Caught Between Orders, Snow, and Suspicion: How Exhausted GIs Defied Their Marching Schedule, a Furious Internal Debate, and a Killing Blizzard to Carry German Women Prisoners Instead of Leaving Them to Freeze in a Whiteout

The snow started as dust.

Tiny flecks, barely visible, drifting sideways across the road like ash from a fire. By the time the column left the village, it had thickened into a gray curtain that turned the world into layers of smudge and shadow.

“Keep it moving!” Sergeant Tom Daley shouted, blowing into his cupped hands before clapping them together for emphasis. His breath turned white and vanished. “We don’t wanna be on this road when it gets dark!”

Ahead of him, the line of prisoners shuffled into motion.

They were a mix—a handful in threadbare gray-green uniforms, more in worn civilian coats and skirts, scarves pulled tight against the wind. All women, all Germans, all with a narrow strip of white cloth tied around their arms to mark them as POWs. Some carried small bags. Some had nothing at all.

Behind them marched the Americans, boots crunching on the packed snow over frozen mud. Rifles slung, packs digging into shoulders that had already carried too much for too long.

Tom walked along the left side of the column, eyes flicking between the prisoners and the road ahead. The snow had started to stick, whitening the fields on either side, softening the outlines of low stone walls and leafless trees.

“Hey, Sarge!” called Private Eddie Rossi from somewhere in the middle of the line. “You sure this is the right way? Feels like we’re marching straight into the North Pole.”

Tom glanced back at him.

“You see any reindeer?” he said. “No? Then shut up and walk.”

There was a tired ripple of laughter from the men. The prisoners, who understood more English than they admitted, exchanged small, wary looks.

At the very back of the German line, Elsa Vogt tried to pull her scarf higher over her mouth. It was already stiff with frost where her breath had frozen the wool. The wind sliced through her coat as if it were made of tissue paper.

“This is madness,” muttered Ilse, trudging beside her. “They could have left us in the village. The barn was warm.”

“The barn was full of holes,” Elsa said, though her own chest ached with longing for the smell of hay and the dim safety of walls.

Ilse made a face.

“I’d take holes over this road,” she said. “If I fall down here, there is nowhere to hide my bones.”

“They want us away from the front,” said Marta, walking on Elsa’s other side, jaw clenched. “Away from their supply lines. Away from… everything.”

“Alive?” Ilse asked, sharp.

Marta hesitated.

“For now,” she said.

Elsa looked ahead.

Somewhere beyond the curtain of snow was another camp. Another set of fences. Another sign that their world had shrunk to marching and waiting. But the sergeant had said it was “safer” there. Farther from artillery, from angry civilians.

He hadn’t said anything about blizzards.

“Eyes front!” Tom barked at the column, more from habit than necessity. “Quit rubberneckin’. The road ain’t gonna get prettier if you stare at it.”

He adjusted the strap of his rifle and squinted at the sky. The clouds were low, heavy, the light already fading though it was barely afternoon.

Lieutenant Harris slogged up beside him, pulling his scarf tighter.

“How we doin’?” Harris asked, blowing into his hands.

Tom nodded toward the prisoners.

“Slow,” he said. “But still walking.”

Harris studied the stumbling line.

“I don’t like this,” he said. “Weather’s closing in. We push too slow, we’re campin’ in the open. We push too fast…” He let the sentence trail off.

Tom knew how it ended.

They’d been given orders: move the prisoners from the village to the rear holding camp, ten miles west. The trucks had been pulled for fuel elsewhere. The jeep was for the officers and the radio. Everyone else walked.

“Regiment said storm wouldn’t hit till tonight,” Tom said. “Regiment was wrong.”

“Regiment’s safe in a stone house right now,” Harris muttered. “We’re the ones out here makin’ their plan work.”

Tom didn’t argue.

He glanced at the prisoners again.

Most were still moving with the stiff, careful steps of tired people trying not to slip. But a few already lagged, their movements jerky, shoulders hunched.

“If it gets bad,” Harris said quietly, “we can’t afford to carry anyone. You know that.”

Tom’s jaw worked.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

An hour later, the snow was no longer dust.

It came down in thick, heavy flakes, blown sideways by a wind that found every gap between scarf and collar. The road disappeared under a fresh layer, hiding the ruts that could twist an ankle or send a boot sliding.

Visibility shrank. The village behind them vanished in the white. The woods ahead became smudged shapes, then vague suggestions.

“Close it up!” Tom shouted. “Nobody wander! You can’t see the man in front of you, you’re too far back!”

Elsa’s world narrowed to the patch of ground just ahead of her boots and the shape of Ilse’s shoulder beside her.

“Can you see them?” she gasped.

“See what?” Ilse’s teeth chattered.

“The… Americans,” Elsa said. “If they go, we… fall.”

“They’ll leave us to freeze,” Ilse said bluntly. “You think they will die for us?”

“They told us they were… civilized,” Elsa said.

Marta snorted.

“Civilized has a temperature,” she said. “This is beyond it.”

Behind them, one of the Americans cursed as he slid, catching himself on his rifle.

“Watch your step!” another yelled. “We lose somebody in this mess, we’re not findin’ ‘em again till spring!”

Tom trudged along the flank of the column, boots sunk to the laces, snow working its way down inside his socks. His fingers had gone from aching to clumsy to a worrying lack of feeling.

“Daley!” came Harris’s voice from up ahead. “Front!”

Tom shoved his way through the line, muttering, “Make a hole,” until he reached the lieutenant near the head of the column.

Figures loomed through the snow—two American soldiers from the lead squad, faces coated in white, scarves rimed with ice.

“Road ahead’s drifted in,” one of them said. “Knee-deep at least. Can’t see where it starts. Trees on both sides.”

Harris swore softly.

“We’re not getting through that before dark,” he said.

Tom looked at the prisoners.

They were packed close now, breath steaming, eyes wide and ringed with frost. One woman near the front had blood on her stocking, a rip just above her boot where she’d stumbled over something hidden under the snow.

He looked at the American line.

The men were tired. Their faces had that gray, pinched look he recognized from the winter in the Ardennes—when the cold had been an enemy all its own.

“Options?” Harris asked.

“Turn back?” one of the soldiers offered half-heartedly.

“To what?” Harris said. “Village is five miles behind us. Camp is five miles ahead. We’re in the middle of nowhere.”

“We could bivouac in those trees,” Tom said, nodding toward the blurred shapes. “Get some shelter from the wind. Dig in.”

“And freeze slow,” Harris said. “We don’t have tents. Barely enough blankets for our own men.”

Silence.

Tom could feel the weight of the decision pressing down on them like the snow.

Regimental orders had been clear: move the prisoners, no delays, no stragglers. This road was supposed to be simple. Except weather didn’t give a damn about typewritten orders.

“We push on,” Harris said finally. “Take it slow through the drifts. Keep ‘em moving. If they stop, they freeze.”

“And if they can’t move?” Tom asked.

Harris didn’t answer right away.

“We keep the column moving,” he said at last. “We can’t get stuck out here.”

Tom swallowed.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

The snowdrift appeared like a white hill in the middle of the road.

It rose as they approached, deeper and deeper, until the first step into it sent snow up over boot tops, then halfway to knees.

“Lift your feet!” somebody yelled. “Don’t shuffle! High steps!”

The Americans, laden but stronger, powered through, grunting with effort. The prisoners struggled.

Elsa lifted her foot, the snow sucking at it like wet cement. She set it down ahead, then tried to move the other.

It didn’t want to come.

“What are we walking in?” Ilse gasped. “Clouds?”

Marta stumbled, catching herself on Elsa’s arm.

“I can’t…” she began.

“Keep moving!” came the inevitable shout from somewhere behind. “Don’t stop! You stop, you’re stuck!”

Elsa pulled her foot free again, heart thudding.

All along the line, women started to falter. A few let out panicked cries as they sank deeper, snow filling their boots, numbing their calves.

“Move, move, move!” Tom shouted, pushing into the drift from the side, snow soaking his pants instantly. “Get through this and it’s easier on the other side!”

He hoped that was true.

Private Rossi slogged along behind a cluster of prisoners, breath ragged.

“Jesus,” he wheezed. “This is worse than basic.”

“Least in basic nobody shot at us,” muttered the guy behind him.

No one mentioned that the snow was a different kind of bullet.

A woman near Rossi’s left stumbled. She went down hard, a small, muffled cry cut off as the snow swallowed half her body.

“Get up!” Rossi yelled instinctively. “Come on!”

She struggled, arms flailing weakly, hands encased in clumsy mittens.

Her eyes were wide, whites stark against her windburned face.

“Bitte,” she gasped. “Bitte…”

Rossi reached toward her without thinking.

“Leave her!” someone shouted.

He froze.

Sergeant Daniels, a lean, hard-faced man from another squad, grabbed his arm.

“Don’t you dare,” Daniels snapped. “You go in after her, we’re pullin’ out two bodies instead of one. Keep movin’!”

“She’s stuck!” Rossi protested. “She’ll—”

“She’ll slow the column,” Daniels said. “We’re not a goddamn rescue squad for every prisoner who missteps. Orders were clear: no stragglers, no stoppin’. You wanna freeze out here because you played knight in shiny armor?”

Tom, hearing the raised voices, slogged through to them.

“What’s goin’ on?” he demanded.

Rossi gestured helplessly toward the woman.

She was halfway upright now, but her legs were still buried. The snow had packed around them like concrete.

Her lips were turning blue.

“They’re leaving us,” Ilse hissed in German from somewhere nearby. “I told you. They’ll leave us to freeze.”

Elsa’s chest clenched.

“Sergeant,” Rossi said, turning to Tom. “We gotta pull her out.”

Daniels shook his head.

“We gotta keep movin’,” he said. “You start haulin’ prisoners outta drifts, the whole column stops. You think the lieutenant’s gonna explain to Regiment that his men froze because they tried to save enemy personnel from bad footing?”

Tom looked at the woman. Saw the terror in her eyes. Saw, too, the line of prisoners backing up behind her, the Americans stumbling, the drift stretching ahead like a white wall. Snow still fell, thick and relentless.

He looked at Daniels.

“Orders are orders,” Daniels said. “You know that.”

Tom’s jaw tightened.

He thought of that winter in the Ardennes, when a lieutenant had told his squad to leave a wounded comrade behind because they couldn’t carry him and keep pace. Tom had disobeyed then. They’d carried the man anyway. Caught hell for it later.

The man had sent him a letter from hospital months after.

He thought of the orders now: move the prisoners, don’t lose any, don’t get stuck.

Orders written in ink in a warm room where the snow was just a symbol on a map.

The woman was shivering so hard he could see it through her coat.

He stepped sideways, knees almost buckling in the deeper drift, and thrust his hands under her arms.

She flinched.

“Hold still,” he snapped. “I’m not gonna drop you.”

“Sergeant—” Daniels began.

“Rossi!” Tom barked. “Get her legs loose!”

Rossi plunged his gloved hands into the snow around her legs, scooping furiously.

“Daley,” Daniels said, voice low. “You’re makin’ a mistake.”

“Noted,” Tom said. “You can carve it on my frozen backside later.”

Rossi cleared enough snow that the woman could pull one leg out with a gasp. Her boot came free with a sucking sound.

“Other one!” Tom grunted.

They repeated the process. Snow flew. Tom’s arms burned from gripping her under the arms.

“She’s up!” Rossi shouted.

Tom pushed, hauling her upright.

Her legs buckled immediately.

She would go right back down, he realized, if he let go.

“Can you walk?” he asked in German.

She shook her head, teeth chattering too hard for words.

“Then we carry,” he muttered.

He shifted, crouched, turned his back to her.

“Rossi, put her arms ‘round my neck,” he ordered. “Careful not to choke me.”

Rossi’s eyebrows shot up.

“You sure about this?” he asked.

“For the next thirty seconds, yes,” Tom said. “After that, we’ll see.”

They got her onto his back, arms hooked around his shoulders, legs hanging.

She weighed almost nothing.

Too little.

“Daley!” Harris’s voice cut through the wind. “What the hell are you doing?”

Tom straightened as much as he could under the extra weight.

“Keep movin’!” he shouted back. “I’ll catch up!”

“You’ll do no such thing!” Harris snapped, slogging toward them through the drift. “We cannot carry prisoners, Sergeant! We can barely carry ourselves!”

“We leave her, she dies,” Tom said between clenched teeth.

“And if you fall with her?” Harris shot back. “Then what? I lose a prisoner and my best sergeant. That’s not a trade I’m willin’ to make.”

The woman’s breath was hot and shallow against Tom’s neck.

He felt Daniels’ eyes on him, waiting for him to back down. Waiting for him to admit that the math of survival didn’t include this one small person.

Rossi shifted, ready to help if Tom gave the order.

The snow hammered around them, relentless.

“We keep movin’,” Daniels said. “Or we die here. That simple.”

For a moment, Tom wished he believed that.

Then he remembered the letter from the man they’d carried in the Ardennes.

He looked at Harris.

“With respect, sir,” he said, voice steady despite the burning in his legs, “if we walk past her, every man in this column is gonna be thinkin’ about it tonight. And the night after. And the one after that. You really want that kind of ghost in their heads?”

Harris’s jaw clenched.

“You’re makin’ this about feelings,” he said. “This is about gettin’ everybody through alive.”

“Everybody,” Tom said. “She’s included in that. She’s our responsibility. They’re our prisoners, not our… snow decorations.”

A flicker passed across Harris’s face.

“You think Regiment’s gonna see it that way?” he asked.

“No, sir,” Tom said. “I think Regiment’s gonna be mad either way. I’d rather they be mad that I slowed the column than mad that I let someone freeze with a line of armed men marchin’ past her.”

The prisoner on his back made a small sound.

Harris closed his eyes briefly, then opened them.

“Fine,” he said. “One. You carry one. Rossi, you help another if she goes down. Daniels, you and your men keep these lines tight. No stoppin’ unless someone is literally buried.”

“Yes, sir,” Daniels said stiffly.

“And Daley,” Harris added, voice at half-snarl, half-sigh. “If you go down with her, I am not sending half the platoon in after you. You understand?”

Tom nodded.

“I understand,” he said.

Harris jabbed a finger toward the drift.

“Move,” he snapped. “Before we all become popsicles.”

The column lurched forward again.

The woman’s weight dug into Tom’s shoulders. His thighs screamed with each high step through the snow. The wind slapped his face raw.

“You okay up there?” Rossi asked, slogging beside him.

“Ask me in five minutes,” Tom panted.

Behind them, Daniels muttered curses that steamed in the air.

“Idiot,” he said under his breath. “Goddamn noble idiot.”

Elsa watched the scene from a few bodies back, heart thudding.

“He’s carryin’ her,” Ilse whispered in German. “He’s actually carryin’ her.”

“They will leave us to freeze,” Marta repeated softly, but her voice had lost some of its certainty.

Elsa didn’t know the American sergeant’s name, only his voice. But she watched him take step after step with the woman on his back and felt something unfamiliar prick at her chest.

Hope, murmured a traitorous part of her mind.

“Keep movin’!” Tom shouted, more to himself than anyone. “This drift ain’t gonna own us!”

By the time they cleared the worst of the drift, Tom’s legs felt like they’d been replaced with sacks of wet sand.

“Down,” he croaked to Rossi. “Gotta… set her down.”

They eased the woman off his back onto a relatively firm patch of snow just past the drift. She sat heavily, chest heaving.

Her face was pale but less blue.

“You alive?” Tom asked in German.

She nodded shakily.

“Danke,” she whispered. “Thank you.”

“Don’t make it a habit,” he muttered. “We can’t carry the whole camp.”

He looked back.

Another woman had gone down in the drift, but Rossi was already hauling her up by one arm, grunting, “Come on, lady, I only got one back. Daley got the other.”

Harris slogged past, eyes scanning the line, jaw still tight but no longer set in absolute refusal.

Daniels passed too, his gaze catching on the prisoner Tom had carried. He snorted.

“Congratulations,” he said. “You saved one. Hope you enjoy the chewing-out later.”

Tom shrugged, chest still burning.

“I’ve had worse,” he said. “From you.”

Daniels almost smiled.

“Shut up and walk,” he said.

The words sounded less harsh than usual.

They made it into the trees just as the light went gray-green with dusk.

The woods weren’t thick—thin trunks and bare branches—but they broke the wind. The snow here was patchier, trapped in hollows and drifts but not an endless sheet.

Harris called a halt.

“Five minutes!” he shouted. “Catch your breath, but don’t sit all the way down! You sit, you stiffen, you’re not gettin’ up!”

The men leaned against trees, bent double, wheezed.

The women prisoners clustered together, some crying quietly, some just staring, lashes crusted with ice.

Elsa sank onto a stump, ignoring Harris’s warning.

Her legs trembled violently. She wasn’t sure she could stand again even if someone offered her a gold ring for each step.

“We’re not dead,” Ilse said, almost in disbelief.

“Not yet,” Marta said.

The woman Tom had carried sat on a fallen log, arms wrapped around herself. One of the American medics knelt at her feet, checking her toes for signs of frostbite, talking to her in slow German.

Tom leaned against a tree, eyes closed, breath fogging the bark.

Rossi slumped beside him.

“You’re crazy,” Rossi said. “You know that?”

“Probably,” Tom replied.

“You’re also gonna be limpin’ tomorrow,” Rossi added.

“I’m limping now,” Tom said.

Harris approached, pushing his scarf down.

“Sergeant,” he said.

Tom straightened, wincing.

“Yes, sir.”

Harris looked at him for a long moment.

“You disobeyed the spirit of my orders back there,” he said. “You slowed the column, you put yourself at risk. And you made me look like I don’t know how to control my NCOs.”

“Yes, sir,” Tom said.

“You also probably kept that woman from dyin’ in a snowdrift,” Harris said. “And I’m not in a hurry to explain to Corps why we left bodies on the road after they told us to deliver prisoners alive.”

Tom blinked.

“So,” Harris continued, “consider yourself chewed out for takin’ initiative I didn’t explicitly authorize. Then consider yourself quietly… not punished.”

“Yes, sir,” Tom said cautiously.

Harris’s mouth twitched.

“Don’t make a habit of it,” Harris said. “We can’t carry them all. But if there’s a next time… use your judgment. You seem to have some.”

He turned to go, then paused.

“And Sergeant,” he added, without making eye contact, “for what it’s worth… if I’d been the one closest to her, I probably would’ve done the same thing.”

Tom stared at his back as he walked away.

“See?” Rossi muttered. “You’re contagious. Next thing you know, Daniels’ll be handin’ out blankets.”

“Don’t jinx it,” Tom said.

They reached the camp after dark, boots dragging, breath coming in ragged clouds.

The gates loomed out of the snow like the edge of the world. A guard shouted. Lights flickered on in low buildings. The smell of wood smoke and something cooking drifted through the air.

It smelled like heaven.

“Move ‘em inside!” Harris ordered. “Get the prisoners into the barracks! No wanderin’, no rest stops! Medics, check anyone who looks like they might pass out!”

Elsa stumbled through the gate, numb with cold and exhaustion.

She was dimly aware of the Americans counting them, of the interpreter barking, “Hurry, hurry!” of the crunch of boots on the hard-packed snow of the camp yard.

Inside the barrack, the air felt thick and warm, though in other times she might have called it chilly.

Women collapsed onto bunks, slipped off boots with shaking hands, hissed as blood returned to their feet.

Elsa let Ilse push her onto the lower bunk.

She lay back, closing her eyes, the world tilting.

“We’re not dead,” Ilse said again, as if saying it could make it more true.

“No,” Elsa murmured. “Not dead.”

“Not frozen,” Marta added. “Not left.”

Elsa opened her eyes.

On the far side of the barrack, the woman the sergeant had carried sat on her bunk, boots off, feet wrapped in bandages. The American medic had left a small tin of ointment on the crate beside her. She touched it as if it were made of glass.

“They carried her,” whispered someone nearby. “Like a child.”

“They didn’t have to,” another said. “They could have left her.”

“They told us they would leave us,” Ilse said. “They didn’t.”

Greta, sitting on her bunk, gave a dismissive snort.

“Do not make saints of them,” she said. “They followed their conscience once. That does not erase everything else.”

“Maybe not,” Elsa said quietly. “But it puts a crack in what we were told.”

Greta’s eyes narrowed.

“Cracks let in cold,” she said.

“Also light,” Klara muttered from the bunk above.

Years later, when the war was a memory rearranged by time, Elsa would try to explain it to her daughter.

They would be sitting at a small kitchen table in a small apartment in a city that had rebuilt itself around its scars. The radio would play some new music that made no sense to Elsa’s ears. The air would smell of coffee and laundry soap.

Her daughter, fifteen and impatient, would have just flung her math book down on the table and said, “Why do we have to learn about all this old stuff? Rivers and dates and battles. It’s over. It doesn’t matter.”

Elsa would look at her for a long moment.

Then she would say, “I used to think that too. That once something was over, it went away. But it doesn’t. It stays in you. Like… like cold in your bones after a winter.”

She would tell her daughter about the march in the snow.

About the village they’d left. About the road that had disappeared. About the drift that had almost swallowed them.

“But they didn’t leave you,” her daughter would say, brow furrowing. “The American carried that woman. You. You said.”

“Yes,” Elsa would say. “He did. One man. One woman. A decision in a snowstorm.”

“And?” the girl would ask. “What does that change?”

Elsa would smile sadly.

“For me?” she’d say. “It changed the shape of the enemy in my head. They stopped being a wall. They became… individuals. Some rough, some kind, some tired. Like us. It didn’t excuse what they did. But it made it harder to believe the simple stories.”

Her daughter would spin her pencil on the table.

“So we remember,” she’d say, “that not everyone leaves people to freeze?”

“Yes,” Elsa would say. “And we remember, too, that sometimes the orders say ‘leave them’ and people decide otherwise. That is important.”

Her daughter would look skeptical.

“You think one sergeant in a storm matters?” she’d ask.

Elsa would think of Tom’s voice shouting through the snow, of the burning in his legs, of the woman on his back barely weighing anything and everything at the same time.

“I think,” she’d say slowly, “that history is a long road. And what keeps it from going completely wrong are very small choices made by very tired people at very bad moments.”

Her daughter would roll her eyes, but not unkindly.

“You and your stories,” she’d say.

Elsa would reach across the table and squeeze her hand.

“When someone is shivering next to you,” she’d say, “I hope you remember them.”

“Remember who?” her daughter would ask.

“The person who didn’t leave someone to freeze,” Elsa would say. “And the part of you that knows you shouldn’t either.”

On the other side of the ocean, in a house with a porch and a maple tree in the yard, an old man named Tom Daley would sit in a faded armchair and watch snow fall outside his window.

His grandson would press his nose against the glass.

“Grandpa,” the boy would say, “did you fight in the war?”

“Yeah,” Tom would say. “I did.”

“Did you shoot bad guys?” the boy would ask, eyes wide.

Tom would think of frozen trenches and shattered towns, of bullets and orders and questions.

“Sometimes,” he’d say. “Mostly I walked. And carried things. And yelled at people to keep movin’.”

“That doesn’t sound like a war,” his grandson would say.

Tom would chuckle.

“It does,” he’d reply. “Just not the part they put in the movies.”

The boy would frown at the snow.

“Did you ever get stuck in a blizzard?” he’d ask. “Like this, but bigger?”

Tom would feel a cold in his legs that had nothing to do with the draft under the window.

“Once,” he’d say. “We were movin’ prisoners. Women. Germans. Storm came in faster than the weatherman thought.”

“What did you do?” the boy would ask.

“We walked,” Tom would say. “We pushed through. Some of ‘em started fallin’ in the snow. One got stuck. I picked her up.”

“Why?” the boy would say, genuinely puzzled. “She was the enemy.”

Tom would look at him, see in his face the echo of his own younger self.

“Because,” he’d say slowly, “in that moment, she wasn’t an enemy. She was just a person who was gonna die in a snowdrift if I walked past. And I had to live with myself after the war, not Regiment.”

His grandson would be quiet for a moment.

“Did you get in trouble?” he’d ask.

“Almost,” Tom would say. “But my lieutenant was a decent man. He yelled at me, and then he didn’t.”

The boy would grin.

“I’m gonna carry people too,” he’d say. “If they fall in the snow.”

Tom would smile, his throat tight.

“Good,” he’d say. “Start with your grandma’s groceries. Then see how far you get.”

Outside, the snow would keep falling, covering the scars and the sidewalks in an indifferent white.

Inside, in memory and in stories, a column would keep moving through a winter long past, a sergeant’s back bent under a light weight that had turned out to be heavy with meaning.

They had been afraid the Americans would leave them to freeze.

Some of them didn’t.

THE END

News

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany, the stunned reaction inside German High…

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat into his first major triumph, the shockwaves reached Rommel himself—forcing a private…

The Day the Numbers Broke the Silence

When Patton’s forces stunned the world by capturing 50,000 enemy troops in a single day, the furious reaction from the…

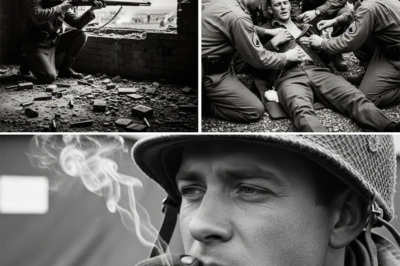

The Sniper Who Questioned Everything

A skilled German sniper expects only hostility when cornered by Allied soldiers—but instead receives unexpected mercy, sparking a profound journey…

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

End of content

No more pages to load