-

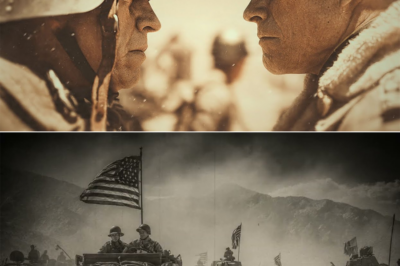

Why Hardened German POW Doctors Broke Down Sobbing the First Time They Stepped Inside an American WWII Field Hospital and Realized What Their Own Soldiers Had Been Denied

Why Hardened German POW Doctors Broke Down Sobbing the First Time They Stepped Inside an American WWII Field Hospital and…

-

How a Wounded Enemy General Awoke on an American Operating Table, Discovered Unthinkable Mercy, and Sparked a Quiet Rebellion that Outlived the War Itself

How a Wounded Enemy General Awoke on an American Operating Table, Discovered Unthinkable Mercy, and Sparked a Quiet Rebellion that…

-

What the German High Command Finally Admitted in Panic-Filled Bunkers When They Realized D-Day Was the Real Invasion and Not Another Clever Allied Deception

What the German High Command Finally Admitted in Panic-Filled Bunkers When They Realized D-Day Was the Real Invasion and Not…

-

What Stalin Finally Whispered in the Kremlin War Room When America’s First Arctic Convoy Emerged from the Mist and Changed the Fate of His Bleeding Eastern Front

What Stalin Finally Whispered in the Kremlin War Room When America’s First Arctic Convoy Emerged from the Mist and Changed…

-

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

-

The Jeep That Shouldn’t Have Existed

German forces were stunned when a bizarre, heavily modified Allied jeep roared onto the battlefield—its speed, deception, and precision disabling…

-

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

-

The Tank That Had No Name

When a mysterious Allied “ghost tank” appeared on the battlefield, German crews couldn’t identify it—until the unknown machine outmaneuvered their…

-

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

-

The Summer France Found Its Thunder

As Patton’s armored columns swept across France with breathtaking speed, Bradley’s stunned reaction behind closed doors revealed admiration, disbelief, and…

-

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

-

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

-

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany, the stunned reaction inside German High…

-

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat into his first major triumph, the shockwaves reached Rommel himself—forcing a private…

-

The Day the Numbers Broke the Silence

When Patton’s forces stunned the world by capturing 50,000 enemy troops in a single day, the furious reaction from the…

-

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

-

The Sniper Who Questioned Everything

A skilled German sniper expects only hostility when cornered by Allied soldiers—but instead receives unexpected mercy, sparking a profound journey…

-

“He Divorced Me Without Warning, Threw Me Out of the House I Helped Build, and Watched Me Walk Away With Nothing—But Months Later, He and His Entire Family Appeared at My Gate in Tears After Discovering a Secret That Turned Their World Upside Down Forever”

“He Divorced Me Without Warning, Threw Me Out of the House I Helped Build, and Watched Me Walk Away With…

-

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

-

“I Transformed My Father-in-Law From a Struggling Business Owner Into a Millionaire, Only for Him to Cast Me Aside and Replace Me with His Son—But What I Discovered After Their Betrayal Led to a Stunning Turn of Events Neither of Them Ever Expected”

“I Transformed My Father-in-Law From a Struggling Business Owner Into a Millionaire, Only for Him to Cast Me Aside and…