What the German High Command Whispered in Shock and Confusion as Patton Turned His Entire Army Ninety Degrees During a Relentless Winter Blizzard That Ignited the Most Tense and Heated Strategic Debate of the Ardennes Campaign

The snowstorm rolled across the Ardennes like a white curtain being drawn over a stage, blotting out the forests, the winding roads, and the dim glow of distant towns. Wind howled through frozen branches and piled drifts against stone farmhouses. It was the kind of winter storm that seemed to muffle the world—except for the booming artillery that echoed far in the distance.

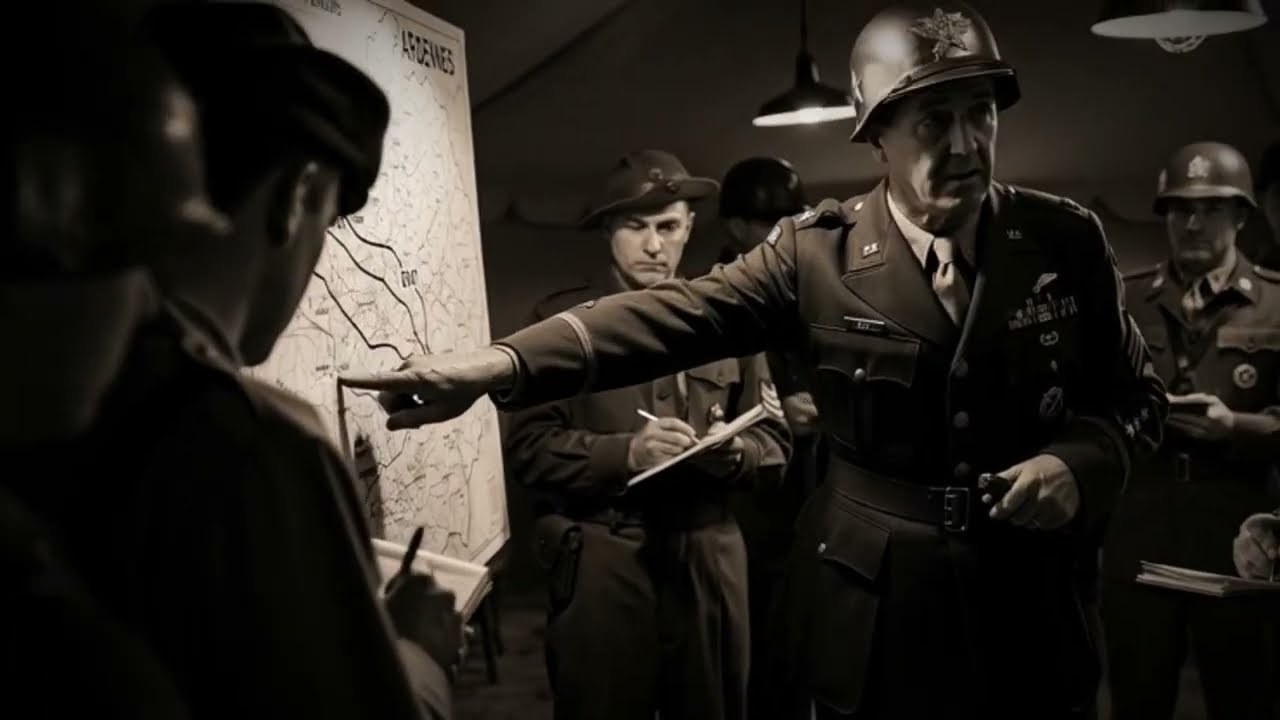

Inside the German High Command’s forward headquarters, once a quiet Belgian manor house, tension simmered beneath the sarcastic calm of officers hunched over maps. Candles flickered. Boots thumped. Radios crackled. On the walls, shadows swayed like restless spirits as the storm battered the windows.

The offensive that German leaders hoped would turn the tide—their bold winter push through the Ardennes—had begun with surprising momentum. For a moment, it seemed to them that the wind of fortune had shifted. Some divisions achieved breakthroughs, others forced Allied units into confusion, and many believed the plan still carried the potential to fracture the enemy front.

But by the third week of December 1944, whispers of trouble had begun.

And now, something even more unsettling had arrived.

A captain rushed into the map room, snow clinging to his coat, breath visible in the freezing air.

“Report from the southern sector!” he announced, handing over a folder.

The senior officers exchanged tired glances. They were used to constant updates, but something in the young captain’s eyes set them on edge.

Generaloberst Hans Krüger, one of the key planners of the operation, opened the folder and scanned the preliminary message. His eyebrow twitched.

“What is it?” another officer asked.

Krüger read the line again, slower this time.

“It appears,” he said, “that the Americans… are turning.”

“Turning how?” someone asked.

“Turning where?” another added.

Krüger exhaled sharply, fog rising from his breath.

“Turning their entire army,” he said. “Ninety degrees. In this blizzard.”

The room fell silent.

Even the wind outside seemed to pause, as if waiting for an explanation that didn’t come.

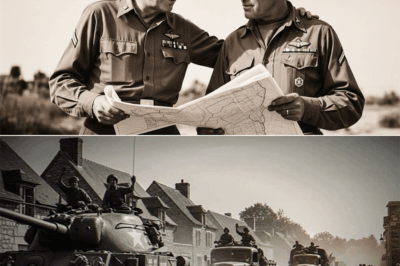

Across the Ardennes, the Third Army of the United States was already deep in motion. Trucks coughed through snow. Columns of tanks crawled along icy roads. Artillery rumbled north. The terrain was unforgiving, the cold brutal. But the soldiers moved with a sense of purpose that defied the storm.

General George S. Patton Jr. had visited the front hours earlier, encouraging his men with quick, sharp remarks and a determination that felt almost contagious. When he spoke of reaching the surrounded American forces in Bastogne, his confidence was not grandstanding—it was a promise.

“We move now,” he told them. “Not tomorrow. Not when it’s easier. Now.”

And they moved.

Back in the German command room, Krüger studied the map with a frown. Snowflakes tapped against the windows like insistent fingers.

“Ninety degrees…” he muttered. “He’s swinging his army north.”

“But the weather—” one general began.

“—should make that impossible,” another finished.

The officers stared at one another as the implications sank in. Their entire southern flank was built on the assumption that the Americans would remain reactive and disorganized.

And now one of their most aggressive commanders was refusing to stay still.

Krüger turned to his intelligence officer. “How fast are they moving?”

“We… don’t know yet. Reports are incomplete. Visibility is nearly zero.”

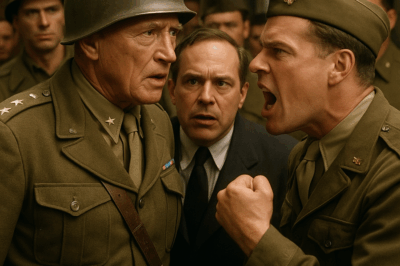

The room erupted into debate.

“He can’t move armor through that terrain!”

“The roads are frozen. They’ll advance slowly.”

“But if he tries it, our timetable collapses.”

“It’s a bluff. It must be.”

“No,” Krüger said, raising a hand. “Patton does not bluff.”

That statement brought a hush to the room.

For all their contempt for Allied leadership, even the German High Command had learned to treat Patton’s unpredictability with caution. His rapid maneuvers in earlier campaigns had been studied, analyzed, and grudgingly respected.

But turning an entire army in a blizzard? That seemed like madness.

Or brilliance.

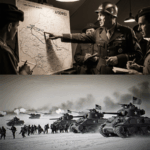

Snow continued to fall thickly, coating tanks and trucks as the Third Army pushed forward. Soldiers huddled under blankets when they could, but most simply tightened their gear and pressed on.

Small towns flickered past—villages that looked half-asleep beneath layers of white. The roads twisted through forests where trees sagged under ice, their branches drooping like weary soldiers.

Along the way, Patton stopped at command posts to check progress. He seemed energized by the challenge, moving briskly from unit to unit, scribbling adjustments on maps, barking encouragement at officers.

“We have friends waiting for us,” he said. “Let’s not keep them waiting.”

Inside German headquarters, the argument escalated.

“If Patton reaches Bastogne, we lose the crossroads.”

“If he breaks the encirclement, our momentum dies.”

“His movement creates vulnerabilities. If we strike fast enough—”

“With what?” another officer snapped. “The enemy is shifting, yes, but our own forces are stretched thin.”

Krüger rubbed his temples, frustration tightening his jaw.

“This storm was supposed to ground their aircraft,” one staffer insisted.

“And it has,” Krüger admitted. “But it hasn’t frozen their will.”

A lieutenant entered with a fresh report. The tension in his posture was unmistakable.

“More sightings of armored columns heading north,” he said. “Multiple units. It’s confirmed, sir.”

The room reacted like an electrical current had run through it.

“This is unacceptable!”

“He’s throwing out the rulebook!”

“This isn’t the sort of maneuver any rational commander attempts in winter.”

Krüger’s voice cut through the noise:

“He’s betting everything.”

And then, almost to himself:

“And he believes he can win.”

Far to the north, inside Bastogne, the men of the 101st Airborne Division held firm despite dwindling supplies. The storm worked both for them and against them—concealing their positions, but also limiting what little aid could reach them.

Still, they refused to give up.

They dug deeper. They rationed their ammunition. They made repairs to weapons with numb hands. They shared whatever warmth they could find.

And they waited.

Meanwhile, the German High Command’s frustration grew.

“If he succeeds,” one general said, “our entire offensive loses its backbone.”

“And if he fails,” another countered, “he will have overextended himself.”

Krüger pointed at the map.

“Patton is not moving one division. He is not moving one corps. He is moving an army. In weather that should prevent any coordinated advance.”

Another officer added, “He must have prepared for this.”

Krüger nodded reluctantly.

“Yes. He must have prepared days ago.”

Silence followed.

Because that meant something even more unsettling:

Patton had anticipated the crisis.

And he had been ready.

At the same time, the Third Army’s advance continued. Soldiers helped push vehicles stuck in snow. Engineers cleared paths. Tank crews scraped ice from treads. Even in the worst moments—when trucks stalled, or when exhausted men stumbled through the darkness—the momentum never stopped.

Patton himself seemed immune to doubt.

“We’re close,” he told his staff. “Closer than they believe.”

German commanders, unable to reconcile what was happening with what they expected to happen, continued their debates long into the night.

“Should we reinforce the southern flank?”

“We don’t have enough reserves.”

“What if he reaches Bastogne tomorrow?”

“It would mean the encirclement collapses.”

“We must respond!”

But Krüger, exhausted yet sharply aware, whispered something that made even the staunchest officers pause:

“Perhaps… we underestimated his resolve.”

Another general sighed, rubbing frost from his gloves.

“Resolve alone doesn’t move divisions through a blizzard.”

“No,” Krüger said. “But resolve is what makes soldiers obey the order to try.”

For the first time since the offensive began, unease filled the room.

And then came the message they had dreaded.

A radio operator, pale and shaken, handed Krüger a sheet.

He read it once. His lips tightened.

“What does it say?” someone asked.

Krüger exhaled slowly.

“He’s reached them,” he said.

The room froze.

“Patton has linked up with the forces in Bastogne.”

A stunned silence spread like frost over glass.

“This cannot be…”

“In this weather…”

“With those roads…”

Krüger folded the message carefully.

“He turned his army ninety degrees,” he said. “And he did it faster than we believed possible.”

The storm outside seemed to grow louder, as if echoing the turmoil within the room.

One general whispered, almost reluctantly:

“He has reshaped the battle.”

Meanwhile, in Bastogne, American soldiers cheered as columns of tanks and infantry broke through the snow. Relief washed over men who had endured sleepless nights and relentless cold.

Some cried quietly. Others laughed. Many simply slumped in the snow, too exhausted even to celebrate properly.

But hope had arrived. And it had come in the form of a maneuver so audacious that even their commanders had not expected it to succeed so quickly.

Patton arrived later to inspect the situation, his boots crunching in the snow. Officers saluted as he passed. Paratroopers stared with disbelief and relief, whispering to one another.

He stopped near a group of soldiers who had just been resupplied.

“General,” one of them said, “we thought no one could break through.”

Patton gave a small, tired smile.

“Sometimes,” he replied, “you do things simply because people say they can’t be done.”

Back in the German High Command, the mood had shifted from tension to grim acceptance.

Krüger summarized it best.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “we have witnessed something rare today.”

“What’s that?” someone asked bitterly.

“A commander who does not obey the limits of the weather, or the terrain, or our predictions.”

He looked around the room.

“And now we must adjust our plans accordingly.”

No one argued. They all understood the truth.

Patton had changed the battlefield in a single, sweeping maneuver.

A ninety-degree turn in a blizzard—an act that defied logic, weather, and expectations.

And it had worked.

Historians would later analyze the operation endlessly—its timing, logistics, daring, and consequences. They would dig into the decisions of both sides and debate endless “what ifs.”

But the German commanders who lived through that moment needed no academic explanation.

They had seen the impossible happen in real time.

And their whispered shock, spoken in the cold map room as snow hammered the windows, would remain an unrecorded but unforgettable truth:

“Patton turned his army in a blizzard. And we never saw it coming.”

News

What German Children Saw Falling From the Sky That Morning—and How the Unexpected Discovery Sparked the Most Intense Strategic Argument Among Allied and Axis Commanders During a Critical Turning Point in the European Campaign

What German Children Saw Falling From the Sky That Morning—and How the Unexpected Discovery Sparked the Most Intense Strategic Argument…

The Eighteen Startling Realities Patton Witnessed in Sicily That Forced the Allies into Their Most Heated Strategic Debate and Forever Changed Their Understanding of the Campaign’s Hidden Dangers and Unexpected Opportunities

The Eighteen Startling Realities Patton Witnessed in Sicily That Forced the Allies into Their Most Heated Strategic Debate and Forever…

The Twenty Bold Armored Maneuvers Patton Unleashed to Break the German War Machine When Strategic Tensions Reached Their Fiercest Point and Allied Command Debated Whether His Rapid Tank Warfare Would Save or Endanger the Entire Campaign

The Twenty Bold Armored Maneuvers Patton Unleashed to Break the German War Machine When Strategic Tensions Reached Their Fiercest Point…

The Fifteen Bold, Unpredictable, and Controversially Brilliant Decisions Montgomery Never Expected George S. Patton to Risk During the Most Tense Strategic Arguments of the European Campaign, When Every Move Threatened to Reshape the Allied Command’s Fragile Balance

The Fifteen Bold, Unpredictable, and Controversially Brilliant Decisions Montgomery Never Expected George S. Patton to Risk During the Most Tense…

When Leadership, Instinct, and Defiance Collided: The Day Patton Broke the One Sacred Order He Was Never Supposed to Violate—And the Remark from Eisenhower That Changed Their Tense Confrontation Forever

When Leadership, Instinct, and Defiance Collided: The Day Patton Broke the One Sacred Order He Was Never Supposed to Violate—And…

How George S. Patton’s Unpredictable Moves Shattered Every German Expectation: The Fifteen Bold Decisions That Reshaped a Theater of War and Sparked Endless Debate Among Allied Commanders

How George S. Patton’s Unpredictable Moves Shattered Every German Expectation: The Fifteen Bold Decisions That Reshaped a Theater of War…

End of content

No more pages to load