What Churchill Quietly Remarked When Patton’s Relentless Advance Helped Seal the Falaise Pocket, Trapping an Entire German Army and Changing the Shape of Victory in Western Europe

In August 1944, as the Allied armies surged across Normandy, Winston Churchill sat far from the dust and thunder of the battlefield, yet closer to its consequences than most men would ever be. He stood before a large wall map, cigar in hand, eyes narrowed, watching a shape begin to form—slowly at first, then with terrifying clarity.

It was not a line.

It was a closing fist.

Reports arrived from France in rapid succession. British, Canadian, and American forces were tightening their grip. To the north, Allied units pressed downward. To the south, an American army under George S. Patton was moving with an urgency that seemed almost reckless.

Between them, an enormous German force was being squeezed into a shrinking space near a small French town few had heard of before the war.

Falaise.

Churchill had seen many battles unfold on maps before. He had lived through defeats, delays, and disasters that tested the limits of his resolve. But as he watched the developing encirclement, he sensed something different.

This was not merely a victory taking shape.

This was an ending.

A Prime Minister Watches the Trap Close

Churchill’s war room was quiet that morning, unusually so. Advisors stood nearby, careful not to interrupt his concentration. The Prime Minister leaned forward, tracing the movement of Allied units with a finger, pausing often over the arrows representing Patton’s Third Army.

“They are moving very fast,” Churchill said at last.

A senior officer nodded. “Faster than anticipated, Prime Minister. Patton is pushing hard from the south.”

Churchill grunted thoughtfully. He had always held mixed feelings about Patton. Admiration tangled with unease. He admired boldness—perhaps more than most—but he also understood how easily boldness could slip into chaos.

And yet, there it was.

Patton’s advance was not chaotic. It was deliberate, relentless, and frighteningly effective.

As American units swept eastward and then turned north, German formations began to realize—too late—that they were no longer maneuvering freely. Roads clogged. Orders conflicted. Units collided with one another in their haste to escape.

Churchill straightened slowly.

“If this holds,” he said quietly, “they are not retreating. They are being gathered.”

The Weight of a Decision Made in Motion

The Falaise Pocket was not planned in a single moment. It emerged from pressure, opportunity, and the refusal of certain commanders to slow down when caution suggested they should.

Patton’s role in that refusal was unmistakable.

While others debated lines and boundaries, Patton saw space closing and pushed harder. His columns raced forward, seizing crossings, cutting roads, denying escape routes. Each mile gained reduced the enemy’s options.

Churchill understood what that meant. He had spent his political life wrestling with decisions made too late, opportunities missed by hesitation.

He turned to his military advisor.

“How many men are caught inside?” Churchill asked.

The reply came carefully. “Estimates suggest close to one hundred thousand, Prime Minister. Perhaps more.”

Churchill exhaled slowly.

“One hundred thousand,” he repeated. “That is not a battle. That is the removal of an army.”

A Moment of Rare Silence

For several minutes, Churchill said nothing. He did not puff his cigar. He did not pace. He simply stared at the map as if listening for something only he could hear.

Those nearby sensed the gravity of the moment. The destruction of such a force would not merely weaken the enemy—it would break the spine of resistance in Western Europe.

Finally, Churchill spoke again, his voice lower now.

“This is the sort of victory that ends arguments.”

An aide asked cautiously, “Arguments, sir?”

Churchill nodded. “About whether this war can still surprise us. About whether boldness still matters.”

He gestured toward Patton’s advancing markers.

“That man does not merely attack positions. He attacks assumptions.”

Churchill’s Private Reflection on Patton

Churchill never fully trusted Patton. He found him volatile, unpredictable, dangerously theatrical. But Churchill also recognized something in him that reminded the Prime Minister of his younger self—a belief that history rewarded those who moved while others deliberated.

In a private conversation later that day, Churchill remarked to a confidant:

“I have known many brave generals. I have known careful ones. But Patton… Patton behaves as if time itself were his enemy.”

The confidant smiled faintly. “And is it not?”

Churchill returned the smile, but it faded quickly.

“Yes,” he said. “But time punishes those who misjudge it.”

At Falaise, Patton appeared to be judging it perfectly.

The Enemy’s Desperation Becomes Clear

As the pocket tightened, reports from intercepted communications painted a grim picture. German units were attempting desperate breakouts. Equipment was abandoned. Command structures frayed under pressure.

Churchill read one summary twice.

“They are trying to escape on foot,” he murmured. “An army reduced to movement without direction.”

He looked up.

“That is what happens,” he said, “when momentum is turned against you.”

The Allied air forces struck relentlessly, further compressing the trapped forces. Ground units closed in from all sides. What had once been an organized front dissolved into fragments of resistance and confusion.

Churchill recognized the significance immediately.

“This,” he said to the room, “is the costliest kind of defeat. Not merely lost ground—but lost coherence.”

A Quiet Statement That Revealed Everything

Late that evening, as the final closure of the pocket seemed imminent, Churchill made a remark that would later be recalled by those present—not for its drama, but for its restraint.

“History will say,” he began slowly, “that many hands closed this trap.”

He paused.

“But it will also say that one hand refused to stop pushing when others feared the pressure might be too great.”

No name was spoken.

None was needed.

The Strategic Earthquake

When confirmation arrived that the encirclement was complete, there was no celebration in the war room. Only acknowledgment.

Churchill sat down heavily, the weight of years visible in his posture.

“One hundred thousand men,” he said softly. “Taken out of the war in one stroke.”

An officer remarked, “It will shorten the campaign, sir.”

Churchill nodded. “Yes. And it will lengthen memories.”

He understood that such moments reshaped not only wars, but reputations. The Falaise Pocket would be studied for decades—not merely as a tactical success, but as a lesson in decisiveness.

Patton’s role would be debated endlessly.

Churchill anticipated that too.

“Some will say he was too aggressive,” Churchill said. “Others will say he did not go far enough.”

He smiled faintly.

“That is always the fate of men who move faster than consensus.”

Churchill’s Final Judgment

In the days that followed, Churchill addressed Parliament with his usual eloquence. He praised Allied cooperation, unity, and resolve. He spoke of courage and sacrifice.

But in private, his thoughts returned often to that tightening circle on the map.

To Patton.

To the speed that turned maneuver into entrapment.

In a letter never intended for publication, Churchill wrote:

“There are moments in war when bold action does not merely win ground—it changes the balance of thought itself. Falaise was such a moment.”

He added one final line:

“We did not merely defeat an enemy there. We convinced him that escape was no longer a strategy.”

The Meaning of Falaise

The trapping of German forces at Falaise did not end the war overnight. But it ended illusions. It shattered the enemy’s ability to regroup meaningfully in the west. It opened the road forward.

Churchill knew this.

As he looked once more at the map, now marked with victories instead of threats, he allowed himself a rare moment of satisfaction.

“Momentum,” he said quietly to no one in particular, “is a terrible thing to waste.”

And somewhere across the Channel, Patton’s army was already moving again—proving that the most dangerous trap of all was not steel or strategy, but time itself.

News

The “Barrel-Less” Tube They Thought Was a Workshop Prank—Until Normandy’s Hedgerows Swallowed a Panzer Push and Thirty Tanks Went Silent in One Long Afternoon

The “Barrel-Less” Tube They Thought Was a Workshop Prank—Until Normandy’s Hedgerows Swallowed a Panzer Push and Thirty Tanks Went Silent…

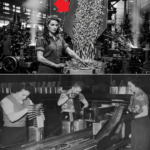

The Factory Girl Who Rewired a War in One Quiet Shift: Her Small Process Fix Tripled Ammunition Output and Kept Entire Offensives From Stalling

The Factory Girl Who Rewired a War in One Quiet Shift: Her Small Process Fix Tripled Ammunition Output and Kept…

The “Toy Gun” They Mocked—Until One Frozen Night It Stopped a Panzer Column, Left a Hundred Wrecks, and Snapped the Offensive in Two

The “Toy Gun” They Mocked—Until One Frozen Night It Stopped a Panzer Column, Left a Hundred Wrecks, and Snapped the…

The Night the “Cheap Little Tube” Changed Everything: How a 19-Year-Old Private Stopped Feeling Like Prey When Armor Finally Had Something to Fear

The Night the “Cheap Little Tube” Changed Everything: How a 19-Year-Old Private Stopped Feeling Like Prey When Armor Finally Had…

Britain’s Two-Million-Ton Ice Carrier That Wasn’t a Ship but a Strategy—Until Science, Secrecy, and the Atlantic’s Cold Math Said No

Britain’s Two-Million-Ton Ice Carrier That Wasn’t a Ship but a Strategy—Until Science, Secrecy, and the Atlantic’s Cold Math Said No…

They Mocked the Slow “Flame Sherman” as a Clumsy Monster—Until One Dawn It Rolled Forward, Breathed Heat, and Collapsed an Entire Island’s Bunker Plan in Minutes

They Mocked the Slow “Flame Sherman” as a Clumsy Monster—Until One Dawn It Rolled Forward, Breathed Heat, and Collapsed an…

End of content

No more pages to load