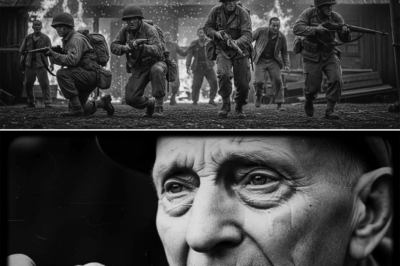

“A Single Metallurgist Broke the War Board’s Rules with a ‘Forbidden’ Alloy for a Mustang’s Heart — Everyone Said He’d Ground the Program, But When the Test Pilot Pushed the Throttle Past Redline, The Needle Crossed 490 and History Learned Who Really Made Fighters Fly.”

On the day they told him not to touch the recipe, Dr. Arthur Keene stared at the memo like it was a bad joke.

WAR PRODUCTION BOARD DIRECTIVE 52-B

No changes to approved alloying schedules. Nickel and molybdenum restricted. Deviations require signatures from three offices and a miracle.

Arthur folded the paper and slid it beneath the blotter of his desk. He could feel the engine throbbing through the hangar floor two buildings away — the Packard-built heart of a Mustang being coaxed to life, coughing, then roaring like a cathedral organ. Somewhere a test crew cheered. Somewhere a pencil snapped.

He reached for the chalk and wrote on the slate behind his chair:

What breaks first?

prop blades? pistons? impeller.

The supercharger impeller — the small, spinning hurricane inside the engine — was the part nobody thought about until it cracked. At altitude, when the thin blue air strangled power, that whirling fan stuffed oxygen back into the cylinders and made the Merlin sing. But push the boost too far, and the impeller’s edges glowed, the steel softened, and small chips turned into ruin.

“Don’t touch the alloy,” the memo said.

“Make it stronger anyway,” the war said.

Arthur slipped his glasses back up his nose and did what metallurgists had always done when cornered: he went to the furnace.

He hadn’t planned to be here — here in Detroit-with-propellers, here in a world where speed was measured in salvation and alloy chemistry could decide who flew home. He’d been the quiet one at university, the kind who carried a microscope the way priests carried prayer books. He studied steels the way poets studied light.

When the war came, all the neat charts were thrown onto the factory floor, and the neat men were told to make miracles. Arthur joined Packard as a specialist because one professor muttered, “They’re going to stuff a British soul into an American chest; your hands are steady.” He learned the Merlin’s temper like a surgeon learns a patient’s heartbeat. If the crankshaft was bone, if pistons were muscle, the impeller was the left ventricle. Overstress it, and the whole body died.

He ran test cycles until dawn blurred the gauges. He ruined batch after batch in the name of better. He asked for more nickel and was laughed at. He asked for cobalt and was told to pick a different continent. So he reached for elements that hid in footnotes: vanadium and molybdenum in whispers, a dusting of titanium in the grain boundaries, boron in a trace so small it was more rumor than ingredient.

“Forbidden,” said the procurement officer, tapping the memo. “Moly’s for armor. Besides, you’re playing with our permit.”

Arthur plucked the memo from beneath the man’s finger and slid a cup of coffee across the desk instead.

“Armor keeps men alive on the ground,” he said softly. “This will keep them alive in the sky.”

The officer stared at him for a long moment, then looked away. “If this goes wrong, you and your trace boron will both vanish into paperwork.”

Arthur nodded. “If it goes right, no one will know my name.”

Outside, on the tarmac washed in cold morning light, Test Pilot Evelyn Shaw zipped her jacket and squinted toward the hangar where Arthur’s furnace always glowed like a second sunrise. She’d flown everything from trainers to temperamental hot rods, but the Mustang felt like it was humming in her bones. On paper, her squadron had been told to expect 430, maybe 440 miles per hour level, depending on altitude and optimism. In whispered hangar talk, they joked about 460 in a shallow dive. Nobody sane said 490.

Evelyn wasn’t always sane when it came to speed.

“New impellers went into V-1650-7C yesterday,” said Chief Mechanic Harlan, handing her a clipboard. “Keene’s secret sauce. You didn’t hear that from me.”

Evelyn cocked an eyebrow. “Are they going to sing or explode?”

Harlan grinned. “Doc says they’ll sing loud. Says you’ll run out of courage before they run out of strength.”

She signed the sheet, glanced across the hangar window, and saw Arthur for the first time — a thin man with furnace-burned sleeves and chalk on his hands, standing like a courtroom defendant waiting for a verdict. He tipped an invisible hat. She returned it.

The first trial began just after dawn. The air over Willow Run was thin and white, still honest enough to tell a pilot the truth. Evelyn rolled to the end of the runway, stood on the brakes, and eased the throttle forward. The Merlin coughed once, then turned feral, the prop slicing the morning into ribbons.

“Control, Mustang Three on climb,” she said, voice steady. “Taking her to twenty-five.”

Under her boots, the deck vibrated like a living thing. Behind her lungs, the supercharger spun past reason, and the sound turned from roar to whistle — that beautiful, rising keening that told her the impeller had found its note.

At eighteen thousand feet, the air thinned. At twenty-two, the world began that delicious blur where sky goes from blue to black and the earth acquires the geometry of maps.

“Boost, 64 inches… 70… stable,” she reported. “Temperatures… good.”

Below, in the lab, Arthur’s pencil chewed a groove through paper. He watched the telemetry needles trace their quiet lines and waited for the impeller signature — that small, characteristic vibration at certain harmonics. It came, flirted with limits, then settled like a cat in a windowsill. He exhaled.

“Copy, Mustang Three,” Control answered. “You’re clear for the run.”

Evelyn leveled off, felt the small shiver of laminar flow settling like silk over the wing, and nudged the throttle past the painted red arc where manuals said, with exquisite politeness, please don’t.

The sound shifted. The whistle deepened. The airplane turned from machine to idea.

“Indicating… four-six-zero,” she said, breath catching. “Four-seven-five… four-eight-five…”

The needle quivered, the cockpit trembled the way a held breath does. She felt the old superstitions crawl up her spine — not fear, exactly, but the knowledge that a thousand tiny things had to go right for a number to stay obedient.

“Four… nine… zero,” she whispered.

Somewhere below, a fist hit a table. Somewhere above, a hawk folded its wings and let gravity take it. Evelyn smiled — a thin, private thing — and eased the throttle back with a grace normally reserved for holding hands.

“Stabilizing. Returning with all parts in original positions,” she said, and laughed despite herself.

Down on the hangar floor, Harlan clapped Arthur so hard on the back he nearly knocked him into the furnace. “You sly fox,” the mechanic shouted. “You conjured strength out of thin air!”

Arthur rubbed at his eyes with sooty fingers and only said, “Not thin air. Thin grain boundaries.”

Praise was a cheap metal in war; it arrived bright, tarnished quickly, and was often stored in drawers. Within days, the directive memo turned into a meeting, and the meeting turned into a tribunal of sorts. Three men in tidy suits, armed with clipboards and the power to cancel.

“You broke Directive 52-B,” said the first.

Arthur folded his hands. “I adjusted the boundary composition of a high-speed steel in service of survivability at altitude.”

“You added restricted elements,” said the second. “Molybdenum allocation—”

“I asked for scraps from a rejected armor batch,” Arthur said. “I needed ounces, not tons.”

The third leaned forward. “And did you consider the risk if your impeller exploded at thirty thousand feet and tore the engine apart?”

Arthur considered the ceiling. “Every night,” he said softly. “I did the math until my eyes burned and made the grain smaller until the metal forgot how to fail.”

“Metals don’t forget,” the first said.

Arthur’s mouth tilted. “Sometimes they do if you teach them how.”

The room was quiet a long time. Finally the second man spoke, not unkindly. “We run a war with rules, Doctor. Not because rules are holy, but because chaos is hungry.”

Arthur nodded. “And sometimes you starve chaos by feeding it a better alloy.”

They cleared him with a reprimand — the bureaucratic version of a scar. It would live in a file. It would ache in bad weather. It would remind him what it cost to bend a rule without breaking a man.

News traveled along runways and barroom counters faster than it traveled through newspapers. Pilots noticed what numbers did; crew chiefs noticed what knuckles felt on the cowling after a landing. The squadron got the “Keene wheels,” as someone misnamed them, and soon the misnomer stuck — impeller, wheel, halo, whatever. The thing spun. The boost held. The engines sang at altitudes where the cold made men think of home and numbers mattered more than swagger.

Evelyn shipped out.

She wrote Arthur once, on thin paper that carried the smell of fuel and weather:

Doc,

Today the sky was a chessboard. I played a queen with the engine you taught to bite. We were supposed to be an escort, eyes out, hands steady. But the call came over the set — bandits above, fast. We didn’t go hunting. We went home-protecting. But home was moving at 280 knots and needed another minute of breathing room.

I gave her three.

I did something you won’t like — I pulled the throttle where your notes have that little skull-and-crossbones doodle. We leveled, then we ran. He tried to follow. He couldn’t. My gauges kept their secrets. Your wheel kept its promise. We brought everyone back.

P.S. You don’t know me, but you do.

— E.

Arthur folded the letter and put it with the reprimand. He decided life was neat when its papers were arranged in contradiction.

Years blurred into finishes and refits and the kind of exhaustion that looks like competence from a distance. The war — that large, loud machine made of small, quiet decisions — swung the way machines do when the bearings are oiled and the belts don’t slip. Men came home, some with their own reprimands, some with their own scars. Weapons were mothballed. Factories learned to make refrigerators. The furnace learned to sleep.

The file on Arthur’s alloy — stamped TEMPORARY APPROVAL in a hurry and then CLASSIFIED by habit — vanished into a drawer nobody opened. Evelyn’s logbook, full of small notes in a small hand, went to a shelf that gathered dust across three moves and one marriage. The engineers who knew how to taste a steel with their fingertips aged into the sort of polite men who mowed their lawns on Saturdays and still flinched when thunder sounded like turbines.

Decades later, a museum curator with a stubborn streak opened a box labeled PACKARD: MISC. He sifted past invoices and memos until he found two pieces of paper clipped together — a reprimand and a letter that smelled faintly like rain.

He telephoned a woman in her late nineties whose name he’d found in a footnote. “Ms. Shaw,” he said, “we’re building a display about the quiet hands behind the loud airplanes. There’s a name here — Arthur Keene — and a story about an impeller.”

On the other end of the line, Evelyn laughed and coughed in the same breath. “If your display has a furnace and a chalkboard, you’re halfway there.”

“And if it has a speed placard that says 490?”

“Make it small,” she said. “Numbers are shy in old age.”

“Did you really—?”

“Yes,” she said, voice a little softer. “He gave me the edge that gave boys time to live. Put that on the wall if you need something to carve.”

“What should we call the alloy?”

There was a long pause. “He called it nothing,” she said finally. “Because real miracles don’t need names to work.”

On the day of the dedication, schoolchildren pressed their hands to the glass where an impeller, polished to a shy shine, sat like a crown. A plaque told a story short enough to fit between two breaths:

In a war of rules and shortages, a metallurgist changed nothing on paper and everything in practice. He moved atoms, not headlines. Pilots outran danger because grains refused to grow under heat. This wheel isn’t big. Neither is courage at its beginning.

An elderly man in a good suit stepped close and leaned in until his breath fogged the case. He could smell a phantom of oil and hot varnish, the ghosts that live forever in steel. He thought about memos and meetings and the way you sometimes ask forgiveness instead of permission when men’s lives measure the difference. He thought about the way a chalk squeak can sound like a symphony when you finally solve a stubborn equation.

“Thank you,” he whispered to no one in particular.

Two exhibits over, children listened to a docent describe laminar flow, and one girl raised her hand to ask, “Did they really go that fast?” The docent, who had learned to love truth the way one learns to love bread, said, “Sometimes faster than they admitted.”

Outside, a blue sky did what blue skies do — pretended to be simple while hiding a thousand pressures and a million particles all negotiating how to be together. In an old house on a quiet street, Evelyn napped in a chair near an open window. The breeze smelled like cut grass and gasoline, which meant summer. She dreamed, briefly, of altimeters and of a soft whistle that only a few ever hear: the sound of a forbidden alloy refusing to quit when the air itself said please.

And somewhere in a thin file that had crossed oceans of bureaucracy to lie on a museum lawyer’s desk, a reprimand grew nobler with age — proof that sometimes you draw a sharp line through a rule and call it a signature.

News

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose From the Dust to Prove Skill, Honor, and Command Presence Matter More Than Intimidation or Muscle

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose…

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders, and Quietly Shifted the Balance of a War Few Understood Was Already Changing

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders,…

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a Force Far Stronger and Sparked One of the Most Astonishing Moments of Bravery in Naval History

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a…

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable Trial That Exposed the Fragility of Power and the Hidden Strength of Ordinary People During the Hamburg Crisis

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable…

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into the Pivotal Moment Changing an Entire War at the Battle of Midway

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into…

Five Hundred Eleven Men Faced an Unthinkable Fate in the Final Minutes, Until a Group of Rangers Arrived and Sparked a Fierce Debate About Duty, Courage, and the True Meaning of Rescue Under Impossible Pressure

Five Hundred Eleven Men Faced an Unthinkable Fate in the Final Minutes, Until a Group of Rangers Arrived and Sparked…

End of content

No more pages to load