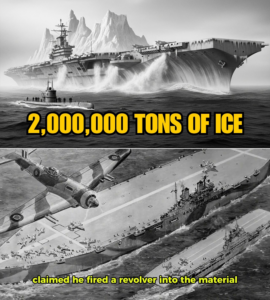

Britain’s Two-Million-Ton Ice Carrier That Wasn’t a Ship but a Strategy—Until Science, Secrecy, and the Atlantic’s Cold Math Said No

The Atlantic didn’t look like a battlefield from a map room in London.

On paper it was a wide, polite blue—some arrows, some dates, some tidy routes drawn with a confident pencil. But in the winter of hard decisions, the Atlantic behaved like a mouth: it opened, it closed, and it swallowed what it pleased.

Commander Elias Markham learned that truth the way most men did in wartime—through missing names.

A convoy report arrived at Combined Operations with its usual clipped phrases: reduced speed… scattered formation… contact lost. The ink dried before the meaning fully sank in. Ships did not vanish dramatically. They simply failed to answer the next signal. The ocean did the rest, quietly, efficiently.

Markham stood in a corridor outside a conference room where the important people spoke. He was a naval architect by training—clean hands, clean math, clean ideas. War had dirtied all three.

Inside the room, a staff officer’s voice carried through the door seam.

“The mid-ocean gap remains the problem,” the man said. “Air cover cannot stay overhead long enough. By the time aircraft arrive, it’s already… over.”

Markham heard the pause, the polite avoidance of details. “Over” could mean many things. It could mean a scattered convoy. It could mean half a convoy. It could mean a captain staring at an empty sea where his friends had been.

A second voice—older, heavier—replied, “Then we build more carriers.”

A third voice answered, irritated. “Steel. Time. Yard capacity. We don’t have all three.”

Markham leaned against the cold wall, listening to the argument he’d heard for months in different rooms with different furniture: we need a floating airfield, and we need it yesterday.

He was about to push away when the door opened and a man stepped out who didn’t look like he belonged in any room, important or otherwise.

He was thin, rumpled, and seemed to have arrived from a different weather system. His coat hung as if it had been negotiated onto his shoulders. His eyes were bright in the way eyes get when sleep has become optional.

The man paused, noticing Markham, and smiled as if they were already friends.

“You,” the man said, pointing lightly. “You’re a builder.”

Markham blinked. “I’m a naval architect.”

“Excellent,” the stranger said. “Then you know the sea is simply a problem of materials.”

Markham almost laughed. “It’s also a problem of the sea.”

“Details,” the stranger replied cheerfully. Then, lowering his voice as if the corridor itself might betray him, he added: “How would you like to build a ship that the ocean cannot sink?”

Markham stared at him.

The stranger extended a hand. “Geoffrey Pyke,” he said, as if that explained everything.

It explained nothing.

Markham hesitated, then shook the offered hand. Pyke’s grip was quick and dry, like a man who shook hands the way he turned pages: urgently.

“A ship that cannot sink?” Markham repeated.

Pyke’s eyes gleamed. “Not cannot. Won’t. Not in any practical sense. It will be too large to lose and too stubborn to break.”

Markham glanced toward the conference room door. Inside, the argument continued, unaware that a stranger had just wandered into the corridor carrying a dangerous sentence.

Pyke leaned closer, conspiratorial. “Tell me, Commander Markham—how much steel does it take to make a carrier?”

“Too much,” Markham said cautiously.

Pyke’s smile widened. “Then don’t use steel.”

Markham’s professional instincts rose like a shield. “A carrier needs strength. Stability. Structure. Armor—”

Pyke lifted a finger. “Ice.”

Markham waited for the punchline that didn’t come.

Pyke continued, unfazed by reason. “Not ordinary ice. Improved ice. A composite. Stronger, slower to melt, obedient under a tool.” He made a small carving motion with his hand, as if whittling a ship out of thin air. “An artificial island that moves where you need it.”

Markham should have dismissed him. He wanted to. He had been trained to respect what could be measured. Yet something in Pyke’s certainty made it difficult to laugh. It wasn’t arrogance. It was… insistence. Like a man who had seen a door in a wall that everyone else believed was solid.

“And what,” Markham said slowly, “would we call this… improved ice?”

Pyke’s gaze darted, as if choosing whether to share a secret with the corridor.

“It will be called pykrete,” he said finally, as if naming it made it real.

Markham opened his mouth—then closed it again.

Pyke clapped his hands once, satisfied. “Wonderful. Come. We’ll make you a believer.”

Before Markham could object, Pyke was already walking, weaving past clerks and officers as if he belonged to the building’s bloodstream.

Markham followed, partly because curiosity is a powerful engine, and partly because the Atlantic kept swallowing names, and any idea that claimed to stop the swallowing deserved, at minimum, one skeptical look.

The demonstration did not happen in a glamorous laboratory.

It happened in a plain room with a plain table and an atmosphere of hurried secrecy. A block of pale material sat in the center, sweating slightly at the edges.

It looked like ice. It did not behave like ice.

Markham watched as a scientist—Max Perutz, introduced with quiet respect—held the block as if it were something both fragile and stubborn. Pyke hovered nearby like an excited conductor.

Perutz explained without theatrics: a mixture of water and wood pulp, frozen into a composite that resisted cracking and melted far more slowly than plain ice. It could be machined, shaped, and—most importantly—survive hard treatment that normal ice could not. Wikipedia

Markham touched the block. It was cold, yes, but not slippery in the way ice usually was. It had a faintly fibrous grip, like frozen paper given bones.

Pyke watched Markham’s expression the way gamblers watch dice.

“Now imagine,” Pyke said, “an enormous hull made of this. Miles of it.”

“Not miles,” Markham said automatically, already calculating. “But it would have to be… very large.”

Pyke beamed. “Exactly.”

A senior officer entered, impatient. Behind him, another—Lord Mountbatten himself, eyes sharp, posture theatrical even in stillness. The room tightened. Men straightened, as if authority changed gravity.

Mountbatten examined the block, then looked at Pyke. “You’re telling me,” he said, “we can build a floating airfield out of this?”

Pyke nodded quickly. “Yes.”

Mountbatten’s gaze flicked to Markham. “And you,” he said, “what do you think?”

Markham chose careful honesty. “If the material holds shape and we can manage melting,” he said, “then it becomes an engineering problem. A very large one.”

Perutz cleared his throat gently. “There is a complication,” he added. “Ice—any ice—flows over time. A ship of this material will sag unless kept sufficiently cold. That requires insulation and refrigeration. Not impossible, but… substantial.” Wikipedia

Mountbatten’s eyes narrowed in interest, not discouragement. “Substantial is acceptable,” he said. “Losing the Atlantic is not.”

Later that week, Markham learned the idea had reached even higher—far higher. A note circulated with the kind of urgency reserved for desperate brilliance, and in it were two words that felt like a spell and a warning:

Project Habakkuk. Wikipedia

The name sounded biblical and absurd, which was probably why it stuck.

And then the project began moving the way truly strange projects move: quietly, quickly, and with a trail of secrecy that made ordinary work feel sinful.

Markham was flown to Canada under an arrangement so discreet it felt like an invention itself.

The official reason on his paperwork was boring. That was the point. If anyone asked, he was assisting with “cold-weather structural testing.” No one asked much, because war created paperwork the way oceans created waves: endlessly and without apology.

He arrived in Jasper National Park under a sky so clean and cold it looked sharpened. Pine trees stood like disciplined guards. The lake—Patricia—sat flat and dark, holding winter like a held breath.

A small camp had been built near its edge: sheds, tarps, cables, and a temporary workshop that smelled of wet sawdust and hot metal from portable heaters. Men moved around quietly, some in uniforms, some not. Markham was told only what he needed, which was both comforting and terrifying.

On the ice of the lake sat the prototype: a rectangular, strange vessel, about sixty feet long and thirty feet wide—an oversized frozen barge with embedded reinforcement and a network of pipes. It looked like a child’s block toy magnified into a secret. It was kept cold by a small motor driving refrigeration. Wikipedia+1

Markham stared at it, trying to feel what his profession demanded: confidence in scale.

But scale was exactly the problem.

The prototype was a whisper of a thing. The planned ship was a shout.

The design sketches Markham saw that first night made his stomach tighten: a proposed floating airfield so enormous it would dwarf any ship in existence, with a flight deck long enough for heavy aircraft and a hull thickness meant to shrug off damage the way cliffs shrugged off waves. Wikipedia+1

In one meeting, a man with tired eyes said, almost casually, “Displacement could be around two million tons.”

Two million tons.

Markham felt his mind rebel. Numbers that large stopped behaving like numbers and became geography.

“That’s not a ship,” he murmured, half to himself.

Perutz, who had flown in briefly, overheard and gave a small, weary smile. “No,” he said. “It’s a decision made physical.”

Night after night, Markham walked the lake’s edge, listening to ice crack softly as temperatures shifted. He watched the prototype’s refrigeration pipes breathe faint fog. He saw men drill into pykrete, saw clean shavings curl away like pale wood. He watched tests that were described with careful understatement: small impacts, stress measurements, durability checks.

Each test answered one question and raised two more.

“How do we keep it cold enough?”

“How do we prevent sag?”

“How do we steer something that large?”

“How do we build it without using more scarce material in the refrigeration plant than a conventional ship would require?” Wikipedia

Markham began to understand that the project’s true enemy was not the Atlantic.

It was physics.

And physics did not negotiate.

Still, there was a fierce kind of hope in the camp. Men wanted the idea to work because the alternative was the ocean continuing to take what it wanted. When the wind howled off the lake at night, Markham imagined it was the Atlantic itself, testing them from across the world.

One evening, Pyke arrived in Canada like a rumor made flesh—coat flapping, eyes bright, speaking too quickly, as if speed could outpace skepticism.

He strode onto the lake, walked up to the prototype, and patted it affectionately.

“There,” he declared. “You see? It’s already a ship.”

Markham stepped beside him. “It’s a frozen platform with a motor,” he said. “And it’s impressive. But the full-scale design is… astonishing. The refrigeration alone—”

Pyke waved a hand. “Details! We do not win by being afraid of pipes.”

Markham exhaled slowly. “We also don’t win by ignoring pipes.”

Pyke turned, studying Markham with sudden seriousness. “Commander,” he said quietly, “you know what the sea has been doing. You know why they brought you here.”

Markham nodded.

Pyke’s voice softened, almost tender. “Then help me build a lie that becomes true.”

Markham looked at the frozen prototype and felt something unexpected: not belief, exactly, but respect for the audacity. It was easy to be sensible in war. Sensible was what everyone did. Audacity was rarer—and sometimes it changed everything.

He nodded once. “I’ll help,” he said.

Pyke’s grin returned like sunrise. “Splendid.”

The months that followed were a strange blend of genius and exhaustion.

Engineers argued about insulation thickness while snow fell like silent applause. Perutz lectured on ice flow and the need to keep the structure around minus sixteen degrees Celsius to limit sagging, which meant ducts and chillers and a cold-blooded heart inside a body made of frozen pulp. Wikipedia

Naval officers argued about steering. Someone suggested differential propulsion. Someone else insisted on a rudder and then realized a rudder for such a vessel would be absurdly large and difficult to control. Wikipedia

Someone else worried about the deck length, takeoff run, and wind patterns. Another man worried about waves and storms and the Atlantic’s habit of turning “reasonable design” into wreckage.

And underneath all of it was the quiet, constant fact: the project existed because the mid-ocean air gap existed—and if that gap closed by other means, the ice ship would become a dream without a purpose.

Markham began receiving updates from the Atlantic in the same clipped language as always, but with subtle changes: longer-range aircraft beginning to push farther, new escort carriers joining convoys, more organized hunter groups, more consistent coverage. Wikipedia

Some nights, alone in the workshop, Markham stared at a penciled cross-section of the proposed hull—so thick it looked like a fortress—and imagined it rolling slowly through the Atlantic like a moving island, aircraft lifting off its back, convoys huddling near it like smaller fish near a whale.

He imagined the ocean trying to swallow it and failing.

He imagined the morale boost of something that absurd: We built an island. What can the sea do now?

Then he imagined the cost sheet.

The cost sheet was always the killjoy. It arrived in envelopes and spoke in numbers that refused romance. The refrigeration plant’s demands grew. The insulation requirements grew. The “simple ice ship” began accumulating metal veins, metal lungs, metal bones, until someone muttered that the “ice carrier” might require more valuable material than a conventional carrier fleet.

Markham began to see the shape of the irony: the ship meant to be built without scarce resources was quietly becoming a different kind of resource monster. Wikipedia

One afternoon, while wind rattled the camp’s thin windows, a senior Canadian administrator visited and spoke with the brittle honesty of a man tasked with saying what others feared.

“It will cost,” the administrator said, “more money and machinery than several conventional carriers.”

Markham didn’t argue. He couldn’t. The numbers had teeth.

That night, Pyke paced like a caged thought.

“They’re afraid,” Pyke said. “They’re letting accountants fight the war.”

Markham kept his voice calm. “They’re letting reality fight.”

Pyke stopped pacing and stared at Markham as if betrayed. “Reality,” he repeated. “Reality is what we change.”

Markham felt a surge of sympathy. Pyke was not wrong. But he was not entirely right either. You could change reality, yes—if you had time. War rarely granted time politely.

Pyke’s shoulders slumped for a moment, the first time Markham had seen him look smaller than his idea.

Then Pyke straightened, stubborn. “We’ll show them,” he said. “One more demonstration. One more proof.”

Markham wanted to tell him proof was not the missing ingredient. The missing ingredient was need. And need was shifting.

But he didn’t say it. He let Pyke keep his fire. It seemed cruel to extinguish it when the Atlantic had already extinguished so much.

The decision came not with a dramatic announcement, but with a meeting that felt like a funeral disguised as a briefing.

Markham flew back to a conference hall where the air smelled of wool and authority. Men in uniform sat in rows. Papers were stacked like small fortresses. The project’s board—Habakkuk’s keepers—spoke in careful tones.

A summary was presented: technical challenges, enormous production requirements, refrigeration complexity, practical steering issues, cost escalation. Wikipedia

Then the final point, delivered quietly, almost mercifully:

Longer-range aircraft and increasing numbers of escort carriers were closing the gap the ice carrier had been meant to solve. Wikipedia

Markham felt something in his chest tighten—not surprise, but a dull ache. He realized he had come to care about the project the way you care about a foolish, brave friend who keeps trying.

Across the room, Pyke sat stiffly, hands clenched, as if holding the idea in place by force. Mountbatten looked unusually still. Even the most powerful men in the room seemed subdued by the simple truth that war moved on, leaving strange inventions behind like footprints in snow.

When the chairman finally said, “The project will be shelved,” the words sounded too gentle for what they meant.

Shelved. Like a book you might return to later.

But Markham knew there would be no later. War was not a library. It was a fire. It took what it needed and burned the rest.

After the meeting, Markham found Pyke alone in a hallway, staring at nothing.

Pyke didn’t look up when Markham approached.

“They’ve decided,” Pyke said flatly.

“Yes,” Markham replied.

Pyke’s voice was thin. “Do you know what they’ll call it, later? They’ll call it a foolish idea. A joke. An eccentricity.”

Markham hesitated. “Maybe. Or maybe they’ll call it what it was.”

Pyke finally looked at him. “And what was it?”

Markham chose his words carefully, because some truths deserved care.

“It was a bridge,” Markham said. “A way to cover a gap when nothing else could. A way to buy time.”

Pyke’s mouth trembled, almost a smile, almost grief. “Time,” he repeated.

Markham nodded. “And in the end, time arrived in other forms.”

Pyke’s gaze drifted away again. “I wanted an island,” he murmured. “A moving island.”

Markham felt an unexpected tenderness. “You got closer than most men ever get to building a myth.”

Pyke let out a short, humorless laugh. “Myths,” he said. “They melt.”

Markham didn’t correct him. He thought of the prototype in Canada, slowly shrinking year by year under summer sun, its metal pieces sinking into the lake like a secret refusing to surface. Wikipedia+1

Before Markham left, Pyke said something that stayed with him longer than any technical diagram.

“Promise me,” Pyke said, voice suddenly sharp, “that you won’t laugh at impossible things.”

Markham met his eyes. “I won’t,” he said. “Not after this.”

Pyke nodded once, satisfied, and walked away down the corridor like a man leaving his own ghost behind.

Years later—long after the Atlantic stopped being a mouth and returned, reluctantly, to being a sea—Markham stood by a quiet Canadian lake with his collar turned up against a mild wind.

The war was over, but not everything it had touched had healed. Markham had become older in ways that had nothing to do with time. He had moved on to other work, other ships, other designs that made sense on paper and behaved sensibly in water.

But he had never forgotten the impossible ship.

The lake was calm. Tourists walked nearby, unaware of the history sleeping under their feet. Somewhere beneath the surface, Markham knew, bits of piping and framing still rested—metal bones of an idea that had once tried to become a strategy.

He stared at the water and imagined the carrier that never was: a colossal pykrete island, longer than any ship, broad as a neighborhood, slow but steady, carrying aircraft and hope into the empty center of the Atlantic. Wikipedia+1

He imagined it not as a weapon, but as a statement: We will not let the sea decide everything.

A child nearby threw a stone. The stone skipped twice and sank, leaving only ripples. The lake swallowed it without drama.

Markham smiled faintly.

Even now, the ocean—and the lakes that pretended to be oceans—kept their habits.

But so did men.

Men still tried to build bridges over fear. Sometimes those bridges were steel. Sometimes they were ideas. Sometimes they were ice reinforced with wood pulp and stubbornness.

Markham turned away from the lake and walked back toward the road, hands in pockets, mind warm with a strange gratitude.

They hadn’t built the two-million-ton ice carrier.

But they had almost built it.

And “almost,” he’d learned, could still change the way you looked at what was possible—especially when the sea was hungry, and the world had run out of easy answers.

News

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat into his first major triumph, the shockwaves reached Rommel himself—forcing a private…

The Day the Numbers Broke the Silence

When Patton’s forces stunned the world by capturing 50,000 enemy troops in a single day, the furious reaction from the…

The Sniper Who Questioned Everything

A skilled German sniper expects only hostility when cornered by Allied soldiers—but instead receives unexpected mercy, sparking a profound journey…

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

The Hour That Shook Two Nations

After watching a mysterious 60-minute demonstration that left him speechless, Churchill traveled to America—where a single unexpected statement he delivered…

End of content

No more pages to load