Captured German nurses in the burning African desert braced for a firing squad at dawn—until American soldiers stormed their camp, argued bitterly over the prisoners’ fate, and ended up bandaging the very enemies they’d been trained to fear.

The desert did not care what uniform you wore.

By midafternoon, the North African sun had baked the sand until it shimmered like molten glass. The air trembled above the dunes, turning distant rocks into ghosts and mirages. Flies buzzed around the field station, drawn to blood and sweat and the sweet, sour smell of antiseptic.

Inside the canvas tent marked with a faded red cross, Anna Keller tightened the bandage around a wounded soldier’s leg and tried not to listen to the sounds outside.

Engines.

Shouting.

The distant rumble of artillery like an angry god clearing its throat.

“Too tight?” she asked in German, checking the young man’s face.

He was barely older than she was—twenty-one, maybe twenty-two—with sand crusted in his eyebrows and a gray pallor under the dust on his skin.

“Doesn’t matter,” he rasped. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Anna forced a smile she didn’t feel.

“That’s exactly why it matters,” she said. “If it’s too tight, we fix it. That’s what we do.”

Her voice sounded steady. Her hands, at least, knew what they were doing. They moved on their own now: gauze, knot, check circulation.

In some ways, it was easier to focus on the small circle of a wound than on the huge, collapsing mess of the war around them.

Outside, truck doors slammed. Boots crunched in the gravel. Somebody yelled for more water; another voice answered that there wasn’t any left—not cold, not clean, not enough.

“Anna!” a familiar voice called from outside the tent. “You finished with him?”

She tied off the bandage and patted the young man’s shoulder.

“You’ll be fine,” she lied gently. “Try to rest.”

She stepped out into the glare.

Greta Stein, her fellow nurse and closest friend, stood just outside the tent flap with her hair pulled back under a sweat-stained scarf. Her cheeks were flushed, and there was a streak of dried blood along her sleeve.

“The captain wants to see us,” Greta said. “All of us.”

Anna’s stomach tightened.

“Now?”

“Yes. He says… it’s important.”

They crossed the camp together. It wasn’t much of a hospital—just a cluster of tents around a few battered trucks and a couple of dugouts. The main front had moved miles away, but the wounded kept coming, like waves that hadn’t heard the tide had already turned.

At the center of the camp, Captain Erich Brandt, the medical officer, stood with his hands on his hips. His uniform was wrinkled, his collar open, his face lined with fatigue. Around him, three nurses and a handful of orderlies gathered in a loose semicircle.

Anna recognized Lotte, the youngest nurse, chewing nervously on her lip, and Becker, the orderly who always smelled faintly of cigarettes and car grease.

Captain Brandt looked at them, then at the horizon, where distant plumes of dark smoke rose into the shimmering sky.

“Listen carefully,” he said. “We’ve received orders from command. Our main forces are pulling back. The line is collapsing faster than expected. We don’t have the fuel or escort to keep this station operational.”

Anna’s throat went dry.

“You mean… we’re leaving?” she asked.

Brandt shook his head.

“Some of us are,” he said. “We have room in the trucks for a limited number. The lightly wounded who can walk, the medical records, the essential equipment. The rest…” His gaze slid toward the row of tents where the most seriously injured lay. “We’ve been told to do what we can before we abandon this position.”

The word abandon hung in the air like smoke.

Greta swallowed.

“And the nurses?” she asked. “The staff?”

Brandt looked at her, then at Anna, then at Lotte.

“I suggested we evacuate all medical personnel,” he said slowly. “Headquarters replied that any who stay will… be at the mercy of the enemy.”

He didn’t have to say what that meant. They had heard the speeches, the whispers, the stories. Stories about what happened in captured field hospitals. Stories about “no prisoners” and “no mercy” and “retaliation.”

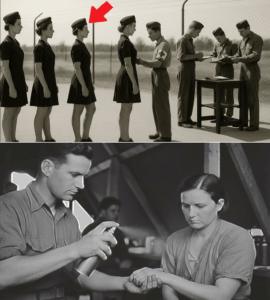

Images flashed through Anna’s mind—grim posters from home, all sharp angles and bold letters, warning what “the Americans” did to captured Germans. In those posters, the enemy never had a face, just a silhouette and a gun.

Now the enemy had a direction: west, where Allied forces were advancing.

“You’re saying we should run,” Becker said, voice rough. “Leave the worst cases to die alone?”

Brandt’s jaw clenched.

“I’m saying those are the orders,” he said. “But I am also saying this: I cannot force any of you. Nurses are valuable. They may… have a better chance if captured. If anyone wishes to leave with the convoy, you can.”

He looked at Anna.

“You can,” he repeated.

She thought of the man she’d just bandaged; of the soldier in bed six whose lungs whistled like broken bellows; of the boy in the back tent who cried out for his mother during fever spikes.

She also thought of the leaflets that had blown into their camp weeks ago—Allied propaganda written in clumsy German, promising fair treatment for prisoners and medical care “for all wounded, regardless of uniform.”

Brandt had burned them in a metal bucket.

“No one believes that,” he had told her as the paper curled and blackened. “Don’t be foolish. They’re not saints. They’re just better at posters.”

Now, faced with the possibility of capture, Anna felt that old fear rise like bile.

Execution.

Worse than execution, some whispered.

She didn’t know what was true and what was paranoia anymore.

But she knew what her hands knew.

“I’m staying,” she said quietly.

Greta looked at her, eyes wide. For a moment, Anna thought her friend would argue. Then Greta nodded.

“Me too,” she said. “Someone has to look after them until… until someone else does.”

Lotte stared at the ground.

“I’m… I’m afraid,” she admitted. “I don’t want to die in a tent.”

Anna reached out and squeezed her hand.

“Then go,” she said softly. “There’s no shame in wanting to live. Go with the convoy.”

Lotte’s eyes filled with tears.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

“Don’t be,” Anna said. “Write to us when the war is over. Tell us you made it.”

Captain Brandt watched, jaw tight.

“The trucks leave in fifteen minutes,” he said. “Decide quickly.”

He turned away, barking orders at the orderlies to prepare the patients for transport. The camp erupted into motion: stretchers being carried, boxes strapped down, canvas flaps tied.

Anna and Greta walked back to the main tent.

“How scared are you?” Greta asked, attempting a shaky smile.

Anna took a breath.

“Very,” she admitted. “You?”

Greta nodded. “Very.”

They shared a look that said everything.

Then they went back to work.

1. Silence after engines

When the trucks finally pulled away, leaving a storm of dust and exhaust fumes, the camp felt wrong.

Too quiet.

Too exposed.

Only the most serious cases remained—men who could not be moved without killing them. There were twelve in total, scattered across two tents. Their breaths filled the hot air with weak exhalations and the occasional groan.

Captain Brandt stayed, despite his rank and the chance to leave.

“I will not walk away from my own patients,” he said simply.

The four of them—Brandt, Anna, Greta, and Becker—moved from bed to bed, checking dressings, offering water, trying to pretend that nothing had changed.

But everything had changed.

The distant rumble of artillery was closer now. Once, an explosion thudded somewhere beyond the hills, setting canvases trembling and bringing a sprinkle of sand down from the tent seams.

“How long do you think we have?” Greta asked as they stepped out to refill a water jug.

Brandt wiped sweat from his brow.

“Hours,” he said. “Maybe less. The fronts move fast here. The Americans have aircraft; if they’ve seen our trucks, they’ve seen our camp.”

“Will they bomb a hospital?” Anna asked quietly.

Brandt glanced at the red cross painted on the tent roofs. The symbol was faded, partially obscured by dust and grime and a year’s worth of sun.

“They shouldn’t,” he said. “The convention says they shouldn’t.”

He didn’t add but conventions are written in cool rooms far from here.

They returned to the tent. Time stretched. Anna changed a bandage, mopped a brow, poured water between cracked lips.

She was standing over the bed of the boy who called for his mother when she heard it: a new sound, slicing through the monotone background of artillery.

Engines.

High. Fast. Angry.

“Planes,” Greta whispered.

Shadows flickered against the tent walls. A second later, the world exploded in noise.

The first bomb didn’t hit the camp. It fell somewhere beyond, sending a shockwave that made the cots tremble. The second one was closer. Canvas snapped in the air like a slapped sail. Dust billowed down from the tent ceiling.

Captain Brandt burst into the main tent.

“Get down!” he shouted. “Everyone down!”

Anna threw herself over the boy’s fragile body as another blast hit—this one close enough to make her ears ring and her teeth ache. She tasted sand and smoke.

Somewhere outside, a truck—or what was left of one—burned, its fuel turning into a black pillar of smoke.

The bombing run was over almost as soon as it began. A minute of terror, then the receding snarl of engines as the planes moved on in search of bigger targets.

Anna pushed herself up, ears still buzzing.

Greta coughed, waving away dust.

“Everyone alive?” Brandt called, voice hoarse.

“I think so,” Becker answered from the other tent.

The boy under Anna’s arms blinked, dazed.

“Did… did it hit us?” he whispered.

“Not directly,” Anna said, helping him settle back. “We’re still here.”

She stepped outside to assess the damage.

The camp was a mess. One of the smaller supply tents had been shredded, its canvas hanging in ribbons. A crater smoked just beyond the perimeter. One of the water barrels had split, sending precious liquid gushing into the sand, where it vanished instantly.

Anna stared at the spreading dark patch.

“Well,” Greta said softly, standing beside her. “There goes our drinking water.”

As if to underline the point, the sun seemed to press harder on their shoulders.

Brandt joined them, coughing.

“We can’t stay out in the open like this,” he said. “If the front moves through here, we’ll be caught in the middle of a battlefield.”

“What choice do we have?” Greta asked. “The patients can’t walk.”

Brandt’s gaze swept the landscape. The camp sat in a shallow depression, surrounded by low, rocky rises.

“There’s a dry riverbed—wadi—just beyond that ridge,” he said, pointing. “Some shade, at least. Maybe some cover if vehicles come through.”

He looked at Anna and Greta.

“We move who we can. The ones with head wounds, chest wounds… they stay. Moving them would kill them faster.”

Anna’s stomach knotted.

“You’re saying we choose who gets a chance,” she said.

He met her gaze steadily.

“I’m saying we choose who has any chance,” he replied. “If the enemy comes, those who can’t move will be prisoners—or worse—no matter what we do. But if we sit here, all of us may be caught in fire.”

He didn’t raise his voice, but Anna could feel the fight building inside her.

“And what if they do execute prisoners?” she demanded. “You’ve heard the stories. You burned their leaflets yourself. Are you so sure they’ll treat captured staff well?”

“I’m not sure of anything,” he said. “Except that staying here guarantees nothing but dehydration and a slow death when the water runs out.”

Greta stepped between them.

“Please,” she said. “Not now.”

But it was too late; và cuộc tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng…

The argument had become serious and tense, fueled by fear instead of logic, exhaustion instead of reason.

“For months you told us the enemy would never spare us,” Anna said. “Now you want us to trust them with our patients?”

“I want you to trust that doing nothing is not an option,” Brandt snapped. “We can debate morality when we’re not standing in a drying puddle that was our last water barrel.”

Silence fell, thick and hot.

Finally, Anna looked away.

“Fine,” she said. “We’ll move who we can. But I’m not leaving anyone alone to die.”

“Neither am I,” Brandt said, some of the heat bleeding from his voice. “We do this together.”

They set to work.

2. Into the wadi

Moving wounded men without stretchers is slow torture—for the carriers and for the patients.

They fashioned makeshift litters from tent poles and canvas. Becker lashed them together with strips of rope and torn fabric, his fingers moving with desperate efficiency.

Anna and Greta lifted and carried, step by careful step, stumbling over rocks, trying to keep the patients as level as possible.

Each time a man groaned or hissed in pain, Anna muttered apologies under her breath.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry, just a little further.”

The wadi was shallow but blessedly shaded, at least in parts, by scraggly bushes and a few bent trees clinging to life. The dry riverbed offered some concealment from the open desert, its steep sides like a crumbling embrace.

They made three trips.

By the end of the third, Anna’s arms felt like they were made of lead. Sweat soaked her uniform. Her head throbbed.

They had moved eight of the twelve patients—those whose wounds were serious but not immediately fatal. The four with severe internal injuries and head trauma remained in the tents, lying in the quiet aftermath of the bombing.

“What about them?” Anna asked, wiping her forehead with the back of her hand as they stood in the wadi.

Brandt looked up toward the ridge, where the camp lay hidden from view.

“We’ll go back,” he said. “One of us should stay there. If the Americans arrive, they will see the red cross. They may bring their own medics.”

“You don’t know that,” Greta said.

“No,” he agreed. “I don’t. But leaving wounded alone in tents feels worse than staying with them and… seeing what happens.”

“I’ll go,” Anna said.

Brandt shook his head.

“I should—”

“You’re the doctor,” she cut in. “These men here need you more than the ones who might not live long enough to be captured. Greta can help you. Becker too.”

Greta opened her mouth to protest, then closed it again, seeing the look in Anna’s eyes.

“I’ll come back later,” Anna said. “If I can.”

Brandt studied her for a long moment.

“You’re stubborn,” he said. “You know that?”

“I’ve been told,” she replied.

He nodded, acceptance in his eyes.

“All right,” he said. “Take a canteen. If you see vehicles, stay visible enough that they see the cross, but not so close you’re run over.”

“Comforting,” Anna muttered, taking the canteen.

She climbed out of the wadi, boots slipping in loose sand, and made her way back toward the skeletal remains of the camp.

3. The first sight of the enemy

By the time Anna reached the camp again, the sun had begun its slow descent, turning the sky a harsher white instead of pure, blinding glare.

The air felt different now. Charged.

She moved between the tents, checking on the four men left behind. Two were unconscious. One stared at the tent ceiling, eyes glassy. The fourth—a corporal with a bandaged head—grabbed her hand as she passed.

“Are they gone?” he asked. “The others?”

“For now,” she said. “We moved some into a dry riverbed. More shade.”

He chuckled weakly.

“Always liked rivers,” he murmured. “Even dry ones.”

She stayed with them as the minutes stretched. The canteen grew lighter. The heat pressed down.

Then, in the distance, she heard it: a new sound that wasn’t artillery or planes.

Engines.

Multiple.

Approaching.

Anna stepped out of the tent, heart pounding.

On the western horizon, a thin line of dust rose. Shapes emerged from the haze—vehicles, low and square. She could see the sunlight flashing off windshields, the silhouettes of turret-mounted guns.

Trucks. A couple of armored cars. A half-track.

They rolled toward the camp like a slow, inevitable tide.

Anna’s training told her to show the red cross, to wave a cloth, to signal that this was a medical station. Her fear told her to hide.

She chose training.

She grabbed a length of canvas with a red cross from the side of the tent and stepped out into the open, raising it high above her head.

Her hands trembled, but she held the cloth steady.

The lead vehicle slowed. A horn blared once, sharp and short. The convoy ground to a halt just beyond the edge of the camp, engines idling.

For a moment, everything was eerily still.

Then doors opened. Men climbed down.

They wore uniforms the color of dust and sun-bleached earth, different from the gray she knew. Helmets with nets instead of smooth steel. Boots caked with the same sand, but a different purpose.

They carried rifles, but not like parade props the way some German troops did. These weapons seemed like extensions of their bodies—worn, familiar, ready.

One of the men barked something in English.

Anna didn’t understand all the words. She caught “hands,” “up,” “don’t move.”

She dropped the cross cloth and slowly raised her hands.

Her mouth was dry as ash.

This is it, she thought. This is where it ends.

She thought of posters, leaflets, whispered warnings in the barracks. She pictured herself lined up against a tent, a squad of rifles in front of her.

She tried to slow her breathing and failed.

More men fanned out around the camp, weapons scanning, eyes sharp. One approached her cautiously, rifle held at an angle.

He was in his late twenties, maybe early thirties, with a strong jaw and dark hair cropped short. His eyes were a curious gray-blue, narrowed against the sun.

He spoke, slower this time.

“Are you alone?” he asked in accented German.

The words startled her.

“You… speak German,” she managed.

“A little,” he said. “Enough for this.”

He jerked his chin toward the tents.

“Soldiers? Weapons?”

“Wounded,” she said quickly. “Only wounded. We’re a field hospital.”

“You?” he asked, nodding at her uniform. “Nurse?”

She nodded.

“Yes. Nurse Anna Keller. German Red Cross.”

He hesitated.

“You have any… guns?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “Just bandages.”

He studied her for a moment longer, then signaled to someone behind him.

“Doc!” he called in English. “You’re gonna want to see this.”

A second man approached—slimmer, wearing a different insignia on his sleeve. His helmet was pushed back slightly, revealing a sweaty brow and a pair of tired eyes that still managed to look gentle.

He carried a medical bag.

He took in the tents, the painted crosses, the wounded shapes inside.

“Field station,” he said in English. “German. Looks like they got left behind.”

“Orders?” the first man asked.

The newcomer looked at Anna, really looked at her. She sensed, even through the language barrier, that he was weighing something.

“First order,” he said. “Nobody shoots anybody in a tent with a red cross on it.”

He turned and shouted: “Weapons low! We’re in a hospital, not a firing range!”

The soldiers shifted, lowering their rifles a fraction, though not enough to be relaxed.

He switched to halting German.

“I am Captain Daniel Harris,” he said. “United States Army Medical Corps. We… treat wounded. That includes yours.”

Anna blinked, thrown off balance.

“You… what?” she asked.

He struggled for words, then lapsed back into English, speaking to the first soldier.

“They’re expecting us to line them up,” he muttered. “You can see it in their faces.”

The other man—who Anna would later learn was Lieutenant Jack Monroe—snorted softly.

“Yeah, well, maybe don’t say ‘prisoner’ and ‘processing’ in the same sentence,” he replied.

Harris shook his head.

“Get the men to secure the area,” he said. “No shooting unless someone actually aims at us. I’m going in there before half these guys bleed out.”

He glanced at Anna again and, in careful German, added:

“You help?”

She nodded, because she didn’t know what else to do.

4. The argument over the wounded

The American soldiers moved through the camp in a disciplined, wary pattern. Some checked the surrounding dunes with binoculars. Others peered into tents, calling out updates.

“Multiple casualties,” someone reported. “Mostly German uniforms. Minimal equipment. No heavy weapons.”

A third voice—deeper, rougher—answered.

“So this is a field hospital,” it said. “Great. Just what we needed.”

Sergeant Tom Hardin stepped into the main tent with his rifle slung across his chest. He was older than most of the men, with a permanent sunburn and lines etched into his forehead.

He took one sweeping look at the rows of beds and the German uniforms, then zeroed in on Anna and Captain Harris kneeling over a wounded soldier.

Harris had his sleeves rolled up, his hands already inside the edges of a bandage, checking for bleeding.

“What are you doing, Doc?” Hardin demanded.

Harris didn’t look up.

“What does it look like?” he said. “I’m making sure this man doesn’t die in the next five minutes.”

Hardin stepped closer.

“That ‘man’ is wearing gray,” he said. “In case you missed it. We’re not in Kansas. These are the folks trying to kill us.”

Harris finally looked up, irritation flashing in his eyes.

“He’s also wearing a lot of blood,” he said. “And we’re medics. We treat wounds. That’s the job.”

Hardin’s jaw tightened.

“The job is to keep our men alive,” he snapped. “You want to play charity with the enemy, do it after we’ve secured the area. They could have mines, guns, whatever.”

Anna understood enough English to catch the tone, if not every word. She recognized that tone. She’d heard it in her own camp, aimed at enemy leaflets, prisoners, them.

Lieutenant Monroe stepped into the tent, picking up on the tension instantly.

“What’s going on?” he asked.

“Doc wants to patch up every gray uniform in the room,” Hardin said. “We just rolled into an unsecured camp, and he’s elbow-deep in a German chest.”

“I’m elbow-deep in a chest because that man will drown in his own blood if I’m not,” Harris shot back. “And this ‘German’ you’re so worked up about? He’s not holding a gun. He’s holding onto the last few hours of his life.”

Monroe pinched the bridge of his nose.

“Sergeant, the area is secure,” he said. “We’ve got perimeter watch, and the recon guys say the nearest enemy unit is miles away. Unless these nurses are hiding artillery under their cots—”

He caught himself, glancing briefly at Anna.

“—we’re not under immediate threat.”

Hardin pointed at Anna and the unconscious soldiers around her.

“You know what they would do if this was one of our field hospitals?” he said. “You seen the reports from other fronts? ‘No quarter.’ ‘No survivors.’ They’d roll right over us.”

“Nobody’s rolling over anybody,” Monroe said, voice low.

“Maybe they should,” Hardin muttered.

Harris’s temper snapped.

“Enough,” he said sharply. “We’re not here to copy the worst stories from every front. We’re Americans. We signed the conventions. We treat wounded. That’s what separates us from whoever forgets there’s a line.”

Hardin turned toward him fully, eyes narrowed.

“With respect, Captain,” he said, “my brother’s name is on a cross back in Sicily because people in these uniforms were ‘just doing their job.’ Forgive me if I don’t feel like playing saint today.”

The air between them crackled.

Anna watched them, heart hammering, understanding more than she wanted. She heard the words “brother,” “Sicily,” “cross.” She saw the pain behind the sergeant’s anger—old grief weaponized by fresh fear.

For a moment, she thought Monroe would side with Hardin. It would be easy. Practical. One less moral argument in an already complicated war.

Instead, the lieutenant took a step forward and lowered his voice.

“Tom,” he said. “Listen. You’re not wrong to be angry. You’ve earned it. But we’re not in that foxhole anymore. We’re in a medical tent. The doc knows what he’s doing. And if word gets back that we walked into a field hospital and treated it like a firing range, that stain doesn’t wash off. Not from any of us.”

Hardin opened his mouth, then closed it again. His chest rose and fell.

“So we’re just going to patch them up and send them back to shooting at us?” he asked.

Harris shook his head.

“No,” he said. “We patch them up and send them to a POW camp where they’ll sit behind wire until someone in a better office decides what’s next. We step over them now, we lose more than they do.”

The argument had reached a sharp, fragile edge. One more wrong word and it would shatter.

Hardin’s gaze slid to Anna. She wasn’t sure what he saw—a threat, a victim, something in between.

Finally, he grunted.

“Fine,” he said reluctantly. “You play doctor. I’ll make sure your halo doesn’t get shot off while you’re busy.”

He turned away sharply and strode out of the tent, barking new orders to the men outside.

Monroe exhaled.

“That could’ve gone worse,” he said.

“It still might,” Harris muttered. Then, to Anna, in German: “Ignore him. He is… upset. We have people like that too.”

“We have people like that too,” Anna said quietly, surprising herself by answering in halting English. “On our side.”

Harris blinked.

“You speak English,” he said, in English this time.

“A little,” she replied. “Enough for this.”

He smiled despite the heat and tension.

“Good,” he said. “Then you’ll understand when I say: I need your help if we’re going to keep these men alive. Can you show me who’s worst off?”

Anna hesitated, glancing toward the tent flap where Hardin had disappeared.

“Are we… prisoners?” she asked.

Harris nodded.

“Yes,” he said. “You’re prisoners. But you’re also medical staff. So right now, you’re colleagues. Let’s start there.”

Something unclenched in her chest.

“Then come,” she said. “I’ll show you the head wounds first.”

5. Bandaging enemies

Work has a way of shrinking the world.

Once Harris’s medics joined Anna and Greta, the tent became less a German facility and more a neutral space where blood didn’t care about flags.

They worked as a team—awkwardly at first, then with growing rhythm.

Anna showed Harris where they kept morphine, saline, clean bandages. He showed her how he improvised splints from lengths of aluminum and spare wood. Greta held down a thrashing soldier while an American medic checked his pupils with a small flashlight.

Language fluttered around them in fragments.

“Scalpel.”

“Verbandszeug.”

“Hold here.”

“Fester drücken.”

“Easy, easy…”

At one point, Anna found herself shoulder to shoulder with Harris over a particularly bad leg wound. The man on the cot hissed in pain as they cleaned and re-dressed it.

“This should have been seen two days ago,” Harris said, shaking his head. “You did what you could with what you had.”

“We ran out of better bandages,” Anna said quietly. “We… ran out of a lot of things.”

Harris glanced at her.

“How long have you been out here?” he asked.

“Almost a year,” she said. “Different stations. This one… three months.”

“Why did you stay when your trucks left?” he asked.

She hesitated, then decided there was no point in pretending.

“Because the ones they took might live without me,” she said. “These ones wouldn’t.”

Harris absorbed that in silence.

On the other side of the tent, Greta was showing an American medic where the German doctor kept his notes.

“He writes everything down,” she said, tapping the worn leather notebook. “Temperatures, doses. Even when there is no medicine, he writes what he would have given, if he had it.”

The medic whistled softly.

“Doc back home would like that guy,” he said. “You said he stayed too?”

“Yes,” Greta replied. “He refused to go. Said it would be… cowardly.”

The medic glanced toward the tent entrance.

“So where is he?” he asked.

As if summoned, Captain Brandt appeared, escorted by two American soldiers. His hands were empty, his posture stiff.

“I’m Doctor Brandt,” he said in formal German. “I assume you’re in charge here now.”

Monroe stepped forward.

“I’m Lieutenant Monroe,” he said, gesturing to Harris. “He’s your counterpart. We’re not here to run this as a German field station anymore, but we also don’t plan to leave anyone to die.”

Brandt’s gaze moved over the Americans, the way their uniforms sat, the way their weapons lay just outside the tent flap.

“You will take us as prisoners,” he said.

“Yes,” Monroe replied. “You, your nurses, any support staff. You’ll be part of the POW transfer when it comes through.”

Brandt nodded once.

“And until then?” he asked.

“Until then,” Harris said, “we work together. You know these patients. We have more supplies. Seems foolish to let pride get in the way of stitches.”

Brandt’s lips twitched.

“Pride is what got us into this mess,” he murmured. “It should at least get out of the way while we clean it up.”

He stepped into the tent and rolled up his sleeves.

“All right then, Captain Harris,” he said. “Show me what a United States medical kit looks like.”

6. Waiting for dawn

By the time they had stabilized all twelve patients, the sun was sliding down toward the jagged horizon. The desert changed color—from harsh white to bruised gold, then to deepening rose.

Outside, the American soldiers had set up a temporary perimeter. A radio crackled with coded messages. Somewhere, someone played a harmonica, the notes thin and oddly cheerful in the cooling air.

Anna, exhausted, sat on an overturned crate just outside the main tent. The canteen Harris had given her was half-empty now. The water tasted like metal and hope.

Greta sank down beside her, stretching her aching legs.

“Do you still think they’re going to shoot us?” Greta asked quietly.

Anna watched a pair of American soldiers share a cigarette near the truck, their silhouettes dark against the setting sun.

“I don’t know what I think,” she said. “I thought they would. I thought they’d see our uniforms and… decide.”

She rubbed her sore hands together.

“Instead, their medic cursed at their sergeant and made him lower his gun so he could help our patients,” she said. “I didn’t expect that.”

Greta smiled tiredly.

“I didn’t expect coffee,” she said.

Anna blinked.

“Coffee?”

Greta nodded toward the tent behind them.

“One of the medics brought me a cup while we were working,” she said. “It was terrible, but it was hot. I almost cried.”

Anna laughed weakly.

“You probably scared him,” she said.

Greta’s smile faded.

“What happens now?” she asked. “We’re their prisoners. Where do they take us?”

Anna shook her head.

“Camp, I suppose,” she said. “Wire, guards. Maybe ships. You heard them—they talked about transport.”

Greta’s eyes glistened in the fading light.

“At least we’re not lying in the sand,” she said. “Captain Brandt said once that in this war, sometimes survival is just a series of small, lucky accidents.”

“Do you think this is an accident?” Anna asked.

Greta considered.

“No,” she said. “I think this is a choice. That medic chose not to be what we were told he was. The sergeant chose not to push it. Our doctor chose to stay. You chose to stay. Maybe that’s all we have left—little choices that add up to something.”

They sat in companionable silence for a moment.

Footsteps approached.

Anna looked up to see Sergeant Hardin standing a few paces away, hands on his hips. He looked different in the half-light—not softer, exactly, but less sharp.

“Red Cross,” he said, nodding at the patch on Anna’s sleeve. “You girls been at this long?”

“‘Girls’ have names,” Anna replied before she could stop herself. “Anna and Greta.”

Hardin’s mouth twitched.

“Fair enough,” he said. “Anna and Greta. Been nursing long?”

“Three years,” Anna said. “Two in training, one out here. You?”

He snorted.

“Long enough,” he said. “Drafted at twenty-two. Been playing soldier ever since.”

He scratched the back of his neck.

“Look,” he said, eyes flicking away then back. “About earlier. When I… made a scene in there.”

“A scene?” Greta repeated with a small smile. “That’s one word for it.”

Hardin sighed.

“I lost my temper,” he said. “Doc’s right. We signed some papers. We’re supposed to be the good guys. Sometimes I forget there’s a difference between what happened to me and what I should do now.”

Anna studied him.

“Your brother?” she ventured, recalling the word she’d understood.

He nodded once.

“North of here,” he said. “Different front. Different uniforms. Same mess. I got the letter just before we shipped out. Haven’t… really figured out what to do with that yet.”

“I’m sorry,” Anna said quietly.

He shrugged, as if that topic weighed too much to handle.

“I’m not here to make you feel better about America,” he said. “Don’t go telling your people we’re saints. We’re not. We screw up. We get ugly. I’ve seen guys do things I’m not proud to be near.”

He looked toward the tents.

“But today,” he said, “we didn’t shoot the folks in the field hospital. That’s… something.”

“It’s more than some would have done,” Anna said.

He managed a thin smile.

“Don’t give us too much credit,” he said. “Half the guys out there are just glad we didn’t add paperwork to our day. You die, that’s a whole extra form.”

Greta snorted, surprising herself.

Hardin’s gaze softened.

“You’ll be moved in the morning,” he said. “POW transport. You’ll get a tag, a number, and bad coffee. Could be worse.”

He hesitated, then added:

“And… you did good work in there. Your patients are lucky you stayed.”

Anna felt a lump in her throat.

“Thank you,” she said.

He nodded awkwardly and walked away, as if afraid staying any longer might cause his hardened exterior to crack.

7. The camp

They spent the night under guard but not under threat.

American soldiers posted near the tents, rifles slung but not pointed. A fire crackled near the center of the camp. Someone passed around tin cans of beans. An extra portion found its way to Anna and Greta via a sheepish young private who spoke no German but pointed at his mouth and mimed eating with exaggerated chomps.

“Thank you,” Anna said in English. “For the… beans.”

He grinned and made a thumbs-up gesture.

In the early hours before dawn, Anna walked once more among the beds. Most of the wounded slept, aided by morphine and exhaustion. One stirred and murmured her name; she squeezed his hand briefly.

Captain Brandt sat on a folding stool beside the soldier with the leg wound Harris had cleaned. His shoulders were slumped, his eyes closed, but his hand rested lightly on the patient’s arm, like an anchor.

“Get some rest,” Anna whispered.

“So should you,” he replied without opening his eyes.

She almost laughed.

At first light, the Americans packed up.

Two trucks were designated for the wounded. They were loaded carefully, with German and American medics working side by side, lifting stretchers, securing them with ropes and straps.

Anna and Greta climbed into the back of one of the trucks, settling on the floor near the feet of their patients. Brandt joined them. Becker was loaded into another truck with a different group of wounded.

Before they closed the tailgate, Harris climbed up briefly.

“Here,” he said, handing Anna a small cloth bundle. “Bandage rolls. In case we hit bumps.”

“And coffee,” Greta added, seeing the tin cup tucked into the bundle.

Harris grinned.

“Don’t tell Hardin,” he said. “He’ll say I’m spoiling prisoners.”

Anna looked at the rows of stretchers, then at the American captain.

“Why?” she asked. “Why treat us? Your sergeant said… your brother…”

Harris shrugged.

“I’ve seen enough blood that I’m not impressed by the color of the uniform anymore,” he said. “I’m more interested in whether it stays inside the body.”

He paused, then added:

“And if I was lying on a cot in a tent with a red cross somewhere in your country, I’d hope you’d do the same for me. Might be foolish. Might be idealistic. But that’s the kind of foolish I signed up for.”

The truck jerked as the engine started.

“See you down the road, Anna Keller,” he said, stepping back. “Don’t give the camp nurses too much trouble.”

“I make no promises,” she replied.

He laughed and dropped down as the tailgate clanged shut.

The convoy rolled out, leaving the shredded tents and the blasted crater behind.

As the camp shrank in the distance, Anna felt a strange mix of grief and relief. She was leaving behind the last thing that had felt like hers in this war—the field station, the routine, the illusion of control.

In its place, she had… uncertainty. Wire. A future defined by someone else’s language.

But she also had something she hadn’t expected: the memory of American hands on German wounds, American voices arguing not about how to punish them, but how to keep them alive.

She clung to that as the miles of desert rolled by.

8. Years later

The war ended, as all wars do—not with a neat line drawn in the sand, but with confusion, announcements, and the slow realization that the constant background noise of guns had stopped.

Anna spent the rest of it in a series of POW camps. She worked in infirmaries, translated between German prisoners and American medics, learned better English over shared bandages and late-night conversations.

She saw cruelty, boredom, kindness, pettiness. Camps were not heaven. They were not hell, either. They were holding pens where humanity showed both its worst and better sides in small, daily doses.

She never saw Captain Harris or Lieutenant Monroe again during those years. The war scattered people like seeds in a storm.

After repatriation, Anna returned to a Germany that hardly resembled the one she’d left. Cities she remembered had been reduced to ruins. The government that had sent her to the desert was gone, its leaders defiant or dead, its symbols scraped off buildings.

She kept nursing.

For decades, she worked in hospitals, clinics, and sometimes in makeshift units built after floods or accidents. She married briefly, then widowed early. She didn’t have children, but she had patients—and young nurses she mentored, teaching them the same steadiness she’d learned in tents under foreign skies.

She didn’t talk much about the war. When people asked, she’d shrug.

“I looked after whoever showed up on a stretcher,” she’d say. “That’s all.”

But in her small apartment in a rebuilt city, she kept a box.

Inside were a few photographs, a worn Red Cross armband, a German medal she never wore, and a thin, battered tin cup with English letters scratched faintly along the side:

D. HARRIS

One day, late in life, she received a letter with an unfamiliar stamp.

The return address said: Seattle, Washington, USA.

Her hands trembled as she opened it.

Inside was a neatly written note in clear, slightly wobbly German.

Dear Ms. Keller,

I hope this letter finds you. My name is Laura Harris. I am the granddaughter of Captain Daniel Harris, who served as a doctor with the United States Army in North Africa.

After my grandfather passed away last year, we were going through his things. Among them, we found a notebook of war memories he never published, but wrote for himself. In one chapter, he describes a day when his unit stumbled on a German field hospital in the desert and the argument that followed about what to do.

He wrote about a German nurse named Anna Keller, who stayed behind with the wounded when she could have left. He described how you helped him treat your own soldiers and how, afterward, he always said: “If you want to know why we treat prisoners, ask Anna. She treated us like colleagues even when we had every reason to hate each other.”

He wondered, in the notebook, what had happened to you.

I searched your name, and after some help from archives and veterans’ organizations, I believe I found you.

If this letter reaches the wrong Anna Keller, I apologize. But if you are the nurse my grandfather wrote about, I wanted you to know: he remembered you. All his life. And he taught us, his grandchildren, that mercy is not weakness.

He kept a small German Red Cross armband in his desk as a reminder. I believe it was yours.

If you would like to write back, I would be honored to hear from you.

With respect,

Laura Harris

Anna set the letter down, blinking away sudden tears.

She walked to the box, lifted the lid, and looked at the tin cup with Daniel Harris’s name on it. She remembered the desert, the argument in the tent, the tightness in the sergeant’s jaw, the way Harris’s hands had pressed on a wound without asking what language it groaned in.

She sat at her small table, took out a piece of paper, and began to write.

Dear Ms. Harris,

I am the one your grandfather wrote about. And I remember him too…

As she wrote, the lines between “us” and “them” blurred even further, reduced to something simpler: two medical workers in a hot tent, trying not to let a young man’s heartbeat stop.

She told Laura about the bombing, the argument, the night in the camp. She did not dramatize. She did not romanticize. She just told it straight.

When she was done, she signed her name—Anna Keller, nurse, retired—and laid down her pen.

She thought of all the things she had been taught to believe about Americans before that day in the desert: that they were ruthless, selfish, incapable of mercy.

She thought of the way Sergeant Hardin’s anger had yielded—begrudgingly, but genuinely—to Harris’s insistence that they were not there to kill patients.

She thought of the moment she had realized that propaganda could make monsters out of men who were, in reality, as tired, scared, and complicated as the ones on her own side.

If there was one lesson she took from that day, it was this:

Sometimes the most radical act in a war is not firing a shot.

Sometimes it’s choosing to clean a stranger’s wound, even while your hands shake with the memory of what his uniform represents.

Sometimes, the story you’ve been told about your enemy breaks apart the moment he hands you a cup of terrible coffee and asks, in your language, for more bandages.

Anna sealed the letter.

Outside her window, the world was quiet. No artillery. No engines full of soldiers. Just the hum of traffic and the distant sound of children playing in a courtyard below.

She smiled, faint and tired and true.

The desert felt far away now. But in the heat of that one afternoon, in a torn canvas tent in Africa, a small group of Germans and Americans had chosen something different from what the war expected of them.

They could have written a story of execution.

Instead, they wrote one of treatment, arguments, and bandages.

It wasn’t grand. It didn’t make headlines. It didn’t end the war.

But for the men on those cots—and for one German nurse and one American doctor—it changed everything.

News

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load