At a major stateside base, a full-bird colonel openly belittled a reserved female “consultant” as dead weight, unaware she was the combat-tested four-star sent to evaluate his leadership, until one blunt question turned their casual teasing into a career-ending confrontation

I’ve learned that if you want to know what a unit is really like, you don’t walk in wearing four stars and an entourage.

You show up early. Alone. Dressed like you got lost.

People are very honest around someone they think doesn’t matter.

That was the plan the day I walked into Falcon Conference Center on Fort Fremont wearing jeans, desert boots, and a plain black jacket instead of my Class As.

No name tag. No rank. Just a simple badge that said:

REYES, M. – HQ VISITOR

Headquarters had been very clear. The Inspector General’s office had received a cluster of complaints from Falcon Brigade—officially the 18th Combat Readiness Brigade, unofficially “Falcon” because soldiers always rename everything.

Most of the reports fit a pattern:

“Toxic humor.”

“Good old boys club.”

“If you’re not one of them, you’re a problem.”

“Women and quiet guys get rolled.”

None of it was the worst I’d ever seen.

But it had the same smell.

I’ve commanded in combat. I’ve seen what happens when that smell goes unchecked: corners cut, people hurt, missions that should’ve succeeded fall apart because someone all the way up the chain decided the people under them existed to make their ego look good.

Officially, I was there to observe Falcon’s quarterly readiness briefing as the new four-star over Continental Field Operations Command.

Unofficially, I wanted to see if the stories were true—before they saw me as a row of stars instead of as a human being.

So I slipped into the conference center twenty minutes early and took a seat at the back.

Up front, staff scurried around setting up slides. A lieutenant fiddled with a temperamental projector. A sergeant major checked his phone with the weary disgust of a man who’d seen too many PowerPoints.

Nobody looked twice at me.

Perfect.

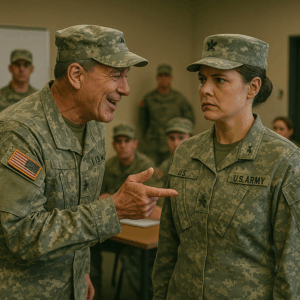

The colonel came in five minutes later.

You could tell he owned the room before he said a word.

Colonel Blake Henderson was tall and broad, with perfect salt-and-pepper hair, a jaw you could use to cut packing tape, and the easy swagger of someone who’d never had to fight for a seat at the table.

His uniform was crisp, chest full of ribbons, airborne and ranger tabs right where the camera would see them. He’d been in for over twenty years and he made sure everyone knew it.

“Heard the big boss is sending someone from HQ today,” he said loudly as he walked to the front. “So if you’re going to lie on your slides, make it convincing.”

Laughter rippled through the front rows.

We’d never met in person, but I knew his file:

Solid combat record in his captain and major years.

Good at talking up results.

Two command climate surveys in the last five years with concerning comments, “addressed internally.”

On paper, he was fine.

Paper doesn’t see everything.

He dropped his folder on the lectern and scanned the room, eyes flicking past me without stopping.

“I see we’ve got half the staff and twice the coffee,” he said. “Typical.”

The lieutenant at the projector chuckled nervously.

“Sir, the visitor from HQ hasn’t checked in yet,” he said. “We’ve got a seat reserved up front.”

“Relax, LT,” Henderson said. “They’ll roll in late, shake a few hands, ask one or two smart questions so they can say they ‘engaged at the tactical level,’ then jet back to the flagpole.”

More laughter.

Upfront, that is.

From my seat at the back, I saw a different reaction—junior officers glancing at each other, a couple of sergeants smirking, one young captain staring fixedly at his notebook.

The colonel clapped his hands once.

“All right,” he said. “Let’s get this circus started. Maybe our mystery guest will grace us with their presence once they’re done fighting traffic on the main post.”

He nodded to the lieutenant.

“Kick it off, LT.”

The lights dimmed.

I listened.

That was my job, before anything else.

I listened to readiness stats, training schedules, maintenance figures, personnel updates.

On the surface, everything sounded pretty good. Falcon Brigade was hitting their numbers. Trained, equipped, “green” across most metrics.

But it was the side comments that told the real story.

“Alpha Company’s behind on their live-fires,” a major said, “but you know, they’ve got a lot of… special soldiers right now.”

Everyone chuckled like they knew what that meant.

“Define ‘special,’ Major,” Henderson said, grinning.

“Uh, sir,” the major said, suddenly cautious. “We’ve got a high concentration of… non-standard recruits. Lateral transfers. New parents. Some folks we’re, uh, growing.”

“You mean women and people who requested religious accommodations,” someone muttered under their breath.

I glanced over. It was the young captain who’d been staring at his notebook. His name tape said DIAZ.

He met my eyes for half a second, then looked away fast.

“Everyone’s special to Brigade,” Henderson said, drawing out the word. “But some folks are… special-er than others.”

A few people laughed again.

I made a note.

The meeting rolled on.

Whenever a subordinate hesitated or stumbled over an answer, Henderson leaned in.

“What’s the problem, Major?” he’d say. “Is the slide too complicated? Did we not use enough pictures?”

When a logistics captain mentioned a delay in receiving new body armor, he shook his head.

“See, this is what happens when we let staff guys who’ve never been outside the wire buy our gear,” he said. “They couldn’t plan a cookout, and they’re in charge of supply chains.”

“Sir,” the captain protested, “to be fair—”

“To be fair,” Henderson cut in, “they’ve never carried 80 pounds of anything that wasn’t a sense of self-importance.”

More laughter.

I watched the room carefully.

Some people laughed because they genuinely thought he was funny.

Some laughed because they felt they had to.

A few didn’t laugh at all.

Those were the ones I was interested in.

About forty minutes into the briefing, after another round of slides about upcoming training, Henderson glanced at the front row and frowned.

“LT,” he said. “Where’s this HQ hotshot? I thought the email said oh-nine hundred.”

“Yes, sir,” the lieutenant said. “Their flight must’ve been delayed or—”

He checked his phone, squinted, then looked up.

“Uh, sir,” he said. “It looks like they signed in at the gate at zero-eight twenty.”

“Then where are they?” Henderson demanded, a little annoyed now. “What, did they get lost between the parking lot and my conference room?”

He swept his gaze across the rows.

Then finally, belatedly, it landed on me.

In the back. Jeans. Plain jacket. Composure.

“Ma’am,” he said, squinting. “You look… new. You with HQ?”

Half the room turned around to look.

I smiled politely.

“Yes, Colonel,” I said. “I’m here from HQ.”

He cocked his head.

“No offense,” he said, “but they didn’t tell me HQ was sending a civilian observer.”

“I was told I was ‘Headquarters representation,’” I said. “The invites from your staff didn’t specify a dress code.”

A few people shifted in their seats.

Henderson chuckled.

“Well, that tracks,” he said. “We’ve got a lot of moving parts here. Sometimes details slip. Next time we’ll make sure to include ‘business casual or better if you want the colonel to take you seriously.’”

Laughter again. Louder this time.

I felt a few eyes on me—not mocking, not amused. Curious. Worried.

I could have stopped it right there.

I could have stood up, introduced myself properly, watched the entire room snap to attention like someone had pulled a fire alarm.

I didn’t.

Not yet.

“Colonel,” I said, still mild, “you said something earlier about wanting to see honesty in the slides. I was hoping that extended to how people talk in the room.”

He shrugged.

“Ma’am, I’m always honest,” he said. “Sometimes a little too honest. Ask anyone.”

He gestured around.

“Right?” he said. “They’ll tell you I don’t sugarcoat.”

There were some nervous chuckles. A sergeant major looked at the floor.

“And the argument became serious…”

You can feel it when a joke crosses an invisible line.

The air gets tighter.

People sit up straighter.

You can almost hear the words leaving someone’s mouth and wonder if they’ll realize what they just said before it’s too late.

“Honesty is good,” I said. “Mocking your own support staff in front of your brigade, though… I’d be careful what you’re teaching your people to laugh at.”

Henderson’s eyebrows went up.

“Ma’am,” he said slowly, “you’re here as an observer, right?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Then observe,” he said. “Let the warfighters handle the warfighter talk.”

A few people winced.

Behind him, Lieutenant Hayes, the brigade’s operations officer, stiffened. He knew—at least vaguely—that someone “important” was coming. He looked like a man watching a train inch toward a broken bridge.

“Sir,” Hayes said quietly. “Maybe we should—”

“It’s fine, LT,” Henderson said, not taking his eyes off me. “If HQ wants to sit in and get some color, they can handle some soldier humor. This is how we talk. You agree, Sergeant Major?”

Sergeant Major Willis hesitated.

“It’s… a high-energy unit, sir,” he said. “We like to keep things lively.”

“That’s one word for it,” I murmured.

“What was that, ma’am?” Henderson asked.

“I said,” I replied, “that I’ve seen ‘lively’ and I’ve seen ‘lazy leadership packaged as charm.’ They’re not the same.”

The quiet captain—Diaz—looked like he wanted to slide under his chair to get away from the blast radius that was building.

Henderson’s smile thinned.

“You got a name, ma’am?” he asked. “Or do we just call you ‘HQ’?”

“Reyes,” I said. “Maya Reyes.”

“Ms. Reyes,” he said, deliberately skipping a title. “Let me explain something from the ground level. You know, where people actually sweat.”

The lieutenant at the projector shifted uncomfortably. A few officers exchanged glances.

“In this brigade,” Henderson said, “we fight. We train. We deploy. We don’t spend our days in cubicles reading policy memos.”

“I’ve noticed policy isn’t your favorite genre,” I said dryly.

He smirked.

“So when some folks at HQ decide to send a civilian out here to make sure we’re using enough buzzwords in our briefings,” he continued, “I’m going to be myself. If that’s a problem, well… that’s why we have chains of command, right?”

He spread his hands, inviting agreement.

Most people stayed very still.

I let the silence stretch.

“Colonel,” I said finally, “I appreciate authenticity. I really do. I also appreciate when leaders model respect, so their people know where the line is.”

“My people know,” he said.

“I’m not so sure,” I replied. “Given what I’ve read.”

His eyes narrowed.

“What you’ve read,” he repeated. “We talking about metrics, or anonymous complaint nonsense?”

“Command climate surveys aren’t nonsense,” I said. “Neither are multiple reports to IG about your so-called ‘traditions.’”

He laughed, abrupt and disbelieving.

“Oh, those,” he said. “You mean the letters we get every time someone’s feelings get hurt because they didn’t get a participation trophy.”

“That’s one way to frame it,” I said. “Another way is: soldiers telling you they don’t feel respected.”

He shook his head.

“With all due respect, Ms. Reyes,” he said, voice edged now, “you’ve been here what, forty minutes? You don’t know this brigade. You don’t know me. You don’t know what it takes to keep a unit like this sharp. So forgive me if I don’t take leadership advice from someone who’s never worn the uniform.”

The room went very, very still.

Behind him, Captain Diaz closed his eyes for half a second.

Up at the side wall, Sergeant Major Willis seemed to stop breathing.

The lieutenant at the front swallowed hard.

Because the thing was—

The colonel wasn’t entirely wrong.

I hadn’t worn the uniform.

I was wearing a jacket and jeans.

I’d worn the uniform that made him possible.

Just not today.

You can let things slide.

Or you can let them land.

I’d come here intending to watch more before showing any cards.

But leadership isn’t about sticking to your script when reality changes.

Reality had just changed.

“Colonel Henderson,” I said calmly, “stand at attention.”

He blinked.

“Excuse me?” he said.

I stood.

“Everyone in this room,” I said, voice steady but carrying, “on your feet. Now.”

Old training kicks in fast.

Chairs scraped. People stood.

Some looked confused; some looked relieved. A few looked almost amused, like they thought this might be some elaborate social experiment.

Henderson stayed by the lectern, boots planted.

“Ma’am,” he said, trying to keep it light. “I don’t know how you run things at HQ, but in this brigade, we—”

His words stalled when the door at the side of the conference room opened.

Brigadier General Patel, the one-star division commander, stepped in.

He was supposed to join us halfway through the briefing, after an earlier meeting across post.

Instead, he’d arrived in time to hear the last five minutes through the cracked door a staff captain hadn’t noticed.

“Colonel Henderson,” Patel said quietly, “you will do as the visitor instructs. Stand at attention.”

Henderson’s mouth opened, then shut.

He obeyed.

His posture snapped rigid. Shoulders square. Hands at his sides.

“Sir,” he said. “I can explain—”

“You’ll have plenty of time to explain,” Patel said. “After you listen.”

He turned to me and gave a small nod.

“General,” he said, clearly and deliberately, “the floor is yours.”

You could feel the shock roll through the room like a tide.

General.

Human brains make funny little noises when they catch up with something in real time.

I watched it hit Henderson.

His eyes flicked from Patel to me. He replayed, in his mind, the last twenty minutes.

His face went a shade paler.

“Ma’am,” he said slowly. “Are you—”

I reached into my jacket pocket and took out my identification.

Nothing fancy. Just a standard government CAC card, slightly more worn than most because I actually used it for more than getting through gates.

I held it up so he could see the line under my photo:

GEN REYES, MAYA A.

COMMANDING GENERAL, US CONTINENTAL FIELD OPERATIONS CMD

His jaw clenched.

“I am,” I said softly, “someone who has worn the uniform long enough to know exactly what it takes to keep a brigade sharp, Colonel. I just didn’t feel the need to walk in here wrapped in my own résumé.”

A few people shifted, eyes wide.

Henderson swallowed hard.

“General Reyes,” he said. “I… apologize if my comments came across—”

“Stop,” I said. “This isn’t about me being offended.”

I looked around the room, meeting as many eyes as I could.

“This is about what you’re telling them is acceptable,” I said. “Day in, day out.”

I turned back to him.

“You said I don’t know your brigade,” I continued. “You’re right that I haven’t commanded this one. But I’ve commanded others. Infantry. Armor. Mixed units. And in every single one, the culture at the top showed up in the smallest interactions.”

I nodded toward the projector.

“You’ve got good numbers,” I said. “On paper. You’re hitting training gates. You’re checking boxes. But what I’ve heard in forty minutes tells me your people are carrying weight that doesn’t show up on slides.”

I gestured toward Diaz.

“Captain, what’s your name?” I asked.

He jumped slightly.

“Diaz, ma’am,” he said. “Captain Julio Diaz. Bravo Battalion S-3.”

“Captain Diaz,” I said. “When Major Ellis made the comment about ‘special’ soldiers, you said something under your breath. What was it?”

A flicker of panic crossed his face.

“I—uh—sorry, ma’am,” he said. “I didn’t mean to—”

“This is a direct question, Captain,” I said. “You’re not in trouble. I want to hear you.”

He swallowed.

“I said, ‘You mean women and people who requested religious accommodations,’ ma’am,” he said.

“Thank you,” I said.

I faced Henderson again.

“You didn’t correct it,” I said. “You made a joke.”

“General,” he said carefully, “we have to be able to blow off steam. These are warfighters. If we police every word, we—”

“You don’t blow off steam on your own people,” I said. “You want to make jokes, make them about yourself. Punching down is lazy.”

I pointed at the logistics captain who’d gotten mocked earlier.

“Captain Lewis,” I said, “how long have you been in the Army?”

“Ten years, ma’am,” she said. “Six as a commissioned officer.”

“You been downrange?” I asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “Twice.”

“Ever carry eighty pounds in anything?” I asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “First deployment. Route clearance platoon.”

I turned back to Henderson.

“So when you implied she’s never carried anything heavier than ‘self-importance,’” I said, “you weren’t just being ‘lively.’ You were lying about her service in front of her peers.”

He opened his mouth and closed it again.

“This might be entertaining for some of you,” I said. “Might even feel like ‘just how we talk.’ But imagine being the person on the receiving end. Once. Twice. For six months. A year. You think you’re getting their best after that? You think they’re giving you bad news early? Or do you think they’re telling you what you want to hear so they don’t become the next punchline?”

Silence.

Even the humming projector sounded loud.

I took a breath.

“Colonel, at the beginning of this briefing, you said you wanted honesty,” I said. “So here’s some.”

I stepped around the end of the row until I was close enough to look him directly in the eyes.

“You’re competent,” I said. “Your brigade isn’t failing its missions. You know how to run a range, how to get through a rotation, how to stand up a task force.”

His shoulders straightened a little, in spite of himself.

“And you are, right now, failing as a leader,” I added. “Because you’ve confused being feared with being respected. You’re entertaining the people who already feel safe and losing the ones who don’t.”

His expression flickered.

“General,” he began. “With all due respect—”

“If you say ‘with all due respect’ and then tell me why I’m wrong about my own experience,” I said, “we’re going to be here all day.”

A few people tried very hard not to smile.

He thought better of whatever he’d been about to say.

I stepped back toward the center of the room.

“This isn’t a court-martial,” I said. “I’m not here to make a dramatic example out of anyone. I am here to make sure the units under my command can do their jobs for the long haul. That means numbers and culture. Both.”

I nodded toward Brigadier General Patel.

“The division commander will handle any formal consequences,” I said. “My concern is bigger than one colonel or one brigade.”

I looked around again.

“So here’s what’s going to happen,” I said.

“First,” I said, “this briefing is over.”

A collective exhale went around the room.

“We’re going to take a ten-minute break,” I continued. “Then Captain Diaz, Captain Lewis, and Major Ellis will meet me and General Patel in the side room. I want to hear from them directly about how this place feels when the slides are off.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Diaz said immediately.

Lewis nodded. Ellis looked like he wanted to evaporate but managed a stiff “Yes, ma’am.”

“Second,” I went on, “Sergeant Major Willis, I want you to start pulling the last three years of command climate survey comments for this brigade. All of them. Not just the summaries. You’ll send them to my office with no names redacted except the submitters’.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Willis said. He sounded… relieved.

“Third,” I said, turning back to Henderson, “Colonel, you and I are going to have a longer conversation with General Patel about how you got here. Not just today, but this command climate. I want you to think about something before we meet.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said tightly.

“I want you to make a list,” I said, “of the last five people who told you ‘no’ and you actually listened. Not HQ. Not higher. People under you. Captains. NCOs. Specialists.”

He blinked.

“If you can’t write down five names,” I said softly, “you’re not leading. You’re performing in front of a mirror. And that isn’t what these soldiers need.”

I let that settle.

Fourth,” I continued, “for the record—there is nothing wrong with soldiers ‘at HQ.’ I’ve lost friends who died in helicopters and in offices. Both were serving. Both matter. We don’t slice each other into ‘real’ and ‘fake’ warfighters. Not in my command.”

Several heads bobbed unconsciously.

I glanced back at my seat, where my notebook sat on the chair, open to a page already half full.

“I’ve been quiet for most of my career,” I said, more conversational now. “I’ve been underestimated. Talked over. Written off as ‘just staff’ more times than I can count. Sometimes it worked in my favor—I got to see people’s real faces before they knew who I was.”

A few people looked down, thinking about the last forty minutes.

“But the thing about underestimating people,” I said, “is it’s contagious. If you as leaders make a game out of mocking the ‘soft’ ones—the quiet ones, the ones doing staff work, the ones who don’t look like the movie poster version of a soldier—your people learn to do the same. And then one day, you find out the person you needed to trust with something critical didn’t trust you enough to bring it to you. Because they learned you’d laugh it off.”

I rested my hand lightly on the back of the chair.

“I cannot afford brigades like that,” I said simply. “The Army cannot afford brigades like that. Not anymore. Not ever, really—but especially not now.”

I straightened.

“You all have ten minutes,” I said. “Get some water. Clear your heads. We’re going to start again, but this time, with the volume turned down on the stand-up routine.”

I looked at Henderson.

“And Colonel,” I added, “next time you assume a woman in jeans hasn’t worn the uniform, consider that the person you’re trying to impress might have written some of the doctrine you’re quoting.”

A couple of the younger soldiers couldn’t help it; they grinned.

“Dismissed for break,” Patel said.

The room broke like surf.

In the side room, with the door closed, people told the truth.

Not all at once. Not in a dramatic flood.

But once someone starts, others follow.

Captain Diaz admitted he’d considered asking for reassignment twice.

“Sir—ma’am,” he corrected himself, flustered, “it’s not that I don’t respect the colonel’s experience. I do. I’ve learned a lot, technically. But you get tired of watching good people get the air taken out of them because they spoke up or didn’t laugh hard enough at a joke.”

Captain Lewis nodded.

“I know I’m good at my job,” she said. “I’ve worked for commanders who made sure I knew it. But here, every supply hiccup turns into a performance where he acts like we’re all incompetent pencil-pushers who’ve never seen dirt. It wears on you.”

Major Ellis looked guilty.

“I shouldn’t have said ‘special,’” he admitted. “I was trying to use the language I thought he wanted. I… I knew it was wrong coming out of my mouth. I just didn’t want to be the next target.”

That, more than anything, told me what I needed to know.

Fear was making cowards out of otherwise decent officers.

That’s what toxic cultures do—they don’t just hurt the obvious targets. They erode everyone’s courage a little at a time.

Brigadier General Patel listened too. To his credit, he didn’t get defensive. He asked questions. Took notes.

“We’re going to fix this,” he said when they were done. “It won’t be overnight. But we will.”

He looked at me.

“Assuming, ma’am, that I keep this command long enough to do it,” he added, only half joking.

“You’re not the problem here, Raj,” I said. “But I am going to hold you accountable for how you respond. That’s the job.”

He nodded.

“I figured,” he said.

As for Colonel Henderson, there were no dramatic fireworks.

No immediate relief of command in front of his troops, no torn-off rank, no shouting.

That’s not how the Army works, most days.

He finished the day’s meetings soberly. No more jokes. No more digs.

He came to my office later that afternoon with his cover in his hands.

“General Reyes,” he said. “I owe you an apology.”

“Yes,” I said. “You do.”

He didn’t try to blame anyone else.

He didn’t pretend he hadn’t known what he was doing.

“I got lazy,” he said. “The humor… it started as a way to keep people awake. Then it became a crutch. Then it became… the whole show.”

“And you forgot it wasn’t about you,” I said.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said quietly.

He took a breath.

“I can do better,” he said. “If you let me.”

I studied him.

A younger version of me might’ve said, Too late. You had your chance.

An older version—the one who’d made mistakes of her own and been allowed to learn from them—knew the value of redemption.

“I’m not here to end your career for sport, Colonel,” I said. “I’m here to make sure the people under you aren’t paying for your blind spots.”

He nodded, eyes tight.

“So here’s what we’re going to do,” I said.

We outlined a plan.

Leadership coaching. A mentor outside his division. A formal letter of reprimand in his file—serious, but not necessarily terminal.

And a probation period, for lack of a better term.

“No more ‘traditions’ that degrade your people,” I said. “No more cheap shots in briefings. You want to lead with humor, fine. Start with yourself. If I hear about one more person leaving this brigade because they felt small, we’ll revisit whether you should be in command at all.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“Also,” I added, “you’re going to stand up in front of your officers and NCOs and own this. Not because HQ made you. Because it’s yours.”

His jaw worked.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said again. “I will.”

“Good,” I said. “Because otherwise, the story they’ll tell about today is ‘the colonel got embarrassed by a four-star.’ That’s not the story I want them to remember.”

He frowned. “What story do you want them to remember, ma’am?”

“That leaders can change,” I said. “And that if you’re going to make fun of people, you’d better be very sure they don’t have four stars in their pocket.”

His mouth twitched despite himself.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

Months later, when I checked back in—not in person, but through the quieter channels leaders actually have to use if they want honest feedback—the story that came back was… different.

Falcon Brigade was still “high-energy.”

They still cracked jokes. No one wants a humorless command.

But the tone had shifted.

Humor became less about punching down and more about shared hardship.

The next command climate survey mentioned the colonel by name in a new way:

“Tough but fair.”

“Actually listened when I told him we had too much on the calendar.”

“Apologized for a comment in front of everyone. That meant something.”

Captain Diaz decided to stay.

Captain Lewis got pushed forward for a key development position instead of being taken for granted in logistics forever.

Major Ellis started catching himself when he softened ugly truths with cute phrases.

And when I visited a year later—this time in uniform, very publicly—Colonel Henderson greeted me at the gate with less swagger and more awareness.

“Welcome back to Falcon, ma’am,” he said.

“Good to be back, Colonel,” I said. “How’s your… warfighter humor these days?”

“Under supervision,” he said dryly. “Mostly mine.”

I smiled.

“That’s all we ask,” I said.

Behind me, a young private whispered to another, “That’s the general who chewed him out last year. Heard he called her a civilian.”

The other private snorted.

“Bet he doesn’t make that mistake again,” he said.

They were right.

But that’s the thing.

The point was never just that a colonel made fun of a woman who outranked him.

The point was that everyone in that room saw what happened next.

They saw that rank, when used right, doesn’t just demand salutes.

It protects.

It corrects.

It says: We can be better than this. And we will.

I don’t need them to remember my name.

I’m fine with being “that quiet lady in jeans” in their stories.

As long as they also remember that on the day their colonel kept making fun of someone he thought was beneath him—

and the argument became serious—

he learned exactly who she was.

And what leadership actually looks like.

THE END

News

My Father Cut Me Out of His Will in Front of the Entire

My Father Cut Me Out of His Will in Front of the Entire Family on Christmas Eve, Handing Everything to…

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After a Local Gang Started Harassing Her, but When Their Leader Mocked…

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,”

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,” then learned her attorney was also her secret…

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog Cornered Him Against the Wall and She Called Him “Dramatic,” but…

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying “Lucky for You I Came Back,” She Thought I’d Be…

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any Humiliating Order to Protect Her Record, Yet the Moment He Tried…

End of content

No more pages to load