okay,” Emil said quickly, raising his hands in what he hoped was a calming gesture. “He is… he is American. He will not hurt us.”

“That depends,” Miller said, but his voice was gentle. “You must be Anna.”

She said nothing, only nodded once.

Miller stepped inside, looking around. There were two blankets, a chipped plate, a dented pot, and a few small, precious items piled carefully on a shelf: a photograph in a cracked frame, a wooden horse with one missing leg, a book with its cover half burned.

And that was all.

No food. No coal. No stored supplies tucked away for later.

Nothing.

Miller’s face tightened. He unslung the loaves of bread and set them carefully on the chipped plate, as if the plate were made of crystal.

“Okay,” he said quietly. “Now I understand.”

Anna’s eyes fixed on the bread. She licked her cracked lips unconsciously, then glanced at Emil, waiting for permission.

Emil nodded, stunned. “You can… we can…?”

“For now,” Miller said. “Go ahead. Eat.”

They didn’t need to be told twice.

Anna reached first, fingers trembling, while Emil forced himself to move slowly, to take only a piece. The bread was still warm. When he bit into it, the crust crackled and the soft interior pressed against his tongue like some impossible luxury.

For a moment, he forgot the American was there. He forgot the ruined street, the cold, the fear.

He just chewed, and swallowed, and felt something inside him relax for the first time in weeks.

When he finally looked up, Miller was watching them with an expression Emil couldn’t read.

“You said your parents are gone,” Miller said softly. “How?”

Emil hesitated. It wasn’t a story he liked to tell.

“There was a raid,” he said at last. “We were in the cellar. The building… fell. I was at my uncle’s house that night. When I came back…” He gestured vaguely at the collapsed wall. “Only this part was left. The rest…”

His voice trailed off. Anna reached for his hand. He squeezed it.

Miller nodded slowly. “I’m sorry,” he said.

The words were simple, but he said them like he meant them.

Emil studied him. “Do you have family?” he asked, surprised at his own boldness.

Miller’s gaze drifted to the hole where the wall had been, to the gray sky beyond. “Yeah,” he said. “Back in Ohio. A mom who sends too many letters. A dad who pretends he’s not scared. A kid brother who joined up as soon as he could and…” He stopped.

“And?” Emil asked.

Miller’s jaw clenched. “He didn’t make it,” he said quietly. “Different front. Different day. Same sky when it happened, I guess.”

For a moment, the broken apartment was very still.

“I am sorry,” Emil said, echoing the soldier’s words.

Miller gave a brief, crooked smile. “Thanks.”

They sat in silence for a while, the only sounds the soft tearing of bread and the distant rumble of a truck somewhere in the town.

Finally, Miller cleared his throat.

“Listen,” he said. “You can’t steal from the supply trucks again. You understand? If the wrong person catches you next time, I might not be able to talk them down. And I really don’t want to see you get hurt over a loaf of bread.”

Emil nodded quickly. “I understand. I will not—”

“But,” Miller continued, “I also can’t just leave you two here to… to fade away. That’s not happening on my watch.”

He rubbed a hand over his face, thinking.

“There’s a church a few streets over,” he said at last. “Some relief people set up a kitchen there. They give out soup, sometimes clothes. You know it?”

Emil nodded. “But there are so many people. We go when we can, but… sometimes there is nothing left.”

“Yeah,” Miller said. “I’ve seen the lines. It’s not enough.”

He stood abruptly, made a decision, then looked down at them. “Here’s what we’re going to do.”

Over the next hour, the apartment, for the first time in a long time, became a place where plans were made instead of merely endured.

Miller went back to his unit and returned with a small bag of supplies: a few more loaves, some canned meat, a handful of potatoes that looked like they’d seen better days but were still good enough to eat. He brought an old wool coat someone had left behind and an extra pair of socks.

“These are from guys who rotated out and didn’t want to carry everything,” he explained. “No one’s going to miss them.”

The second time he returned, the sergeant came with him.

Emil’s heart dropped into his shoes at the sight of the man in the doorway, his broad shoulders filling what was left of the frame.

But the sergeant’s eyes were different now. Less judgmental. More calculating.

“So this is where you live,” he said to Emil, his German slow and careful. “No other family?”

“No, Herr—” Emil started, then corrected himself. “No, Sergeant.”

The sergeant stepped inside, his heavy boots making the floor creak. He looked around, taking in the same details Miller had: the thin blanket, the chipped plate, the empty shelf.

He grunted.

“All right,” he said to Miller. “You were right. The kid’s not running some operation. He’s just trying not to starve.”

“I told you,” Miller said.

The sergeant shot him a mildly exasperated look. “Don’t let it go to your head.”

He turned back to Emil. “Listen to me carefully, Junge. I’m not promising miracles. We’re not here forever, and we don’t have enough for everyone. But we can do something.”

He pointed a finger at Emil’s chest. “You don’t come near the trucks again. Not ever. Instead, you come to the church kitchen every morning. You help there—wash pots, carry water, whatever they tell you. In return, you and your sister eat. Understood?”

Emil’s eyes widened. “Every day?” he asked, hardly believing.

The sergeant nodded. “As long as the kitchen is open and as long as you behave.”

“And if I do not?” Emil asked quietly.

The sergeant’s face hardened. “Then we go back to the conversation we had at the truck, and I stop letting Miller talk me into things.”

Emil gulped. “I will behave,” he said quickly.

The sergeant’s mouth twitched, like he was suppressing a smile. “Good.”

“And one more thing,” Miller added. “You’re not alone out there. If anyone gives you trouble—other kids, grown-ups, whoever—you tell the people at the kitchen. You tell them Sergeant Davis or Private Miller sent you. That should mean something, at least for now.”

Emil didn’t know what to say. Gratitude swelled in his chest until it almost hurt. He looked at Anna, who clutched her bear and stared at the two soldiers as if they were figures from one of the fairy tales their mother used to tell.

“Thank you,” Emil said, the words feeling too small. “Really. Thank you.”

“Don’t thank us yet,” the sergeant said gruffly, turning toward the door. “Thank us by showing up tomorrow and the next day and the day after that. No more stealing.”

He stepped out, his silhouette briefly framed against the gray light before he disappeared.

Miller lingered.

“You see?” he said softly. “Sometimes arguments help. Even when they get serious.”

Emil thought of the raised voices at the truck, the way the air had crackled with tension. That argument had felt like a battle in itself, a clash that could have gone very wrong.

But it hadn’t. Because one man had refused to look away. Because he’d insisted there was more than one way to follow rules.

“Will you… be here?” Emil asked. “In the town, I mean. For long?”

Miller shrugged one shoulder. “Hard to say,” he replied. “Orders change. We go where we’re told.”

He looked at Anna, then back at Emil. “But I’ll be around for a while. Helping at the church sometimes. Checking the lines. Making sure certain kids remember our agreement.”

His tone was light, but his eyes were serious.

“I will remember,” Emil said.

Miller nodded. “Good.”

He started to leave, then paused, his hand resting on the broken doorframe.

“You know,” he said, “back home we’ve got this saying—‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ Means it could be any of us in your shoes. Or you in mine. Life tosses people around like dice.”

Emil frowned, trying to understand.

“You think you could be… me?” he asked.

“Sure,” Miller said. “Different country, different uniform, same hunger.” He smiled, but there was sadness in it. “Maybe that’s why I grabbed you instead of just yelling. I saw a little of my brother in you. A little of myself, even.”

Emil didn’t know what to say to that.

“Anyway,” Miller went on, straightening up, “we’ll see each other tomorrow. Early. The line at the kitchen gets long.”

He stepped out into the cold air, his footsteps fading down the corridor.

For a long time after he left, Emil and Anna sat in the quiet apartment, each lost in their thoughts.

“Do you think he is… good?” Anna asked at last. “The American?”

Emil considered. The world, as he’d learned, rarely offered simple answers. People were not just good or bad; they were tired, or scared, or angry, or kind in small, surprising ways.

“I think,” he said slowly, “he is trying.”

Anna nodded, as if that was enough.

That night, they slept with full stomachs. The cold was still there, the cracks in the walls still let in the wind, but hunger no longer gnawed at them with the same ferocity.

In the days that followed, the plan held.

Every morning, Emil and Anna walked to the church. The kitchen there was a noisy, chaotic place filled with steam and the clatter of pots. Women in worn coats stirred huge pots of soup. Men carried sacks of flour. A priest moved among them with tired eyes and a gentle smile.

At first, some of the volunteers eyed Emil warily. A street boy could be trouble. But when he rolled up his sleeves and started scrubbing pots until his fingers wrinkled, their attitudes softened.

“He works hard,” one of the women remarked. “Doesn’t complain.”

“Private Miller sent him,” another added. “And the sergeant. Better we keep him busy than let him run wild.”

Emil didn’t understand every word, but he understood enough.

He saw Miller there often, carrying crates, joking with the cooks, listening to the priest. Sometimes Miller would ruffle Anna’s hair or toss her an apple when he thought no one was looking.

The sergeant came too, less often but still regularly. He watched everything with a sharp eye, but he also lifted sacks of potatoes like they weighed nothing, and once Emil saw him carefully adjust an old woman’s scarf to better cover her ears against the cold.

The argument at the truck was not forgotten, but it became something else in Emil’s mind. Not just a memory of fear, but a turning point. A moment when two men had clashed over what to do with him, and mercy had won.

One afternoon, weeks later, when the worst of the winter was finally starting to loosen its grip, Emil walked home from the church with a small bundle under his arm—bread, potatoes, and a bit of dried meat.

The town was still broken, but here and there he saw signs of life. Someone had swept the front of their shop, even though the windows were still gone. Children played a cautious game of tag in the rubble. A woman hung laundry from a line strung between two shattered walls.

He paused in the square where he’d first seen the truck.

The truck was gone now, sent somewhere else, but he could still smell bread if he tried. He remembered the terror of that first moment, the rough grip on his coat, the sergeant’s hard eyes.

And he remembered Miller’s hand, reaching past fear and anger and regulations toward something else.

“Thank you,” he whispered to the empty air, feeling a little foolish and not caring at all.

The wind picked up, swirling dust around his feet.

He thought of the future—of repairs to the apartment, of maybe going back to some kind of school if one ever opened again, of helping at the church kitchen until he wasn’t needed there anymore.

He thought of the American soldier from Ohio who had seen him not as an enemy or a problem to be solved, but as a boy with a sister and an empty stomach.

The war had taken much from Emil. Too much. But it had also, strangely, given him this: a reminder that even in the worst ruins, people could still choose how to treat each other.

He turned toward home, the bundle of food warm against his chest, Anna’s smile already forming in his mind.

In the distance, a truck engine rumbled. Perhaps Miller was riding in it, heading to some other part of town, some other task. Perhaps not.

Either way, the path that had opened that day by the truck—through a tense argument, a risky decision, and an unexpected act of kindness—would stay with Emil for the rest of his life.

Years later, when the city had rebuilt itself with new windows and fresh paint, when laughter once again filled the square on summer evenings, Emil would tell Anna’s children about the American who caught him stealing and chose to do something different.

He would tell them that sometimes the bravest thing a person could do was not to raise their voice or their fist, but to say, in the middle of anger and fear, “Wait. There is another way.”

And every time he told the story, he would feel again the rough grip on his coat, the pounding of his heart, and the incredible, impossible taste of warm bread in a ruined world.

THE END

News

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

The Hour That Shook Two Nations

After watching a mysterious 60-minute demonstration that left him speechless, Churchill traveled to America—where a single unexpected statement he delivered…

The General Who Woke in the Wrong World

Rescued by American doctors after a near-fatal collapse, a German general awakens in an unexpected place—only to witness secrets, alliances,…

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning

American generals arrived in Britain expecting orderly war planning—but instead uncovered a web of astonishing D-Day preparations so elaborate, bold,…

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline. The Fake Takedown Video That Fooled Viewers, Enraged Comment

Rachel Maddow Didn’t Say It. Stephen Miller Never Sat in That Chair. But Millions Still Clicked the “TOTAL DESTRUCTION” Headline….

“I THOUGHT RACHEL WAS FEARLESS ON AIR — UNTIL I SAW HER CHANGE A DIAPER”: THE PRIVATE BABY MOMENT THAT BROKE LAWRENCE O’DONNELL’S TOUGH-GUY IMAGE. THE SOFT-WHISPERED

“I THOUGHT RACHEL WAS FEARLESS ON AIR — UNTIL I SAW HER CHANGE A DIAPER”: THE PRIVATE BABY MOMENT THAT…

End of content

No more pages to load