“After I gave birth to my daughter, my parents moved into my $5 million house and started running my life—but the very next day I activated a plan I’d prepared in secret, and the fallout stunned absolutely everyone.”

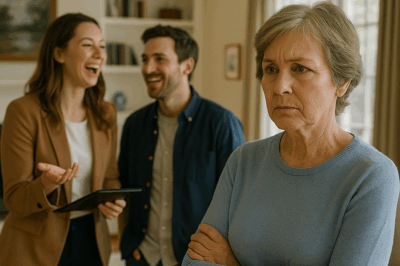

I had imagined coming home with my daughter would feel like stepping into a warm, golden photograph—sunlight on the marble floor, a quiet house, the smell of clean laundry, my husband Zeb whispering, We did it, while we learned the choreography of three a.m. feedings.

What I got, forty-eight hours after a difficult delivery, was the sound of my mother’s voice ricocheting through the foyer like a whistle.

“Shoes off at the door! Where’s the sanitation station? This rug is a germ trapeze.”

I was still in the wheelchair the hospital sent home because my legs felt like foreign language. Zeb pushed me past the stone planters my mother had rearranged overnight. A chalkboard stood propped by the console table with “New Rules” scrawled in perfect handwriting:

No visitors without prior clearance.

Kitchen closed at 8 p.m.

Baby to sleep in our suite until further notice.

Mom rests. (Underlined.)

Grandma in charge of schedule.

“Grandma” was my mother’s preferred title now. She said it like an office. My father stood nearby with the proud, slightly dazed look of a tourist who has mistaken someone else’s home for a museum he funded.

“You’re welcome,” my mother said, sweeping a hand toward the dining room as if she’d staged a reveal. “We moved the bassinet to the east wing for optimal airflow. Zeb, darling, that humidifier is an eye sore; I’ve ordered two that match the fixtures. They’ll be here by noon.”

Zeb’s mouth opened, closed. He looked at me.

“I’ll go put you in the sunroom,” my mother said, already turning, simultaneous with my father trying to roll my suitcase somewhere I did not want it.

“Stop,” I said, and even to my own ears it sounded like a note played on a cracked violin.

They did not.

“Mom,” I tried again. “Please—”

“Sweetheart,” she said, and the word floated like a tissue over a spill. “You hemorrhaged. The nurse told us everything. You need rest. That’s what we’re here for.”

What she meant was: We are the grown-ups. We will fix everything by becoming everything. You are to be grateful and quiet.

My parents are efficient, immaculate, and loud about it. They believe in two truths: that they paid for their own success twice (once in work, once in attitude), and that the second payment gives them lifetime membership to everyone else’s decisions.

It’s not that they don’t love me. They love me like a project. I am a mid-century house that will, in their hands, finally reveal its potential.

By evening, the “bassinet relocation” had grown legs. My mother’s favorite florist arrived with pale hydrangeas the size of volleyballs. A service set out an array of meals in labelled tins as if we were a crew filming a series. My father installed a whiteboard in the kitchen with color-coded feeding times and a note to “confirm Nana’s nights.”

I held my daughter in our bedroom with the door locked until my mother texted, Darling, she needs to acclimate to her grandparent bond. Bring her to the suite for one night. Sleep.

Zeb looked at the ceiling as if answers might bloom there.

“We can say no,” he said.

“Can we?” I asked. “Have we ever successfully said no?”

He half-laughed, half-sighed, then sat on the edge of the bed and laced his fingers with mine on the blanket. “We can now.”

I turned my head so I could breathe the sweet, milky breath of my daughter and felt the first clear thought since we left the hospital: Tomorrow.

I had a plan. It had begun quietly in my third trimester, not out of paranoia but out of a new clarity about lineage and legacy and how I wanted the air to feel in my house. Pregnancy rearranges your furniture and your thresholds. It also rearranges your bravery.

While my mother offered to “handle” the nursery (“just the basics, nothing dusty”), I called my friend Sloane, who is warm-hearted and has a mind like a filing cabinet with roller skates. She is an estate planner and a mother of four who knows both the generosity and the gravity of family.

“I don’t want to cut them out,” I told her, lying on the couch with a belly that felt like its own planet. “I want a boundary with a door.”

Sloane laughed, then got surgical. We created a postpartum plan that sounded clinical but was really a love letter to future me—a version of me who had a baby, and stitches, and a beautiful home that could easily become a stage for someone else’s good intentions.

We didn’t go dramatic. No disinheritances. No feuds codified in legalese. We used the ordinary instruments of adulthood: deeds, notices, calendars, and the kind of calm writing that removes oxygen from arguments.

I:

Placed the house in a revocable living trust with me as trustee and my daughter as beneficiary. That sounds grand, but it simply means the house is owned by a patient folder now, not by my parents’ expectations.

Appointed Sloane as temporary postpartum proxy for household operations for thirty days—a fancy way of saying she could act as property manager if I texted HELP.

Hired a postpartum doula, Nori, to come mornings—a tender force who specializes in asking mothers what they want and believing them.

Wrote a visitation policy with time windows and the kind of gentle firmness you can print and tape to a refrigerator without it looking like a ransom note.

I also replaced our front door lock with an access-controlled smart lock managed by an app that would make a spy jealous. When I first installed it, I felt ridiculous. The ridiculous part ended when my mother left a voicemail explaining where she would keep my keys, just in case I “lost them during baby brain.”

So when my parents claimed the east wing and penciled themselves into the baby’s nights, I slept for three hours, woke into that blue pre-dawn that makes the world look like a bruise, and texted Sloane Now.

She replied with a single check mark.

At nine a.m., a white SUV with the logo of our property management company pulled up. Sloane got out, hair in a low bun, clipboard in that way that signals authority without drama. Behind her was Nori with a bag of muffins that smelled like cinnamon and sanity.

My mother, in a robe like armor, met them in the foyer.

“You can go around back,” she said, assuming they were deliveries.

“Hi, I’m Sloane,” Sloane said, offering the handshake that is both greeting and anchor. “I’m acting as household manager for thirty days, per the trustee. We’re initiating the postpartum plan.”

“The what?” my mother said.

“The plan your daughter prepared,” Sloane said pleasantly. “It includes guest access hours, bedroom boundaries, and a family schedule. I emailed it to both of you last week.”

My father, who has perfected the art of hearing emails only when they align with his impulses, drifted in.

“I’m sorry,” he said, smile tight. “We are the family. We don’t require… management.”

Sloane nodded, an acknowledgment without a concession. “Everyone is family. The plan is for everyone. We’ll go over it together.”

Zeb stood beside me on the stairs with the baby tucked against his chest, her breath painting a warm patch on his shirt. I inhaled the exact courage I had banked for this moment.

“Good morning,” I said, my voice steadier than last night’s violin. “We’re so grateful you’re here. The night was hard. Today we’re going to make it easier. That means we’re going to follow the plan.”

My mother performed a smile. “Of course, sweetheart. But you’re exhausted. You don’t know what you need.”

I kept my eyes kind and unmovable. “I do.”

Sloane set a printed packet on the console with tabs in pastel colors, because presentation matters.

POSTPARTUM HOUSEHOLD PLAN

— Quiet hours: 8 p.m.–8 a.m. (except baby).

— Primary bedroom suite: parents and baby only.

— Baby sleeps in parents’ room unless medically indicated.

— Visitors welcome 10 a.m.–6 p.m., two-hour blocks, with text confirmation morning-of.

— Kitchen open; meals labeled; nursing snacks priority (this made Zeb grin).

— Questions about house operations routed to Sloane.

It looked like a wedding day timeline’s sensible cousin. Underneath, in small type: Household is owned by the Amberlin Family Trust; trustee may appoint temporary manager at her discretion.

“Trust?” my father said, like the word had an aftertaste.

“Yes,” Sloane said. “To simplify things.”

“What things?” my mother said, and there it was: the alarm under the robe.

“Estate things,” Sloane said. “Maintenance, taxes, helper payroll. Nothing dramatic.”

Nori passed a muffin to my mother as if to remind us that breakfast can keep a person from making an enemy of an entire morning. “Blueberry?” she said, smile like a soft light.

My mother declined.

Zeb’s phone buzzed. He glanced at the screen. “The painter’s here to rehang the bassinet art.”

My mother perked, seeing a seam she could slip through. “Perfect. I’ll supervise. The east wing—”

“No,” I said, gently, like placing a wobbly vase on a steady table. “The bassinet is staying with us.”

She turned to my father, then back to me. “You’re making a mistake.”

“I am prepared to make my own,” I said. “That’s motherhood too.”

For a long moment, nothing moved but the second hand on the foyer clock. A neighbor’s car passed, the sound reminding us that the world had not stopped to watch us negotiate.

“Okay,” my father said, surprising me. He sets off fires; he also knows when to put water on them. “Let’s read the plan.”

By afternoon, the house had expelled the weird carnival energy and inhaled something like normal air. My parents took the two-to-four p.m. visitor window; they sat in the living room, my mother knitting something that looked like a tiny hat, my father googling how to fold swaddles as if it were origami.

They were quiet. Nori guided them to quiet. Sloane existed like gravity in a skirt—no scolding, just structure. She collected the chalkboard with “New Rules” and replaced it with a printout titled Welcome, We’re Glad You’re Here and bullet points that said things like Wash your hands, avoid perfume, text before knocking on the bedroom door. Zeb teared up at Bring snacks for the nursing person; she is doing heroic work just breathing while healing.

At five, I fell asleep for a real hour and woke to the sunset making watercolor out of the courtyard.

When I came down to the kitchen, my mother stood at the island staring at the trust document, jaw set in a line that meant she was trying to lift something heavy with pride alone.

“You think we’re the enemy,” she said, not looking at me.

I rested my forearms on the counter. “I think you have always kept us alive by taking charge. I think the way you love can fill a room until it forgets there are other people inside.”

She huffed, which is her way of buying time. “Your grandmother moved in for six months when you were born,” she said. “I would’ve fallen apart.”

“You didn’t have a Zeb,” I said. “Or a Nori. Or… me.”

She looked at me then, truly at me, not the eight-year-old she is perpetually rescuing from cold milk. For a heartbeat, the room flickered between past and present like a slideshow.

“Your house is in a trust,” she said, a different sentence that meant you have a life I don’t know how to walk in.

“It is,” I said. “So it won’t become a tug-of-war.”

“I thought we were helping,” she said.

“You are,” I said. “You will. Within these lines.”

She considered the lines. Then she did a thing I will tell my daughter about when she is twenty and needs proof that people can unlearn.

She nodded.

“Okay,” she said. “Then tell me what to cook for dinner in your kitchen.”

“Chicken soup?” I said, and the word did not feel like surrender. It felt like a bridge.

If the story ended there, it would be small and nice. But the following morning offered the part that turned neighbors’ heads, rang through the group text, and rewired holiday dynamics for good.

At nine, while Nori wore the baby in a sling and taught me the sorcery of a one-hand sandwich, an SUV with a familiar logo rolled up again. A man in a soft blazer got out with a clipboard and a smile undergirded by policy.

“I’m Marco, with Hearth & Haven,” he said, which sounded like a candle shop but was our property manager’s parent company. “We’re here to update guest access.”

My mother straightened, robe traded for a linen shirt that says I host lunches without sweating. “We have access,” she said.

“You do,” Marco said kindly. “Today we’re refreshing it to match the plan. Guest codes will be active ten to six. Bedrooms remain private. Security cameras in common areas will be enabled to protect everyone’s comfort.”

My father bristled. “Cameras? In our daughter’s house?”

“In her trust’s house,” Marco said, not snide, not sharp, simply factual. “Video is only accessible by the trustee or temporary manager. It is not for discipline. It is for clarity, when clarity becomes contested.”

He said it like a weather report. The room absorbed it like a climate.

“Also,” Marco said, flipping a page, “we’ll be moving the east wing luggage to the guest annex. The annex is lovely, has its own patio, and is closer to the side gate.”

My mother looked wounded. “We were… we thought we’d be here. In case she needs us at night.”

“She needs Zeb at night,” Nori said, not unkindly. “Your time is daylight.”

“Come for breakfast,” I said. “Stay for lunch. Take a nap in the annex. We’ll text you pictures of cheeks.”

My mother’s mouth wobbled. Then she laughed, a small sound, like something untying itself.

“Cheeks,” she said. “Fine.”

Marco and a colleague carried suitcases with elegant efficiency. The annex door closed with the soft click of a boundary that is not a barricade.

Ten minutes later, our group chat vibrated with neighbors who had noticed the consolidation of democracy at our house.

HARPER (lot 8): whatever happened over there… I can feel the peace from here.

DAN (lot 12): whoever that woman was—clipboard? queen.

JUNE (lot 3): congrats, mama. say the word if you need a casserole.

I sent a picture of my daughter’s tiny foot with the caption: We’re learning each other.

LINDA (lot 1): (the HOA president who often signs messages “cordially” even when no synonym applies) Welcome home, baby.

I read it twice. It felt ordinary. Which felt miraculous.

The week unfolded like a soft origami back into a paper crane. My mother came in the mornings with fruit cut into geometric optimism. My father learned how to install a car seat and seemed personally offended by its instructions. In the afternoons, they went to the annex to nap and texted me photos of hydrangeas they claimed were bluer than yesterday’s, which is their way of tracking hope.

On Thursday, my mother asked if she could clean the pantry. “I won’t throw anything out,” she said. It sounded like an apology in a new language.

“Okay,” I said. “Thank you.”

She lined the soup cans with a ruler’s ethics. She put the snacks where I could reach them while wearing a baby like a purse. She labeled nothing.

At supper, she ladled chicken soup into bowls and did not tell me to drink it all. She sat on the edge of the sofa and asked about stitches like a woman asking the weather permission to rain.

“You were brave,” she said into the steam.

“I was held,” I said. “By a plan and by people.”

She looked around at the people—Zeb, who smelled like coffee and swaddles; Nori, who could fold a blanket into a cradle; Sloane, who had stopped by to collect a signature and ended up rocking the baby like a lullaby with wrists.

Then my mother did the most surprising thing of all. She turned to Sloane and said, “Teach me the parts of this plan that are for me.”

Sloane nodded. “I’ll bring highlighters.”

My father lifted his spoon. “To highlighters,” he said, and we all laughed, the sound easy.

Months later, when the pediatrician asked how postpartum went, I said, “We activated a plan.” She looked at me as if I had told her the secret to migratory birds. Then she asked for Sloane’s number.

At my daughter’s first birthday, we put a bowl of lemons on the dessert table because they felt like the year: bright, tart, useful. My parents arrived with matching shirts that said “Daylight Crew” because they are both sentimental and committed when you give their love a task.

Neighbors came and brought casseroles and a gnome wearing a party hat because the cul-de-sac enjoys continuity. Someone asked about the moment my parents “took over” and the next day when everything changed.

“Was it the trust?” they asked. “Was it the security cameras? The clipboard? The plan?”

It was those. And it was a sentence I said to myself in the mirror the morning we came home, the weight of my daughter’s small body teaching me beam and ballast at the same time:

You are the mother now.

Not an enemy. Not a supplicant. The steward of the air and the quiet and the daily. The person who can love her parents and hand them the exact hours they can hold and say, This is perfect; this is enough.

If there is a lesson, it is not about five million dollars or marble floors or legal folders. It is about deciding that love can live inside lines and still be love.

The day after my parents tried to make my house their project, I activated a plan that turned them into my team.

The fallout stunned everyone because it wasn’t a fight.

It was a set of doors opening in the right order, until the whole house breathed like a body that finally found its rhythm.

And when my daughter woke that night, as babies do, and Zeb scooped her up and we swayed in the chair with the city’s lights blinking like sleepy stars, I thought of my mother asleep in the annex, of my father rehearsing a lullaby under his breath, of Sloane’s highlighters, of Nori’s muffins, and of the trust that sits in a drawer like a polite guardian.

I whispered to my daughter, “You came home to a house that learned how to be kind,” and in the dark she sighed the sigh of a person who has always known.

News

Her Mother-in-Law Called Her “Lazy” and Refused to Let Her Eat Because She Was Pregnant—But When the Family Doctor Arrived Unexpectedly and Asked One Question, the Truth She’d Been Hiding for Months Finally Shattered the Whole House.

Her Mother-in-Law Called Her “Lazy” and Refused to Let Her Eat Because She Was Pregnant—But When the Family Doctor Arrived…

When My Mom Banned Me From the Family Dinner at a Fancy Restaurant, I Burst Out Laughing and Asked the Owner for a Seat — What Happened Next Made Everyone at the Table Realize Who They Had Truly Been Eating With.

When My Mom Banned Me From the Family Dinner at a Fancy Restaurant, I Burst Out Laughing and Asked the…

“The Lesson They Never Expected to Learn”

After a Group of Students Attacked a Young Teacher, Leaving Her in a Coma, a Single Father and War Veteran…

The Billionaire CEO Pretended to Be Asleep to Test His New Maid’s Honesty — But When He Opened His Eyes and Saw What She Was Doing by His Bedside, He Realized He’d Been Testing the Wrong Person All Along.

The Billionaire CEO Pretended to Be Asleep to Test His New Maid’s Honesty — But When He Opened His Eyes…

My Brother Stole My Film Premiere, My Script, and My Spotlight — He Walked the Red Carpet Wearing My Dream. But Three Days Later, at the Airport, Justice Arrived in an Envelope That Made Him Drop Everything He’d Faked.

My Brother Stole My Film Premiere, My Script, and My Spotlight — He Walked the Red Carpet Wearing My Dream….

I Heard Laughter Coming From My Living Room, But When I Looked Inside, My Daughter-in-Law Was Showing My House to a Buyer—Smiling as If She Already Owned It. What Happened Next Changed Everything I Believed About Family.

I Heard Laughter Coming From My Living Room, But When I Looked Inside, My Daughter-in-Law Was Showing My House to…

End of content

No more pages to load